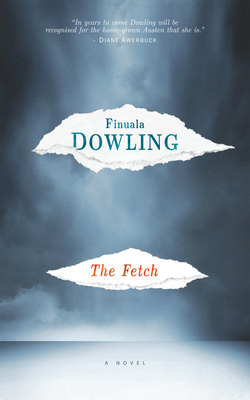

Читать книгу The Fetch - Finuala Dowling - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNina’s life began on the day Chas first invited her to Midden House.

That Friday she came home from work in the same taxi as Fundiswa, who’d been to the doctor in Fish Hoek and who was pleased to see Nina because she needed help with her shopping bags. The taxi driver pulled up close to the sandstone cliff, opposite the board saying SLANGKOP. After that they were on their own.

Although the Slangkop sign was clear – bold black writing on a white background – there was no immediate evidence of human settlement. You had to look closely to see where the untarred access road began its plunge through the reeds and milkwoods to the sea.

They waited in the overgrown roadside ditch, up against the cliff, until it was safe to cross the scenic drive. Someone, long ago, had etched a year – 1920 – at eye-level on the stone of the cutting. In that year, or soon after, Nina thought, construction must have started on Midden House, Slangkop’s only architectural jewel.

She traced the numerals. Whose fingers reached out from history to touch hers? One of the convicts who built the road, perhaps, boldly marking time, as if to say: “I was here; what I did was important; think of me.”

They had only just started down the track towards the sea when a vehicle hooted at them. It was a pert little bakery van with a fantasy iced-cake decal on its side panel. They were blocking its progress. To allow it to pass they had to step backward into the fynbos. Their action disturbed a sunbird in a sugarbush: he ceased his tseep-tseep and flew away. The women stood for a moment among the sea roses and fragrant buchu, watching the bakery van making its perilous way down to the plateau.

There was only one place it could be going.

“It must be his birthday,” said Nina.

“Who does he think he is, having a cake delivered? I call that very pretentious,” said Fundiswa. “And here are the two of us, relegated to the bladdy ditch like his vassals! I’ll have to wear my earplugs again tonight. Honestly, and I moved to this place to get some peace and quiet!”

Nina didn’t mind having to stand among the rushes, her sandals choked with hot dust, to give Chas’s gateau right of way.

“Just imagine being Chas,” she said. “Or one of his friends.”

Friendship with Chas! The thought thrilled her then. Chas was life. Take me there, thought Nina. Let it begin.

Chas entertained every weekend. Mondays to Thursdays were quiet at Slangkop – only the gulls, the wind and the Atlantic stood between the small community and silence. The shutters of Midden House were closed. Emmanuel, the factotum of the house, clipped, watered and weeded.

But on Fridays Chas arrived in his Karmann Ghia with its roaring VW engine. From her small upstairs balcony Nina could see him on a Lilo in the tidal pool, sometimes with a cup and saucer balanced on his tummy. If she took the sandy public pathway, which ran alongside the grounds of Midden House, she could spy on him more closely. Through the gaps in the hedge she’d hear him crying “Welcome to my bolthole!” to guests as they streamed down to join him in the pool.

“They say he used to be married,” said Nina. “Or is still, but they’re separated. I see a lot of women there, but I don’t think he has a girlfriend.”

Fundiswa had been concentrating on her feet, making her way gingerly down the stony track, but Nina’s barely disguised longings irritated her into speech.

“If you’re searching for a father for your babies, you’re looking in the wrong direction. Wethu! That Chas, I’m telling you he is a man-whore. You’re wasting your time if you think you’re going to find a suitable husband in this backwater. How old are you, if I may ask?”

By now they’d reached the highest of Slangkop’s properties, the hermit’s cottage. It was almost completely hidden in a milkwood grove, though its weather vane, a cherub blowing on a vuvuzela, was visible above the canopy. Nina thought of William as a hermit because he lived alone and had few visitors, though the same could be said of her, and of Fundiswa, for that matter. The difference was, she supposed, that she and Fundiswa were normal, whereas William was not.

“I’m twenty-eight,” she replied. “I have sometimes wondered about doing it through a sperm donor.”

It was the kind of silly thing she said in those days in order to get people to laugh. Her throwaway remark made it sound as though the traditional method of baby-making was at her disposal, but that she was opting for a male-free version. The truth was rather sadder. Twice in her life she had come close to having sex, but at the moment of penetration she’d run away because it felt sore and like an odd thing to be doing.

“A baby in a syringe!” Fundiswa put her shopping bags down and laughed. Nina would be in trouble with her doctor, she said, for putting an already at-risk patient in danger of a heart attack.

