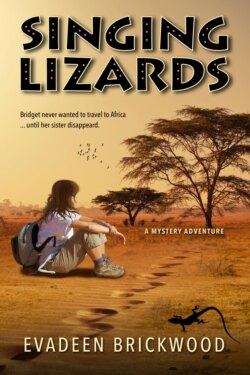

Читать книгу Singing Lizards - Evadeen Brickwood - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1

ОглавлениеWhy did I have to think now about Botswana? It had taken only a brief look at my steaming Johannesburg garden through the big window in the study. The tall avocado tree and pink protea bushes were still glistening from the rainstorm the night before. I tried to concentrate on my work: the translation of an urgent divorce decree.

The phone rang. “Hello.”

“Can I speak to Bokkie please?”

“Um, there is no Bokkie here.”

“But this is Bokkie’s number.”

“I’m afraid not. You must have dialled the wrong number.”

“Oh – sorry.”

“No prob — ” The man had already hung up.

I had known a Bokkie in Botswana once… an unpleasant character. There it was again. The thought of Botswana, creeping up on me.

I didn’t even know that this remote African country Botswana existed, before my sister Claire decided to work there. To be honest, I found the mere thought of Africa somewhat unnerving. Southern Africa, with its vast areas of dry and thirsty desert seemed especially intimidating. Claire didn’t mind all that. In fact, it was exactly what she wanted. Then she went missing in Africa on 16 July 1988.

M i s s i n g - such an ugly word. Oh, how much I had missed Claire! I must have been temporarily insane. Why else would I have just upped and left England so suddenly for Africa? It had taken all my courage, but I needed to find Claire, needed to see for myself what had happened.

At first I found the silence there unsettling. I was still reverberating with a western rhythm, an inner buzzing, and it took me a while to learn how to listen to the quiet…

The phone rang again. Why do people always call when you don’t feel like talking?

“Hello?”

“Can I speak with Bokkie?”

“Wrong number.”

This time it was I, who hung up. I sat down at my desk by the window and looked out into the garden. Just outside the window, a yellow weaver bird was busy stripping a palm leaf to build his nest on the tip of a bouncing branch. My thoughts wandered.

It had taken her new employer two weeks to inform us. Two long weeks! They thought she might have taken a few extra days on her short trip to the Okavango Delta. Apparently it was quite normal to be late in Africa. I didn’t know back then that time passes more slowly in a country like Botswana.

A couple of days here and there – what’s the big deal? ‘African time’ they called it. More time passed until the police in Botswana got involved. Then Scotland Yard. Would it have made any difference - the time?

Remembering the year before Botswana was bittersweet. We called each other Foompy. Even at the age of 22. I suppose that’s one of those strange things twins do when they are in their own secret world.

I am Bridget, the older one of us, by two whole minutes. We both have the same blue-green eyes, but Claire is blonde and petite (Mom’s ‘mini-me’) and I am the taller brunette, who takes after Dad’s side of the family. My face is rounder and I have an English rose-and-cream complexion. We were walking opposites really, and Claire was way ahead of me.

She always smiled and was popular. I was serious and shy.

Boys flocked around her and Claire took it in her stride. She usually had a steady boyfriend anyway. I was more of a wall flower, had my small circle of girlfriends and lukewarm affairs with boys.

She wanted to travel. California, Denmark and Peru. We had just been to Peru with our friend Liz. For an entire three weeks! I was done with travelling for a while after that, but Claire wanted more.

I was content with my life in England and knew every nook and cranny of our small town, away from the hustle and bustle of big city life. I loved everything about Cambridge. Its moss-covered roofs and the medieval feel. The carols by candlelight at King’s College, the punters in their boats below the bridges; why would I want to live anywhere else? The world was a big and scary place. Filled with things I didn’t understand.

I had my work as a freelance translator and Claire was a technical draughts person. After the trip to Peru, she was seriously planning to leave Cambridge on a 2-year contract with an international engineering firm in Gaborone, Botswana. Botswana was in the Southern tip of Africa!

There would be an ocean and a huge continent between us. I couldn’t even imagine it. And anyway — what about me?

