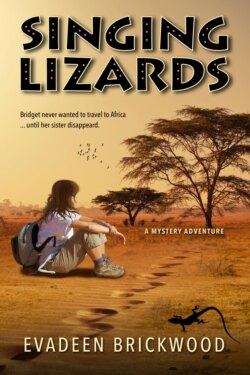

Читать книгу Singing Lizards - Evadeen Brickwood - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2

ОглавлениеTony had agreed to meet me at the airport. He could hardly refuse to help me, but it was also awkward. We didn’t know each other well and Claire was our only link. Would we understand each other? These things went around in my mind when we took off from Jan Smuts Airport.

The small passenger plane had hit a few turbulences while negotiating the space over a vast expanse of bush land. All that to the soundtrack of Simon and Garfunkel playing on my walkman.

The constant ups and downs left my stomach hanging a few inches above my head every time we hit turbulence.

Lucky for us, the stewardess had only served a snack of dried biltong meat, a Bushman specialty we were told, and salted peanuts. Nevertheless, I eyed the paper bag neatly tucked into the net in front of me. Would I have to use it? But my stomach behaved.

When the plane landed safely in what seemed to be the middle of the savannah, everybody clapped with relief. The smell of wilderness and a wave of hot air hit me as I walked the short distance across the tarmac to the quaint airport building. There was so much blue sky, so much savannah. The air glimmered above the landing strip, drenched in harsh sunlight. For a second I had to squeeze my eyes closed.

This was it.

This was Africa! The place that Claire had longed for.

How different everything felt. I had left behind England, dressed in the rainy colours of early autumn, and stepped into an African spring day: bright, hot and dirty green. September was early spring in Botswana! I had nearly forgotten that the seasons were reversed in the southern hemisphere. I slowly took in the earthy smell.

Picking up my luggage and having my passport checked didn’t take very long. Just long enough for me to admire the modern interior of the airport building. Was it my imagination or did the airport personnel look happier than their London counterparts? Their movements seemed less hurried and I didn’t remember seeing anyone smiling at Heathrow.

The queue moved past one of the cleaning ladies taking a rest, leaning against a stone container with some tropical plant. She greeted me with a broad, happy smile and so did the next one, who mopped the floor around our short queue.

When it was my turn at the passport check, the uniformed African official said, “Welcome to Botswana, Miss Reinhold. Enjoy your stay...” as he handed back my travel document.

This was so not like the oily-grinning officials in the movies, wearing ill-fitting uniforms, with the power to throw an innocent traveller into jail just for looking at them the wrong way.

“Thank you.” I smiled back and walked on.

There was a line of trolleys waiting for us. I heaved my bags on a trolley and marched toward the exit, a number of well-dressed businessmen right in front of me. I saw a double-chinned Indian lady in a bright-green sari and dripping with sparkling jewellry herd her four children deftly toward the sliding doors. Doting family members welcomed them and took luggage and children off her hands.

A young man came bounding towards the glass door. It was Tony, tall and handsome in washed-out jeans and a casual shirt. His dark, unruly hair was longer than I remembered and his bright eyes contrasted starkly with his tanned face. Gold-rimmed glasses gave Tony an air of learned sophistication, despite the three-day stubble on his chin and cheeks.

Sadness washed over me. It had been seven weeks since Claire’s disappearance and Tony was the only real link. For a brief moment we clung to each other. It was somehow okay to greet him like an old friend, talk to him as if we had been close forever.

“Hi there sis,” Tony finally said and cleared his throat.

“Hi Tony,” I sniffled and peeled myself away.

He turned to more pragmatic matters. “Come, let me push that for you. How was your flight?” We moved.

“Long. We stopped over in Kinshasa for a couple of hours. Thank goodness I had my walkman with me.” I tried to speak in a normal voice.

“Yep, music can be a lifesaver on a long trip. The car is this way.”

I just followed Tony and the clattering trolley down the near-empty parking lot.

“When we landed in South Africa, I saw so many houses with swimming pools. We waited in Johannesburg for over an hour in the transit area. That was quite boring.” I tried to sound carefree.

I opened the zip of my backpack and pushed the walkman inside, parting with my travel companion for the first time since London. But now I had Tony to talk to.

“Yes well, it’s a different lifestyle here,” he said and stopped behind a dirty, blue Toyota Corolla, fumbling for his car keys.

“You mean people in Botswana also have swimming pools in their gardens?”

“Well of course. Not in a village like Palapye, but there are plenty in Gaborone and Francistown.”

I was duly impressed. Imagine, having your own swimming pool!