“Do you know that in Geneva they’ve got a shortage of donors because the men aren’t allowed to remain anonymous?”

Fundiswa liked to bring up Geneva. It made her feel important to refer to the time she’d spent with the World Health Organization. And it made Nina feel important to know someone who’d been someone at the WHO. They rested for a moment in the shade offered by the hermit’s milkwoods and talked about Swiss sperm.

At that elevation they had a clear view of the sea. It was a sweltering February afternoon and Nina looked longingly at the turquoise pools that shone out amid the dark kelp beds. Between the rocky gullies that formed most of this coastline, there were patches of the whitest beach sand, centuries worth of finely ground shells. It was a pity the water was so cold, thought Nina. She seldom went in beyond her ankles, but she’d seen Chas dive in and come up shaking his wet hair.

Her romantic reverie was interrupted by the squawking of the hermit’s quail.

“That damn bird,” said Fundiswa. “It never stops. Another thing to bring up at the meeting. What a weirdo. He never greets, he stinks of dagga and now he’s keeping exotic poultry.”

They continued their descent, welcoming the cool air on their faces as they reached sea level.

Midden House stood on the seafront. The flats where Fundiswa and Nina lived faced the service entrance of the Fawkes family residence. The bakery van was parked in Chas’s driveway behind several other cars. The baker was still at her steering wheel; she was holding her cellphone to her ear. They could see why she hadn’t delivered the cake yet. A large male baboon sat atop one of Chas’s gateposts, apparently monitoring her.

“Oh dear, it’s the outcast again,” said Nina.

When she saw the two women, the baker reversed a little and wound her window down.

“How’m I supposed to deliver this gentleman’s cake? The moment I bring it out of the van, this one here’ll think it’s his bloody birthday.” She gestured in the direction of the baboon.

The baboon looked away towards the sea, as though pretending not to overhear their discussion.

“I keep phoning this Chaz guy, but he doesn’t answer. I even hooted, but no one comes out.”

“They’re probably round the front,” said Fundiswa.

“Actually his name is Chas, you pronounce it ‘Chase’,” said Nina.

“Hello, hello, hello!” Chas stepped off his back stoep and approached them. He was wearing a pair of cargo shorts and an unbuttoned shirt. His fine brown hair, almost girlish in length, flowed around his shoulders. “Is this my cake? Why don’t you bring it inside?”

The baker pointed up at the baboon.

Immediately, Chas called for assistance: “Emmanuel! Baboon!”

Emmanuel appeared with a wire broom, wielding it like a knobkerrie. With his thick-lensed, black-rimmed spectacles and gangly physique, Emmanuel was an unlikely hero. But he walked purposefully towards the primate, swinging his arms and grunting as though he were a male baboon himself. Chas too adopted a simian demeanour.

Reluctantly, the baboon dismounted the gatepost. They watched it make its way slowly up the track towards the mountain, like an admonished schoolboy. Nina felt a pang of pity as she watched his knuckled gait. He was going away but as he had nowhere to go to, no troop or family, he could only pretend to be on his way somewhere.

The baker opened the back of her van and brought out a tray bearing Chas’s birthday cake. We love you, Chas, it said in toffee-coloured piping on the dark chocolate icing.

“It’s sweet of your mother to order you a cake like that,” said Fundiswa.

“Oh, no, I ordered it,” said Chas. “One’s friends need a little prompting every now and then. Let me take that,” he added, relieving the baker of the cake and heading back towards the house.

“If you could just sign the invoice,” said the baker. “That’ll be three hundred and fifty rand, including the delivery.”

“So much! Do you take credit cards?” asked Chas.

“No, we’re strictly cash on delivery, I’m afraid.”

“Oh dear,” said Chas. “I don’t have a sou on me. But I can’t have a birthday without a cake. Seems a bit embarrassing. I’ll have to ask my guests if they have any cash. Unless, of course … ”

He looked at Fundiswa and then at Nina.

Fundiswa stared at him as if she would like to grind him to a fine powder and offer him as snuff to a passing sangoma.

“I’ll pay,” said Nina, putting down Fundiswa’s shopping so that she could open her purse. Let this god have his cake and eat it, she thought.

She regretted her generosity immediately. Would he pay her back? She hoped he didn’t think that she had money to burn. It was just that making one big withdrawal rather than several little ones saved on bank charges.

Chas smiled at her. “Why, thank you, Nora,” he said.

“Nina. Her name is Nina,” said Fundiswa.

“I do apologise. You’re the very opposite of a Nora.” Chas took her in from head to toe, lingering slightly when he reached her thick-soled fisherman’s sandals.

