Читать книгу The Fetch - Finuala Dowling - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChas was about to re-enter his back gate when his eye was caught by a flickering light. Someone with a torch was making their way down the sandy path that led past the long hedge of Midden House to the tidal pool. He followed, intrigued.

“Who goes there?”

The figure turned around.

“It’s me, William.” He was carrying an old paraffin lamp.

“Hello, William! Come inside, join the party.” Chas gestured towards the side gate. “I would have invited you, but we all know what a hermit you are.”

“No thanks,” said William. “I was just checking if Nina was here. I didn’t think she would feel safe walking up this path alone in the dark. I reckon I’ll wait next to the pool and when I spot her about to leave I’ll walk beside her with my lantern.”

“Lucky I found you then, William,” said Chas, “because it would’ve been a fruitless vigil. Nina’s already gone home through the back gate. It’s about five metres from where she lives, so she really wasn’t in any danger.”

William took in the news with his head bowed. “Well, you should join your guests,” he said and turned to walk back up the hill. It was rare for him to converse so much. Whole days went by when he spoke fewer than ten words, and often those ten were received by Dib or the worms.

“No, stay,” said Chas. “I need a few moments before I go back in. I like the idea of being a fugitive from my own party, having adventures outside and then returning to yet another hero’s welcome. In fact, I’m addicted to the first moment of everything. The moment of entrance, especially. The frisson that runs around the room when one enters, everyone wanting to greet one at once, everyone wanting a part of one.”

“I don’t have that problem,” said William.

They had reached the public access to the tidal pool. The private staircase leading down to the water from Midden House was empty now: Chas’s guests had retreated to the stoep. The two men sat on the steps, looking out at the blues and blacks of the night-time sea. There was something mesmerising about the crash of wave upon wave on the back wall.

“So, what’re you busy on now, William?” asked Chas.

“I’m making an anemometer.” Seeing Chas’s incomprehension he added: “A little device that measures wind speed.”

“Sounds difficult. But then you like that kind of thing.”

“No, it’s easy. I just need some plastic cups.”

They sat in silence for a while, watching the water in the dark.

“It’s all about the wind,” said William, “the wind is almost everything. That’s why the waves here on the Atlantic side are so much bigger; it’s wind speed, but also the distance the wind travels across the water before coming up against an impediment.”

“Like the coast.”

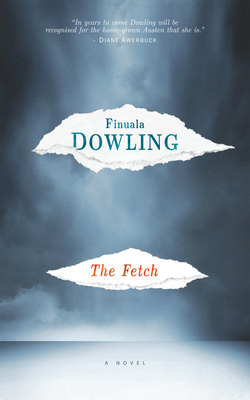

“Yeah,” said William. “They call it ‘fetch’. The distance a wind has travelled.”

Now that they were watching the sea with this information in mind, the waves seemed well-travelled. Desolate expanses of landless ocean came with them. Each wave, it seemed, aimed to clear the rocks and run up along the lawn of Midden House, but each was thwarted by the wall.

“Makes me think of death,” said Chas. “Life and death, I suppose. There’s a distance we travel before we meet our final impediment.”

William didn’t seem to find it necessary to reply, so Chas continued: “Have you ever thought what you’ll say if it turns out you’re wrong? I mean, what if we die and there is something there, after all? Some angels. We’ll have to say something. What’ll you say, William?”

William gave this problem some thought before he answered with another question: “What’ll I call them, these angels of yours?”

“I think you should address them as ‘gentlemen’, ” said Chas.

“Right, then I’ll say: ‘Gentlemen, I was wrong!’ ”

Chas threw back his head and laughed. His laugh was charismatic, as though he were handing out free tickets to a popular concert. But his mood soon turned reflective again. “Sometimes I find myself wanting to pray. In the city, at night, when I’ve been out somewhere … Churches used to be open at all hours. You could just go inside and pray. But they’ve all got security gates now. The sacristans lock them up.”

“Maybe they’re scared that people will break in and start turning water into wine,” said William.

Chas laughed again. Then he asked: “Do you have any dope? I feel this conversation will only reach its true potential if I’m stoned.”

“I’m growing my own now,” said William. “Come see.”