Tony tossed my bags into the boot of the Toyota and abandoned the trolley. He opened the car door for me and I gratefully plunked myself on the passenger seat. After a few turns around the parking lot, we pulled into a long, straight road through the savannah. The earth was very red and dotted with pale green shrubs. I was tired, but far too excited to sleep.

“Everything is so dusty here. And look at all this red colour,” I said.

“Oh, that’s because of all the iron oxide in the soil and it hasn’t rained yet. It doesn’t rain here in winter,” Tony pointed out. “Nature explodes when the rains come in late spring, or so I’m told. Should be anytime now.” That was curious. It rained a lot in England, especially in winter.

“And here I thought nature had already exploded.”

“Ha, just wait and see. Close your window or the air conditioning won’t kick in.”

I cranked up the handle. “Are we going through Gaborone?”

“No, Bridget, we’ll drive straight to Palapye.” Tony turned left into what had to be the main road, judging by the three dusty cars that passed us. We travelled east now.

“Oh, why is that?” I had been looking forward to seeing Gaborone, where Claire had lived for all those weeks we had been separated.

“We have to get to Palapye before dark. We can go to Gabs soon. On the weekend, perhaps,” Tony said, turned his head and hooted.

Palapye. It was the name of the rural village where Tony now worked at a vocational training centre - close to the Tuli Block - and closer to Claire. At least it was my hope. The Tuli Block, a remote nature reserve, where the Zimbabwean and South African borders met with Botswana’s.

Claire had been so excited to see the elephants there. Staying in Gaborone without her must have become a pain for Tony. Then there must have been all those questions. Questions he had no answers for. At least not yet.

Tony had brought something to eat and drink, because we would be on the road for some time. I opened the brown paper bag with sandwiches and cans of coke.

“So you’re trying to avoid the traffic then?” I asked, taking a sip of foaming coke.

“No, Gabs isn’t that big. There won’t be much traffic around this time.”

“I see. So, why can’t we drive after dark?” I munched on a cheese and ham sandwich, mildly interested and suddenly feeling very tired.

“Because of the cattle and goats. They tend to lumber into the road at night and sleep on the warm tar. Nights can be quite cool around here,” Tony said.

“Really, cattle and goats?”

“Yep, can be dangerous in the dark, if you travel more than 5 miles per hour,” Tony said patiently. I considered the cattle and goats for a moment.

“It’s only early afternoon. Does it take that long to get to Palapye?”

“No, a couple of hours now, but nightfall is much earlier here. We are closer to the equator, you know.” Really?

“Hmm, I see. What about lions and zebras? Do they also run into the road?” I took a swig from my coke to wash down the crumbs.

“Not around here they don’t,” he laughed. “You’ll find wildlife further up north in the Okavango Delta, in the Tuli Block and so on. This here is more farm country.”

“I see.”

Too much information to take in on my first African day.

Some of the coke spilled onto my jeans, when Tony slowed down for some women with bulging blankets wrapped around them, balancing large bundles on their heads. I wiped myself with a paper tissue that Tony handed me and studied the landscape while there was daylight.

All I saw was reddish sand, bushes and grey gravel on either side of the tarred road. Now and again a dilapidated thatched house. The hills in the distance looked inviting. Dreamy somehow.

I wasn’t used to seeing Africa properly yet or I would have noticed the villages, animals and heaps of Shake-Shake cartons next to the road. Shake-Shake was Botswana’s most popular beverage: thick, sour sorghum beer. More food than drink.

Then I began to see wooden poles and wires whizzing past. And fences.

“Why are there are so many fences all along the road?” I asked and yawned.

“That’s to keep the farm animals away from the road,” Tony said. I was confused.

“Didn’t you say they run into the road anyway?”

“The cowherds don’t always keep the gates closed, so it’s better to be on the safe side,” he said. “Friend of mine got into trouble a couple of weeks ago. He hit a cow and had to pay an arm and a leg for it. His car was scrap as well, but he only had a scratch on his forehead.”

“Oh, that’s ... awful.”

“Yes, it is,” Tony agreed and swerved around a pothole.

I couldn’t help wondering how an accident like that would have made the headlines in Cambridge. ‘Young Teacher Hits Cow in Road with Golf GTI. Car and Cow Both Deceased. Farmer Demands Spot Fine from Injured Driver.’

“We are passing through Mochudi. Over there by the hill is a small clinic run by a German doctor, Dr. Ritter.”

Mochudi. I flinched. This was the place where Claire’s car had been found abandoned in a field. Would Tony stop to show me the spot? But he didn’t.