It had all been Pierre Boucher’s fault! If it hadn’t been for his glowing stories about Southern Africa, she would never have wanted to go and live there. Claire had met Pierre Boucher years ago at college in London. He and his Tswana girlfriend had married and settled in Botswana. Claire had met up with them again in London just recently. That’s when Pierre told her about the big house in Francistown with its swimming pool, maid and gardener and all the trimmings. Not to mention the incredible landscapes and the peaceful quiet around them.

All of a sudden, Claire had to see this fabulous country, wanted to enjoy the easy-going lifestyle, the freedom, the endless savannahs, the wildlife, the huge sky.

She had gone all the way and applied with an agency for a job in Botswana — and was accepted immediately.

A dream come true for her - a nightmare for me.

Nothing worked, not complaining, not being reproachful, not pronouncing threats. Nothing could sway Claire’s decision. Then I tried bravely to support her. As much as I suffered and as much as we argued, I didn’t stand for anybody else criticising my sister. Most people knew that.

David obviously didn’t. My boyfriend David and I actually quarrelled about it in our favourite pub on Norfolk Street. We practically never discussed feelings, but my nerves were in a raw state and truth be told, things weren’t so brilliant between us anymore. He didn’t approve of my sister dragging me halfway across the world. ‘What’s wrong with the Midlands or good old Cornwall?’ he had wanted to know just the other day. As if life was that simple.

We were savouring our usual pasta while comparing cricket teams, when he hit me with his observation.

“Your sister’s odd. Why does she want to live in Africa of all places? I could never live in Africa! Idiotic.” What? I nearly choked on my tagliatelle Alfredo.

“Oh really, and why is that so idiotic?” I glowered.

He took a swig from his beer bottle. Grolsch was his favourite.

“Everybody knows that. It’s not safe there. Africans get drunk a lot and all that...” David saw my expression and groped for an explanation to make his point.

It didn’t occur to him that he himself was on his second beer in half an hour.

“…and they start a war at the drop of a hat. There is so much dangerous jungle and it’s dirty and way too hot… and so uncivilized,” he quickly concluded his brilliant argument. David took another fortifying swig from the beer bottle and sat quietly.

A group of students had just walked in, looking for a free table. A couple of girls stared as if to say ‘get up and go, it’s our turn now’. This irritated me even more.

“So, everybody knows that about Africa! Really? Since when are you so prejudiced? We are talking Botswana, that’s by South Africa, you know, not on Mars. Miles from Angola and Eritrea. There’s no war there and no dangerous jungle.” At least as far as I was aware.

“I knew that,” David stammered. “But still…South Africa isn’t exactly safe either. With apartheid and all that.”

Bull’s eye! In the year 1988, South Africa was still in the middle of its struggle for freedom. I also thought it was too dangerous, but Claire couldn’t care less.

“You know what, David? You are odd!” I flew at him to cover up my fear. “Flip! Claire’s just following her dream and she is lucky enough to have a boyfriend, who wants to go with her. I wonder if you would do the same for me. Probably not!”

That wasn’t fair, but I was cross with David and I was cross with Claire. Why did she have to go to such a dangerous place?

David had just blabbered away without thinking, insensitive as ever. What did he know anyway about other countries? England was his world. But Claire had forced me to think beyond England, even about Africa. Like it or not.

Claire’s boyfriend of eighteen months was Tony Stratton. Nice guy, actually. An economics and maths teacher, who had found himself a job at a private school in Gaborone straight away. Would she have gone without him? Definitely.

David scanned the pub nervously and kept pushing back his thick brown hair. I could guess that he was embarrassed by the scene I made. Were people staring at us? Where were his friends already?

“I didn’t see that one coming!” David laughed and acted as if I had made a big joke. “Oh come on Bridge, what’s wrong with it? I like being in England. Africa is too…too different. A holiday maybe. Although that’s pushing it a bit. I’d prefer Mallorca. But moving to Africa — I just can’t understand that.” He shook himself.

“You can’t let it go now, can you? Oh, you just don’t understand anything at all,” I cried. I couldn’t take any more of this. I felt the fleeting urge to shake David, but instead I made up some excuse about a head ache. I had to deal with all those feelings welling up inside me.

All I could do was to take my purse out and pay for the Tagliatelle Alfredo. And in any case, such a show of passion would have rocked David’s world even more. We weren’t exactly what you would call passionate.

I needed to walk home by myself, needed time to myself. The thought of the comfortable home in Tenison Avenue made me walk faster. Here I felt safe. Just big enough for our family of four, Mom, Dad, Claire and me.