They stood up, shook the sand hoppers from their sleeves and found the sandy path once more. On the one side was the hedge of Midden House and on the other the mountain stream. It had run dry – they were at the late end of summer – but always when he passed it, William remembered a day when the stream was in flood and Chas had decided to parade in his mother’s clothes.

Some children weekending at the caravan park had dammed up the stream for their own pleasure. That hadn’t worried William, because he was on the beach, collecting flotsam that had washed up with the big storms of August. He was coming back from his southbound expedition with a real find, a lobster cage. He thought he’d take a shortcut instead of following the rocky coastline. He wanted to show Chas the cage. He could keep an animal in it, or maybe they could catch some crayfish themselves.

At first he’d thought it was a pretty girl fooling around, dressed up in her mom’s heels. She teetered across the grass in a camisole that only just made it past her hips, plenty of shapely leg on show, a sling bag over her shoulder and long ropes of beads around her neck. The boys at the stream stopped playing and watched her pass. She smiled at them, waved, but kept walking towards William. Aw, fuck! Oh, Jesus, no! he thought as he recognised Chas. He saw the boys go into a huddle and confer. Then they advanced in a pincer-like movement and started to close in.

Chas was beatific, completely consumed by creating his twelve-year-old boy’s version of a catwalk model, except that, unlike a model, he was grinning, as if to say: “Look at me pulling off this stunt!” He knew William had recognised him.

William measured the distances, triangulated them. He could not reach Chas in time to save him. All he could do was prolong his friend’s doomed happiness; make sure Chas was completely relaxed when the blows rained down on him, as he knew they would. So William smiled back, a congratulatory, “Good on ya, mate!” kind of smile.

The boys fell on Chas, ripping off the jewellery and the camisole. William dropped the cage and sprinted towards them. One of the boys punched Chas. The group dragged the slim, dazed figure towards the stream. William caught up with them as they began plunging Chas’s head under the water. His boyish chest was covered in goose bumps.

“Stop, you fuckers!” shouted William.

“Why? He your girlfriend or something? You fucking queers! Fucking moffies!”

“Leave him alone! What’s he done to you? Why’d you take all his clothes off? Maybe you’re the fucking moffies.”

To his relief, he saw Emmanuel, tall and gaunt, wearing a black rain cape, loping across the grass towards them, hoe in hand.

“Careful,” said William. “Here comes Death the Reaper.”

The bullies were distracted long enough for William to wrap his windbreaker around the shivering Chas. He urged his friend to hurry, get up. Then Emmanuel reached them and escorted them back to Midden House.

“But what I don’t understand,” said Mrs Fawkes later, “is why they pulled your clothes off? Punching you on the nose I quite understand. I mean, it’s not very nice, but that’s what boys do. Did you see them, William? What happened?”

Emmanuel had gone off with the broken strings of beads to see if he could fix them. He had already binned the ripped camisole.

William didn’t know what to say. He’d heard about Chas’s Uncle Ernie, who’d killed himself in a Durban hotel room, whose name couldn’t be mentioned at Midden House, certainly not in front of Mr Fawkes senior, at any rate.

“They were low-class children,” he said eventually. “Afrikaners, I think.”

“Ah,” said Mrs Fawkes. “That explains it.”

Screened by the milkwoods, William’s dagga grew around his cottage in leafy abundance.

“Hello, hello, hello!” said Chas when William held his lantern above the plants. “It’s a veritable forest. What do we do now? Harvest some?”

“Shh,” said William. “They’re sleeping. Come inside for some highquality THC.”

They entered through the back door of the cottage and were greeted by Dib, who twirled her tail against their legs. The place smelt of cigarettes and dirty carpet. An electric bulb, attached by copper and zinc wires to four fresh lemons, burned weakly.

“Please feel free to use the toilet while you’re here,” said William.

“I’m fine, thanks,” said Chas.

“It all goes down into a tank underground and turns into biogas,” said William. “I’m nearly off the grid, but I still use the plugs occasionally.”

“You actually cook off the energy from your poo?”

William nodded eagerly. “No shit!” he quipped.

Chas surveyed the clutter William had accumulated in his bungalow. “This place has changed a bit since your folks were alive,” he said. “Are you storing things for a garage sale or something?”

