Читать книгу Under the Rose - Flavia Alaya - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAcknowledgments

A single life is inevitably a compendium of other people’s lives, and the history of this book about me is also a history of other people.

Not long after Harry Browne died in 1980, I was approached by a television producer who said I had a good story. Her version was not quite the story I wanted to tell, and so I was determined to tell it myself, but it was then an episode rather than a life—the “Harry book”—and for many years that’s what it remained. Thanks to Patrick O’Connor and Charlotte Sheedy, a few sample chapters got me a Macmillan contract. Soon the publishing dragons came and swallowed up whole houses, spewing out better books than mine. Cynthia Merman, then at Atheneum, stood by me, even as they roared and spewed. Joan Brookbank, my new agent, rafted me to safety on the mighty flood that followed. In those tough middle years, the late, magnificent Ellen Moers, pioneering feminist critic and midwife of difficult literary births, inspired me to go on writing, almost literally handing me when she died to her brilliant friend, writer Esther (E. M.) Broner. I bless all these wonderful people for treating me not like a writer-in-the-making, but like a writer.

As the manuscript circulated, and word got out about the story, I don’t like to think what went on behind the cupped hands of people who thought it too naughty for their imprint. Rumors abounded of characters like Harry Browne being written into soap operas. I have had an absolutely unbased paranoid fantasy that the New York Archdiocese had a role in thwarting the book’s publication at some point. But when a spate of new books appeared in the early 1990s about priests and women, when Annie Murphy became a celebrity, calling a scoundrel a scoundrel and proud of it, it seemed to a lot of people that “it” had been done, whatever “it” was. My contract had already died, a blessed death, as I see it now. For just as the TV producer’s story was not my story so neither was Annie Murphy’s or any of the other variant voices of women with priests that enjoyed their brief succès de scandale at the time.

Had it not been for Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way (because it is clearly the artist’s way to have a certain necessary chutzpah) I would not have approached The Feminist Press. Had it not been for Florence Howe and The Feminist Press’s Cross-Cultural Memoir Series, the story might never have been expanded into the fuller “life” it is now. If not for my editor, Jean Casella, it would never have become a “life” that I feel even tremulously proud to have written. I have told her that no one reading me has ever been so intuitive about what I intended to say and do, that when she could not see through my verbal impasses she always, always, inspired me to write my way out of them. Now I get to tell her in print. And to apologize for the weaknesses in me that in the end set the limit to how much better a book she could make it. As for the other Press staff, I thank them for all the care, the meticulousness and beauty, of their work, and for being part of a mission to understand women’s writing, as well as to keep it alive and in print.

Ramapo College, its administrators and sabbatical and research committees, were an inevitable part of the process, giving me small amounts of released time—never enough of course! But they meant well and I am grateful. And I don’t know who I would be if it weren’t for the intellectual freedom to be who I am and have been there, or the wonderful colleagues I have lived with and loved in the School of Social Science over the years, especially Patricia Hunt-Perry, friend and soulmate across a single office divider wall. It was she who put my story up with much better peoples’ in a lecture series called “My Life is My Message” in 1996, and created a turning point in my sense of claim to a life worth having lived, let alone having written. This was clinched by a grant that same year from the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation to spend a month of blissful Vermont time writing, and being well-fed and lionized, at the Vermont Studio Center. They have a lot to answer for.

I want to thank the many people who, having loved Harry Browne and vividly remembered the West Side scene in the sixties when I interviewed them in the eighties, launched heartily into stories that have enriched the book, especially Dr. Marvin Belsky, Mike Coffey, Monsignor Jack Egan, Father Tom Farrelly, Fred Johnson, Father Phil Murnion, and the delicious and incomparable Esta Kransdorf (Armstrong). Esta died suddenly in 1995, a shock that darkened a host of lives, and lost me my wisest and most discerning reader.

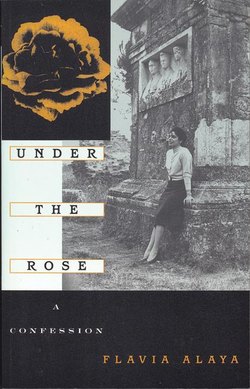

Then there are my three children, Harry, Chris, and Nina, who jestingly refer to themselves as “spawn of Satan”—or the funniest and witchiest of them does, and cracks up the other two. Also their wonderful partners, Imelda, Rebecca, and Carl, who have stood by them as they stood by me. I still don’t get how they did it, all of them. How they not only let me go on writing like this, for what seems decades, but rooted for me, boasted about me, casting the movie at least three different times. Thanks to the rest of my family, especially my darling sister Ann (whose poignant roses illuminate these pages), for bearing all this self-indulgent revelation—so far as they have borne it. I think they know the worst is yet to come. My husband Sandy does too, and it seems almost presumptuous of me to say thanks for a love that has already survived tests of trust and courage that would wither lesser men, and will have to survive more.

Finally, unutterable gratitude to all the people who have ever loved me in my life, my parents, my relatives, here, and there, my wonderful, devoted students, my friends, those I still have and those I have lost. And to all the artists and writers who have ever made it possible for me to think of myself as an artist and a writer.