In summer, red holly hocks and blue forget-me-nots framed the soft green lawn at the back of the house. Here we came together to talk and relax on white garden chairs, having tea, while Hinny, our wily grey cat, watched us from the top floor balcony.

I turned into Sturton Street, then into Tenison Avenue. Even in the dark, the warmth of our house pulled me closer. My anger blew itself out quickly, but thoughts I had so successfully evaded, popped into my head. I was forced to face things for what they were.

Claire was leaving me behind and it hurt. Badly. My twin moved to Africa and I was stuck in a rut with David. Movies on Wednesdays, pub dinners on Thursdays, sport on Fridays. Same old same old, while Claire launched into the unknown. I hadn’t really thought of it that way before. Claire was the spice of my life.

Was I being selfish? I decided that I would visit Claire soon, and stepped out more forcefully. Perhaps I should have a good chat with her, I thought as I opened the front door. But Claire was not at home.

The next few days, Dad answered the phone. I was too chicken to speak to David. We wouldn’t speak about feelings anyway. Then David stopped calling. The breakup was quick and painless. My feelings about Claire, however, were so much more painful.

“Don’t leave me here all alone,” I begged her. “I don’t want you to go.”

Oh, I knew how pathetic I sounded.

“That’s not fair, Foompy. And anyways…you are not alone.” She spoke to me as if I were a child. “There’s Mom and Dad and David…and Zaheeda, Liz and Diane…and you do like it here, don’t you?”

Not without you I don’t, not without you! I didn’t dare say it. Claire sat in her wicker chair leaning against the wall. The dappled shade outside the window was throwing patterns on the David Bowie poster behind her. I hadn’t told Claire yet about my breakup with my David. It didn’t really matter right now.

“What if something happens to you?” I grumbled and rolled over on the quilted bed cover, lying on my tummy, chin in both hands.

“What’s supposed to happen to me? I’ll live in a company house with lots of colleagues around. Probably won’t ever have time to myself. And then there is Tony, of course. He’ll look after me,” Claire tried to calm me, while she drew doodles on an empty envelope.

She seemed far away. Probably somewhere with Tony. The thought made me feel jealous for half a second. There had been brief talk of marriage, but as far as I could tell, there was no clanging of wedding bells yet.

“Won’t you miss me at all, then?” I sulked.

“Of course I will! You’ll come and visit me in Gaborone as soon as you can, right?” Claire tried to sound excited for me.” Then we go and explore the Kalahari together.”

“Yes sure, fine,” I said casually, more to annoy her than anything else.

“Oh don’t be so cross, Foompy.” She made a funny face and I had to laugh.

But Claire had been wrong! A few weeks later, my world had turned on itself. Something did happen to her — Claire had disappeared.

When the news broke, I was numb with sadness and worry. Nothing made sense anymore. It couldn’t be true, just couldn’t! I crept upstairs to Claire’s room, threw myself on her bed, buried my face in the pillow and screamed. Until I didn’t have a voice left to scream. Then came the tears.

I shouldn’t have let her go, I kept thinking, I should have stopped her somehow. The needle-sharp thought poked out any kind of logic. As if it was possible to stop my stubborn sister from doing anything. But what was I supposed to do now?

The news exploded in our town. Newspapers were full of articles about Claire and her mysterious disappearance. Was it murder or abduction? Opinions chased each other. What’d you expect? Africa was a dangerous place. I felt nauseous every time I saw the headlines and stopped buying newspapers. A week later, sports news had replaced Claire’s story.

Her old red Mazda was found abandoned in a field somewhere close to Mochudi. The name Mochudi meant nothing to me then. The police interrogated the locals, but they hadn’t seen or heard anything. Of course not! Fingerprints were inconclusive, because children had played in the car.

Even a British MI 5 Special Unit, doing some training in Botswana at the time, had allegedly found nothing useful to speak of. We were to assume the worst!

Claire had travelled alone — and why not? Tony had to mark exam papers and couldn’t come with her at the time. How could he have known what would happen? But I blamed him in the beginning, for a minute or so. She was planning to visit Pierre and Karabo in Francistown, her last stop before Gaborone was the Tuli Block, a remote national park. She had booked herself into a lodge to see the elephants. She never arrived there.

