Читать книгу Being Chris Hani's Daughter - Ferguson Hani - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

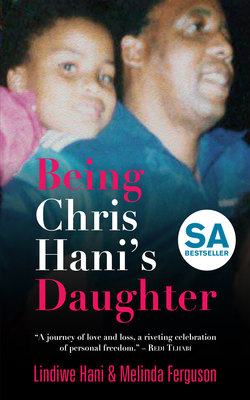

CHAPTER 1 My name is Lindiwe Hani

ОглавлениеI guess the best place to start a story is at the beginning. My name is Lindiwe Hani. I was born on 27 December 1980 to Limpho and Thembisile Hani. My father was also known as Chris. My parents named me Lindiwe, which in isiXhosa means ‘the daughter we have waited for’. In that year – a leap year – the world’s population sat at 4 434 682 000, the Voyager 1 space probe confirmed the existence of a moon of Saturn that was to be named Janus (or Janusz) – how’s that for prophetic – and Robert Mugabe was elected president of Zimbabwe.

I made my grand entrance into this world in the small village of Roma in Lesotho, at around 6pm. Apparently I slipped out of my mother’s womb after a mere two hours of labour. I grew up hearing my mother tell of how my birth was by far the easiest of all her three girls. By all accounts, from those who knew me, this easy birth set the stage for me to shine as a sweet, lovable toddler.

I was the last-born Hani daughter, after my eldest sister, Neo Phakama, who was nine years older than me, and my middle sister, Nomakhwezi Lerato, who was two years older. Nomakhwezi would come to be known simply as Khwezi. According to my mother, the births of her first- and second-born were excruciatingly long in labour. She would often tell us that Khwezi was a mother’s nightmare and cried for the smallest of things. So by the time I appeared, Mama was well and truly exhausted. Luckily, I rewarded her by being one of those contented babies who hardly ever cried and slept a lot. I was often told that as a baby I didn’t even mind lying in my own faeces. (Anyone who didn’t know my usually highly attentive mother could easily have put it down to child neglect!) The story goes that Daddy, who lived with us until I was almost two, came home one day and enquired, “How is the baby?” Startled, my mother – who was clearly exhausted, pushed to the limits from having three young children to tend to – jumped up in fright and went to check. She had forgotten all about me. I was happily playing in my crib at the back of the house in my thoroughly soiled nappy. That day my cot was moved permanently into the kitchen.

Daddy met Mama in 1973, seven years before I arrived. I loved hearing the story of how Uncle Jaoane, Mama’s older brother, played matchmaker. He had met my future dad at a political meeting in Botswana, and when he heard Daddy was off to Zambia, Uncle Jaoane asked him to take a handwritten note to his sister Limpho, who was attending a tourist conference there.

The story goes that for my parents it was love at first sight. They began dating, even though Daddy was on the move a lot, and within a year they were married. They didn’t have a big wedding; they simply went to a court in Zambia and tied the knot. My parents soon moved to Lesotho along with baby Neo, and Khwezi came along in 1978.

While my oldest sister Ausi Neo – or Momo, as she was affectionately known in the family – was my protector, Khwezi and I were like two she-cats at war. Due to the big age gap, Momo was often tasked with babysitting the two of us. It was more like having to play referee. Khwezi was the proverbial pain in my young behind. Because she was older than me, she often teased me about not being able to read like she could. When it came to having an argument, Khwezi was superior on every level, winning every debate and dishing out words like blows. She would often mock me by calling me ‘test-tube baby’ – of course, I had no idea what a test-tube baby was, I just knew it must be bad. Her teasing would send me into a flurry of tears, wailing my little head off, asking Mama, “What is a test-tube baby? Am I a test-tube baby?”

I remember one particular day when Momo was watching over us; I must have been about six. I was enthralled by cartoons on TV when Khwezi came in and snatched the remote. One of her outstanding traits was being a prolific TV-remote bully. Naturally, chaos ensued, with me screeching my little head off. Momo had had enough. She purposefully walked towards Khwezi, grabbed her skinny arm, marched her to the balcony and proceeded to hang her upside down from her feet, all the while telling her that if she didn’t stop bullying me, she would be dropped from the second floor. I stood in shocked awe and, of course, glee that my nemesis might finally be silenced.

