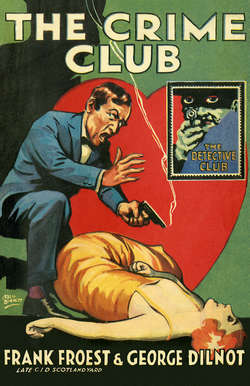

Читать книгу The Crime Club - Frank Froest, David Brawn, Frank Richardson - Страница 7

II THE RED-HAIRED PICKPOCKET

ОглавлениеJIMMIE ILES was ‘some dip’. That was how he would have put it himself. In the archives of the New York Central Detective Bureau the description was less concise, but even more plain: ‘James (Jimmie) Iles, alias Red Jimmie, alias, etc … expert pickpocket …’

And Red Jimmie, whose hair was flame coloured and whose indomitable smile flashed from ear to ear on the slightest provocation, would have been lacking in the vanity of the underworld if he had not been proud of his reputation at Mulberry Street. Nevertheless, fame has its disadvantages, and though he was on friendly terms with the headquarters staff individually, he hated the system that had of late prevented his applying his undoubted talents to full profit.

England beckoned him—England, where he could make a fresh start with the past all put behind him. Do not make a mistake: Jimmie had no intention of reform. But in England there were no records, and consequently the police would not be allowed points in the game. It would be hard, therefore, if an energetic, painstaking man could not pick up enough to keep him in bread and butter.

Behold Jimmie, therefore, a first-class passenger on the S.S. Fortunia—‘Mr James Strickland’ on the passenger list—a suit in the Renaissance style of architecture built about him, the skirts of his coat descending well towards his knees, his peg-top trousers roomy and with a cast-iron crease. Behold him explaining for the fiftieth time to one of his sometime ‘stalls’ the reason that had driven him from God’s own country.

‘I’m too good-natured. That’s what’s the matter with me. The bulls are right on to me. If I carried a gun or hit one of ’em, like Dutch Fred, I might get away with it sometimes. But I can’t do it. They’re good boys, though they’ve got into a kind of habit of pulling me whenever they’re feeling lonely. I can’t go anywhere without a fourt’ of July procession of sleuths taggin’ after me— Holy Moses, there’s one there now. How do you do, Mr Murray? Say, shall we find if there’s a saloon?’

Detective-Sergeant Murray grinned affably. ‘Not for mine, Jimmie old lad. I’ve got that kind of lonesome feeling. Won’t you see me home?’

Jimmie thrilled with a tremor of familiar apprehension. ‘Honest to Gawd, I ain’t done a thing,’ he declared earnestly. ‘You’re only jollying, Mr Murray?’

The officer laughed and vanished. Jimmie decided to make himself inconspicuous till the vessel sailed. Luckily for his peace of mind, he did not know that the Central Office was paying him the compliment of a special cable in order that he might receive proper attention when he landed.

Jimmie was ‘good’ on board, though more than once he was tempted. It was not till he was on the boat-train from Liverpool to London that he fell. There was only one fellow-passenger in the compartment with him—a burly, prosperous man of middle age whom Jimmie knew from ship-board gossip to be one Sweeney, partner in a Detroit firm of hardware merchants. There was a comfortable bulge in his right-hand breast pocket—a bulge that made Jimmie’s mouth water. He had no fear but that he could reduce that swelling when he chose. The only trouble was ‘the getaway’. He had no ‘stalls’ to whom to pass the booty. He would have to lift the pocket-book as they got out at Euston if he did it at all. It was too risky to chance it before.

Five minutes before the train drew in at Euston, Sweeney began to collect his hand baggage. He patted his breast pocket to make sure that the pocket-book was still there. Jimmie felt pleased that he had restrained himself. He brushed by Sweeney as the train drew up, and as he passed on to the platform he knew the exultation of the artist in a finished piece of work. The pocket-book was in his possession.