We waited for Tony to call, but Tony didn’t call. Maybe he didn’t have our number. I sent him a letter. I waited for his answer. And waited. I guess I began to think right there right then that I should take things into my own hands. I couldn’t bear all this waiting.

The ‘International Missing Persons Bureau’ got involved. My father asked the authorities, if he shouldn’t help them by going to Botswana. The answer was a resounding ‘No’.

Everything humanly possible was being done already. Family presence would only hamper the investigation. Unbelievable! I was furious. Why didn’t they do their job properly then? You couldn’t tell me that there was no trace of Claire to be found anywhere with all this investigating going on. And to tell us to assume the worst and sit around and wait!

Then the nightmares started. Blurred images of Claire behind a misty veil. Laughing, saying something I couldn’t understand... then fading away back into the mist. I wanted to call out to her, grab her, and woke up with tears running down my face every time.

But there was hope. She had to be alive, I could feel it! Just where was she?

I didn’t tell anybody about my dreams. The atmosphere at home had become unbearable and the house in Tenison Avenue had lost its warmth for me. Mom cried all the time and Grandpa had come up from London to console her. Dad was withdrawn and mostly sitting in his study. I wasn’t so sure that their ideal marriage would survive the pain of their loss.

Dad was a handsome, brooding engineer from Germany. He had followed my mother to England, after they had met in their twenties on a train in France. It must have been awfully romantic and was probably the most courageous thing he had ever done in his life.

Mom lectured history of art and Dad had retired just before ‘the thing’ with Claire happened. Their life had been picture book perfect. Until now. I felt powerless.

After a while I had no more tears. I felt just helpless and angry. At everybody. It seemed as if they had just given up. The lot of them! Didn’t they know she was still alive?

I saw Dad in the kitchen and I tried to talk to him.

“We have to do something,” I began carefully.

“Do something?”

“Perhaps you should just go there…”

“To Botswana? What am I supposed to do there? Mom needs me here and the police are already doing their job,” my Dad flared up. Only to apologize seconds later. “Sorry darling, I didn’t mean to be so gruff, but my nerves...”

I could have yelled at him: the police are doing their job? Really?! Fix it, Dad, why don’t you fix it? But I couldn’t say another word. It hurt too much to speak about Claire.

Mom took tranquilizers and wanted to speak only with her therapist. I had the inexplicable feeling that she made me somehow responsible for everything. The idea of going to Botswana and finding Claire myself, began to take shape.

When the dust had settled and articles about the vanishing had disappeared for good, I met with my friends for tea. Our doe-eyed friend Zaheeda was at her sister’s wedding in Manchester that day. I wondered whether she would have understood; why I needed to go to Africa to find Claire and all.

“Oh Bridge, what do you want to do there - in Botswana?”

Liz pronounced the word as if it was a disgusting insect.

“I knew something was going to happen when Claire went away.” Her pointy nose trembled.

“Oh bloody hell, Liz, how can you say something like that in front of Bridget?” scolded Diane with unusual vehemence, “You didn’t know that. Nobody could have known. Claire has always travelled and knows the ways of the world.”

Everybody stared at her. Diane was usually soft and gentle.

Liz didn’t let up. “I guess, but that didn’t help her now did it? Why couldn’t Claire have moved to Italy or Spain? Or even America? At least she would have been in a civilized country.” She didn’t mince her words.

She meant well in her own way.

“Sometimes I think that it was fate. I mean that Claire went to Botswana and that I must go and find her there.” I knew it didn’t make much sense, but I was still searching for a logical explanation.

“Oh Bridge, of course you would think that…” Diane said soothingly, as if I was a fragile mental patient.

They both looked at me in a commiserating sort of way, as if I was about to fall completely off the rocker.

“Oh stop staring at me like that! Claire needs me. She’s still somewhere out there and she is all right. I can feel it.”

“Sure you can, love…” Liz quickly changed the subject. “What about David? Haven’t seen you two together for a while.”

“Because we broke up, I think.”

“You think?” cried Liz. She had played matchmaker for us after all.

I just shrugged my shoulders.

“We had a fight beginning of May and haven’t spoken since.”

“Really?” Liz couldn’t believe her ears.

“Yes, really.”

“Well, that didn’t last very long. Was it the whole of two months?” Liz hinted at my usually rather brief relationships.

