Читать книгу The Vagabond - Frank Rautenbach - Страница 12

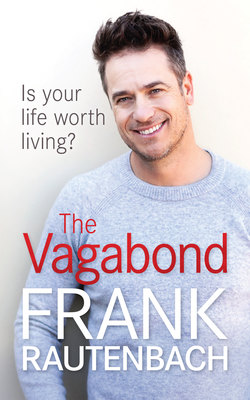

THE VAGABOND

ОглавлениеMy mother withheld most of my father’s challenges from us kids. She wanted us to lead as normal lives as possible under the circumstances. It was only after I had heard my father tell his version of the story that I realised how close we had come to losing him.

Two days after my father’s heart operation I did what I normally did: hang out at my girlfriend’s house. It was the Friday afternoon, 13 October. The phone rang. It was for me. It was my friend Miles.

He was super excited, wanting to know if I was keen to join him and another mutual friend, Eyeball, on a great adventure. (Eyeball got his nickname because his eyelid moved up and down, in sync with his jaw, when he chewed.)

Miles’s mother had organised for us to go sailing from East London to Port Alfred overnight, a distance of about 130 kilometres. The plan was to sail there and surf in Port Alfred the next day. Eyeball’s mother would pick us up and take us back to East London, in time for his father’s birthday on 14 October.

I thought about it for a half second.

‘I am in! When are we leaving?’

‘In an hour; see you at the harbour.’

I grabbed my helmet and shouted back to my girlfriend as I was leaving.

‘I am going sailing with Eyeball and Miles to Port Alfred!’

I got on my bike and rode home as fast as I could. As I ran into the house, I asked my grandmother if I could stay at Miles’s house for a surfing weekend. It was not unusual for me to do this. Plus, my grandmother knew Miles well. It was fine, she said. Just be safe.

I didn’t breathe a word about the sailing.

I grabbed my wetsuits, board, towels and blue-and-pink parka. Miles and Eyeball had already arrived when I rolled in on my bike. There seemed to be a little tension between Miles and his parents, but it seemed to get resolved fast.

Eyeball’s mom had dropped him off. She waved goodbye. ‘See you guys in Port Alfred.’

An impressive double-hull catamaran was moored near where Miles and his parents were standing. I thought, ‘Wow! This is going to be amazing!’

I walked up and asked, ‘Hey bru which one is our boat?’ An older-looking gentleman waved from the other side of the catamaran.

‘Come aboard!’ He was the captain we’d be sailing with. He looked like an old-time sailor – white hair and beard. Only his yacht was moored next to the catamaran. She was about 18 metres long and the stern deck looked like a messy tool shed.

Her hull was navy-blue. Her name, painted in white – The Vagabond.

She wasn’t perfect, but she’d do for our adventure. The only complaint I had was the smell; everything on the boat smelt liked diesel fuel and fish.We got settled in – and learned from the captain that we’d be using the boat’s motor to get out of the harbour. Once we got into the open ocean, we’d set the sail on course to Port Alfred.

We waved at Miles’s parents as we left the shore. The closer we got to the open ocean, the more we felt the swell as it came rolling in. Full of excitement and energy, we made our way to the bow. We held onto the pulpit and lifeline dearly, hollering and riding those waves as if they were bucking broncos.

The sun was starting to set as we rounded the harbour wall. The swell was getting bigger. We were excited about this; it meant good surf the next day. There was a northeasterly blowing, which would be helping us down the coast. None of us had sailed before, but we were keen to learn. The captain was showing us the ropes as the wind filled the mainsail and we were off on our adventure.

It had been a beautiful, sunny day in East London – until the sun went down. We were not even 10 kilometres out when we noticed the wind picking up. Every gust blowing harder and stronger than the previous one, until the ocean was whipped up into a frenzy.

Angry waves bashed into our yacht and, before we knew it, we were caught in a severe storm.

The captain stayed calm. He commanded Miles and me to strike the mainsail. As we started turning the crank to bring it down, we heard a massive ripping sound. We both looked up and realised the sail must’ve got caught against something sharp. Then the wind just ripped it further.

‘Be careful!’ the captain shouted.

We had no idea what we were doing, so we kept cranking until the sail was fully down. In a moment, we had lost our mainsail. The boat was tossed around violently as we battled to secure ourselves on the deck.

We didn’t think to tie the sail down onto the boom.

Another wave hit us. Eyeball screamed. We looked up and we saw him holding his wrist. The wind had caught the unsecured sail and sent the boom jibing across the deck, missing his face by a hair’s breadth. It knocked his diving watch right off his wrist and into the ocean. Eyeball was in shock.