As so many addicts seem to experience, I think I was born with a feeling of being lesser than. I often felt that Khwezi was Mama’s favourite and Momo Daddy’s. I envied Momo because she had lived longer with my father than any of us and he had taught her many exciting skills, like being able to swim. I was never overlooked or neglected, but I definitely had this feeling of being less loved, a complex I would carry with me into adulthood and often use as an excuse to get drunk and high.

While our mother loved and took great pride in us, she was also very strict; she was notorious for her temper and, like most mothers in those days, didn’t hesitate to dish out smacks. As a weapon of choice, she would grab whatever was in range, be it a dishcloth, a wooden spoon, or even a skaftini. My absolute worst punishment was when she instructed us to “go pick a stick so I can beat you”. This entailed a long, fear-filled walk to the garden to find the right stick. One could not be complacent in one’s own punishment; you had to make sure you didn’t pick some flimsy twig, or Mama would get her own weapon, which would invariably be twice as big and lethal as the pathetic one you’d chosen. But you also didn’t want to make the mistake of choosing the biggest one either, in case she settled for something smaller.

From the outset, Daddy was totally against smacking. I remember sitting with him one evening, when he asked me how I was doing and, without thinking twice, I told him I’d received a thrashing from Mama. He immediately left the room to speak to her. All I know is that after that conversation we never got another hiding again. Much later my mother told me that Daddy had warned her, “If you ever touch my children again, I will kill you.” The threat from a soldier trained by uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) clearly worked.

While Daddy did not believe in corporal punishment at all, in a lot of ways his form of discipline was far worse. He would sit you down, sternly tell you how unacceptable your behaviour was and how extremely disappointed he was in you. His strong words had the ability to cut right to the heart and invariably produced the intended results.

Although Mama’s whippings stopped, she was also extremely gifted in the area of verbal discipline. We got yelled at a lot. Her go-to admonishment was always how ungrateful we kids were and how hard it was raising us on her own. I learned to backchat pretty early on and so my stroppy self would answer back: “Well, we didn’t ask to be born!” I’m sure those were the times she really wished she could have given me a mighty backhand.

I was a mischievous child and went through a stage where I loved to play with matches. I’m not sure if I could have been labelled a full-blown pyromaniac but I was clearly fascinated by fire. I could spend hours watching as the orange flame devoured the stick until it almost singed my little fingers. At the very last second, as I felt the heat on my skin, I would unceremoniously drop the match.

And so the inevitable came to pass … Mama had just installed brand-new wall-to-wall carpets in the bedrooms and, as usual, I was playing with matches in our room when one singed my stubby little fingers. When I dropped it, the flame burned a deep hole in the new carpet. Instead of stopping, however, I thought it a great idea to continue my game in Mama’s room. Shock and horror – it happened again. Now what was a six-year-old girl to do? Well, I did what probably any other little girl would and kept dead quiet. Mama came home from work to find these burned holes in not one, but two of her new carpets. Naturally, my perfectionist mother went ballistic. She called all of us into the room and asked who had done it. Of course, Momo and Khwezi denied it – and I was so terrified that I denied it too. Well, somebody must have done it, said Mama. Still, no one said a word. To my sisters’ credit, they didn’t rat me out. So Mama punished all three of us and we had a good hour, if not more, of tongue-lashing.

Later, I would grow to understand the stresses our mother must have been under, which helped explain her notorious temper. She wore many caps, from being a single mother – even before Daddy was killed because he was away in exile for so much of our lives – to dodging bombs and bullets, all the while trying to raise three energetic, opinionated girls. She also had the added pressure of having to be a dutiful daughter to both sides of the family. Growing up, I was caught up in my own world, unaware of the burdens she shouldered. As I grew older, I would come to appreciate how extremely fortunate I was in my upbringing because my mother was an excellent homemaker – lawd, she could cook and bake! My favourite day was Sunday when Mama would begin baking treats for the week. There’d be scones, cakes, mince pies and, my favourite, apple pie.

