Читать книгу Book Doctor - Esther Cohen - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

meetings

Harbinger Singh met Arlette Rosen at three o’clock on a Wednesday afternoon. It was early July, too warm for his dark brown wool suit, but he liked the suit, liked the fact that the color nearly matched his skin. He liked it enough to wear as often as he could. He thought of himself as brownish, but in fact, he was more a deep golden yellow, the yellow of Indian sun. He called it full sun himself, preferring it to full moon. He thought of himself as powered by sun, though profoundly influenced by the moon. Usually, he thought very little about color, his or other peoples. It wasn’t the kind of detail that occupied Harbinger Singh.

He was a man of methods and goals. He made lists, then crossed out the tasks he’d accomplished. He would move undone jobs from one list to another, and sooner or later, the neat equidistant lines indicating completion would cover all his pages. Harbinger saved these pages in a desk in a drawer, numbered by date, and although the entries were barely discernible, and he couldn’t quite remember just what he had done, still the several hundred pages he kept in three black folders gave him deep satisfaction.

On occasion he had an affair, but they never amounted to much. He told himself that these affairs, though even the word was too big, these quick forays into sex, maybe, were a natural part of his marriage to Carla, who wasn’t very interested in sex. While they were still married, he became lightly involved, only twice, with women he’d met through work. Though he’d never thought, even for a minute, that either relationship was love. He loved Carla absolutely. She had work to do, and her work, which put them both into a top tax bracket, took priority over everything else, even pleasure. On occasion, she had something that could possibly be described as an urge, but her urges were not memorable, and her thoughts barely wavered from her job, even then. After sex, she’d often bring up office problems, seeking Harbinger’s advice.

After he and Carla got divorced, he took a few women to dinner, but he found, on those slow and painful evenings, that they had less to say to one another than he and Carla had. Though his relationship with Carla had been more or less flat, and he didn’t know why he should love her, still he did. This love burned through him. He was always there. He thought about Carla day and night, although there was no reason to be so obsessed with a woman so careful, so clean. So rational. She even wore pajamas.

On their last night together, before she moved out, into a big clean building with a doorman and a gigantic parking lot, they had what turned out to be the first of their weekly dinners.

Harbinger asked why she supposed they’d married. Carla, who often spoke as though she were addressing her senior high school class with her valedictory speech, something she had done nearly twenty years before, on the subject of social policy and moral responsibility, replied in a softer tone. “No one knows why they marry. If they say they do, they’re pretending. I suppose we married because we respected one another and our work is somewhat compatible. We were not unhappy,” she added, which was, for Carla, a gentle remark. She would not say more.

“I suppose you’re right,” Harbinger replied. “But what about,” and here he paused, wondering whether the word was appropriate for this particular occasion. Then he just went ahead. “What about love?” he asked. “What about love?” Carla did not seem thrown, or even upset. “A major subject,” she replied. “We don’t know much about it, I guess. No one does. Certainly not us.” She smiled vaguely.

Harbinger imagined he would write this scene very differently. He imagined Carla crying, desperate to be together again. Not cool, but rather enraged. On the edge of her seat with anxiousness. Silently and not so silently pleading Please Take Me Back Harbinger Singh.

“But you loved me once,” he said sadly, as though it were a question. “Of course,” she replied. “Of course I did.”

“Then what changed?” Harbinger asked. He did not want to sound mournful or pitiable, only interested. “What changed between us? And if it’s all the same, why did we both agree so easily to divorce?”

“Nothing’s changed,” she said, and then she added very familiarly, “Harbinger.” She rarely used his name.

“I see,” he said, and then decided that he would rewrite this altogether. They’d both be crying, unable to eat, and they would decide that parting would be a horrible mistake. Then they’d return to their old apartment, warm, dark, full of rugs and Indian music, and make love in a way that surprised them both. Maybe the book should end there.

Harbinger thought of this as he rang Arlette’s buzzer. He wanted the word wild in the title. He read somewhere that it was one of those words, like dogs and whales, that people always liked. Wild End, he thought. Wild Whale, Wild Dog, or even Wild Taxes. Taxes were something he knew well. Even so, he felt wedded to Hot and Dusty. He would ask Arlette Rosen her opinion.

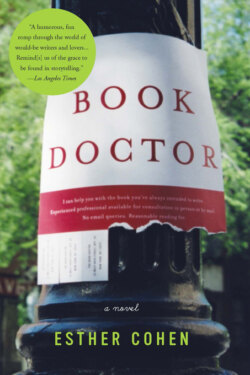

Arlette had dressed for Harbinger Singh. She tried to look officially artistic for her writers, knowing and literary, reasonably in charge, and sure enough of what she was doing. Aspiring writers, she knew, concentrated on these details. She imagined herself a book doctor, and so she often wore white, even in winter. For Harbinger Singh, a lawyer with literary ambitions, Arlette wore a white cotton skirt, plain, nearly Victorian, and a French cotton T-shirt, very simple. She was tall and thinnish, and her face, in the right light, had a handsome cast, like a Russian feminist explorer on a silver coin. But she could look impenetrable too, the kind of woman who’d be too hard to please. She wore earrings, thin silver snakes from Bali that decorated her ears. On her wrist was a silver bracelet, old and foreign looking, surprisingly soft. It moved across her wrist in a light and girlish dance.