Not until he had reached his hotel, and was safe in the seclusion of his own room did he examine the prize—having first ordered a fire in view of eventualities. There was a bunch of greenbacks and English notes totalling up to forty pounds—not a bad haul. Also there were a score or so of letters. Jimmie dropped the pocket-book itself on the fire, and raked the coals round it. Then he settled himself to read the correspondence before consigning it to the flames. Waste not, want not; and although Jimmie held rigidly to the line of business in which he was so adept, he was not averse to profiting from the by-products. One never knew what information might be in a letter. Jimmie had more than once gained a hint which, passed on to the right quarters, had earned him a ‘rake off’ from a robbery that was decidedly acceptable.

There seemed, however, nothing of that kind here. The letters were merely ordinary business jargon on commonplaces of commerce, and half a dozen or so introductions which a business man visiting Europe might be expected to carry. One by one the flames consumed them. Then he came to the last one and hitched his shoulders as he read. It had been printed by pencil, evidently at some trouble.

‘DEAR SWEENEY,—We are not going to be played with any longer. If you are in earnest you will come over and see us. The Fortunia sails on the seventeenth. The evening following her arrival, one of us will wait for you between ten and twelve at the Albert Suspension Bridge, Battersea. You will make up your mind to come if you are wise. We can then settle matters.—O. J.’

A man may be a pickpocket and retain a certain amount of human nature. A crook who is in business for profit rarely has opportunities to consider romance. If there is anything in the nature of a show, he usually plays the part of the foiled villain. So if he has a taste that way he indulges in fiction, the theatre, or the cinema, so that he can safely gratify his natural sympathies on the side of virtue. Jimmie was fond of the cinema. Often he had been so engrossed by the hair-raising exploits of a detective that he had totally neglected the natural facilities afforded by darkness and entertainment.

Now, however, he was suddenly plunged into an affair that promised real life melodrama. The printed characters, the mysterious appointment late at night, the ambiguous threat, were something for his imagination to gloat over. His fertile brain wove fancies of the Black Hand, the Mafia, and kindred blackmailing societies which the Sunday editions of the New York papers had painted crimson in his mind. He thrust the letter into the fire, and went out in search of one Four-fingered Foster, sometime an associate of his in New York, now established in a snug little business ‘bunco steering’ in London. Foster had been notified in advance of his coming.

He found his four-fingered friend established under the rôle of an insurance agent at a Brixton boarding-house, and Foster was willing and anxious to show the friend of his youth the town. So thoroughly indeed did they celebrate the reunion that ten o’clock had gone before Jimmie recalled the note. He swallowed the remnants of some poisonous decoction while they lounged before the tall counter of an American bar near Leicester Square.

‘Say, Ted,’ he remarked, his pronunciation extremely painstaking. ‘Where’s Albert Bridge?’

‘Search me,’ answered his friend. ‘Who is he? What’s your notion?’

‘It’s a place,’ exclaimed Jimmie. ‘I gotta get there. Got a—hic—’pointment.’

‘We’ll go get a cab,’ said Foster, staggering away from the bar. ‘Taxi driver sure to know.’

Jimmie grabbed him by the lapel of his coat. By this time he had made up his mind that the Black Hand had got its clutches on the prosperous Sweeney, and he had a fancy that he might play the part of hero in the melodrama. Friendship was all very well, but it could be stretched too far.

‘’Scuse me, Ted.’ He rolled a little and steadied himself with one hand on the bar counter. ‘Most particular—private—hic—’pointment.’

‘Aw—if it’s a skirt—’ Foster was contemptuous.

Jimmie did not enlighten him. His wits never entirely deserted him. He moved uncertainly to the door, explained his need to the uniformed door-keeper, and soon was flying south-west in a neat green taxi.

The driver had to rouse him when he reached his destination. Jimmie paid him off and began to walk under the giant tentacles of the suspension bridge, his blue eyes roving restlessly about. It was very lonely. He passed a policeman, and then a stout man came sauntering aimlessly along. Sweeney did not seem to recognise Jimmie, and Jimmie did not wish to attract his attention yet. Apparently the Black Hand emissary—Jimmie was sure it was the Black Hand—had not yet turned up. Out of the corner of his eyes he saw Sweeney standing absently near the iron rail gazing down on the swirling, blackened waters beneath. The pickpocket passed on.

