Читать книгу Being Chris Hani's Daughter - Ferguson Hani - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

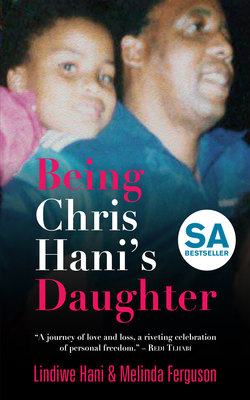

CHAPTER 4 Daddy

ОглавлениеOver the years many people have asked me what it was like having Chris Hani as my father.

I believe every little girl, if she is lucky, considers her father her hero. I was no exception. I didn’t realise that my father was the Chris Hani until after he died. To me, he was just Daddy. Yes, I acknowledge he didn’t live with us like so many of my friends’ fathers did with them, but that made no difference to me. This was our lived existence. I knew no other way.

Most people find it absurd that, as a child, I didn’t know that my father was an exceptional freedom fighter. That’s because my parents succeeded in making sure that I had the most normal childhood I could possibly have. My father made sure to phone us and speak to each one of his daughters while he was in exile. The conversations were never about world affairs. Instead, I would tell him that I came first in a race or that there was a girl at school who was bullying me. Not matter what I chose to tell my father, he would listen intently and give me advice as though I was discussing the freedom of Nelson Mandela. I now realise that that’s one of the reasons he is one of the most beloved leaders of the struggle – his capacity to listen to every problem as though his life depended on it.

I often wish I had asked Daddy more about his experiences as a boy, when he was growing up in South Africa. If I’d known I would not have him around for much longer, I would have grabbed every hour we had together, to find out about his childhood home and family, what inspired him as a boy growing up in a small village, and what he dreamed about when he went to sleep at night under the huge black sky.

What I do know is that my father arrived on this earth on 28 June 1942 in the tiny rural Eastern Cape village of Sabalele in Cofimvaba, about 200 kilometres from East London. It was the same year that the first Archie comics were published, there were race riots in Harlem, New York, and Jews in European Nazi-occupied territories were ordered to wear a yellow Star of David.

Daddy was christened Martin Thembisile Hani, but later decided to give himself the name Chris, which was actually the name of his younger brother. His father, my paternal grandfather, Gilbert Hani, was, according to Daddy, a man who would love to have been educated but was instead a semi-literate migrant worker on the mines in the old Transvaal. My grandfather later found low-paying work as an unskilled worker in the building industry, as well as trying to eke out a living as a hawker. Daddy hardly ever saw his father, who was away from home most of the year, struggling to make a pittance.

While Daddy’s family – his brothers Uncle Victor and Uncle Chris and his mother, Nomayisa Hani – continued to live in Cofimvaba, my grandfather, whom I grew up knowing as Tamkhulu, moved to Mafeteng, about 76 kilometres south of Maseru. Mafeteng literally means ‘The Place of the Passers-by’.

Occasionally, Mama would take us to visit him but I always dreaded it because I truly disliked the woman he lived with, the one who turned out not to be my grandmother, as I had thought – a fact I only found out a few years after I had met her. I found her very harsh and abrasive, not warm and loving, the way I imagined a grandmother should be. This, I believed, was a bone of contention between father and son.

So when it was announced it was time to take a trip to Mafeteng, I went into total whinge and protest mode. Weirdly, Tamkhulu – much like my maternal grandfather Ntatemoholo Sekamane, who had blue eyes – had green eyes and was light skinned. He always wore thick, square black-rimmed glasses and, even though he intimidated me, now and again he showed signs of kindness by giving us chips and cooldrinks. His paramour, on the other hand, could be needlessly cruel and this was exacerbated by the fact that she was an alcoholic. One night when our mother had left us there the woman threw a terrible scene and was so verbally abusive that Momo took us down the road to a family friend Me’ Mphu Mofolo until Mama returned to pick us up.