Harbinger looked at her and thought to himself, Not Too Bad. Arlette looked at Harbinger and wondered about his suit. She tried not to be as judgmental as she was, but this was an effort.

“Do come in,” she said, and he extended his hand first, to shake.

“Harbinger Singh,” he said unnecessarily, and pumped her hand up and down for a minute. His hand was straightforward and strong.

“Well, hello,” he said again, when she didn’t seem to respond right away.

“Please come in,” she said. “Right in here, if you don’t mind. I only have two rooms. I’ve thought about renting an office for years.” Here her voice trailed off, as though reasons why not were not of their concern right now. “But this is enough,” she added.

He did not look around her living room. He just sat down. The couch was a faded velvet, a pinkish that once might have been more red. The cushions were small satin squares with pieces of embroidery she’d gathered on her trips. She’d sewn them on herself. He did not look at them. She could tell right away that he didn’t care much about visual details. Usually, writers who came just began to talk and Harbinger was no different. Arlette sat across from him in an old rocking chair. She leaned forward with her spiral notebook and a pen.

“I’ve always had the intention of writing,” he said. “A book primarily, although there are other possibilities when that is finished. A play is in my head,” he said. “I call it Queens, referring to one of my homelands. A biography of Gandhi.” Then he added. “And the poems.”

“What about them?”

“There are the poems,” he said, shyly. “I haven’t written them yet. But of course, I am a poet. Aren’t we all? It’s in our souls, I believe.”

“I see,” said Arlette. “And where would you like to begin?”

“With the novel,” he replied. “I just need a little help. A push in the right direction, because I know it is right in my head. The story is there in front of me. I just need time to put it down. And a little help with the process. I am sure.” Here he smiled at her, and crossed his legs, swinging his right foot nervously back and forth arhythmically. Arlette tried not to stare at his moving leg.

“What will your book be about?”

“Well,” he replied, leaning into the cushions on her couch as though he were preparing to tell a very long story. “Well,” he said again. Then he looked at her earnestly, as though she were a client of his, someone with a minor but troubling problem with her taxes. Underpayment, perhaps. Or avoidance for three years. Without the personal resources to rectify her problem right away. Coming to him for advice.

“Well,” he said a third time. “Here I go. I’ve been thinking that I would like to call the book Wild. Wild Taxes, possibly. Although Hot and Dusty has always been in my mind. A year or so ago, when I started conceiving this novel, it was very different. Then I called it At the Bench, or Up to the Bench. Or even just Bench. At first, it was a courtroom novel, which all took place in a small dark room, very formal, presided over by a woman judge from Calcutta,” he said, and smiled. But he paused for a minute, almost lost. Unexpectedly nervous. He recovered quickly, though, and continued. “She had her training in England. Very smart. You can’t put one over on her. Her name, for your information, is May. Un-Indian, that. But we have had many influences. The first book, not actually the first, but last year’s book, we’ll call it for clarity’s sake, was about a murder. A man murdered his wife because she made his life impossible. After her death he found a master plan in her top stocking drawer in the closet. It was to murder him. She had enlisted the support of his mistress, who’d secretly become his wife’s lover. I know this plot is not a first. But I intended to make it different through my choice of particulars.”

Arlette nodded.

Harbinger suddenly seemed very confident. He looked Arlette in the eye, and spoke a little too loudly.

“Now, though, something else has replaced this idea. Now I would like to try something we can call for today just Wild Taxes. Not a murder. A simple love story, of a passionate love that failed. Circumstances wouldn’t allow it to be,” he added, and looked satisfied with his own explanation, as though he’d finally said something he’d wanted to say for years.

“What were those circumstances?” Arlette asked, and wrote the word circumstances under Harbinger’s name. Her authors’ files were only words, jotted here and there.

“If I were to say now, I might lose the impetus to begin,” said Harbinger Singh. “I don’t know that I am able to tell you just like that. There are only two characters, however. Their relationship is set against corruption all around. Incest, murder, death, homelessness, war, the world,” he said vaguely. “Big corporations, the British, others whose motives are less than admirable. You know,” he added, and she nodded. “A difficult world,” he said. Moslems, Christians, Hindus, Jews.” His voice trailed off.

“Yes,” said Arlette. “Very difficult.”

“One of the reasons why I have in mind to write a novel,” he continued, “is that the tax business, while it is lucrative enough, is not very satisfying on a spiritual level. I’m sure you understand this.”

“Yes,” said Arlette. She was trying to keep an open mind. She knew all writers were nervous, particularly in the beginning. Still she felt a twinge of contempt for Harbinger Singh. And taxes. There was something about choosing to do taxes that bothered her.

“I enjoy my work,” he said, as though he knew what she was thinking. “It gives me a chance to see many people. To ask them questions, and hear about their lives. To help them,” he said, then added, “even somewhat. I have no illusions on that score.” He looked at her and smiled, as though she were the client, not him.