Birthdays and Christmas were a huge deal in our family. On your birthday you’d be woken up with the whole family singing, treating the birthday girl to breakfast in bed, surrounded by a pile of presents to be opened in front of everyone. To top it off, there was always a big party to which all your friends would be invited. Mama, the gifted homemaker, would of course do everything herself, including baking the birthday cake and making treats like jelly in orange casings.

Christmas was the same, a huge affair with detailed planning and thorough execution. On Christmas Day we would wake up and run to the lounge to find presents delivered by Father Christmas under the Christmas tree. I remember asking her one Christmas, “How does Father Christmas come because we have no chimney?” Without missing a beat, she responded, “Via the TV antenna.” I was sold.

Funnily enough, even though our father was away so much, and although I missed the physical everydayness of him intensely, he was always there. He would phone almost daily, and we’d all have a chance to talk to him. I would breathlessly narrate my day, filled with “and then, and then” to which he would listen lovingly and patiently. Wherever he happened to be, be it Russia, Mozambique or Zambia, there were phone calls for birthdays, Father’s Day and Christmas Day. And of course our report cards were always sent to him. Heaven help you if you didn’t do well. Stern ‘talking-to’s could go on for what felt like hours. He was such a huge presence in our lives that even when we misbehaved, as soon as Mama said “I’m going to tell your father” there would be instant about-turn in our behaviour. For at least an hour.

The only thing we could never ask him was where he was at any given time; we learned that from the start.

Although we lived in a few different places in Maseru, the one I most clearly remember is Devcourt, where we stayed from 1983 to 1990.

Devcourt comprised two blocks of white-painted flats on one property. We were very close to the city centre and within walking distance from school. Behind the block of flats was rugged terrain, while on one side a huge garden spread out, with the most majestic willow tree.

Devcourt felt like living among an extended family. We were a very tight-knit community where neighbours knew each other by name and looked out for each other. There were so many kids living in the flats that during holidays and weekends I would leave home immediately after breakfast to join my gang of friends. The extent of our little tribe was when we all decided that we would orchestrate a mock wedding; Khwezi was betrothed to a neighbour Tau Tlabere. All the adults pitched in and the happy couple was even bought a suit and a white dress, plus there was food and ululations throughout that day.

My mother’s only rule was that you always had to be back for all meals and get your butt into the house before the streetlights came on. Most days I would come back purple-streaked from pilfering the blueberries next door, which we managed to steal by scaling the wall and returning with laps full of our sweet, sticky treasures. I remember one year one of our neighbours requesting some blueberries; in exchange she would make us a pie. This mission was incredibly tricky as we had to make sure that we were not caught by the owner or our curmudgeon of a caretaker, Ntate Baxtin. The grief we gave that poor man will probably come back to haunt me one day, but at that time tormenting Ntate was what gave meaning to our lives. We loved hiding in the stairwell and screaming our lungs off, waiting for him to hear us. As soon as we heard him coming, we’d scamper off as he angrily gave chase.

When not driving Ntate Baxtin crazy, we would play house-house. Sadly for me, being the youngest, I was always given the rather unenviable role of being ‘child’ when all I wanted to do was to graduate to being ‘wife’ and ‘mother’.

We would sneak food from the house and combine it with leaves, mix them up and arrange the mush in little silver tins, make a fire and cook it. It was paradise to play kick-the-can or hide-and-seek, or flatten cardboard boxes and slide down the hill. I was always filthy on my return home and most of the time my Goddess-of-Clean mother would make me strip at the door so as not to track my nastiness through the house.

Once there was a huge fire in the adjacent block of flats, forcing us to evacuate in the middle of the night. I remember watching from across the street, transfixed by the giant orange flames as they engulfed one entire section of the block, but really thankful that all of us had made it out okay.

Summer was my favourite time in Maseru. Mama would go to the Gatti’s factory and buy boxes of sticky-sweet ice cream and ice lollies, which cooled us down in the boiling 30-plus-degree temperatures in the capital.