Empty vodka bottles were ranged along the length of the window sill. The kitchen table was covered with dozens of empty Marmite jars, all spotlessly clean. William picked one up. “How can you throw away something that fits so perfectly into your hand? Come, I’ll show you where I hide the weed.”

Except for a narrow path that wound between the piles, the floor of William’s cottage was taken up with a mishmash of detritus. William had collected his treasures in large baskets or stacked them in piles against the walls.

“So, do you have plans for all this stuff?” asked Chas.

“A lot of the electronics I can fix. Take this, for example – a first generation PlayStation. Someone just left it out with their trash, can you believe it?”

Chas looked as though he could very well believe it, but said nothing.

Accompanied by Dib, William led Chas through the maze to what had perhaps once been a conventional bedroom, but now contained, in addition to the bed, all the larger things William had collected from tips and dumps: a pinball machine, a lawnmower and several TV sets stacked on top of one another. A ladder stood against the wall, protruding up into a dark hole where a square of ceiling board had been removed. As if she knew what they were looking for, Dib climbed the ladder ahead of them. Her cat’s eyes peeped at them from the attic.

“I went up there once to fix a leak in the roof, and Dib just loved it, so I left it open. Now I hide my valuables up here.”

“Valuables?” asked Chas. “Considering all the junk you’re hoarding, I’d be interested to find out what you consider ‘valuable’. ”

William went up the ladder and reached into the recesses of the loft space. He brought out a small plastic bank bag of dope and handed it down to Chas. Then he reached in again and brought out a heavy-duty cloth money bag. This, too, he handed down to Chas.

“Have a look in there.”

“Damn heavy,” said Chas. He pulled open the drawstring bag. “Fuck me, William! Are these real gold coins?”

“Kruger rands,” said William. “Every time I get paid for a job, I buy more. If I’m going through a really lean patch, then I sell a few.”

“So you don’t like paying bank charges?” asked Chas.

“I don’t trust banks,” said William.

After William had put the gold back in the attic they went outside to smoke a joint. William’s entertainment area consisted of a patch of paving made from salvaged bricks. Chas sat on the weathered sofa wedged against the wall of the cottage. William sat on a gnarled tree trunk. Their table was the old plastic crate containing the quail.

Chas peered into the quail cage. “How do you kill a thing like this?” he asked. “I mean, if you’re really planning on eating it? Do you blow its head off with a gun?”

William laughed. “There wouldn’t be any quail left if you did that. No, I believe that you pop its head off with your thumbs, or stretch the neck out and use a pair of scissors. I haven’t actually tried it.”

He frowned because it was a cruel thing, to kill an animal. Still, it was worse to eat meat you hadn’t killed yourself.

William took a folded sheet of paper out of his pocket to use as his sorting surface. Before William emptied the bankie on top of the page, Chas glimpsed the words Why I would make a good sperm donor written across the paper and underlined.

William separated the seed from the bud. “Do you ever hear from Dolly?” he asked.

“Dolly? No, thank God,” said Chas. “Not a word for two, nearly three years. But I expect she’ll turn up like a bad penny. I gave her some money to stay away. It’s probably long since run out.”

“You didn’t get divorced?” asked William.

“Why should I? Divorce is ridiculously expensive. She wanted half of Midden House as well as half our place in town. The cheek of it. My family’s property. Never held a job down in her life. It’s not like we had any children. Having a child would have interfered with her sex life. Trollop. Did she sleep with you too?”

William was a little taken aback, uncertain how to answer in case Chas responded with one of his flurries of anger.

“Chas, you know how she was. It wasn’t just me.”

“I married the local bicycle, you mean.”

“She wasn’t really local,” said William. “She came from the East Coast.”

“Very funny. So you slept with her too? Spare me the details.”

William’s brow furrowed. He hadn’t been planning to share any details. He remained keen to pacify Chas. “The thing is, I have to take what I can get. I’m sexually underutilised.”

Chas laughed, which emboldened William to ask something that was on his mind: “I don’t suppose any of the ladies at your party wears an A-cup?”

“An A-cup? I don’t really think you can afford to be that picky, William.”

“No, I mean, I need a small cup bra. For my anemometer.”

“Ah. Well, you won’t get that size from our fresh-faced lass, Nina. I could check to see whether Dolly left any behind, but she didn’t really go in for bras.”

“No,” said William. “I remember that about her.”