He had gone a dozen paces when a thud as of a heavy hammer falling upon wood brought him about with a jerk. He had recognised the unmistakable report of an automatic pistol. Into his line of sight came a vision of Sweeney, no longer on the pavement, but in the centre of the roadway. He was on his knees, and while Jimmie ran, he fell forward. There was no sign of an assailant.

Jimmie knelt and raised the fallen man till the body was supported by his knee. There was a thin trickle of blood from the temple—such a trickle as might be caused by a superficial surface cut. The American loosened the dead man’s collar.

It had all happened in a few seconds, and even while he was trying to discover if there was life remaining in the limp body, the constable he had passed came running up. ‘What’s wrong here?’ he demanded.

Jimmie, satisfied that the man was dead, laid the body back gently, and brushed the dust from his trouser-knees as he stood up. ‘This guy’s been shot,’ he said. ‘The sport that did it can’t have got far. He must have been hiding behind one of the bridge supports.’

The constable placed a whistle to his mouth in swift summons. Then he in turn knelt and examined the dead man. Jimmie stood by, his hands thrust deep in his pockets, his eyes searching every shadow where an assassin might still be in hiding.

The deserted bridge had suddenly become alive. In the magical fashion in which a crowd springs up in places seemingly isolated, scores of people were concentrating on the spot. Among them were dotted the blue uniforms of half a dozen policemen.

Jimmie had given up any idea of being a hero, but he still saw the tragedy with the glamour of melodrama. He watched with interest the effective way in which the police handled the emergency. A sergeant exchanged a few swift words with the original constable, and then took charge. The crowd was swept back for fifty yards on each side of the murdered man. Jimmie would fain have been swept with it, but a heavy hand compressed his arm and detained him.

The sergeant gave swift orders to a cyclist policeman. ‘Slip off to the station. We want the divisional surgeon and an ambulance. They’ll let the Criminal Investigation people know.’

A murder, whatever the circumstances, is invariably dealt with by the Criminal Investigation Department. The uniformed police may be first engaged, but the detective force is always called in.

‘Now, Sullivan, what do you know about this?’

The constable addressed straightened himself up. ‘I was patrolling the bridge about five minutes ago,’ he said. ‘I passed him’—he nodded to the dead man. ‘He was walking slowly to the south side. I didn’t pay much attention. A little farther on I passed this chap’—he indicated Jimmie—‘but I didn’t pay any particular attention. I had just reached the other end when I heard a shot. I ran back, and found the first man being supported by the other, who was searching him. There were no other persons on the bridge to my knowledge.’

Jimmie’s mouth opened wide. He was thunderstruck. ‘Searching him!’ he ejaculated. ‘Say, Cap’—he was not quite sure of the sergeant’s rank—‘I never saw the guy in my life before. I was taking a look around when I heard a shot. I was just loosening his clothes when this man comes up.’

He was too paralysed to put all he wanted to say into coherent shape. He was sober enough now. A man confronted with a deadly peril can compress a great deal of thinking into one or two seconds. Jimmie could see any number of points that told against him, and he strove vainly to concoct some plausible explanation. The entire truth he rejected as seeming too wild for credit.

‘Better keep anything you’re going to say for Mr Whipple,’ advised the sergeant. ‘Two of you had better take him to the station.’

With his head buried in his hands, Jimmie sat disconsolate on a police cell bed. He was filled with apprehension, and the more he considered things, the more gloomy the outlook appeared. For an hour or more he waited, and at last he heard footsteps in the corridor. A face peered through the ‘Judas hole’ in the cell door, and then the lock clicked.

‘Come on!’ ordered a uniformed inspector. ‘Mr Whipple wants to see you.’

‘Who’s Mr Whipple?’ demanded Jimmie drearily.

‘Divisional detective-inspector. Come, hurry up!’

There were places in the United States where Jimmie had been through the ‘sweat-box’ and though he had heard that methods of that kind were barred in England, he felt a trifle nervous. He preceded the inspector along the cell-lined corridor, through the charge-room, and up a flight of stairs to a well-lighted little office. Two or three broad-shouldered men in mufti were standing about. A youth seated at a table with some blank sheets of paper in front of him was sharpening a pencil. A slim, pleasant-faced man was standing near the fireplace with a bowler hat on his head and dangling a pair of gloves aimlessly to and fro. It was his eyes that Jimmie met. He knew without the necessity of words that the man was Whipple. He pulled himself together for the ordeal of bullying that he half expected.