We would walk or ride our BMXs to the Maseru club and swim the entire day, eating hot chips for lunch while lying on the steaming concrete paving around the pool. These were the milk-and-honey days of my childhood. Then there were the long drives out to Molimo-Nthuse, a small town in western Lesotho, which in English means “God help us”. The harrowing drive up the steep, endlessly winding mountain pass, where the roads were so narrow that it felt that we would fall off the edge of the world, still remains clearly carved in my memory today. The final destination always took my breath away: the hotel’s main building in the shape of a Basotho hat perched on stilts, surrounded by rivers and trees around which we would laze and enjoy picnics with our family and friends. As a child, I harboured ideas of buying that place and living there one day when I grew up. I still get pangs of longing to do that today.

I was an exuberant, busy child, not to mention helluva talkative. I remember my first day of nursery school vividly. I was placed into Mrs Da Silva’s class at the Montessori school, the same one Khwezi had attended. Within minutes, as Mrs Da Silva greeted with “Good morning, children”, I was in trouble. For some reason, I thought it would be hilarious to mimic her and repeated, “Good morning, children” in a mock teacher’s voice. Needless to say, she did not find me very amusing and called my mother to take me home immediately.

After a year with the overly serious Mrs Da Silva, I was enrolled at Maseru English Medium Preparatory School (MEMPS), or ‘Prep’, as we called it. Once again I was following the Great Khwezi legacy, floundering in her huge shadow. My clever and talented sister was a model student and the teachers were not shy at expressing their hope that I would prove to be as exemplary as she was. Ha! I was definitely not as studious and way more talkative, but I like to believe that what I lacked in scholastic discipline I more than made up for in cuteness and my fun-loving demeanour. On my first day in Class 1 at Prep, I was put in Mrs Lee’s class. She was a slim Irish woman with short brown hair; I loved her kindness and was especially mesmerised by her lilting accent. Within the first few hours, I made fast friends with Nomathemba Mhlanga, who would be my best friend throughout my entire school career.

On Saturdays, I loved getting ten Maluti from Mama and meeting my group of friends in town. Much to my horror, Khwezi often tagged along. We would buy tickets for the double feature, and during the reel change, before the second feature began, we’d walk across to the Maseru Café for snacks. After movies, Khwezi and I loved to go to the local mall, the LNDC centre, where we’d wander round the CNA, picking up comics for the week. Once we’d each had our fill, we’d swap them, so she’d buy Archie and I’d get Betty & Veronica.

Prep was a multiracial international school and from day one I was totally colour blind – I never felt any prejudice and didn’t even know at this stage what racism was or that we were geographically positioned in the middle of the bastion of segregation, South Africa. Until I actually saw it on a map, I thought that South Africa was some dangerous, faraway country ‘Overseas’, a place that we as a family were forbidden to enter, but this had no direct bearing on my young life. In fact, in my world, South Africa, Zambia or Russia – any place that wasn’t Lesotho – were all conveniently labelled ‘Overseas’.

Oblivious to the real dynamics at play in the country of my father’s birth, I attended school in my green-and-white checked tunic and went about my days in Maseru with the innocence of an ordinary child.

In retrospect, there were clues that maybe all was not as it appeared to be. Each morning, before driving us to school, Mama would make us stand a few metres away from our green Toyota Corolla, while she systematically opened the bonnet and then checked underneath before finally turning the ignition. It only dawned on me years later that she was checking for bombs, that our lives were under constant threat.

At the time, I believed that this was how all families began their days. I was completely confused one day when I tried to open a package of books that had been sent to me after I joined a book club in some magazine. Before I could get to my precious stash, my mother grabbed it out of my hands and tossed it off the second-floor balcony. I watched in complete disbelief, horrified by her sabotage of my treasure. Little did I know that she was expecting an explosion, a Boom! as it hit the ground. Thank the mother of all dragons, it simply hit the pavement below with a thud. I shot her as angry a look as my eight-year-old self could muster, then stalked downstairs to retrieve my books.

Years later I would understand that these were the consequences of being connected to one of South Africa’s most wanted ‘terrorists’.

