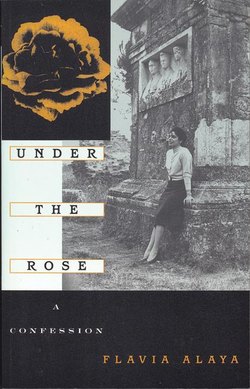

Читать книгу Under the Rose - Flavia Alaya - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

This book has had a long and layered history. My best enemies tried to discourage me from writing it. My best friends begged me to make it a novel. And in some sense I have, not just to please them, but because I could see no way to tell the story without all the color it came to me in as I wrote it. I did not understand why, unless we mistrust the very gorgeousness of truth, a true story need be any more dull or evasive or lame than a fictional one.

This was a problem for readers who thought, and may still think, that the stylistic boundary between true and fictional narrative should be wide and well-policed. Maybe a distaste for my style went with a disdain for my morals, with the result that when a late-draft manuscript was circulated some time ago a certain distinguished editor remarked, in the same breath, that she liked neither style nor person, the one being “too ornate” and the other “not nice people.”

I believe—or, more to the point, I believed—she was not alone in thinking so. I had already been working on the book for too many years, too many years pocked with too much anguish, to make her judgment bearable. I made a halfhearted effort at getting it published after that, followed for a time by no effort at all.

Because I eventually saw a beautiful symmetry (simultaneously beautiful and true) between trying to make a life and trying to make the book about making it, I tell some of this tale of lost heart at the end of the book. I recall it here only to spotlight a certain sea change in the publishing universe as the book finally enters print. Not because the editor’s judgment I describe will never be passed again—no doubt it will. But because I think there is a greater friendliness now toward my style and my story, a greater willingness generally to accommodate the voices of women and of Italian Americans—attitudes toward both of whom, I believe, were unconsciously coded into that denigrating put-down.

For me these voices happen to share a common chord, a common vocal idiom, which the opera titles of my parts are meant to both signal and amplify. But I have been a long time giving myself permission to be “ornate,” which means to me also to be operatic, in some real sense excessive, to be romantic (and italic) in both language and emotion. I have needed a lot of help from other women, and from other Italian American writers. Why should I be surprised it is a permission even slower in coming from the mainstream world of publishing, or that small presses should have to push the envelope?

I am no less grateful for it. Publisher Florence Howe of The Feminist Press has done tremendous service to publishing in many ways, but perhaps none more so than in candidly admitting how late the Press came to printing and reprinting Italian American women, or how long she herself took to hear the resonance of voices like those of Helen Barolini and Dorothy Bryant and Tina De Rosa. Whether or not the world thanks her for publishing me, she has published them.

But romance, even Italianate romance, may be one thing and scandalmongering another. Even you may think my story about “not nice people.” Or because it is true, too too true, about someone who has rendered herself “not nice” by the very act of telling it. Bad enough to commit the sins I committed. Worse the effrontery of making them public. It seems always to come back to this: If only it were fiction! Then I could write it and you could read it and we could all go see it, or its equivalent, at the movies (or the Met) and still be “nice people.” Quite nice, in fact.

But I could no more make it fiction than I could live another life. Much has been said about “transgression” and its role in the discourse of feminism, but even feminists are conflicted on the point. Some will need to cast me as a kind of victim, a whistleblower on the hypocrisy of “concubinage” and the myth of Catholic celibacy, insisting the book ask how the Church could possibly promote a higher standard of moral, indeed of sexual responsibility, and continue to allow such wrong to be done to women. Or to men. And they are right. It’s what the book is meant to ask. Or I should say, was meant to, before telling my life had performed the strange alchemy of transforming it, and I was more deeply self-identified as a Catholic than I frankly am now, and cared more that such hypocrisy was itself scandal to the Church.

Which is not to say that I care less now about women (and other men) who live in long-term relationships with Catholic priests. I care, and care deeply. I care about those who love priests and are forced to feel ashamed, to experience their love as “sin.” And I care about the priests, not those who prolong such relationships out of a certain relish for the exploitative power that is inevitably part of them, but those who simply cannot bring themselves to leave their vocations, even for love. I care, and I believe the Catholic Church, which has to answer for all these ethically compromised relationships, should care, because everyone should.

But I have to confess a more unregenerate transgression. I have to confess that I am still grateful for the passion—and the freedom—that the Church’s hypocrite secrecy made possible for me. “We cannot all be white bread,” said the Wyf of Bath—as true a woman as ever man made—when she told us about seducing and eventually marrying a cleric, and so spoiling a priest. In my case I don’t take all the credit for the seduction (and even with the Wyf of Bath it worked both ways), but I know I can’t somehow turn brown bread into white by some abracadabra of moral transubstantiation afterward, and I don’t want to try.

I have said freedom as well as passion, and I mean to underscore it. Freedom: personal and political. And freedom for Harry Browne as well as for me. I can’t tell you Harry Browne would have approved my pronouncing this insight on his behalf, especially in print, but I can tell you what I most deeply believe: that it was and is as true an insight for him as it was and is for me. It is one of the things this book is about. It is one of the most vexing and irreducible things it is about.

Others, even other feminists, perhaps completely understanding that as a writer I could not choose but write this (and having written it, want it to be read), may still think it hollow of me to protest my doing and writing it all in the name of freedom, if, in the end, it is a freedom still defined by love. Love for a man, a man who in this case also dominates my narrative. Two men, in fact, the two “fathers” of whom I beg forgiveness in my dedicatory words. I have no excuses for this. Our lives are what they are. Mine was defined by love, and still is. Almost unbearably so. It has been, in one form or another, from my infancy.

Perhaps I am too hopelessly, too operatically, too radically Italian in this. I will never forget the time my sister-in-law the Italian feminist came back from a meeting of Italian feminists recounting an impassioned discussion on just such a theme: “Ma, perche li amiamo? Perche continuiamo ad amarli?—“Why do we love them? Why do we go on loving them?” I have never heard the question put quite this way among American feminists, who I think might be vaguely embarrassed to expose, not their libidos, but their hearts in this way. Let me dare to think that perhaps my book, since it is about love as well as sex, is the more Italian (and Italian American) for this. Perhaps also because it is so centrally about the Church, the patriarchal yet motherly Church, the Church of love bodily and spiritual sitting in the center of that culture, geographically and in every way. Also because it is about how an Italian American woman navigates such conflicted territory here, here in one of the hearts of the diaspora, where Catholic spirituality is no better represented than among Irish Catholics. Like Harry Browne.

And finally because, like so much Italian opera, it is about love and politics—the politics of personal love and the politics of collective freedom. It will become obvious to any reader that I believe we live our lives in an ecology of relationships, including historical ones: that this is a definition of politics. That (borrowing from philosopher Emmanuel Levinas) the politics of freedom begins with accepting even the self as impossible without responsibility toward what we perceive as irreducibly different. But that we must feel this at the level of emotion as well as of mind.

And so let me also dare invoke the spirits of two women, Olive Schreiner and Simone de Beauvoir—deeply political women and writers and lovers, neither of them Italian yet both of them my patron saints—as I say this to my readers: I have written my book. I let it go, with all its flaws, into your hands, into your minds and hearts. I have been able to invent no better way to tell my story of spiritual and political freedom, of being a woman between many genders, of being an Italian between many cultures, than to be true to the experience of my own life.