“Three months. He doesn’t even know that I’m going to Botswana. Unless somebody told him.”

“You haven’t told him!”

“No, what for?”

“Want to talk about it – about David, I mean?” Diane looked sad on my behalf.

“Not really, but I guess I should give him a ring later. To clear things up.” Why not?

“Good idea…”

“More tea anyone?” Diane asked softly.

I left soon afterwards and felt misunderstood.

That afternoon David and I had a heart-to-heart at ‘Jesus Green’ to talk things through. The park was full of people soaking up the sun. I told him about Claire’s disappearance. He gave me a brief I-told-you-so look. Sigh.

“So I don’t count anymore then?” He threw a flat pebble into the lake. The pebble skipped a few times across the water surface before disappearing.

“David, please understand. It’s not about you.”

“I thought we could give it another go.”

“What for?” Didn’t he notice how lukewarm our feelings had become? Skip, skip, skip. Another pebble travelled across the water and sank.

“Don’t I deserve another chance?”

“David, I think we’re wasting our time with each other.”

“Gee, thanks a lot.” He squeezed his eyes together and watched the pebble skip.

“I didn’t mean it that way.”

“Sure you did.”

We squabbled a while in this pointless, repetitive way of so many couples, who don’t fit together. In the end we at least agreed to disagree. There was nothing more to be said.

It must have been before the launch at Heffer’s book shop when Tony’s rather short letter arrived. Oh, why didn’t we have e-mails back then? He blamed himself for letting Claire go by herself, for thinking that she would be safe. I had skipped past that point long ago. He asked me to give him a call at the hotel in Palapye, the village where he had found another teaching job. How did one pronounce that? Palapye.

Tony didn’t have a phone at home and had booked a time slot for 7:00 p.m. on Friday. One had to pre-book a phone call! Apparently, nobody in Palapye had their own telephone. Luckily the letter had arrived before Friday. I couldn’t wait to speak to him. Tony would surely understand.

We spoke on Friday as planned and then I went to Heffer’s bookshop. To the launch of the novel ‘Talk to the Wind’ by Frederick Humphrey. My parents were already there. Frederick Humphrey was a famous novelist — and he was my Grandpa.

The blurb on the back cover promised: ‘A tantalizing crime thriller set in the colonial Kenya of the 1920s. Fear holds sway among the decadent expatriate society of Nairobi...’

This was usually all I read of Grandpa’s books. The back cover. What if I didn’t like the book and he asked my opinion? I didn’t want to hurt his feelings.

Grandpa smiled at me in the picture. He had classical features and a full head of grey hair, good-looking for 72, and right now he was sitting inside signing books.

“I’m going to find Claire in Botswana,” I announced to my parents at last, holding a glass with white wine, as we stood outside on the sidewalk. Music and laughter came from inside the shop.

“You are what?” My father was flabbergasted. I noticed how grey he was getting. “Have you gone daft?”

“I’m going to Botswana,” I repeated stubbornly and endured the pained stares. I had no choice; I had to talk to them.

“No you’re not.” Dad’s German accent always became a bit stronger when he was upset. A lonely truck rattled past us over the cobblestones. Fred’s Office Furniture.

Mom had tears in her eyes again.

“You can’t just leave us now,” she pleaded, shaking so hard that she spilled some of her white wine.

“I’m so sorry Mom. I don’t want to hurt you, but Claire is out there alone. I need to find her and I can’t do it from here,” I said firmly. “I cannot wait any longer. I just have to do something now!”

My heart sank at the mere idea of going away, but my parents didn’t have to know that. I could see Grandpa through the large shop window, chatting to adoring fans.

“Why not let the police handle it? They told us that we would be in the way… and what if something happens to you as well?” my father demanded to know. I had asked Claire pretty much the same thing.

Claire had to calm me down. Now it was my turn to calm my parents. Another car rattled past the bookshop, grinding on my nerves.

“Nothing is going to happen to me, I promise,” I insisted. “I’ve already spoken to Tony, and he said that I can stay with him at this place in Palapye for a while.”

Palapye. Paalápeea. The foreign word prickled on my tongue.

“We’ll manage to find Claire together.”

Tony hadn’t exactly said that; just that he would help me wherever he could. Whatever that meant. His surprise had carried across the shaky phone line, when I invited myself. But right now, I couldn’t talk to my parents about any doubts I might have. I needed my parents’ blessing.