The captain kept shouting above the noise of the storm, telling us he would be using the motor to get us back to the harbour. It spluttered and coughed as it sprang to life. The boat slowly turned into the face of the storm. The Vagabond fought bravely through the oncoming swell. The motor strained to keep her moving forward. We’d hardly turned around when we heard a loud clunk. The captain stuck his head in the engine room. A few minutes later, he came back up. The motor had seized.

‘Not to worry,’ he said. ‘We’ll send out a mayday distress call to the harbour.’

The wind and waves kept driving us deeper into the ocean, until we could barely see the city lights. We were only a few miles from the harbour. Why was no one picking up our distress call?

The two-way radio wasn’t working.

Eyeball’s sea legs didn’t last long. He was doubled over the side of the boat, emptying his stomach. Miles stuck by his side, making sure he didn’t go overboard. The captain, looking more distressed, told us he was going to try to fix the motor.

And that is where he stayed all night.

The captain gave me the job of ‘steering’ the yacht. I tried my best to point the bow in the direction that the wind was blowing. I had no idea what I was doing, or if I was even doing anything to affect the direction that we were moving in. The wind gusts kept getting more violent. Miles and I still hadn’t secured the mainsail properly to the boom, and the wind kept unfurling it and chasing it up the mast.

This, in turn, would cause the boom to jibe unexpectedly and dangerously across the deck. We also hadn’t secured ‘the preventer’. We didn’t know what ‘the preventer’ was, let alone how to fasten it. (The preventer is a line that stops the boom from jibing across the deck if the wind shifts or boat rolls.)

The captain came up on the deck to check our position and noticed the unsecured sail.

He shouted at Miles and a very sick Eyeball to tie down the sail and secure that preventer thing. At least Miles had the sense to ask for harnesses, but the captain didn’t have any.

Cautiously, they stumbled across the deck to secure the sail. As they got there, another violent gust of wind caught it. The boom jibed straight in their direction. They instinctively tried to stop it, but they were lifted right off their feet instead. They grabbed onto the sail, the various tangled ropes attached to the boom, and hung on for dear life. The boat rolled. The boom jibed … and cleared the gunwale. It rolled so far that their legs dipped into the ocean. Rolling back, the boom swung across the deck. They let go and fell onto the deck, shaking with fear. Knowing that, had they slipped off the boom, it would’ve been the last we’d see either of them.

They still had a job to do, securing down the mythical preventer and tying down the sail.

Miles and Eyeball found me hanging onto the helm where I cluelessly tried to figure out how to steer the yacht. Eyeball’s face was the picture of fear. He started crying. My head was spinning from the never-ending rolling and pitching. I never felt sick, but I was beyond exhausted.

What should we do, they asked. I said, ‘Nothing. There’s nothing we can do.’

I was an old hand at coping with traumatic events by learning to shut down my fear.

Miles was furious. ‘You don’t care about anyone! You selfish Dutchman!’

I didn’t say anything. I didn’t know what to say.

I couldn’t provide them with any assurance that things would be okay. I didn’t know how else to deal with the stress of our predicament and the trauma they were experiencing.

I had what could be called ‘stupid peace’. The kind of peace that comes from naiveté. I was too young to die. Surely we just needed to wait out the storm and everything would work out. I had no idea of the grave danger we were in.

The east coast of South Africa is a notorious coastline. For hundreds of years, it has been a graveyard for ships of all sizes. Violent storms, massive waves, deep water, treacherous currents and rocky reefs can suddenly create conditions that have seen the end of many a sailor.

Miles started to calm down when he figured out that there was some logic to my thinking. He said he was hungry and made his way to the galley. He found some pork sausages and decided to fry them up. They smelled really bad, getting worse as he cooked them. The pungent smell of the oily pork sausages and the constant smell of diesel and fish didn’t help his cause. The exercise was near-impossible in the constant rolling and pitching. He took one bite of those semi-cooked porkies and that was the end of it.

He came flying up onto the deck and doubled over the rail, feeding the fish, as he heaved away.

It was way past midnight. The wind was relentless, driving the yacht further into the open ocean and down the coast. Waves kept battering us from all sides, sending shuddering shocks through our bodies every time a big one hit. I couldn’t take it any more. My head kept spinning and my body ached from the beating. I had not eaten anything since lunchtime the day before.

I was exhausted, so I stumbled my way to the cabin in the bow of the boat, looking for a place to sleep. I lay down on a green tarpaulin that lay on the cabin deck. I was desperate for my head to stop spinning. It didn’t help matters that, every time the boat rolled, I could see clouds through the porthole. When it rolled back, I would see the water. I feared that the boat would turn turtle. I eventually passed out.

When I woke in the morning, hours later, there was no movement, like the yacht was stranded on dry land. Feeling disorientated, I made way to the deck to see where the others were.