‘I don’t know nothin’ about it, chief,’ he opened abruptly and with some anxiety. ‘I’m a stranger here, and I never saw the guy before.’

‘Take it easy, my lad,’ said Whipple quietly. ‘Nobody has said you killed him yet. I want to ask you one or two questions. You needn’t answer unless you like, you know. If you can convince us that you were there only by accident, and had no hand in the murder, so much the better. But remember you’re not forced to answer. Everything you say will be written down. Give him a drink, somebody. Now take it quietly, old chap. What’s your name?’

His voice was soothing, almost sympathetic. It gave Jimmie the impression, as it was, intended to, that here was a man who would be scrupulously fair. He drank the brandy which someone passed to him, and for an instant his old, wide-mouthed smile flashed out. The spirit gave him a momentary touch of confidence.

‘That’s all right, boss. James Strickland’s my name. I’m from New York. Come over in the Fortunia and landed this morning.’

‘What are you?’

‘Piano tuner.’ The trade was the first one that occurred to Jimmie. ‘Over here to see if there’s an opening,’ he rattled glibly. ‘Trade’s slack the other side.’ The shorthand writer’s pencil scratched rapidly over the paper. Whipple’s face was expressionless.

Question succeeded question, each one quietly put, each answer received without comment. Jimmie was becoming involved in an inextricable tangle of lies. Had not the horrible fear still loomed over him, he might have avoided contradictions, extraordinary improbabilities, and constructed a connected, if false, story. And he could see, not in his interlocutor’s face, but in the faces of the others, a scepticism which they scarcely troubled to conceal.

The catechism finished, Whipple began drawing on his gloves.

‘That will do. You will be detained till we have made some more inquiries.’

Jimmie shuddered. ‘You don’t really think I done this, boss? You aren’t goin’—’

‘You’re not charged yet,’ said Whipple. ‘You’re only detained till we know more about things.’

It was a poor consolation, but with it Jimmie had to be content. He was taken below, and Whipple turned an inquiring face on one of his sergeants. The man made a significant grimace. ‘Guilty as blazes, sir,’ he said emphatically. ‘What did he want to tell that string of lies for?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Whipple thoughtfully. ‘You’d be thrown a little off your balance, Newton, if you were suddenly up against it. He’s a liar, but he’s not necessarily a murderer.’

Newton grunted, but ventured no open dissent till his superior had gone. He was a shrewd man in dealing with the commonplaces of crime, but he lacked subtlety, and accordingly despised it. ‘The guvnor’s too kid-glove,’ he complained with asperity to the uniformed inspector. ‘What’s the use of mucking about? The bloke’s a Yankee crook. He admits he came over in the Fortunia, and says he don’t know Sweeney, who came over in the same boat. Why, he must have been laying for him. He must have shadowed him till he got a fair chance. Mark me, when we’ve traced those notes we took off Strickland, we shall find that they were originally paid out to Sweeney. Waste of time finicking about, I call it.’

Now some of this reasoning had been in Whipple’s mind, but he liked to feel the ground secure under his feet before he took an irrevocable step. There was no hurry—at any rate for the twenty-four hours during which he was entitled to detain Jimmie on suspicion without making a charge. But there were certain points on which he was not entirely satisfied.

He was on hand at Scotland Yard early next morning. The report of the tragedy was in the morning papers, but they had given it little prominence. From their point of view it was of little news value—just a shooting affray, with a man detained. This was the view the superintendent of the Criminal Investigation Department, to whom Whipple had come to report, took of it.

‘Straightforward case, isn’t it, Whipple?’

‘There are one or two queer points about it, sir. I must admit it looks rather bad for Strickland, but somehow I don’t believe he did it. I can’t say why, but that’s my impression.’

‘You must be careful of impressions, Whipple. They carry you away from the facts sometimes.’