“Oh child…” Mom’s eyes had a pinkish hue, but struggling for words, she bravely held back the tears. And it was my fault. I felt a tickle in my throat and had to cough a little. I hated breaking her heart even more, now that she seemed on the mend.

“I don’t like that idea at all.” Dad looked unhappy, his face crestfallen. “Not at all.”

“I’m not doing this to hurt you, but Claire is my other half and I just can’t wait anymore. I have to go there. To Africa,” I declared in desperation, close to losing my courage.

We didn’t speak for a few painful moments. Grandpa saw me through the shop window and waved, smiling. I waved back.

“If this is what you have to do child…” Mom sobbed and wiped away a tear. She looked at my father. “Mike...” He stared crossly at a carved wooden gate across the street. Were they relenting? I closed my eyes.

“We cannot keep you here, Bridget,” he began and I stared at him, “if you must go… but you will report back regularly and…” Dad took a deep breath and gave me a list of rules that grew longer during the next couple of days, although he knew that I would ignore most of them. I was 22 after all.

My parents were still free spirits after all! I knew right then that they would be okay.

Mom reluctantly promised to pass messages on to my most important clients. That I would be working overseas for a while and to please contact Diane Langer so long. The night before I left, I overheard Grandpa and my parents talk.

“What about the civil war in South Africa?” my father demanded to know. I held my breath.

“Please lower your voice, Mike,” Mom said alarmed. “She might hear you.”

“I can get in touch with the High Commission in Gaborone, if you want. They’ll keep an eye on her, to be sure.” That was Grandpa.

I knew he had still connections in Africa.

“It’s in the news all the time. Bombs are going off in shops and nightclubs and Botswana is right next door. What if Bridget is caught in a running gun battle?”

“Oh Mike, we talked to Claire about that and it didn’t make any difference,” Mom sniffled.

“Look, the last bomb blast in Gaborone was two years ago and I’ve never heard of running gun battles. The military is on the alert,” Grandpa declared. “In any case, things are changing fast in South Africa. You’ll worry yourself silly with all this talk about bombs.”

There was a brief silence, then I heard sobbing noises. “My babies!”

“There, there Sarah, it’ll be all right. You never know, Bridget might just find our Claire and bring her back home.” Had my Dad really said that?

“You never know,” Grandpa agreed.

Shuffling sounds. All three of them went into the lounge.

I cried a little and felt guilty. Then I pulled myself together and folded my last t-shirt. My trusted duffle bag that had followed me around Machu Picchu and Los Angeles was popping at the seams.

The following day I kissed my parents goodbye and went with Grandpa to London. I left my comfortable Cambridge life behind to find my sister.

The formalities in London would take at least a couple of weeks to apply for visas, get inoculated at the Institute for Tropical Diseases and all that. Two weeks to pluck up my courage. Two weeks – all of a sudden it sounded so very short.

Soon I was sitting in the stylish flat Grandpa owned in Arlington Road in Camden. I stared at the list of prescribed vaccinations. My heart sank. Cholera, typhoid, yellow fever, immunoglobulin. What on earth was immunoglobulin? According to the pamphlet, it had something to do with hepatitis. Surely necessary, but were all these injections on the list necessary? I hated needles. Would I drop dead immediately, if I didn’t have all of them? No, I had no choice; it was part of the travel requirements.

The wind changed its direction and gentle rain splattered against the windows. Down in the towel-sized back garden, the spiky tops of slender cordyline palms waved forth and back. It was puzzling that the London climate was mild enough for exotic plants.

The enormity of my plan hit me. What if my mission failed? What then? Why did it have to be such an unhealthy country that required a battery of vaccinations? No need to panic – breathe in, breathe out...

I leaned back on the leather couch and stared accusingly at the painting on the opposite wall. An African landscape in a broad golden frame of all things. It was beautiful, with baobab trees against an azure sky, a herd of elephants in the distance and a leopard stalking grazing gazelles.

“Does that mean that I must get those awful injections?” I questioned the painting. The African landscape didn’t answer. On closer inspection, the elephants seemed to be moving a fraction. On the left, the leopard had appeared fully between the undergrowth. Was it moving closer towards the gazelles?

“You know what, picture? Let’s just get it over and done with. Enough with the stupid self pity.” Bridget you’re going bonkers, I scolded myself, pull yourself together already, you are talking to a picture!