As we headed further east, Tony pointed to a hill with a white building to the right. Dr. Ritter had been in the country with his wife and five children for over ten years. His small but well-equipped hospital was preferable to bigger ones in the cities.

“You looked for Claire in that clinic, of course.” I already knew the answer.

“Of course, all the hospitals were searched.” Tony’s gaze was fixed on the road, which was a good thing really, considering the cows and goats and all that.

I took Claire’s first letter out the backpack. A well-read piece of paper. There were photos in the airmail envelope. One showed my sister in Peru, leaning against a ruined wall. Another one was at home in our kitchen. I was on the third photograph with my arm around her, together with Mom and Dad.

Looking at my parents brought on a pang of guilt and homesickness. Was it right to just leave like that, leaving them to worry about me too?

It was done, I decided. I was in Africa now and there was no turning back. I squeezed the backpack down in front of the seat and put my bare feet up on the dusty dashboard, hoping that Tony didn’t mind. Then I re-read the letter for the umpteenth time:

‘Gaborone, 11 June 1988

Hi Foompy,

Arrived in Gabs, as the locals call the capital. It’s so small even compared to good old Cambridge. I have seen only two traffic lights so far … It’s really cold at night, because, can you believe it, it’s winter here. One moment I’m in balmy England in June and now it’s winter. Only at night, though.

It’s hot and dry during the day. Who knew that winter could be like that? It was so cold last night that I crept into my sleeping bag. Must buy a proper thick duvet and blankets tomorrow, if I can find a shop. Tony’s lucky he doesn’t get cold easily. He’s been here for almost a month, so he should know the shops in Gaborone.

I swear I saw ice-covered puddles this morning. The gardener, who looks after the company house garden (and it’s a huge house), watered the lawn yesterday and… ‘

The letter went on about the features of house and garden and how sweet Tony had been. He had greeted Claire with a bunch of flowers at the airport and after delivering her luggage to the company house, they had gone to the office to meet her new colleagues.

Those colleagues were something else. Comical, almost. I had to smile again as I read on. There was this obnoxious fellow draughtsman from Chicago, who liked to wink suggestively at her.

‘…Maybe he has a nervous tick...’ Claire wrote, but I already knew from her subsequent letters that he didn’t.

Rather a case of thinking that the sun shone out of his backside, leaving females mesmerized. Chad Sullivan fancied himself a ladies’ man. Apparently, women ran for the hills when they heard his pickup lines.

‘…Then there is Liesl, the dull, blonde girlfriend of a young engineer called Desmond Kahl. She spends the whole day in a back office with her boyfriend, but doesn’t seem to work. I’m sure she dresses like her mother.

Wolfgang Klein, head of the design team and my direct boss, is firm and fair with his staff. He’s a tall, good-looking man in his mid-fifties and very smart. The design team consists of Wolfgang’s right hand, an engineer called Werner Pfeiffer, his spunky PA Emily van Heerden, Kgomotso Min the Tswana bookkeeper, whose stepfather’s a Chinese banker and Thomas Taylor, a senior engineer, who looks like a wild Scotsman with a flaming red beard. A clutch of less interesting people complete the team...’

Claire got on easily with people, but she didn’t like the corpulent office manager, Mr. Feindlich. I knew that his name meant ‘hostile’ in German. Telling.

‘…Mr. Feindlich took me to a French (!) restaurant called The Bougainvillea yesterday. He filled me in on my colleagues over lunch. The man had nothing good to say about Emily. Thinks she’s a slut — imagine. How can a manager be so crude? And I didn’t have the impression at all. In fact I rather like Emily and Kgomotso. You know I always go by my instinct.’ (I knew) ‘Does this man think I don’t have a brain to make my own mind up?’

I sighed. Would I meet any of these people while I was in the country?

‘…Mr. Feindlich likes Desmond and his girlfriend a lot. Liesl seems to be some relation of his. She’s quite young and chubby, but looks a lot older in a cute pug-faced sort of way. I’m sure she dresses like her mother. Feindlich wanted me to go shopping with her. Oh dear! Came up with some excuse. He’s going to hate me, if he finds out that I’ll go shopping with Emily and Kgomotso instead…’

So there was a clue. Did this Mr. Feindlich really hate Claire? Perhaps not. Don’t read clues into everything, I reprimanded myself. I had scrutinized the letters over and over, but couldn’t find anything enlightening. They had little more than sentimental value in my quest to find Claire.