Daddy’s mother, my grandmother Nomayise – Makhulu, as we got to call her – never left the village of Cofimvaba. My father was the fifth of six children, three of whom died shortly after birth. “Because,” said my dad in an interview with historian Luli Callinicos just weeks before he was assassinated in 1993, “in the rural areas, in those days there were literally no health facilities. A family was lucky to have the whole offspring surviving. If 50 per cent survived, that was an achievement.”

From the stories I’ve been told, life was extremely harsh for the Hani family. My Makhulu, who was completely illiterate, was basically a single parent while her husband was away working. She did her best to raise her three surviving sons on her own, working herself to the bone to make ends meet from subsistence farming.

Up to the age of seven, I had never laid eyes on my Makhulu, nor my uncles Victor and Chris.

Sometime in 1988, it was decided that it was worth the risk to smuggle Momo, Khwezi and me into South Africa to meet Daddy’s family. This was a direct request from Daddy – I guess he was concerned that time was passing and that it was imperative that we meet his family, especially my Makhulu, who was getting older. I have a vivid memory of driving towards the South African border, all excited and bright-eyed to travel ‘Overseas’, into the big unknown. As we got closer to the border post, we were bundled into the boot of the car. Instead of feeling fearful in the cramped, dark space, all I felt was great excitement to be going on this big adventure. We crossed over the border without incident and once we’d travelled some distance, we were let out the boot. As we made our way to Cofimvaba, it was like exploring some new, exciting foreign land. On the way, we stopped over in Queenstown and stayed with the Baduzas, who were relatives of our mother. I was completely in awe of their huge mansion-like property, just as I imagined Daddy’s Warbucks house looked. That night we slept in a double bed with blue satin linen. There were little silver salt and pepper cellars as well as a bell on the table to summon ‘the help’. Apart from the hotel on the Baltic Sea in Russia, this was the most luxurious night I’d ever experienced.

The next day we got up at the crack of dawn and drove for the next 2.5 hours to the very rural village of Cofimvaba, off to see my grandmother and my uncles. It was something of a culture shock to travel on untarred red dirt roads, to see rondavels and the villagers of the outlying areas. Knowing that this was where Daddy had been born brought my little heart enormous pleasure. This was the place where, as a boy not even old enough to go to school, Daddy had woken up each morning to look after the family’s small herd of livestock.

As the car pulled up in front of a tiny house, my Makhulu appeared. This tall, dark and stately woman hurried towards us and simply pulled us into her arms, babbling away in a string of isiXhosa that I did not understand even if she had spoken slower. For me, it was love at first sight. Makhulu was kind and open-hearted; she just kept touching and kissing us as though we had appeared in a dream and were now standing in front of her.

As per tradition, a goat was slaughtered in front of us to welcome us home. I was horrified, watching the meat being cooked and knowing that we would be expected to eat it. Yho! I was one of these wussie kids who, although I loved meat, I refused to eat the meat of an animal that was killed in front of me. I was about to refuse to eat the goat that Makhulu proudly placed in front of me when I felt Momo glaring daggers at me, so reluctantly I started nibbling on a tiny piece.

On seeing Daddy’s two brothers, Uncle Victor and his baby brother Uncle Chris, I was transfixed by the miracle of genetics; it was astonishing to see how much they looked like my father. But it was not only their looks that had me staring; on hearing their voices and watching their mannerisms, it felt like I was seeing Daddy’s doubles. Time flew by far too quickly and soon the moment arrived for us to return home to Maseru. Back in the boot, as we neared the South African/Lesotho border, my heart and mind were filled with such joy, having finally met another part of our family. It made me feel even closer to Daddy, especially meeting and bonding with my Makhulu. Out of the boot back in Lesotho, I could not wait to see Mama to tell her of our big adventure.

Although I never heard Daddy speak about his aunt, his father’s sister, in Daddy’s interview with Luli Callinicos he mentioned her as having a huge influence over him as a child.

“I remember as a small boy I used to have a fascination of books, I would read those books although I understood very little. [My aunt] encouraged me and taught me a few necessary rhymes and began to open up a new world even before I got to school. A world of knowing how to write the alphabet, how to count, in other words not only literacy but numeracy.”