She liked him a little better.

“And you?” inquired Harbinger. “And you?” he repeated. “When I meet new people, I often explain myself, to put them at ease. Perhaps we can do the same. Let’s begin with your process, and your fees. I am interested in both. I can describe more of my character if that will help you. I collect takeout menus. One of my few idiosyncrasies. I enjoy them. They are peculiar artifacts of Americana. In fact, if I were an archaeologist, they would be my typology. They are numbers and words in lines, so they fulfill other needs of mine as well.”

“Well,” she said, not knowing what to say about his menus. “My fees, first of all, are yours. I receive what you get per hour. In your case, I assume that’s about one hundred dollars, more or less. But you’ll have to tell me.”

He looked annoyed. “But you have no overhead,” he said. “No secretarial help, for example. No equipment. No expenses except for your pen,” and here he smiled. “I don’t even see a fax machine. Not that you need it of course. I am making no judgments, I can assure you of that. I myself am a technical caveman. Or is it cave person? Do forgive me.”

“I am providing a service that is hard to evaluate financially,” she said. “I’m sure people have this problem all the time with their taxes. What is a novel worth? One dollar? One million dollars? Somewhere in between? What is it worth for you to write your novel? Fifty dollars? Three thousand ? I’m afraid the way I resolve this question for myself and for my clients is to suggest that my work is equivalent in value to theirs.” Arlette stood up, moving around the room like a teacher in a classroom. She felt unsettled, and yet she’d said these same words many times. “I don’t think, of course, that money and art are connected. A wonderful poem, for instance, is worth millions. But a bad poem’s not worth nothing. I want to make it possible for everyone to work in this way if they want. If you don’t find the process acceptable, of course I understand. Perhaps you can find someone cheaper,” she added. “As for how I work, that depends completely on you. I give you exercises to help you think about your characters. To make them real. But you’re the one who tells the story. I help you do that,” she added. “When we’re through, you’ll have written enough to make you comfortable with the process,” she said. “You’ll have a better idea what you’re doing once you start.”

“I’d like some time to consider this,” he said. “The finances add another dimension to the equation. I thought it would be cheaper. Not that I am disparaging your services. Not at all. But I will think carefully, and call you in a few days. In any case, I will be happy to pay you for this initial consultation,” he said. “Please,” he smiled, and stood up, removing his wallet tentatively. It was old brown leather, well used. He opened it toward her, to display very neat bills, a large enough stack. She imagined them organized by serial number.

“No,” she said. “Our first meeting is free. Everyone is entitled to one free session in all service industries. Don’t you agree?”

“Not entirely,” he said. “That might put many out of business. Just one question, by the way. Will I be able to make enough from the sale of my novel to cover your expenses?” His question seemed innocent.

“This is about writing,” she said. “Only writing. But you’re not the first one to ask me that question. There’s a poet I like very much, named Edward Field, who wrote a poem called “Writing for Money.” I learned it years ago. It goes like this:

My friend and I have decided to write for money, he stories, I poems. We are going to sell them to magazines and when the cash rolls in he will choose clothes for me that make me stylish and buy himself a tooth where one fell out. Perhaps we will travel, to Tahiti maybe. Anyway we’ll get an apartment with an inside toilet and give up our typing jobs. That’s why I’m writing this poem, to sell for money.

“I can give you a copy, if you like,” she said.

“Oh no, that won’t be necessary,” he said. “Perhaps later on I may have the need for a copy. But not right now. Please don’t stand,” he said. “I am capable of going without undue fanfare. But thank you,” he said. “I feel optimistic.”

Then he left. She wasn’t sure if she’d hear from him again. She waited a few minutes, until he was clearly gone, to pick up her mail from downstairs. She thought about him, but very, very briefly. A small moment.

There was only one letter, in a brown recycled envelope. She often wondered if recycled envelopes had been envelopes before. The handwriting was cheerful, circular, a little too young.

Hi Arlette,

I don’t know if you remember me, but I remember you! We were on the same dorm floor. Different ends of the hall. I had brown hair and was very slightly overweight. My room was 315.

I got your address (obviously) from Susan Davis. She told me you’re a book doctor. What an unusual job. I’m sure you meet a lot of fascinating people.

By now, you’re probably wondering why I’m writing. Well you’ll never believe this. I was a sociology major, so I’ll bet this seems unlikely, but I wrote a novel. It’s based on a true story. I don’t feel I can do it justice with a plot summary. (Remember those from book report days? I read in my How to Query Handbook that people still want them. Can you believe it?) But maybe helping with plot summaries is one of the things you do. The working title is Go Figure, and it’s the story of my life. (It sounds like it could be a book about keeping track of your money I guess. But it isn’t.) Speaking of money, I really don’t have any idea what a book doctor costs. Do you charge like a medical specialist? My ex was an ENT doctor. Can you give me an estimate? Or do you have to see the patient first. Ha Ha. Should I just send it to you?

Yours for the lavender and white!

Debbie Altman

Harbinger Singh quickly replaced Debbie Altman in Arlette’s mind. Though she wasn’t sure why.