It was overcast. There was not a breath of wind. I couldn’t see land anywhere. There was just water all around us. The ocean was a weird, green colour, glassy like a mirror and completely flat. I couldn’t make out the horizon; it had blended into the clouds.

I felt claustrophobic, right in the middle of an open ocean. The eeriness of it all made it feel like we were in some kind of alternate universe. There was no sound. No bashing waves or rushing wind. No traffic sounds or dogs barking; all familiar sounds were absent.

I found Eyeball and Miles sitting on the deck towards the bow of the boat. It seemed like they had forgiven me for ‘not caring’. I asked them if they knew where we were. They told me the captain said we were near Madagascar Reef.

‘What?’ I said it was impossible that we had blown all the way to Madagascar!

They laughed and said the captain told them there was a reef called the Madagascar Reef near a little fishing village we all knew called Hamburg. It is roughly the halfway point between Port Alfred and East London. We had been blown about 80 kilometres down the coast overnight. We had no idea how deep into the open ocean we were.

In the meantime, the captain was still trying to fix the motor.

He had made several futile attempts to contact the port authorities in Port Elizabeth.

That afternoon, the wind started picking up again. It was a southwesterly. The captain told us to brace ourselves. He suspected the calm we had experienced was probably just the result of being caught between two storms.

How right he was.

By early evening, the southwester was howling at gale-force strength. We were now being blown back up the coast. The only difference was that the waves were much bigger.

A massive storm swell from Cape Town had reached us. The yacht felt like a toy boat as it slid down the monstrous faces of the giant swell. By now we had all found our sea legs and no one was getting sick.

At about 11 pm, we heard Eyeball shouting excitedly from the deck that he could see land.

Miles and I went up to the deck to join him. The captain popped his head out of the engine room. Eyeball pointed in the direction of what looked like city lights.

We kept looking and realised it wasn’t land or a city.

It was a massive freighter.

We had been blown into the international shipping lane. The freighter? Heading straight for us. The old man panicked and asked me to get the signal light from a storage box in the galley. I plugged it in. Passing it to the captain, I went down again to turn on the switch.

‘Plug it in! Turn it on!’ the captain shouted. By now, I knew that it was probably not working.

‘It is plugged in and turned on!’

The captain dropped his head.

Yip, it didn’t work.

We all stood on the deck watching this massive ship coming closer and closer. There was nothing we could do. We had no way of steering the yacht out of its way. We were at the mercy of the wind. I didn’t know what to think. What would it be like if this ship hit us? Would they even know? The captain tried the radio, once again, with no luck.

With panicked looks, we kept staring at the foreboding hulk of metal.

Then, suddenly, it dawned on us that it was busy turning and making its way into the open ocean.

We all shouted, ‘It’s turning, it’s turning!’

We never knew whether it changed course because the bridge had seen us or whether it simply followed the course it had been set. It came so close, however, that we could clearly see the roiling wake, as the freighter’s giant propellers churned up the ocean.

Apart from the storm that was now growing stronger, our close encounter with the freighter was more than we could handle, and we decided to bunk down for the night.

None of us slept well that night. The storm kept battering and bashing us back up the coast.

We were all up by sunrise on Sunday, the third day of being out at sea. Significantly, we could see land for the first time in two days. It lifted our spirits slightly.

The ocean had turned an ugly brown colour, with dirty yellow foam whipped around by the wind floating everywhere. The swells were so big that, when we were at the trough of a wave, all we could see was a wall of water in front of us. Then, as we made our way up the back end of these monsters, the water would lift us high above the ocean surface, and hurl us sideways down the face.

Between the three of us, we were trying to steer the boat. Unlike the steering wheel of a car that responds immediately, a yacht’s steering takes a lot longer to respond. We never did manage to straighten the yacht enough to counter us from careening sideways down the swell. Whenever we’d whip the wheel in the other direction, in a few minutes it became obvious that we had completely overcorrected. We were tired. Traumatised. The exchanges between us became very heated – until we spotted what looked like two large rocks sticking out of the ocean.

We called the captain.

His eyes widened immediately, and he grabbed the wheel from us. It was two colossal adult whales. They were side by side. He said they were mating. If the whales felt threatened in any way, they could destroy the yacht, much like two mating elephants might feel about a bolshie 4x4. He desperately tried to steer us away from the mating mammals.

The wind and the waves, however, kept driving us in the direction of their looming bodies. We got so close we could clearly see the barnacles and scuff marks on the sides of their huge bodies.

The tension on the boat was unbearable.

We were moving at a snail’s pace, about 4 to 5 knots. With every excruciating minute that passed, we hoped and prayed. We could barely breathe. It literally felt like we were tiptoeing our way around them.