So by the time Daddy was seven years old, when he was enrolled in the Roman Catholic school nearby, he was already able to read. “When I went to school I was in a better position than most boys in the village, and I remember the principal of the school got encouraged, how I would read a story and actually memorise that story – without looking at the book, I would actually recite it word by word.”

I grew up often hearing what a mission getting to school was for Daddy. He had to walk over 20 kilometres to and back from school every day, five days a week, and then on Sundays another 20 kilometres to get to church and back. I cannot imagine me or my sisters ever showing that kind of commitment for school, let alone church! All that exercise probably helped to make him the fitness fanatic he would later become. By the time he turned eight, he was an altar boy, feeding into his dream to become a priest. “I was under the spell and influence of the priests, the monks and the nuns,” he told Luli. “There was something one admired in them – a sense of hard work, selflessness. These people would go on horseback to the most rural parts of the village, taking the gospel to the people, encouraging kids to go to school, praying for the sick and offering all sorts of advice. In other words, they were not only priests, but they were nurses, they were teachers, they were social workers. I must submit that had a very, very strong impression on me and in the formation of my character.”

But my Tamkhulu was completely against the idea of priesthood as a vocation; he desperately wanted Daddy to be educated and to live a better life, a life that had never been available to him. So Daddy had to give up his dream of entering the priesthood.

It was during this time – Daddy must have been eight or nine – when some of his teachers joined the Campaign against Bantu Education. Their commitment to protesting against the introduction of inferior Bantu Education lit a fire for justice in Daddy at a very early age.

In 1954, at the age of 12, he enrolled in Matanzima Secondary School in Cala, Transkei, which was named after the head of the Transkei, Chief Matanzima. This was the year that the apartheid regime forced Bantu Education into black schools, a system described by Daddy as “designed to indoctrinate black pupils to accept and recognise the supremacy of the white man over the blacks in all spheres”. It upset him deeply and was another fire that inspired him to become involved in the struggle for equality and freedom in South Africa.

Daddy did very well at school, especially in English literature and languages. He landed up writing his Standard 5 and Standard 6 examinations in the same year and was promoted to high school. He was awarded a Bhunga scholarship that allowed him to leave the small village school and enrol for high school at Lovedale College in Alice in 1957.

It was here that Daddy’s activist spirit would really be awakened. He soon got involved in student politics, first joining the Unity Movement’s Society of Young Africa, then six months later he was recruited by Simon Kekana, head prefect at Lovedale and chair of the African National Congress Youth League, to join the League. Getting involved in politics at school was illegal, so everything Daddy did at the time was in secret and underground. My father was deeply affected by the events surrounding those who were arrested and charged during the Treason Trial of 1956. By the time he was 15, he had been heavily influenced by the writings of Govan Mbeki on the problems and struggles in the Eastern Cape. When I think of what I was up to at that age – dressing up for socials and reading Danielle Steele – I am in total awe of my dad.

By 1957, Daddy had already started reading journals and newspapers such as The New Age, Torch and Fighting Talk by Ruth First, which added to his political awakening and introduced him to Marxist concepts.

“There was a page in New Age which dealt with the struggle of the working class throughout the world,” he told Luli Callinicos in their interview. “What was happening in the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, the GDR, China – the life that people were building there. And that had an appeal in my own impassionate young mind. Given my background, I was attracted by ideas and the philosophy which had a bias towards the working class, which had as its stated objective, the upliftment of the people on the ground.”

Daddy matriculated in 1958, achieving really high marks in all his subjects – English, Xhosa, Latin, History, Mathematics and a subject called ‘Hygiene’.

When news arrived that he had gained admission to Fort Hare University, a relatively liberal campus considering the apartheid regime’s iron grip over South Africa and its neighbours at the time, the entire Hani family, especially my Tamkhulu, was elated.

