Читать книгу Fatima Meer - Fatima Meer - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 4 Wentworth Days: 1931–1932

ОглавлениеEach Wentworth day was adventurous, some more so than others and it is the latter that I remember.

The sum total of our family when we moved to Wentworth was my father, my two mothers, my three brothers and I, my uncle AC (Ma and Papa’s cousin, the son of their Uncle Chota Meer) and his family and my uncle Cas (Amina Ma’s brother). Uncle AC though soon left with his wife, Gorie Ba, and his son, Haroon, to establish his own household in Pine Street6 in Durban. From time to time family members from Dundee, Waschbank and Kimberley, would join our household.

My early recollections of Wentworth are hazy. In my mind’s eye I can locate three bedrooms, a sitting room, a kitchen, and washroom with a tap and a crude outlet for water. A veranda led to the house and to the shop adjoining the house. Papa had rented the house and shop. My mother Amina Ma was going to be the shopkeeper, her brother, Cas, and when possible my Uncle AC would also help. The idea of a shop was exciting to us children. We identified it with sweets, but there was very little of that delicacy, or any delicacy for that matter, in our shop.

I became conscious of trees and birds in Wentworth. Grey Street had been all concrete, not a tree or flower in sight. Now I awakened each morning to the sound of birds. I would lie in bed looking out of the window to see the birds flying and twittering about in the branches. In my imagination they had human experiences, forever preparing for weddings, parties, or for school or work.

Papa would help embellish my fantasies, but Amina Ma would snatch me out of such musings. ‘Brush your teeth and wash your face!’ was her morning call, as she readied me for my first madressa lessons and the lift I had to take with Papa. We were each given a bowl of warm water. We brushed our teeth with our fingers, with powder ground from embers collected from the grate. Amina Ma then settled us down with bowls of porridge and coffee and bread.

Every morning when Papa went to the printing press, he took me with him and dropped me off at the madressa in Clairwood. He had a car and a driver, a man called Billah. After work Papa lay in bed reading and writing. Sometimes he pottered about the house and made medicines. I thought of him as a genius inventor.

Amina Ma was nineteen or twenty years old at that time, and judging by her photographs, very pretty. But I did not think of her in those terms. I only thought of her in terms of her authority and the fire of that authority. Amina Ma made very cautious purchases for the shop from a man who openly admired her, but she barely gave him a look beyond ordering and paying for her purchases. As part of his attention-seeking, he gave us children a sweetie now and again.

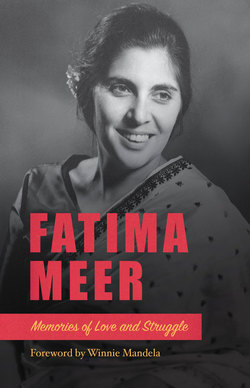

Amina Ma and Ma.

Her brother, my Uncle Cas, the only family of Amina Ma we knew, loved me very much and he paid me special attention. Uncle Cas made no secret of the fact that I was his favourite child.

While living in Wentworth Uncle Cas married Baby Idries. Amina Ma seemed upset about this. Perhaps she felt that he ought to have consulted her and included her in his marriage arrangements since she was his older sister. He took me to see Aunty Baby and while I was eager to go meet this new aunty, Amina Ma wasn’t at all pleased that I went with him.

Once Uncle Cas took me for a holiday to his house in Clairwood. I enjoyed myself there. We would get up in the morning and feed the fowls. He seemed to have hundreds of them. Aunty Baby was a very good dressmaker. She took me to a very special hairdresser. There was magic in his fingers, she said. If he trimmed your hair at the edges it would grow very long. My hair did grow very long. Amina Ma was very pleased.

I was conscious of being pampered, not only because I was the only girl in the family, but also because I was deemed to be pretty. I had golden brown hair, hazel eyes and an almost European complexion, inherited from my blue-eyed, near-blonde mother.

Sometimes Papa would go away for several months on trips to collect payments from the subscribers to his newspaper. I missed him greatly and his homecoming, when he returned laden with presents, was sheer happiness.

I remember on one of his homecomings though he went straight to bed, without picking me up or hugging me. Instead he lay in his bed weak and shivering, and our mothers piled him with blankets. From where I stood in the corner of the room, afraid and isolated, I heard Papa say: “Behn too is not coming near me. I must be very frightening.” That hurt me. I wanted to run to his bed and crawl under his blanket, but I dared not. I fretted all day. How could Papa think I did not wish to be with him?

Often Papa told us stories, and he allowed us to jump on his stomach. I found the soft white flesh of his belly most attractive. I never saw my mothers’ bellies. They were always discretely covered up. In fact I do not even remember seeing their arms, even when they bathed and washed us.

We did not have electricity in the Wentworth house – we used candles. Papa would place a lighted candle on each of the wooden posts of his double bed. In retrospect I think how dangerous that was, and then the thought comes to me that my father was somewhat reckless, and that I have acquired that streak from him, through example, because such things are not genetically inherited, however much one may think they are.