‘I know that. Well, the facts are these: Sweeney, the dead man, was the president of a hardware company at Detroit. I sent a cable off last night. He had come over partly on business, partly on pleasure, and was held in very good repute there. About five minutes ago I got this fresh cable.’ He smoothed out a yellow strip with his hand and read: ‘“News Sweeney’s death precipitated crash his firm. His business unsound for years. Insurance company informs us recently increased life premiums for half-million dollars. Suspect fraud. Request you will make stringent tests of identity, alternatively suspect suicide.” That’s signed by the Detroit Chief of Police.’

The superintendent stretched out a hand and took the cablegram. He read it through twice with puckered brows. ‘That’s a queer development,’ he admitted. ‘I don’t see what they’re getting at. If the murdered man is not Sweeney, that hypothesis assumes that Sweeney got someone else to impersonate him and that the second person knew he was to be killed. That’s ridiculous.’

‘So I think, sir. There’s more to the suicide end. The divisional surgeon says that the dead man’s temple was blackened by the explosion of the pistol. That shows that the weapon, when it was fired, was but a few inches from his face. Of course, when I saw the surgeon I didn’t know what this cable tells us, but luckily I put the point to him. There was no weapon found. I asked him if, supposing that Sweeney had killed himself, he could have thrown the pistol into the water after pulling the trigger—it was a distance of several yards to the parapet of the bridge. He was emphatic that it was impossible.’

‘Then it comes back to murder after all. Yes. it’s certainly curious about the insurance. Who’s the chap you’ve got in?’

Jimmie would have been interested in the reply even had he been less vitally concerned. It would have shown him how vain were his hopes of cutting away from his record. ‘A little red-haired chap with a big mouth, who gave the name Strickland—a Yankee pickpocket, Jimmie Iles, or Red Jimmie. You’ll remember, sir, New York cabled us he had sailed.’

‘Yes, I remember. We ought to have something about him then.’

‘We have. I spent part of last night picking it up. The Liverpool men spotted him in a compartment of the boat-train, alone with a man who fills the description of Sweeney. Sergeant Fuller, who was on duty at Euston, saw him when he arrived and took the number of his cab. He was not with Sweeney then. We found the cabman early this morning. He had driven him to a little hotel off the Strand. The hotel people remember him because he wanted a fire in his bedroom—a fire this weather! He went up there and stayed for over an hour. Then he went straight out.

‘At nine o’clock Tamplin of the West End saw Four-fingered Foster in the Dewville Bar, Coventry Street, with a red-haired American whom he thought was being strung. The Grape Street people recalled this when the tape report of the murder came over to them. I sent a man to rake out Foster, and sure enough his red-haired pal was Jimmie. Foster said they had parted in the Strand about eleven o’clock. Jimmie said he had an appointment at the Albert Bridge—Foster thought with a girl …

‘Those are pretty well all the facts, except this: when Jimmie was searched at the police station there were found on him three five-pound notes. These notes had been issued to Sweeney by a bank at Detroit before he left. I have the man’s own statement here, sir, if you’d care to look at it. It’s a string of lies.’

His chief waved aside the document and fiddled with his pince-nez as he considered the problem for a while. ‘You’re right to go easy, Whipple, but don’t overdo it. There’s almost enough evidence as it is to hang Red Jimmie. Intuition is good, but a jury won’t be interested in your psychology. They’d sooner read a book.’

‘Very good, sir.’ The detective-inspector went away, still far from satisfied. In view of the evidence now accumulated, he would have been inclined to believe Jimmie guilty had it not been for the singular news of Sweeney’s smash and the insurance. Coincidence is a factor in criminal investigation work, but this was straining it. If Sweeney had been murdered, the crime had come just right to provide for his family.

‘There’s some point that I’ve overlooked,’ he murmured to himself. ‘I can’t quite place it.’

He went back over the Albert Bridge to the police station, but no inspiration came to him. There was a bundle of reports awaiting him in his office, but after a casual glance he flung them aside and went down to the cells. He wanted to see Jimmie alone.

Jimmie looked up with pitifully haggard face as the door clanged behind the detective. Whipple nodded cheerfully and sat down.

‘Jimmie,’ he said familiarly, ‘wouldn’t you like to give me the straight griffin? I’ve heard from New York. You’d better let me know exactly what happened. What passed between you and Sweeney in the train coming down from Liverpool?’