“I’ve got some books for Emmanuel,” Nina said quickly, in order to deflect his attention from her dusty feet.

“King-i Richard?” asked Emmanuel, leaning his broom against the gatepost so that he could take the books with both hands. He added an -i suffix randomly to the few English words he knew. “Dankie, Miss Ni-ni.”

“And another one about Namibia.”

In addition to pictorial biographies of ancient royalty, Emmanuel liked big, full-colour ethnographic studies of Namibia. In an odd mixture of sound effects, sign language and English and Afrikaans, he would describe to Nina the books he wanted. He read with difficulty, blaming his poor eyesight, but loved books for their own sake, holding them with a kind of helpless reverence in his long, slender hands.

“What’s keeping you, Chas? The drinks are flowing like glue!” A female guest posed at the kitchen door with one hand on her slim hip; she wore only a flimsy sarong, knotted tightly at her cleavage.

“I must get back,” said Chas. “However can I thank you?”

“It’s nothing really. I enjoy helping Emmanuel with his interests. So few people use the library as a library any more – they just come in to use the internet.”

“Not for the books, darling, for the cake. However can I repay you?”

“You can just repay her by repaying her, is what I would suggest,” said Fundiswa. “And you could invite her round for some of that birthday cake.”

“Of course! An excellent idea! Come along later, after the meeting. I feel I should pop in and do my civic duty. I’ll see you two there, I presume? But afterwards, why don’t both of you come and join the party?”

“Thank you. I’d love to. If you’re sure … ?” said Nina.

“Count me out,” said Fundiswa. “My partying days are long over. But, please, keep the noise down. I think you sometimes forget that there are people living behind you.”

They looked up at the duplex, which the architect had designed with only economy in mind: low pitched, extensively glassed. No wood, stone or even a touch of greenery to soften the blank and now somewhat stained whitewash.

“It’s your landlord’s fault for building that monstrosity right on the boundary line,” said Chas. The sharpness was momentary, then he was all bonhomie again: “I hope you like sangria, Nina. Just the thing for a hot February evening.”

“Are you happy now that I’ve got you your invitation to Midden House?” asked Fundiswa as they watched Chas and Emmanuel make their way through the back gate of Midden House, the one triumphantly bearing his birthday cake, the other carefully examining the covers of his library books.

“Thank you,” said Nina as they turned to cross Cockle Way. “But, of course, I’m feeling nervous now. All those artistic people from the City Bowl. I suppose I could wear my white dress with the red piping – the one you said you liked.”

“It’s a nice dress; it’s becoming. Go along. But don’t get your hopes up. Later, when you’re my age, you’ll know how disappointing a party can be.”

Fundiswa used her remote to open the gate. Nina helped her carry her groceries inside before climbing the stairs to her own flat. She was nearly at the top when Fundiswa called out: “By the way, I’m planning to start a jogging regime tomorrow. In fact, it was my new year’s resolution, so I’m a month late. Why don’t you come with me?”

“I don’t jog. I’ve never jogged,” said Nina, by way of an excuse.

“Come on, what’s the worst that could happen? We might get fit! I need some company, and I can assure you that it won’t be very strenuous.”

It wasn’t the exercise that Nina was afraid of, but the prospect of people staring at her as she puffed along. Still, she would love to be fitter, slimmer. If there were any onlookers, they’d probably find Fundiswa more of a spectacle. She agreed to jog.

Nina kicked off her dusty sandals and opened the sliding doors onto her balcony to let out the accumulated stuffiness of the day. The incoming tide brought in a strong smell of sea and kelp. She breathed in the clean atmosphere. All day long she worked in a pall of farts: library borrowers seemed to experience an immediate relaxing of their bowels as they perused the shelves or read the free newspapers.

When she had begun studying for her diploma, she’d thought that she would end up working with scholarly or at least thoughtful people. But she had ended up in a suburban library that mostly serviced pensioners who fought with one another over whose turn it was to take out Foyle’s War. The staff was also kept busy by children from three or four local schools. Teachers set identical projects with identical deadlines so that there was always a crisis about “Volcanoes” or “Robben Island”. Once a week the librarians were supposed to get together for a book discussion, but it turned out that two of Nina’s colleagues didn’t like reading or perhaps struggled to read. Her career had more in common with police work or refereeing. She had to stop patrons from stealing the Bob Marley biographies, bringing recording devices into the music section and, every now and then, photocopying whole books.

She liked the detail of classification, though. Only the other day, for example, they had received a batch of CDs from the provincial library, classified alphabetically rather than according to the Dewey decimal system. Absurd, thought Nina. You couldn’t have books on Beethoven shelved at 780.92 and then some music by Beethoven (but not all) shelved at Beet. It gave her pleasure to fix that.

