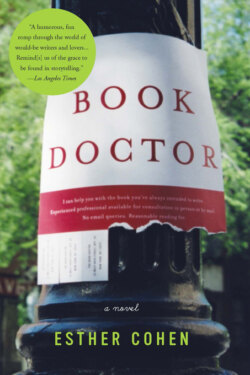

Читать книгу Book Doctor - Esther Cohen - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

earning a living

Arlette Rosen was the kind of person who earned her living many different ways. Typical of her generation, she fell into life rather than carved it out. A feathery, floating, ageless woman, she had danced in a cage, waited on tables in Spain and Morocco, spent summers in Provincetown and Jerusalem and Ixtapa, taught English, and worked in hotels. She’d had more than one boyfriend with an unpronounceable name. Now she earned her living helping people write their books. She edited those they’d already written, or helped them begin books they felt they wanted to write. Sometimes, they just wanted to visit her on occasion, to talk about books they’d write if they had the time.

This incidental career began with a friend of Arlette’s from childhood, a neat woman with small golden earrings, an obvious Alice. Alice had a book at the publishing house where she worked which she didn’t have time to edit herself. She asked for help from Arlette, who was then writing articles on nutritious desserts for pets in a magazine called Rod and Dog.

“Arlette,” Alice said. Her tone was always moderate, considered, fully clear. Unnasal and certain. “You read all the time, I know.” Alice, although she worked in publishing, only read manuscripts. “I wonder,” and here she paused, holding her phone close to her mouth, as though this was a secret, “if you might help me with a fascinating book. The author is well known. It’s a significant subject. Life and Death, more or less. He’s a psychiatrist, with a great deal of recognized insight. What he knows about is the human condition. And more. You won’t be sorry. This isn’t another dull read. That I personally assure you. It’s full of the drama of life,” she added. “And death, of course. Which is really his one true subject. You’ll recognize the name. Harold P. Leventhal. He’s always on TV. Even Imus. And he writes. This is his eighth big book. He just needs help.”

Arlette was suspicious. Why didn’t he write his own book? Was it possible, she wondered, for books not to be written by authors themselves? It seemed odd. Though she could certainly use the money. She liked words, and sentences. She’d edited articles here and there. Alice knew that.

“Fine,” she’d said, “let’s see,” with something like enthusiasm. Alice had the manuscript delivered to her right away. It was called Life and Death: One Prognosis. Arlette suggested they try for something more catchy, but Alice said that metaphors made Dr. Leventhal nervous. They were always too imprecise.

Arlette read Leventhal’s manuscript very slowly. It was that kind of book, ponderous, sincere, full of parentheticals. It was over a thousand pages of life-and-death examples: what life means, what death means, how the two are linked. He used the passive voice, something Leventhal inexplicably liked. Also the word inevitable, which appeared so many times Arlette decided it was his thesis. Life and Death are inevitable. She mentioned this to Alice, who vaguely replied, “That may well be.” Arlette never once thought that this reading, this task, could be the start of a career.

They met, Arlette Rosen and Dr. Harold Leventhal, in a serious room for breakfast, in a large French hotel where Leventhal often ate. He always ordered eggs Florentine. Eleven dollars exactly. Leventhal was tall and dour, the kind of man who seemed miserable and entitled. For both of these qualities, and for his unmitigated seriousness, his detailed and ponderous prose, he had received numerous rewards. Arlette tried to match his seriousness. She told no jokes. He asked no questions. She offered no opinions. He spoke at great length, very slowly. He ate very slowly too, getting his money’s worth out of his eggs. He explained all his books, those he’d finished, those he’d only begun with an eye to the always tenuous future, his particular versions of Life and Death, which he referred to as his principal theme. There were smaller themes for him to plumb as well. He cited, for instance, the relatively important problem of forgiveness. Could it break the cycle of evil? But life and inevitable death were his chosen bailiwick, for now.

She wondered about him, but only a little: He was not the sort of man to inspire much serious consideration. He had no discernible charms, and his physical presence consisted of a very large head, antlike, really, made more so by an overly thin body, fairly long, with a small central bulge above his waist which caused his pants to be far closer to his chest than they might otherwise have been. He wore big, thick glasses that intensified his buggyness, a grasshopper with a PhD. He took them off to make a point, and when he did he blinked continuously.

