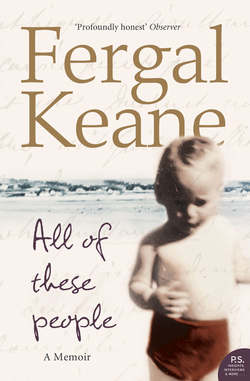

Читать книгу All of These People: A Memoir - Fergal Keane - Страница 5

PROLOGUE

ОглавлениеEarly in the new year, 2004, I was due to meet a friend for coffee in Chelsea. As I waited an elderly man entered and went to the front of the line. I felt a flash of annoyance and tried to attract the attention of the staff. ‘He’s jumping the queue,’ I said. But nobody heard me. The manager came and showed the man to a table. He turned, slowly, and I looked into the face of my father.

In the fourteen years since his death he had not changed.

My father did not recognise me but I knew him: those poetic lips, the melancholy vagueness of the old king fighting his last battle, the same shock of greying black hair, the thick-rimmed glasses, the tweed hat and scarf I gave him once for Christmas, the aquiline nose – the Keane nose! Crossing O’Connell Bridge in Dublin one day Paddy Kavanagh had turned to my father, his friend, and remarked: ‘Keane, you have a nose like the Romans but no empire to bring down with you!’

The man in the coffee shop was not, of course, really my father, but it was his face I saw. After being seated at a table near the window he had begun to talk to himself. I heard him. An English accent – upper class, not at all like my father’s. ‘I want to admire the magic,’ he said, and made a grand, kingly gesture, waving his hand. The manager laughed.

They both laughed. It was the kind of language Éamonn, my father, would have used. Expansive. I want to admire the magic…

This book began as an attempt to describe my journalistic life and the people and events which have shaped my consciousness. I had come through several traumatic personal experiences and arrived at middle age – a time when men often collide with their limitations and feel the first chill of mortality. I needed to take stock of where I had come from, examine the influences which had formed me, and to look at where I might be going. There were also certain resolutions to be made in the way I lived my life. Chiefly they concerned the risks I was taking in different conflict zones of the world.

What I did not understand then was that another imperative would emerge. This book would also become a journey in search of someone I had loved but with whose memory I was painfully unreconciled. When I tried to describe my journalistic life and world, I found my father waiting for me at every corner; the past intruded so acutely on the present that I found myself pulled constantly towards a man who had been dead for more than fourteen years. For much of my adult life I had lived in confusion about my father: thoughts of him made me feel both angry and sad. I could never understand him or the manner in which our relationship had affected my life.

When I look now at my journalism, at the preoccupations which have remained constant – human rights, the struggles for reconciliation in wounded lands, the impulse to find hope in the face of desolation – I know that I am largely defined by the experiences of childhood. Since much of that childhood was framed by the realities of growing up in a household dominated by my father’s alcoholism, it might be assumed that I found my father’s influence to be a wholly negative one. This book acknowledges the pain of the past, but writing it has revealed to me that both my parents gave me gifts that were profound and lasting. Their passionate natures and belief in justice were my formative inspiration. They were, above all, people of instinct. I doubt that either of them had a calculating bone in their bodies.

I did not always realise the good they had handed on; I too often saw the past through the prism of an angry, alienated child. But a personal crisis in the closing years of the last millennium set me on a journey towards understanding my father. I travelled part of his road of suffering and found that I was more like him than I knew.

Two physical landscapes dominate this book. One is the country in which I grew up and which, for all my exile’s tendency to criticise, I love and feel very proud of. I was a child of the Irish suburbs. The familiar worlds described in the conventional Irish narratives – misery in the tenements, a happy romp through the fields to school – were not mine. I was born of middle-class parents and grew up in the 1960s and ‘70s amid the death throes of traditional Catholic Ireland. I saw the emergence of a modern state at a time when one part of the island was descending into sectarian war and the other, my own country, was experiencing a social revolution unprecedented in its history.