Before Daddy was killed in 1993, he had had a number of death threats and lived through many attempts on his life. I would only really get to discover these things about him in the years after he was no longer with us, when I was obsessed with discovering everything I could about my father.

In 1981, in the year after I was born, a bomb was planted in Daddy’s car in Maseru, but for some reason it failed to go off. A few months later Daddy’s trusted driver, a man by the name of Sizwe Kondile, was abducted by the South African security police while driving my father’s car just outside Bloemfontein. Always loyal to Daddy, he refused to divulge any information about my father’s whereabouts despite being badly tortured. When they realised they could get nothing out of him, he was drugged and shot dead close to the Mozambican border.

A year later, on 2 August 1982, there was another car-bomb attempt on Daddy’s life, but this time the bomb exploded in the hands of the would-be assassin, a man by the name of Ernest Ramatolo, before he could get to Daddy. Less than four months later, in December 1982, the Lesotho Raids would target our entire family. After the Raids, Daddy was forced to relocate to Lusaka.

Over the following years, from the end of 1982 right until 1990, Daddy was not a permanent fixture in our lives because, over those eight-or-so years, he was based ‘Overseas’. Most of the time we would only see him once a year during our July holidays. I accepted this as normal as this was all I’d ever known. I would only come to terms with the sense of loss and abandonment much later in my life. As a child, you adapt to what is given to you and we simply got used to my father not being around.

Despite Daddy not being there physically, I had what seemed like a pretty idyllic childhood. There were times in the early years after the Lesotho Raid that my parents discussed relocating us to Zambia to be closer to my father. They finally decided that it was best that we were raised in Maseru because that was where Mama had been born; her entire family still lived there, providing us stability and support as we grew up.

As a result, we were very close to Mama’s family. One of my favourite places to visit was the home of our maternal grandfather, Ntatemoholo Sekamane. His garden was something out of a picture book, with a mini vineyard bursting full of plump grapes and the most amazing orange and peach trees. But heaven help you if you didn’t ask permission before picking the fruit. He was tall with very short hair and startling blue eyes. From the time I could remember, he walked with a cane due to the arthritis in his knee. Every time I asked him why he had such blue eyes he would glare at me and hiss ‘Voetsek!’, vehemently reluctant to discuss his lineage. Only later, through the family grapevine, I came to learn that his father was Scottish and his mother a Mosotho woman. In those early years, I resented the fact that I hadn’t inherited my mother’s green or his blue eyes. The home of my aunt Maseme – whom we affectionately called Sammy – was also a place of refuge for me; she too had a large luscious garden where I could lose myself for hours in a world of make believe.

I was always a child with a vivid imagination who loved to play dress up in my older cousin Pali’s sophisticated clothes. I was obsessed with her high heels. I loved getting lost in a fantasy world where I was either a princess or a lawyer. The scenario would invariably entail me meeting the love of my life, getting married and having a whole batch of children.

But my perfect world was rudely interrupted when Pali gave birth to a little boy, Tsitso. He was the first baby in the family after me, which really put my nose out of joint. Suddenly I was no longer ‘the baby’, the focus of the family. My princess life changed dramatically when little Tsitso came to live with us because suddenly everything belonged to this imposter. “Don’t make a noise, the baby is sleeping”, “Don’t eat that Purity, it’s for the baby”. Dethroned, I went out of my way to eat all the blasted Purity with a vengeance.

At the age of nine, long past my terrible twos, I suddenly became a tantrum thrower of note – in direct competition with Tsitso, who had graduated to toddler status. I was convinced that he was trying to take me out when one afternoon, this dangerous one-year-old intruder bashed me on the head with the end of a heavily weighted curtain rail. Somehow, he had managed to grasp it in his chubby hands, draw his arms back and bring it down with incredible force against the side of my head. Naturally, I took full dramatic advantage of my injury, wailing at the top of my voice – only to be told by the adults that he was “just a baby” and that it was “only an accident”. Sure! All I could see was his demonic smirk.

And yet, despite my run-ins with the toddler and Khwezi, when I recall my otherwise sheltered childhood, the best decision my parents ever made was having us grow up in Lesotho.