“I got a bursary and a scholarship to go to university because I was performing rather above average,” he downplayed his achievements in his interview with Luli. “When I went over to Fort Hare, I won a government loan to go to university. I think basically that is what helped me to go. It was extremely hard. One would have only one pair of shoes, one jacket and it was not easy because other students from families which were more comfortable than mine, the kids would be better clothed than myself. But I had accepted the fact that this was not important for me. It was through this spirit of self-sacrifice and accepting that the priority was to get my education. There were a number of us coming from rural areas who got their pocket money because parents sold hides and wool whenever it was the sheep-shearing season. We had some sheep and some cattle and goats at home. So my father bought a sewing machine for my mother. Now and again through that I could get a bit of pocket money whilst I was at Fort Hare.”

Daddy had a never-ending thirst for knowledge. From the moment he became a student at Fort Hare he embraced his new intellectual environment and he read and read and read – English, Latin and Greek literature, modern and classical; he literally gobbled up all this new information. I think his early fascination with Catholicism inspired him to be particularly drawn to Latin studies and English literature.

I remember my father often sitting with a book, reading for hours, when we lived in Dawn Park – he took his deep thirst for knowledge everywhere he went. There were even stories that he had copies of Shakespeare and Virgil in his backpack when he was on the run from the apartheid forces during the exile years.

At Fort Hare, he was soon devouring Marx and any literature that criticised South Africa’s racist capitalist system. By the age of 19, Daddy joined the South African Communist Party, and quickly converted to being a full on Marxist.

“In 1961, at Fort Hare, I was doing my third year, studying for a BA degree and majoring in Latin and English,” he told Luli Callinicos. “I am approached by some comrades who apparently had been moulded or welded into a Communist Party unit by Comrade Mbeki. So, in 1961, I joined the Party and I began seriously studying Marxism, the basic works of Marxist authors like Emily [Burns] What is Marxism?, The Communist Manifesto, The World Marxist Review and a number of other publications. I began to read the history of our Party by people like Edward Roux for instance, Time Longer than Rope, giving the earlier history of the Communist Party.”

In the same year, uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the military wing of the ANC, was established. He was clear in his interview with Luli about why he was drawn to the SACP.

“I belonged to a world, in terms of my background, which suffered I think the worst extremes of apartheid. A poor rural area where the majority of working people spent their times in the compounds, in the hostels, away from their families. A rural area where there were no clinics and probably the nearest hospital was 50 kilometres – generally a life of poverty with the basic things unavailable. Where our mothers and our sisters would walk 3 kilometres and even 6 kilometres whenever there was a drought to fetch water. Where the only fuel available was going 5, 6 kilometres away to cut wood and bring it back. This was the sort of life. Now I had seen the lot of black workers, extreme forms of exploitation, slave wages, no trade union rights. Where it was said that workers create wealth but in the final analysis they get nothing. They get peanuts in order to survive and continue working for the capitalists. For me the appeal of socialism was extremely great. But I didn’t get involved with the workers’ struggle out of theory alone. It was a combination of theory and my own class background. I never faltered in my belief in socialism. For me that belief is strong because that is still the life of the majority of the people with whom I share a common background.”

The following year, in 1962, Daddy became one of the first volunteers for MK, which marked the beginning of his long journey into the armed struggle, a cause and approach he passionately believed in. Halfway through his studies, my father decided to leave Fort Hare to complete his BA at Rhodes University, which he believed was a better university.

During holidays he would return home to the village.

“I used to go and be with my mother, help her in the fields, growing maize and harvesting,” he told Luli. “Because, if you harvested probably 20 bags of maize, the rest would be sold to the white shopkeeper, because that was the only market available in the rural areas. It was the white shopkeeper who would buy at prices determined by him. In other words, I contributed even to the slender financial resources of the family by working very hard during holidays in the fields and also looking after the stock.”

In that same year, 1962, Daddy graduated with a BA degree in Latin and English and decided to pursue law. The following year he moved south to do his articles at the law firm Schaeffer & Schaeffer in Cape Town. He soon got caught up with his new life there, spending long hours with ANC icon Govan Mbeki, who became a mentor and father figure to him, as well doing volunteer work in trade unions. In the same year, at the age of 20, he was elected to MK’s highly secretive seven-man regional committee, dubbed the ‘Committee of Seven’, in the Western Cape.