He was dull, the way people are who study singular subjects for entire lifetimes. They met in early July, and that summer Arlette lived with Harold P. Leventhal’s book. The P was for Prescott. She read the book, early mornings, and late at night. She felt his long sentences, his moreovers and thuses become an ongoing part of her life. Some days she resented it, resented his deliberate ponderousness, his stuffiness and his lack of grace. Some days she was hot, and took the train to the beach, forgetting him altogether.

She began to realize she liked this work, liked the freedom of someone else’s sentences, liked being able to change, in intuitive ways she just knew, small details here and there. And although Leventhal often fought her, generally preferring his own words to hers, she sometimes won, presenting herself as an expert. He believed in expertise, so he didn’t question hers all that much.

She knew she was not an expert in anything more serious than where to buy the best pistachio nuts, or where to find a good Yemenite restaurant in Brooklyn. So it surprised and even pleased her a little that she was comfortable enough with Leventhal’s Life and Death, with trying to find an order that would add up to a book, with revising, culling, editing, moving parts around. In the end, she’d made it clearer, shorter, a little bit better. When the first review appeared, a long, scholarly, pompous review by an English expert on this very same subject, a review full of admiration, even praise, Arlette felt a small yet perceptible glimmer of satisfaction. So when Alice called again, pleased with her work, to ask Arlette to work on a book she deemed even more important, a book about rhesus monkeys, Arlette, without a second thought, said yes. In a year, she’d become a full-fledged book doctor. She even received many queries in the mail. A few each day.

June 13

Dear Arlette Rosen,

Can you help me?

I’d like to write a book called Coping With Disappointment: What to Do After You’ve Finally Found Your True Inner Self. I’m sure there’s a huge market. The self-help audience for this message is infinite.

I am an alternative and inner self professional. My areas of knowledge include Aromatherapy, Bach Flower Remedies, Polarity, Reiki, Alexander Technique, Shiatsu, Reflexology, Homeopathy, Psychic Healing, Feng Shui and Acupuncture.

I need help in the formulation stage. Marge Schaefer, a client of yours (I Can Do Anything and So In Fact Can You) gave me your address.

Yours in hope,

Star Dawn Planet

a/d/b/a/ Olive S. Cooper

To: Arlette Rosen

Jack Vance at Princeton gave me your name. He said you’d remember. Whatever that might mean.

I’d like to send you Black Box, my 32 candid interviews with men and women in the phone sex business. These interviews were conducted by myself. (I am Claeyton Howard, author of Saul

Bellow: A Long, Productive Life, and Philip Roth: Visionary, Misogynist, or Both?). Black Box is a high concept, really. (By the way, if you think White Box might be better, or even just Box, I am relatively open.) One that works.

Black Box is the first book which has a sealed pull-out section (the book will have a male and female edition, red and blue. Also, perhaps, straight, and gay) which can actually bring the reader to orgasm. Guaranteed. I can’t imagine anyone from 12 to 92 who wouldn’t want a copy. It might not become a classic, but the novelty should put it into the Waldo category. Don’t you agree?

Jack Vance suggested your usefulness to me because I am more or less a concept person. The details are how you might be of service. (Who was it who said God was in the details? I believe a famous painter. Perhaps Rubens.)

I’ve got the interviews, and can have them transcribed. But the editing, the order, and that kind of thing I’d like you to do. I’ll pay you, of course. Reasonably well. Are you interested, or at least, somewhat curious? Do say yes.

Claey

HELLO OUT THERE IN ELUSIVE UNKNOWN SPACE.

I have written a deconstructivist novel, called Gone, or Minus. The subtitle will be Quattrocento Beauty. Others have tried. Roland Barthes for one. But you can’t really read him. Mine you can read. It’s as accessible as the shattered (missing) object in cubism, and the atonality of music. It’s a charming, shabby, intimate, accessible, sexual, disconcerting novel about freedom. There are six characters, and they’re all gone by the end. Just gone. (Not dead.) All that’s left is an omniscient frog. It’s not like Beckett, or Pirandello either. Mine are not searching (although they are of course alienated). Also, all six are female, from 18 to 88.

(Where they go doesn’t matter so much as that they leave. It’s a book about leaving, in fact.)

I need some help. There are times the idea becomes too looming. I feel that instinctively. If you could highlight those areas in yellow for me, I would be grateful.

I can pay. I got a grant.

Are you free?

(Not ultimately, but to do this job?)

Fisher Smythe, PhD