As the ocean kept hoisting and lowering us, we could see the whales disappearing into the distance. Once we got in the clear, there was a little moment of relief. Until we realised we were still lost at sea.

At lunchtime, I started feeling the first real pangs of hunger. Our food supplies had consisted of a two-litre bottle of Coke and a humble bag of Ghost Pops chips. The captain said there was food in the galley, but all I could find was mouldy brown bread and something that resembled smelly ham. Nonetheless, Miles and Eyeball would join me and lunch would be ham and chip sandwiches. I took my first bite. I gagged as I tasted the mould. But I was too hungry and soldiered on with the eating. Eyeball’s eye twitched slowly as he tried to chomp his way through the mouldy sandwich.

It lightened the mood considerably.

We heard the Captain shouting from the deck. We all went up.

He was shouting and waving at a fishing trawler making its way towards us. It was painted bright white. The crew signalled from the control deck that we should get onto the radio. Finally, the radio made contact. Why in the world we were in the ocean during such a terrible storm, they asked. It had become too rough for them – they were making their way in. Our captain explained. They promised to contact the port authorities in East London to send out a rescue boat.

I started feeling some hope.

We made our way to the centre of the deck. We tied ourselves to the lifeline with pieces of rope and soaked up some of the sunshine that finally broke through. Buoyed by anticipation, we tried to see who could stand the longest without holding on to anything. We were trying to ‘surf’ the yacht, but it turned more into a contest of falling around than anything else.

Later that afternoon, we heard the sound of a small propeller plane. It was flying low and directly towards us. Eyeball and I danced around and waved like crazy. Miles, ever the conscientious one, made the international signal for a boat in distress – slowing and repeatedly raising and lowering his outstretched arms.

Thank God he did, as the pilot would then hopefully identify us as the boat in distress.

The plane passed us.

Then it turned to bank for another flyover. The pilot waved at us the second time.

Apparently, he reported that we were fine and had been suntanning on the deck. He also reported our coordinates to the National Sea Rescue Institute.

Unbeknownst to us, Miles’s and Eyeball’s parents had been desperately looking for someone with a private plane to fly out and search for us. They eventually got hold of my girlfriend’s uncle, who volunteered to fly out and search down the coastline.

The NSRI would set up a search-and-rescue team and send out several vessels to find and retrieve us. The southwesterly had driven us hard through the night and that whole day. We had made a lot of progress back up the coast.

When the NSRI found us, we were about 10 to 15 nautical miles from the East London harbour. It was early evening as they towed us in.

It felt strange being in the calm waters behind the harbour wall again. My mind was still pitching and rolling, even though the hull was cutting gently through the water.

I saw Miles’s father first. He was running along the dock wall as we made our way in, angrily shaking his fist at the captain.

We finally got to our mooring on the eastern dock. We were exhausted, but happy to be back.

When I saw Miles’s mother, I was expecting a big smile of relief and happiness. Instead, she was crying, and her face was the picture of pure anger. Also clearly directed at the captain.

I remember disembarking and standing on solid ground for the first time in three days. It made the pitching and rolling motion in my head even worse. We all stumbled around trying to shake off our sea legs. I was confused by Miles’s parents’ reaction towards the captain.

He seemed like a meek old man who had just survived a terrible ordeal. There was a reporter from the local newspaper. Miles’s mother confronted him and said that they would sue him if he wrote a single word about the incident. This was way too much tension for me to handle. I grabbed my stuff, got on my bike and rode home.

I casually walked in through the front door. My gran asked how the weekend was. I said it was fine, but we didn’t get much surf. I dumped my board in the my room and with everything still swaying about me I stepped into the best shower of my life.

We were all back at school the next day. As I sat at my desk, I could still feel The Vagabond’s pitching and rolling motion in my head. I looked up, and saw Miles and Eyeball. They, too, were battling to sit up straight. Joking about our ordeal on The Vagabond with our classmates, they gave us the usual ribbing one can expect from teenage boys.

Everyone burst out laughing after hearing we had got lost on a boat called The Vagabond.

Miles, Eyeball and I would never really take the time to talk about what had happened to us.

We just kind of moved on. I think we just didn’t want to remember such a traumatic experience. Years later, Miles told me that when he got home that night he went straight to the bathroom to take a shower. He said he just stood there and cried his eyes out for a long time.

In the years that followed, we joked about it, but only in passing.

The most we would say was, ‘Hey, remember The Vagabond?’ Then we would click our tongues and that would be the end of it.

Twelve years later, while we were eating pizza with my parents and Leigh, my wife, I came clean about my adventures on the high seas. PTSD has a way of keeping secrets for a long time. And it would be 26 years before I would find out why Miles’ parents were so upset at the captain when we got back to the dock …