At the back of our house, on a higher ridge was my friend Sissie’s house. Sissie was an Afrikaner girl and I enjoyed her company. She was my age, but more important, she was a girl. Her mother was a large woman, with a great big sore on her leg.

Our favourite pastime was playing house. My mothers had bought me a small grass and cane table and two chairs from a vendor who had come by the house. With just those three items of furniture, Sissie and I constructed a whole house in our minds and on the ground on which we played. We could be anything we desired, and we had all sorts of domestic adventures.

One day we were dining on onions on my little grass table when a snake came slithering by. We were shocked into total silence. We saw the snake snap up and swallow a frog, and we watched mesmerised as the frog disappeared and the snake’s thin body became bloated with the frog. We never said a word to each other, nor to anyone else. It was as if that snake had cast a spell over us. We moved only after the snake disappeared to wherever it had come from. Then we went rather hurriedly into our respective houses.

Ma would sew together fabric samples and I would have patchwork dresses of sorts. Maybe I only had one such dress, but then I also had one dress that was a little girl’s dream, or rather nearly had it. Ma had sewn a sleeveless, frilly dress for me of a gossamer, fairy-like fabric, bluer than the blue sky and yet not quite blue. It was turquoise, the sky mixed with green of the land around me. I imagined myself in it, but it was snatched away from me before I ever wore it.

Someone in the neighbourhood, someone important to my mother, had a baby and the dress was presented to that baby. I was very disappointed, but I did not complain. I have never in my life seen a comparable dress and yet I suppose it must have been pretty ordinary. What could have come off a hand sewing machine in Wentworth in 1932?

Then came Ramadan and my first fast. I had just turned four. Ma had cut up one of her trousseau long scarves – chocolate-coloured and heavily embroidered in gold and made me a dress with matching trousers. To help me while away the last hours of the fast which can become trying, I was dressed in this finery and taken for a drive to the second Meer home in Durban – Uncle AC’s flat in Pine Street.

Uncle AC’s parents made a huge fuss of me and my mother Ma sent for flowers and made me a garland. I have never felt so decorated and honoured in my life. Even my reception in Surat in 1995 – when I was presented with an award and draped with so many garlands that the photographer had to ask me to remove the garlands so that he could see my face which was lost in the roses – did not compare with the thrill I experienced on that day. The fast was more than worth it. I felt so grown-up, so important.

Eid followed Ramadan and was very special. We got new clothes and were taken to Durban to be fitted with new shoes. I set my heart on a black patent leather pair with white bows. The shoes were displayed in the window of the shop at the entrance of the passage that led to my father’s printing press. I could not have known greater joy than when Papa bought the pair for me.

On Eid day we woke to the aroma of frying samoosas and boiling cardamom milk, to our mothers’ distant voices from the kitchen, and the hazy memory of pillowcases put up the night before at the end of our beds for presents that would be brought by the angels – the faristas. We cast aside the clinging sleep and jumped out of bed to look at our presents.

In my pillowcase I found a large celluloid doll in a blue dress. I shouted for my parents, “Ma! Papa! The faristas came!”, and I ran to show them my doll. My brothers came after me with their motor cars. Our confidence in our parents was strengthened. They said the faristas would come, and they had, and they cared sufficiently for us to bring us toys.

My new Eid dress was pretty and Amina Ma put an apron over it. Papa gave us Eid money and Ismail was allowed to take us for a train ride to nearby Jacobs where we spent some of this money on ice creams. I wished Eid would go on forever, but our Papa said that all things come to an end and so did Eid.

Other charmed days followed. Papa brought Allah Pak into my life. Solly, Ahmed and I sat in a circle on Papa’s bed and he said, “Close your eyes tight so that everything is black and no light can enter.” And we did just that. “Keep them closed”, he said, “until I say open.”

We opened our eyes to a feast before us. Each of us had a plate of sweets and fruit. We looked in wide-eyed wonder at Papa, Ma and Amina Ma. We asked, “Where did all this come from?” Papa said: “It all comes from Allah Pak.” I asked, “Where is he?” and my father said he is far, far away in the heavens. “He sent us these things from all that distance?” I asked. My father confirmed that he had. And my mothers smiled approvingly as my father added, “Allah Pak can do anything. He is all-powerful. He looks after you. He looks after all of us.”

I constructed my own image of Allah Pak. I identified him with my father and he took on his gender, but I saw him in a red dress, reclining above me in levitation. I did not share this image of Allah Pak with anyone. It was a secret in my mind, a secret between Allah Pak and me. One day I was walking with my uncle Gora Papa, my father’s brother. I saw something red levitated far above me in the sky, and I called in great excitement, “Allah Pak!” and Gora Papa said, “That is a kite”.