“I became a member of the Committee of Seven, in overall charge of the underground of the ANC in the Western Cape,” he told Luli. “It [was] in the course of my activities within that Committee of Seven that I [was] recruited to become part of the MK set up. I [was] recruited into a unit and I began to operate in small ways, throwing Molotov cocktails, cutting telephone cables and all that.”

Towards the end of that year, Daddy had his first real run-in with the law when he was arrested, along with his friend and comrade Archie Sibeko, at a roadblock on their way to Nyanga East to distribute leaflets against the 90-day Detention law. After spending the weekend at Philippi Police Station, they were both charged under the Suppression of Communism Act for “furthering the aims of a banned organisation” and being in the possession of banned material. They spent the following 30 days in isolation cells before the trial began. I am sure Daddy was tortured during this time.

My father was found guilty and sentenced to 18 months in prison with hard labour. The exorbitantly high bail was set at £125. While out on bail, waiting to hear whether his lawyers would consider appealing the sentence, Daddy left the country to attend an ANC conference in Lobatse, Bechuanaland, known today as Botswana.

When news reached my dad, in February 1963, that his sentence had not been overturned, he and Archie decided to go into hiding. Daddy secretively travelled to Soweto, where he stayed underground with a family sympathetic to the struggle. In May 1963, along with a small group of exiles, my father set off for Bechuanaland and then on to Northern Rhodesia, today known as Zambia. This was to mark the beginning of Daddy’s time in exile. It would be almost three decades before he could return to South Africa.

As the small group of revolutionaries arrived in Lusaka, Zambia’s capital, they were all arrested. However, unlike his humiliating experience in South Africa, this time the court procedure was brief and soon they were free to travel across the Zambian border to Tanganyika, now Tanzania.

Within six months of arriving, along with 30 other MK cadres, Daddy flew from Dar es Salaam to Moscow, in Russia, which was then known as the USSR, to undergo military training. Out of Africa for the first time in his life, this experience must have been mindblowing and would influence my father deeply, both as a human being and a military man.

In his interview with Luli Callinicos, he explained what a mind shift landing in the USSR was. “I came from a very racial society and therefore the first time most of us as blacks are received as human beings, as equal human beings, we are received by people from the Central Committee who are based in a secret house, and at this time we have these white ladies actually cooking for us and looking after this place. So for us this is a new world. A new world of equality, of people where our colour seems to be of no consequence, where our humanity is recognised. We had not been exposed, we had not been to Britain. We had no comparative experience. So for us this strengthened our feelings, our strong feelings in socialism.”

Meanwhile, back in South Africa, on 11 July 1963 the core of MK, including Daddy’s mentor Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba, Ahmed Kathrada, Lionel (Rusty) Bernstein and Bob Hepple were arrested at Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, the underground headquarters of the ANC. On hearing the fate of the South Africans back home, it was decided that Daddy and the newly exiled cadres in Russia should intensify their training. So they extended their stay from six months to more than a year.

The time spent in Moscow drastically changed Daddy. Not only was he exposed to military training, the theories of guerrilla warfare and the politics of socialism, but also to the cultural richness of Russia. “We visit(ed) museums … concerts, the Bolshoi theatre … For the first time I actually watched ballet dancing. I mean a new world for us. We never saw it in our country. We begin to appreciate classical music. We moved around in Moscow in buses. Of course these were guided tours, and we don’t see starving people, we don’t see beggars. We’d go to factories and watch the Russian workers. Now of course I know that we were not exposed to everything that was happening, but that partial opening of the window into this new society served to strengthen our strong socialist convictions. I want to say, without reservations, that shaped my outlook, strengthened my politics … For me that was an unforgettable experience.”

Not only was he experiencing a cultural awakening, in Russia Daddy also learned invaluable military skills and his fitness levels peaked.