The last time we were in London, Claire and I had come to see David Bowie in concert. My heart ached at the thought. Claire and I. By the end of the concert, she had danced with others on the stage, but as usual, I was too shy to do something like that. It had even been exciting to ride on the tube and shopping up a storm in Oxford Road with its little boutiques.

I took out Claire’s letters. There were five of them. She had written one of them every week on thin, blue airmail paper. The last link between us. She had written about the landscape, the weather, her colleagues, her job and that she was excited about seeing the Okavango Delta even if it was just for a few days.

I tried to imagine Africa. Vibrant colours, teeming markets and laughing people. Drumbeat and dancing in the streets. Restaurants serving tantalizing food made from coconuts and freshly-caught fish in odd-shaped calabash dishes. Hot humid air, pith helmets, lions and elephants, waterfalls and…Tarzan swinging on a liana. Stupid cliché, I know, but that’s how I imagined Africa. I knew zilch about witchdoctors, tokoloshes and the world of the ancestors…

I found almost all the episodes of a South African TV series in the dingy video shop on the corner. It was about Shaka Zulu, the great and cruel warrior chief of the Zulu people in the 19th century. Not exactly modern, but it would do for starters. Soon I could sing along to the opening tune. “Bayete, kosi, bayete, kosi…we are growing, growing high and higher…”

I don’t know if Shaka Zulu had anything to do with it, but I began to notice 'Africaness' around me. Clothes and baskets in shop windows; drumbeat coming from a flat. Dark-skinned people in the street or in the tube seemed to smile at me more often. Perhaps they sensed that I was going to visit their mysterious continent soon. Perhaps they were just 4th generation Brits from Hackney with a Cockney accent.

Claire would have made fun of me. Claire…

During the two weeks in London, I waited for news from Botswana. Once I imagined that Claire had been found in some village in the Tuli Block and was now sitting in a nice lady’s farm kitchen, sipping hot cocoa.

‘I must tell you all about it, Foompy,’ she would say on the phone with a smile in her voice. ‘You won’t believe what happened to me.’ I could hear a chuckle in her voice.

I was in a constant state of nervous tension, like a tightened spring. No wonder then that I started speaking to paintings and such things.

When it was time to get the vaccinations, I took the C2 bus to Great Portland Street and then the tube to the Institute for Tropical Diseases in Bloomsbury. The needles were just as horrid as I had imagined. I suffered for a few days with a fever and a swollen arm. At least it distracted me from my sadness for a while.

I hadn’t seen much of Grandpa. Then one evening, a few days before my flight, he must have felt the urge to cook. When I came home from the video shop, a simple meal stood on the posh beech-wood table. I choked back some tears. Classical music played in the background. Claire de Lune by Debussy.

“Hi Grandpa!”

“Hi poppet, feeling hungry?”

“Sure, that looks good.”

“Sit down, help yourself. There is salad in that bowl.”

“Did you have to get vaccinated when you went to live in Kenya, Grandpa?” I asked, while sucking green pesto spaghetti through my teeth.

Grandpa had lived much overseas as a fledgling journalist. I guess that’s where Claire had inherited her adventurous streak.

“To be honest, I don’t remember exactly, but I’m sure I had to get some injection or other. How is your arm doing?” He pointed with his chin to my left upper arm. It was still a bit swollen.

“Getting better, the fever is down, painkillers seem to be working.” I rolled green spaghetti onto the fancy silver fork.

“Did you speak to your mother today?” Grandpa asked me.

“Yes, this morning. She’d like me to think about the whole trip again,” I sighed.

“I see, but you have made up your mind?” Was there an undertone. If Grandpa didn’t want me to go to Botswana, he had yet to say something to that effect.

“Of course! I would never get so many injections and then not go to Africa,” I replied. “Mom said they’ll come to see me off next weekend. Well, to say goodbye. She has to be back in Cambridge on Monday morning.”

“Pity. But I’m glad they are coming, even if they can’t see you off on Tuesday.”

“Mhm,” I uttered in consent and swallowed quickly. There would be a lot of tears.

“I must just phone about the visas tomorrow morning.”

“Splendid. Then you’re all set.”

“Grandpa, what is it like – in Africa? Is it as dangerous as people say?” I asked impulsively. “Somebody even said to me the other day that I must be mad to go into a country like Botswana.”