He spoke in a quiet, conversational tone, but Jimmie jerked his head back as though to avoid a blow. He had had plenty of time to reflect on the leading points of circumstantial evidence that told against him. It staggered him more than a little that the police had been so quickly able to follow his trail backwards. He was conscious of his innocence of the major crime, conscious also that there was nothing he could do or say which would get away from the deadly array of facts that pointed against him.

‘Well, Jimmie?’ said Whipple persuasively.

Jimmie ran a hand through his dishevelled red hair. Then he shook himself as though trying to throw off the thoughts that possessed him. ‘See here, boss,’ he cried in an impulsive burst, ‘I’ll put you wise to the whole shemozzle. You won’t believe me anyway, but it’s the solemn truth, so help me. The bulls, they wouldn’t give me a rest in New York, so I chased myself over here where I’ve got one or two chums.’

‘Four-fingered Foster?’ queried Whipple absently. His thoughts were quite away from Jimmie, but he was nevertheless keenly following every word.

‘Has he squealed? Never mind, it don’t matter. Well, on the boat I got some chances, but I held myself in. There’d been a Central Office man to see me off, and I didn’t know but what he might have passed the word. I cut out the funny business till I got ashore, but I marked out one or two likely guys, Sweeney amongst them. Of course I steered clear of them on the ship, didn’t talk to ’em or nothing. I didn’t want to be noticed too much—you understand? When we shifted over into the boat-train at Liverpool, I saw Sweeney on his lonesome and got into the carriage with him. I lifted his leather from him—I admit that, boss—just as we reached London.’

‘You picked his pocket?’

‘Yes, his pocket-book. Then I went on to my hotel and sorted out the stuff. Some of them notes they took off me when they brought me in was among them. Then there was a lot of letters.’

‘What did you do with them?’

A flash of cunning crossed Jimmie’s face. ‘What do you think? Burnt ’em. Things like that don’t talk when they’re in the fire. There was one there, though, that I wish I’d saved now. It was written in print, if you understand what I mean, and told Sweeney to meet someone who had wrote it at Albert Bridge.’

‘Wait a minute. Can’t you remember exactly what it said?’

Jimmie wrinkled his brow in cogitation. Slowly he repeated the letter, which Whipple took down in shorthand on the back of an envelope. ‘I thought,’ said Jimmie, a little haltingly, ‘that I might butt in and catch this Black Hand gang and do Sweeney a turn. You see, I never believed in this gun-play myself, and I thought if I could stop it I might put myself right with Sweeney and perhaps he’d put me on to something—’

‘Take you into partnership,’ said Whipple; ‘saviour of his life and all that kind of thing.’

‘That’s it,’ agreed Jimmie.

Whipple smiled inwardly, but his face was grave. ‘And you want me to believe this yarn that you’ve been sitting thinking out, do you? Ah—don’t be a fool.’

Jimmie was utterly unstrung, or he never would have allowed himself a resort to violence which, even if it were successful, must have been futile. He thought he saw that he was still disbelieved, and had leapt at the detective’s throat with a mad idea of escape. Whipple side-stepped quickly, stooped, and the pickpocket felt himself lifted and flung to the other side of the cell.

‘Don’t be a fool, Jimmie,’ repeated Whipple mildly. ‘Even if you did knock me out, you couldn’t do anything. The cell is locked on the outside, and even I can’t get away till I ring. Sit down again quietly—that’s right. Now tell me one other thing: Did you notice anything in particular when you got on to the bridge last night?’

The other rubbed himself tenderly. ‘Nothing in particular,’ he answered. ‘There was a smell of paint—that’s not much good.’

‘Isn’t it!’ said Whipple, and pressed the bell that summoned the gaoler.

Two men sauntered on to the Albert Bridge. Whipple had got an idea, and though he had yet to test it, he was convinced that he was on the right track at last. He nodded as he saw the fresh green paint on the rails, and kept his eye fixed on them till he had passed a dozen yards by the spot where the murder had been committed. Then the two crossed to the other side of the bridge. The inspection of not more than three yards of the rail had taken place when Whipple halted and gave a satisfied chuckle. ‘We’re on it, Newton,’ he declared. ‘Look here.’

