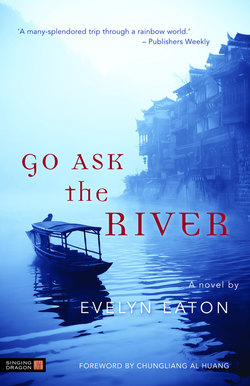

Читать книгу Go Ask the River - Evelyn Eaton - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOREWORD

CHUNGLIANG AL HUANG

In the poetry primer Three Hundred Poems of Tang Dynasty read by all Chinese students of literature, although it is common for the male poets included to use the female voice to write poems of love and sentimental longings, there is less than a handful of women poets represented. The same scarcity is also apparent in the definitive anthology of Tang poetry, The Complete Tang Poems; out of a total of approximately 2250 poets, only 130 women are listed. If we are tested on the annals of poetry, most of us probably can only name a handful of woman poets of distinction. The one for me has always been Xue Tao.

Through stories told by the women in our household, I first became familiar with the legendary Tang Dynasty poetess Xue Tao and her illustrious poems. Xue Tao, also known as Hung Tu (Hong Du), was celebrated not only for her genius and artistry as poet and calligrapher, but even more for her courageous and adventurous life as the renowned courtesan in Chengdu’s Blue House on the Silk (Brocade) River.

Many stories were told, imagined and fabricated about how she distinguished herself as the poet-scholar and official hostess at the governor’s mansion. In the world of the literati reserved for men of letters, she was highly respected, honored and sought after. All the more intriguing were her many romantic liaisons with famous poets during the high cultural period of the time.

When I met Evelyn Eaton at Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, in the late ’70s, we felt an immediate kinship. She told me about the amazing incident when she was in Sichuan, China, during the war as a foreign correspondent for LIFE Magazine. One day in Chengdu, she had an “out of body” experience, feeling as though she was a Chinese living in old China. She was drawn to follow her instinct and came upon the gravesite of Xue Tao, which led to a passionate obsession in researching the poet’s life and her poems. The book, Go Ask the River, Evelyn confided in me, felt as if it was channeled by spirit and dictated by her new-found ancestral lineage.

When Evelyn sent me the last copy of this out-of-print book, I also had the feeling that those English words can be read by the modern Western reader to sound genuinely Chinese in their nuanced exotic expressiveness. We suspected that somewhere in Evelyn’s psyche the Chinese soul resided deep. We were both enthralled with this awareness. Evelyn had guided me into the private sanctum of Xue Tao’s inner life which had been, until then, only a mythic and romantic imagining. Suddenly, her poetry became vividly alive and deeply meaningful to me.

After Evelyn died in 1983, her daughter Terry and I convinced my publisher Celestial Arts to bring out the book, which had enjoyed only a brief period of success, in 1990.

Another two decades had passed, and this edition came into being fortuitously during a lovely dinner with Jessica Kingsley, in the spring of 2010 after the book launch in London of my four perennial editions with Singing Dragon. Between our celebratory toasts, I shared with her the story of Evelyn and Xue Tao. Our mutual excitement about the possibility of bringing the book back was immediately ignited.

Returning home, I opened my treasured first edition of this book. It contained a letter I had saved from Evelyn, thanking me for the rebirth of this book, with a wish that I should provide a Foreword for the new edition. Regrettably with the 1990 edition, which had a fine introduction by Paul Reed, I was unable to provide the Foreword in time.

Now Go Ask the River is again resurrected. It is my honor and pleasure to recount my friendship with, and to remember, Evelyn Eaton with much nostalgia and the joy of magical reflection. I also wish to congratulate Jessica Kingsley and her staff at the Singing Dragon for their dedicated vision and mission to bring out, always, truly unique and fascinating books for their readers.

Before you embark on this “back in time” journey with Evelyn, I will offer this story of Xue Tao. The child prodigy, at eight years old, upon hearing her father making up this couplet:

“In the desolate courtyard, the Wu-tong (Phoenix) tree reaches to the sky, soaring in the cloud.”

immediately followed with:

“Perches for the birds from the South and the North its branches’ fallen leaves dance in the draft of the wind.”

Xue Tao’s father, it is told, in awe of her prodigious talent, remained in silence for a long time.