While she reclassified Beethoven, Nina dreamt of places where laughter and champagne glasses tinkled, and intelligent people spoke about fascinating things. But now that just such an event was so close and so real (she’d even paid for the cake), she felt apprehensive. How much pleasanter and easier to stay at Cockle Place, not to have to stand on tiptoe to open the latch of someone else’s gate; not to have to walk up the garden path in full view of other, more legitimate guests; not to have to introduce herself, account for her existence.

Yes, she wanted to attend a party at Midden House, but perhaps not this party, not today. Another time, when she was less tongue-tied, when experience had waved its wand, transforming her mousy words into dapper footmen in shiny livery.

There wouldn’t be another chance, though, she knew that. And while it was possible that somewhere down the line she would develop a little more confidence, that wasn’t going to happen by staying home alone. She tried to jolly herself into a positive frame of mind. Already she was guaranteed the cachet of arriving late, since she had to attend the community forum meeting first. She might even walk from the meeting to the party with Chas and his mother.

Thank heavens she had a suitable dress, clean and ironed. Perhaps it would speak for her and say: “The wearer of this dress is modest but open to suggestion. She reads a lot and has an interest in history.” This much could be said by a soft peasant neckline and a little red piping around the hems.

Nina stood on her balcony looking down, as if studying Chas’s Edwardian seaside home might teach her to enter it like a native. But there was no way to fix Midden House in one’s gaze. Everything seemed to spill out of it. The painted green shutters were flung open; guests milled on the stoeps that wrapped around both floors. Nina could hear voices trilling up from the front steps and the lawn where Chas’s mother sometimes played croquet; even a splash and a shriek from the tidal pool below. Clearly, the party had already begun.

She showered and put her clothes on in her usual modest way, not looking in the mirror until she was covered, only one section permitted to be naked at a time, like solving a Rubik’s cube. She could not see herself undressed without hearing the ex-boyfriend voices, the one who had said: “Now I know what they mean by Rubenesque!” Or the crueller one’s observation: “You’re built for comfort.” And then they wondered why she ran away. It was all part of the same conundrum – her weight and her fear of sex. She ate chocolate not only to insulate herself against male regard but also because she was frustrated by the lack of it.

It was still too early to set off. To pass the time, Nina sat on her tiny balcony looking through her Slangkop file. Perhaps here, among the newspaper clippings she’d collected, there was something that would help her make conversation tonight. Not the magazine article on Neville and Sharon’s caravan park, and not the City of Cape Town’s fifteen-page conservation report on this “relatively undeveloped coastal terrace” – no one wanted a guest who spouted gobbets of tourism. What might help her were Chas’s articles and reviews, the photos of him at society events.

“If you like my figure so much, why don’t you visit me?”

It was Fundiswa’s voice, floating straight up to Nina’s balcony. Fundiswa must be speaking to someone on the phone. Nina dared not even turn a page now, for fear Fundiswa would know she was eavesdropping.

“Before, your excuse used to be that everyone would see you if you visited me. Too public. So I move to this completely clandestine place and now you say it’s too far away. You could come and spend the night here. Tell them you’re going on retreat.”

Strange, Nina thought, that a woman of Fundiswa’s age should be speaking so flirtatiously. Didn’t you firmly shut the door on that aspect of life once you turned sixty? Apparently not.

“Might die on top of me! How can you say such a thing! I don’t like the way you assume we’ll be in the missionary position.”

Fundiswa was laughing at her own wit, in a way that suggested the other person was laughing too. The joke seemed to set matters right between them, because Fundiswa ceased to be confrontational.

“Alright, Bishop,” she said. “Tell me all about your week.”

Nina heard nothing more. Perhaps Bishop had a lot to say about his week, or perhaps Fundiswa had moved inside again. Nina could pull her chair in without worrying that the hard metal scrape would betray her presence.

She turned her attention back to the society pictures of Chas in her file. He was a person the camera loved. It caught his dimpled cheek and his large eyes that seemed all pupil. His expression was merry, inviting. Such a well-made man: not too tall, neither muscle-bound nor flabby, but finely knit and compact. And then there was always that hair, framing his face like a girl’s, except that the face itself was so evidently a man’s: high-browed, the lines of jaw and nose unequivocal.

It was enough just to be allowed to look at someone like Chas, she told herself. Except that, of course, it wasn’t. It flicked a switch; it turned on a fluorescent light in the empty room of one’s own emotional and sexual life. See, said the light, you have none of that beauty here. You have only this poorly furnished room.