‘…Emily is intelligent and headstrong. 23 and quite pretty with her light-brown hair. She’s a South African from Johannesburg and goes home to visit her family at least once a month. Kgomotso is Emily’s best friend. The two girls are stark opposites in the looks department, but they have the same liquid movements and friendly personalities. I’ve been to the smaller company house in Tsholofelo. They share it with two other people. Tsholofelo is a nice suburb. Emily loves to wear sunglasses and has at least five pairs. She’s not aware of it, but men are quite attracted to her. Mr. Feindlich is aware of it ...’

Claire didn’t write much about Kgomotso in her first letter, but I gathered that the three of them had become pals. I tried to picture a company house with Claire in it.

“Bridget, hey!”

“Umm, yes?” I must have dozed off for a while. A street sign read ‘Mahalapye’.

“Wake up.”

There were soldiers in the road. We were stopped at an army roadblock.

“What’s going on Tony? Is there something wrong?” I was alarmed. Bombs, street battles…

“No, nothing wrong. Sorry I forgot to tell you. Soldiers often search cars for weapons and things to do with the military. Leave it to me. Just smile.”

I rubbed my eyes. Tony was ordered to open his boot and I smiled.

The soldiers looked very young with their machineguns slung over one shoulder and seemed nervous. Were they trigger-happy? The harsh tone and the guns made me nervous too. I had never been so close to a real weapon before. We had to produce our passports and were waved on after a couple of minutes.

“That was scary,” I said and started breathing again.

“Better get used to it. They have roadblocks in the cities as well.”

“What happens if they actually find something?”

“Well, that rarely happens. A British salesman, who travelled with an old camouflage jacket from his army days, was interrogated for a few hours. Poor chap was still rattled, when he told us his story at the Botsalo Hotel.”

Botsalo Hotel. That’s where I had phoned Tony a couple of weeks ago.

“Very comforting,” I mumbled. How could people get used to something like that?

“Just don’t carry anything army green in your car and be friendly,” Tony said.

Okay, nothing army green, I thought sleepily. The sun now wavered over the hilltops and a fine mist rose over the fields, but it was still early afternoon.

I ate another sandwich and offered Tony the one with salami. He took one bite and then stared at the road again. Did he expect a cow to come charging out from behind a hut any moment now?

“Tony, tell me something about Palapye.” We had just passed a road sign with the name of our destination on it, just below the name ‘Francistown’.

Tony took a deep breath as if he was waking up from a dream.

“Well, there isn’t much to tell. Don’t be surprised if you don’t see the houses at first.” He took another bite from the salami sandwich he had deposited on the dashboard.

“Most of the kraals are hidden by motsetsi hedges and dried branches.”

“Motsi what?” I didn’t understand.

“Motsetsi. Tall evergreen plants. Then there is a new tar road all the way up to the new training centre. That’s where I work. It’s the only road in the village. The alternative is to drive or walk through deep sand past the kraals. We are staying in the complex up by the training centre. There is a high school. And the Botsalo Hotel, of course.”

Tony took another bite and finished the sandwich. He chewed, wiping his hand on a tissue.

“The complex is behind the training centre. The houses are all fenced in. Very monotonous, like a garden colony in the sand,” he said.

“I can help you plant a garden,” I offered spontaneously.

Some green around the house would be nice and comforting like our back garden in Cambridge.

“Mhm,” Tony said.

“These green hedges seem a good idea,” I said, but the conversation was over.

We drove on and eventually, a dusty green road sign with ‘Palapye’ on it pointed right. Tony turned between an ancient-looking petrol station and a curio shop. The fast-sinking afternoon sun lent a golden sheen to the surroundings.

“And this is Palapye,” Tony announced.

This was supposed to be a village? Tony had been right, I didn’t see any houses. Just trees, hedges and dried wood to the left of the black new tar.

“Impressive!” I lied in jest and we both laughed.

There was surely plenty of nothing here. Not at all the vibrant, buzzing African village I had imagined back in England.

My vision was still adjusted to high-rise brick buildings in London, small spaces, the busy roads and traffic lights, billboards, shopping precincts, trains and buses. Lots of people. At home, nature was neatly packaged into manicured parks and fields outside of town.

“Not long now. By the way, that’s the local shopping mall.” Tony pointed to a short row of very dirty single-storey buildings with a broad walkway upfront.

He swerved around a few goats and a cheerful group of boys in ragged shorts. They edged into the road while pushing toy cars with long steering wheels all made of wire, waving at our car. Tony hooted and I waved back at them. They laughed and made faces at us.

Then the Corolla hummed up the long, black tar road to the vocational training centre, leaving the village behind.

I couldn’t help thinking that Claire had never even seen what I was seeing now. It felt odd somehow. I never wanted to live in Africa in the first place!

Soon we drove through the boom in front of the vocational training centre and we still hadn’t spoken a word about Claire.