“Who says things like that?” Grandpa looked up in surprise.

“Some businessman I met at the Institute of Tropical Diseases. We sat next to each other in the waiting room. He said they only have witchdoctors there, but he couldn’t tell me what exactly witchdoctors are.”

“People should mind their own damn business,” Grandpa growled. “Of course they do have hospitals and proper doctors. Don’t be silly. He’s probably never been anywhere near Botswana.”

“No, I guess not. He said he always flies to South America.”

“To many Europeans, Africa is nothing more than one big blob of jungle. A single country and not a continent with many different cultures. ‘African’ covers just about everything: appearance, food, clothes... But Africa is as diverse as Europe. Kenya is completely different from Togo or Sudan or Botswana. Even Zimbabwe and Namibia are different, although they are right next door to Botswana.”

Guilty as charged! I was one of those ignorant Europeans, but I was too ashamed to admit it. So, Zimbabwe and Namibia were next-door neighbours to Botswana? Maybe I should pay the library a visit tomorrow. Watching episodes of ‘Shaka Zulu’ was obviously not enough preparation for my trip.

On the weekend, my parents arrived in London in a last-ditch attempt to persuade me not leave for Africa.

“Love, what if you need help and have nobody to turn to?” Dad argued. We were standing at Victoria Station, waiting for the bus to Cambridge.

“Or you could get sick.”

“I’ve had all the injections a human being can endure. Germs that know what’s good for them won’t come anywhere near me!”

“Oh Bridget, you have changed so much,” Mom lamented.

“Of course I’ve changed. Claire is out there all by herself. How can I not change? I have to find her.”

“Well, you can still change your mind…”

“No Mom, there is no way I’ll change my mind. This is something I really, really have to do and I won’t be on another planet, you can get hold me there, you know. Tony says one can pre-book phone calls at the Botsalo Hotel in Palapye. You can also leave messages. I’ve written the number underneath the postal address. He’s already booked for Friday evening at 8 o’clock. That’s 6 o’clock here in England. Wait, I’ll write it down for you.”

I took the piece of paper with all the addresses and phone numbers I had, including the ones of the British High Commission in Gaborone. I scribbled down ‘BOTSALO Hotel in Palapye phone 6:00 Friday night’.

“Sorry we can’t see you off at the airport on Tuesday, Bridget. You know, Mom is teaching again…”

“I know.”

“Phone us the minute you land, so we don’t have to worry. Oh dear, Botswana is so far away! You do know what happened with that airplane last week.”

I knew. Reports of the crash had been splashed all over the media. 169 lives lost. I could hardly have missed it.

“Thanks Dad, very encouraging. Don’t worry; I’ll do my best to make sure I arrive safely in Gaborone.”

“Oh Bridget…” Mom clutched me and cried a little more.

I felt like crying just watching her. My heart ached seeing my parents like this. When would I see them again? I couldn’t allow myself to think that way. I pulled myself together and hugged my parents goodbye and they boarded the Cambridge bus.

Two days later, I also said goodbye to Grandpa.

“Take care of yourself, love.” He looked sad. “We’ll see you soon.”

“Not to worry, Grandpa. I’m sure I’ll be back with Claire in tow,” I promised without knowing if I could keep my promise. He waved to me until I had disappeared behind the luggage check.

We landed in Gaborone’s small airport on 15 September. I stepped down from the 30-seater plane with wobbly knees after nearly 14 hours, a stop-over in Kinshasa and a bumpy transfer from Johannesburg’s Jan Smuts Airport to Gaborone.

On that day, I became one of the lekgoas; expatriates, who stay only a while before moving on. A few years are in the blink of an eye for the mighty Kalahari. I had much to learn.

That the passage of time is slower here; that the Tswanas take everything in their stride, sometimes maddeningly slow. That they commune with their ancestors and find it strange that we don’t; that not all witchdoctors mean well.

Perhaps things would have been easier, if my own ancestors had become involved somehow. Perhaps. But perhaps everything had to happen just the way it did…

The shrilling of the phone made me jump. I didn’t answer. I wanted to be alone with my thoughts — my life in Botswana. Working was no longer an option. When the ringing stopped, I made myself a cup of tea in the kitchen, put the receiver next to the phone and settled into the comfy armchair by the window.