The other landscape of this book is Africa, a place I loved from a distance as a child and which would draw me back again and again as an adult. Ireland and Africa are bound together for me. Events in Ireland have often helped me to make sense of what I saw in Africa, and my experiences in Africa, particularly in the age of apartheid, helped to illuminate possibilities of change in my homeland. I regard both as home in the larger sense of that word: they are places where I can feel a sense of belonging. In Africa I witnessed the death of people I knew. I saw friends taken away before their time. I saw the very worst of man and felt death brush my own shoulder. But I also met the best friend of my adult life, a man whose willingness to forgive was an inspiration.

Writing this book I have also tried to answer some fundamental questions: why was I willing to risk my life repeatedly? How did war change me? Why did I go to the zones of death? I have found that the motivations were as complex as the consequences. By the time I drove into Iraq during the war of 2004, a perilous drive from the Jordanian border to Baghdad, I had been a journalist for twenty-five years, fifteen of which had been spent reporting conflict.

I recently wrote down as many of these war zones as I could remember – Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Albania, Burundi, Congo, Cambodia, Colombia, Eritrea, Gaza, Northern Ireland, Sudan, Philippines, Rwanda, South Africa, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Lebanon…all places where circumstances had reduced the daily lives of men and women to misery. I found that as I travelled the zones of conflict there was much that seemed familiar, echoes of the history of my own country. As a boy in primary school I had listened to legends and half-truths. I had heard the stories of an Irish war handed down by former combatants in my family. I was conscious too of the stories we were not told – of civil war and atrocity, the lies of silence used by our leaders to bury the past. Those echoes became louder as I wrote this book.

I have been well rewarded for my travels. My reporting of war has won plaudits, awards, public attention. Yet I found the longer I stayed on the road the more I became aware of the psychological backwash of war. This, of course, touched the participants and victims most of all, but for the professional witnesses there was also a high price to be paid, not mitigated by the fact that we had chosen to put ourselves in the line of fire.

For me the greatest consequence of life at war, particularly after the Rwandan genocide of 1994, was a feeling of guilt. The cataclysm which engulfed the Great Lakes region of Africa in the late spring of 1994 left many of the witnesses with lasting feelings of responsibility, or in some cases a rumbling but impotent rage. Sometimes you could experience all those feelings within seconds of each other. We had watched the unimaginable – the slaughter of nearly a million people in one hundred days – and we had survived. All of my friends who covered Rwanda came away with something more than memories: we were, in different ways and with varying degrees of intensity, haunted. In my case the story followed me for a decade. It follows me still. Rwanda led me into two extraordinary relationships: one an encounter of love, the other a confrontation with a man whom I felt myself loathing and fearing, and who in the end I would have to face in a courtroom in the middle of Africa.

While writing this book I have been surprised by the number of times I laughed at the recollection of this or that event and how inspired I have felt at the memory of certain individuals. Even in the worst of situations there have been kind gestures, compassionate acts; often these kindnesses have come from those who have been most abused, people who insisted, when we met, on recognising our shared humanity.

The title of this book, All of These People, comes from a poem by the Ulster writer, Michael Longley, one of the most sensitive chroniclers of the pain caused by the Troubles. It is his tribute to those who have inspired him; I carry a little photocopy of this poem wherever I travel in the world.

All of these people, alive or dead, are civilised.

The civilised are those who can love, forgive and hope. The world is full of them. My mother was one such person. My father too.

In this account there are individuals whom I have left out, either because they would not wish to be included, or because doing so might put them in the way of harm. In describing the relationship with my father, I am conscious that it is only my version of events, my direct conversation with somebody who is long gone but whose presence remains a constant in my life. Others will see him differently and remember different things about him.

I hope that anyone reading this book will come away from it with a sense of optimism. I am an optimist. I believe there is more good in humanity than evil, and that we are capable of changing for the better. This is the continuing lesson of my personal life as much as the public sphere in which I have operated. I make my claim on the entirely unscientific basis of one man’s lived experience: it is the view from the long journey, not blind to the madness but awake to our finer possibilities.