He pointed to some marks on the fresh paint-work. Across the top of the upper part of the rail, and continued downwards on the outer side, the paint had been scraped away. On the river side there were a couple of irregular bruises on the paint.

‘Kids been playing about,’ said the sergeant with decision. ‘I remember in the flat murder case we got mucked about by a lot of marks on a doorway. Some bright soul thought they were Arabic characters. It turned out they were boy scout marks.’

The detective-inspector laughed. ‘All right. Seeing’s believing with you. I’ll have a shot at this my own way, though. You might go and phone through to the river division. Ask ’em to send a couple of boats up here with drags.’

Newton spat over the rail into the tide. ‘You’ll not find anything with drags,’ he said, and with this Parthian shot, went to obey his instructions. Whipple remained in thought. Once, when there was a lull in the traffic, he paced out the distance between the marks on the rail and the place where Sweeney had been killed.

‘I’m right,’ he declared to himself; ‘I’d bet on it.’

Within twenty minutes two motor-launches were off the bridge and Newton had returned. Leaving him to mark the spot where the paint had been rubbed on the rail, Whipple went down to be picked up off a convenient wharf. A short discussion with the officer in charge as to the effect of the tide-drift, and they were in mid-stream again.

Then the drags splashed overboard and they began methodically to search the bed of the river. When half an hour had gone, Whipple was beginning to bite his lip. A drag came to the surface with whipcord about its lines. A constable began to unwind it. The detective leaned forward eagerly. ‘Steady, man, don’t let it break, whatever you do.’

They pulled the thing attached to the string on board and steered for the bank, Whipple in the glow of satisfaction that comes to every man who sees the end of his work in sight. He went straight to the police station telegraph room.

‘Whipple to Superintendent C.I.,’ he dictated. ‘Inform Detroit police Sweeney’s insurance void. Absolute proof committed suicide. Details to follow.’

Later, in his own office, his stenographer took down to be typed for record:

‘SIR,—I respectfully submit the following facts in regard to the supposed murder of the man Sweeney—

‘I first gained the impression that it was suicide from the doctor’s report that the explosion of a pistol had scorched the dead man’s face, showing that it had been held very closely to his head. This impression was strengthened by the fact that Iles, the American who was found by the body and at first suspected of the murder, could, if his motive was robbery, have attained this end more simply without violence. He is known to the New York police as an expert pickpocket. I need scarcely add that the knowledge that Sweeney was practically a bankrupt before he left the United States and had insured himself very heavily disposed me still more to the theory of suicide. If Sweeney had it in his mind to kill himself, it was indispensable to his purpose (since practically all life insurances are void in the event of suicide) to make the act appear (1) as an accident; (2) as a murder. He chose the latter.

‘Unfortunately for himself, Iles picked Sweeney’s pocket on the journey to London. Whether the latter discovered his loss before his death it is impossible to say with certainty. I believe not. Among the documents which Iles found was a letter in printed characters (which with others he burnt) demanding an appointment on the Albert Bridge, and conveying indirect threats. It is my belief that this letter was written by Sweeney himself with the idea that it would be found on his body and confirm the appearance of murder. I considered very fully the various means by which Sweeney might dispose of a pistol after he had shot himself. Only one practicable way occurred to me, and this was confirmed by an examination of the bridge rail, which had been newly painted. There were the paint stains on the dead man’s clothes, and Iles had said he noticed him looking over the rails.

‘It seemed to me that if the butt of a pistol were secured to a cord, and a heavy weight attached to the other end of the cord and dropped over the rail of the bridge before the fatal shot was fired, the grip on the pistol would relax and it would be automatically dragged into the water. The river was dragged at my request, and the discovery of an automatic pistol tied by a length of whipcord to a heavy leaden weight proved my theory right … With regard to Iles, I shall charge him with pocket-picking on his own confession, and ask that he shall be recommended for deportation as an undesirable alien … I have the honour to be your humble servant,

‘LIONEL WHIPPLE,

‘Divisional Detective-Inspector.’

‘All the same, sir,’ commented Detective-Sergeant Newton, ‘it looked like being that tough. He’s in luck that you tumbled to the gag.’

‘That’s right,’ agreed Whipple smilingly. ‘It’s luck—just luck.’