Ma told us about the Prophet Muhammad and we listened in rapt attention as she told of the time he was dying.

“The Angel Jibreel comes to take away our souls and we die,” she said. “He comes at his will, and he takes our soul at his will. We are all helpless before Jibreel, but in the case of Prophet Muhammad, Jibreel knocked on the door, and Bibi Fatima the Prophet’s daughter asked, ‘Who is it?’ and Jibreel said ‘It is I, the angel of death’. Bibi Fatima said, ‘I will not allow you in, go away’.

“The Angel knocked again. This time Prophet Muhammad asked his daughter who was at the door and she told him it was Jibreel. ‘Then why did you not let him in?’ She said ‘He wants to take your soul. I won’t let him in.’ Then the Prophet told her she had to open the door. ‘It is a courtesy that he asks to come in. He can come in without opening the door. He is paying his respect and you must respond with respect.’ Then with tears streaming and sobbing, she opened the door. Jibreel entered and asked Prophet Muhammad if he was ready and could he take his soul and Prophet Muhammad said ‘Yes’, and then with great gentleness, Jibreel took the Prophet’s soul and bore it away to Allah.”

I was deeply impressed by this story and by another Ma told us about the Prophet.

“It was the custom in those days among the wealthy to bring in a wet nurse to nurse a baby and she would take the baby to the countryside and nurse him there where the air was clean and fresh. So the baby Muhammad was sent to spend the first few years of his life with Dai Halima, his wet nurse. Dai Halima had her own baby and the two babies suckled at her breasts. When the two boys were about three years old and were playing together, two angels came and took Muhammad away, and opened his heart. The little friend ran in consternation to his mother, screaming that two men were attacking Muhammad. Halima ran to rescue him. She found a laughing Muhammad and no sign of the two men. Muhammad told her not to be alarmed. It was only the angels, ‘they opened my heart and cleaned it!’.”

Ma added that Muhammad was thus without sin. He was pure. He is the model for us all to follow.

One of the earliest stories my father told us which left a lasting impression on me was about King Solomon’s justice:

“Two women came to King Solomon with a baby and each claimed the baby belonged to her. To prise out the truth King Solomon said to the two women ‘Since you are both claiming the baby, why don’t we settle this by cutting up the baby and giving each of you half?’ The false mother accepted the solution but the true mother said she would give up her claim as she could not allow her baby to be cut up. She wanted her baby to grow up and have a good life, and if the other woman could give him that life, she could have the baby. So King Solomon satisfied himself as to who was the real mother. The people marvelled at his justice and that has remained recorded for all time.”

I could not have been more than four years old when my father told us this story, but I remained troubled for days that the false mother could have opted for half a baby. I could have asked my father to explain how any human being would want another human being cut up, only it wasn’t done to ask questions, and therefore it never occurred to me to ask. The thing was to listen and if there were questions, to hope that they would be answered somehow in the course of telling the story. So my questions remained unasked, and therefore unanswered.

The madressa I went to was at the Motala’s home in neighbouring Clairwood. The father and son ran a shop. The mother and daughter-in-law ran the house – two rooms at the back of the shop. There were no children in the house so the daughter-in-law, who gave me my first lessons in Arabic, welcomed me most warmly. The book I was to learn from was one Papa had made for me. He had written the Arabic alphabet at the back of an advertisement which had a picture of a girl drinking a popular cold drink called Sun Crush from a bottle with a straw. Daughter-in-law and mother-in-law were critical of this human image on the back of Allah’s alphabet. They were a simple and gentle couple but they made me critical of Papa, and Papa was someone only to be admired. I wished he had bought me a proper book instead of making me one, and that too on the wrong paper. It seemed that he could not afford to buy a book.

The most interesting thing in the Motala home was a basket hung at the entrance from a rafter. The Motala’s kept mithai – sweetmeats – in it. I discovered this on my first day. Lonely and upset, tongue-tied and weepy at being left with strangers, I did not respond to my first lesson. To entice me, the older Mrs Motala brought down the basket and withdrew from it delectable portions of mithai. I was sufficiently comforted to start my first lesson. The next day I kept looking at the basket. The daughter-in-law saw this and inquired if I wanted mithai. I nodded vigorously. She gave me some and as I guzzled it, she gave me a lesson apart from Arabic. Very gently she explained that I came there to learn Arabic and she was there to teach me. I did not come to eat mithai and that was the last mithai I would get because there was no more.

The next morning I was reluctant to go to madressa. “Yesterday you were so keen, what is the matter today?” Ma asked. I said there was no more mithai today. They were horrified when they learnt I had asked for mithai. Ma told me how wrong it was to ask anything of anybody outside of the family. Amina Ma gave me a slap and sent me off with Papa making it quite clear that I went there to learn, not to eat mithai. I got down to my lessons after that. I was left at the Motalas all day. Papa usually fetched me on his return home.