“Every morning we had to go out … on marches, tactical marches,” he told Luli Callinicos. “We had to go out into the Russian villages, set up camps there in the forests and the marshes around Moscow, and stay there and look at maps, orientate ourselves. We learnt topography, firearms, engineering skills, the manufacture of explosives and the use of standard explosives. So I was fit physically, I was in very good shape.”

In 1964, at the age of 22, along with 30 newly trained cadres, Daddy travelled back from the Soviet Union to Tanzania where they were offered a piece of land at Kongwa, 400 kilometres south of Dar. Daddy was put in charge of the team to set up a military training camp.

As the South African government tightened its grip on anyone who resisted the apartheid government, within a year many exiles had fled South Africa and soon the Kongwa camp grew to more than 500 strong. Daddy’s love for literature and education meant that he was much loved by the new exiles, as he spent many hours teaching adult basic education to counter the high level of illiteracy among the cadres who had all been exposed to the inferior Bantu Education system back home.

In 1966 Daddy was on the move again, this time back to Zambia. His Soviet training had prepared him well and he was put in charge of setting up a joint training programme with the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), preparing soldiers for a covert operation into Rhodesia. This would later become known as the Wankie Campaign.

But again Daddy came head to head with the law as he was arrested trying to re-enter Botswana. Fortunately, he was detained for only two weeks before being sent back to Lusaka.

On 2 August 1967, less than a week after my father turned 25, he led a group of soldiers across the Zambian border into Rhodesia. They entered the Wankie Game Reserve on their first covert mission and, on 13 August, after a heavy battle with the Rhodesian army, they successfully forced the army to retreat. And then, just 12 days later, they experienced another victory against the Rhodesian Army. Their spirits were high as they marched towards the Botswana border.

But their luck was not to last long. Within a week they were arrested by the Botswana security forces and, after an appearance in court, were each sentenced to six years’ imprisonment for possession of illegal arms. Again my father found himself behind bars.

Daddy eventually had his jail time reduced to two years and, on his release, returned to Zambia in 1969 to live with intellectual and struggle exile Livingstone Mqotsi in Lusaka.

But two years is a long time. Despondent and feeling let down by certain members of the leadership of the ANC who had done little to help them during their time behind bars, my dad and six of the soldiers who had fought in the Wankie Campaign drafted a letter, which become known as the Hani Memorandum. In this document they made explosive allegations against many members of the ANC’s leadership in exile.

We, as genuine revolutionaries, are moved by the frightening depths reached by the rot in the ANC and the disintegration of M.K. accompanying this rot and manifesting itself in the following way: The ANC Leadership in Exile has created machinery which has become an end in itself. It is completely divorced from the situation in South Africa …

We are disturbed by the careerism of the ANC Leadership Abroad who have, in every sense, become professional politicians rather than professional revolutionaries. We have been forced to draw the conclusion that the payment of salaries to people working in offices is very detrimental to the revolutionary outlook of those who receive such monies.

It was a very controversial and highly risky move, which was typical of Daddy’s outspokenness and fearlessness – action that saw him and the six other signatories expelled by the ANC NEC in exile. It would not be the first time my father would be disciplined by those within his organisation. The document furthermore criticised Joe Modise, then Commander-in-Chief of MK. As a result, seeds of bad blood were sown between Daddy and Joe Modise, who was so enraged by the Memorandum that he called for my dad to be executed for treason.

Oliver Tambo, then president of the ANC and supreme commander of MK, was also extremely upset by the Memo, afraid that the sentiments expressed would cause huge distrust in the structures of the ANC in exile. As a result, an urgent gathering was called to discuss the allegations, and the Morogoro Conference took place in Tanzania between 25 April and 1 May 1969. It was a watershed moment, resulting in wide-ranging changes to the political and military structures of the ANC.

At the Morogoro Conference it was recommended that Daddy and the other signatories of the Hani Memorandum be pardoned and reinstated as full members of the ANC and MK. A year later, in 1970, as a result of his uncompromising commitment, Daddy’s influence had substantially grown. He was 28 years old when he was elected to the Central Committee of the SACP.

Over the following four years Daddy would travel a lot overseas, but not the ‘Overseas’ of my childhood imagination; he visited Europe, spreading the ideals of the ANC and SACP while receiving further military training in East Germany. In 1973 he was one of the ANC delegates to the Southern Africa Conference of the United Nations’ Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in Oslo, Sweden. It was the same year he met Mama.

In 1974, along with Thabo Mbeki, Daddy was elected to the ANC’s National Executive Council, the two of them becoming the youngest members ever. Thabo, who was also a June 1942 baby, was just 10 days older than Daddy.

Daddy briefly returned to South Africa that year to help build the ANC underground. It was a top-secret visit, of course, as he was regarded as a dangerous terrorist by the apartheid government. After his stay, he left for Lesotho to carry on his work strengthening the ANC in South Africa from across the border, leading the MK units responsible for guerrilla ops in South Africa.

In that same year, Daddy and Mama – who were now married – relocated to Lesotho, Maseru, where they would live together as a family for the next seven years, welcoming all three of us girls into their lives.

After the shattering night of the Lesotho Raids in December 1982, it became clear that all of our lives, but especially Daddy’s, were in great danger. He was redeployed to Mozambique and for the following eight years he remained in exile, spending most of his time in Zambia.

While in exile, Daddy’s influence within the organisation and back home in South Africa grew enormously. Between 1983 and 1984 he was appointed second in command of MK and frequently travelled between Mozambique and Angola, where he helped address concerns among dissatisfied MK cadres who were threatening mutiny in the organisation’s military camps.

Daddy was forced to leave Mozambique when the Nkomati Accord was signed in March 1984 between the governments of Mozambique under Samora Machel, the leader of FRELIMO, and the then president of South Africa, PW Botha. Under the Accord, the two neighbouring countries agreed not to allow their countries to be used as launching pads for attacks on one another – in other words, not harbour ‘terrorists’ and enemies of the South African regime, such as my dad. As a result, Mozambique, a war-torn country economically dependent on South Africa, was forced to expel the ANC from their country. In turn, the South African government agreed to cease supporting RENAMO, an anti-government guerrilla organisation in Mozambique. Not surprisingly, the agreement was soon broken by the South Africans, who continued to clandestinely support the activities of RENAMO.

Just 10 months later, in January 1985, Daddy received the highest number of votes for a seat on the Politburo, at the SACP’s sixth conference. It was the same year that the first State of Emergency was declared in South Africa. The townships had become ungovernable as the power of the MK structures and NGOs grew among South Africans at home, resisting the apartheid regime.

Broadcast from various neighbouring African countries, Daddy often spoke on Radio Freedom, the ANC underground radio station, urging people to derail the apartheid military machine.

“If you are working in a factory which produces weapons, vehicles, trucks which are used by the army and police against us,” he advised listeners, “… you must ensure that there are frequent breakdowns in those machines you operate. You can clog some of them by using sugar and sand.”

By mid-1987 my dad had been appointed MK Chief of Staff. Over the next few years, under his leadership, campaigns to sabotage and destabilise South Africa intensified. He was always clear that the only way that white South Africa would ever wake up to the reality of the viciousness of apartheid was when they experienced terror themselves.

In an interview with The Christian Science Monitor, an international publication, he famously said: “When we began to attack targets in the white areas, for the first time white South Africans began to sit up and say: ‘This thing is coming.’ … When they actually began to hear explosions in the centre of Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban, they began to realise that what they saw happening in other countries … was beginning to take place in South Africa.”

Over the years, especially in the mid- and late-1980s, due to his uncompromising military approach, Daddy’s reputation grew to near-mythical status among young exiles and the oppressed in the country of his birth, especially among the militant black youth in the townships.

In 1989 Daddy moved to the big house in Woodlands, Lusaka. As one of the South African government’s most wanted men, he now had two permanent teams of bodyguards accompanying him around the clock – and, of course, the guard dogs in the garden I remember so well from my time there.

A few months after his move to Woodlands, in February 1990, the ANC and SACP were unbanned in South Africa.