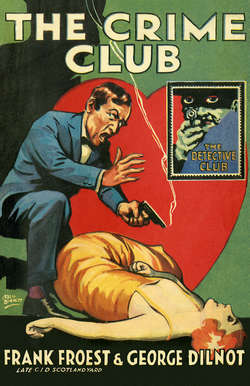

Читать книгу The Crime Club - Frank Froest, David Brawn, Frank Richardson - Страница 9

IV THE MAKER OF DIAMONDS

ОглавлениеFLEETING twisted his watch-chain absently around his fingers till it cut the flesh.

‘They’re diamonds all right, all right,’ he said. ‘That’s the blazes of it.’

Heldway smiled genially at the jeweller. ‘Where do I come in then? I don’t see what you’ve to complain about. You admit, yourself, there’s a fortune in it.’

He spoke quietly, yet there was a subtle inflection of irony in his tone that caused the jeweller to scrutinise his face with suspicion. Somehow Heldway made him feel a fool, and Fleeting knew he was not a fool. He recognised himself—more, other men recognised him—as one of the keenest jewellers in Hatton Garden.

Being a jeweller, he was one of the least credulous of men. It spoke for itself that he had called in Heldway. There were those at Scotland Yard who held Heldway in high esteem.

‘There’s a screw loose somewhere,’ he protested, releasing his chain and pushing out a pair of delicate hands. ‘I feel it. The thing’s too good to be true. Why, if I hadn’t seen it myself, I’d have sworn those diamonds came from Kimberley.’

The detective-inspector shrugged his shoulders listlessly. ‘Ah, of course, an expert can always tell which mine a stone has come from.’

Fleeting seethed inwardly. He was in a burning excitement, and the placidity of the other annoyed him. He did not consider that while his own agitation was to be attributed to the possibility of making a fortune beyond his wildest dreams, or losing a sum that would long cripple him, the detective had nothing to gain or lose.

‘What do you make of it?’ Fleeting demanded bluntly.

Heldway slowly changed his position till his elbow rested on the mantelpiece. He seemed to be weighing the question. At last he spoke. ‘What it comes to is this: This man Vernet says he can make diamonds, and offers to sell a half-interest in his secret to you for a hundred thousand pounds. He gives a demonstration under the most stringent tests, and you fail to find out any fake. The diamonds are genuine. Now it seems to me one of two things—either Vernet can do what he says, or your precautions against trickery have not been effective.’

‘Hang it all!’ retorted Fleeting impatiently. ‘What more could I do? The room in which he works is here in my office. It was fitted up by firms whom I specified, according to his ideas, with a little charcoal furnace and certain chemical preparations. I did all the buying. Everything passed through my hands. It is impossible that he should have had any confederate among the workmen. When he has gone in to supervise the construction of the furnace, I have been with him, watching every movement. That he could have hid anything in the room is quite impossible.’

‘Have you seen him actually make these gems?’

‘No,’ admitted Fleeting. ‘I can’t very well expect him to lay his hand down till I have paid cash. It’s too big a thing to take chances on. Mind you, Vernet’s perfectly reasonable. He invited me to take precautions against trickery, and I have. Each time he goes into the laboratory he changes every stitch of clothing for a suit I have provided. I have engaged an expert searcher, who used to be at the diamond fields, to examine his hair, his mouth, his ears, and so on. I have stood guard over the door while he’s been inside. And always he has come out with perhaps one, perhaps two, perhaps three, rough stones, well up to the average size and quality.’

Heldway had been softly whistling a bar of ragtime. He broke off to press home the logical fact. ‘Well, if they’re not already in the room, and he doesn’t take ’em in, he must manufacture them.’

‘I wish I could be sure,’ said Fleeting. ‘It seems all right, and yet—one does not like to sink a hatful of money … I want to be dead sure. That’s why I’d like you to look into the business.’

The detective-inspector settled himself in a chair. ‘The long and short of it is, that you’re in for a gamble and want to be sure you’ll win before you risk your money. I guess you know if I take it up, and it is a swindle, you’ll have to take it into court. Let’s be clear about that.’

The jeweller reddened. ‘Look here, Mr Heldway, I don’t mind so much myself; but there’s another thing—my daughter—’

‘Oh, there’s a lady in the case?’ The corners of Heldway’s eyes wrinkled. ‘Suppose you tell me all you know about Vernet.’

‘We ran across him while we were in Chamonix last summer,’ replied Fleeting. ‘You know how one falls into these holiday acquaintanceships. Don’t run away with the idea that I’ve got any fixed suspicions of him, Mr Heldway. I believe in him—but I want to be sure. He’s certainly a gentleman, and he was in touch with some very nice people. He made himself agreeable to Elsie—that’s my daughter—and he and I fell rather together. I’m not impressionable, but I must say I like him. Apart from the money, I should be sorry if there were any fake in this. I should put him about thirty. His mother was English and his father French. He’s got a little estate in France, but for these last ten years has been knocking about the world. He speaks English as well as you or I …

‘Of course my business leaked out. I’m a pretty well-known man. I don’t remember precisely how the matter arose, but one day Vernet asked me for a private interview. I thought he wished to see me about something else—’

‘Miss Fleeting?’ interjected Heldway.

‘Yes …’ Fleeting hesitated. ‘I didn’t intend to tell you this, Mr Heldway, but you may as well know it. It makes the situation rather more delicate. He did see me about Elsie, but he introduced the other affair, and that matter remains in abeyance for the time being. He told me he had stumbled on the discovery while making certain chemical experiments, and offered to submit to any test I might propose short of showing me the actual process. I, of course, accepted, and invited him over to my little country-place till inquiries were completed.’

The detective’s whistling stopped. ‘Made any inquiries about the chap?’ he demanded.

‘Naturally. His estate is near Danville in the Department of Eure. I pleaded business in London, and put a couple of days in there myself as a tourist. I corroborated all that he told me about his affairs. His income, translated into English, would be about seven hundred a year. Nothing tremendous, but quite enough.’

A superficial insight might hold that a lifetime of detective work would make a man a cynic. Heldway had his share of cynicism, but, like all successful men of his profession, he had sympathy. He could appreciate something of the diverse feelings by which the jeweller was torn—his care for his daughter, his pocket, his vanity. He rose and dropped his hand lightly on the other’s shoulder.

‘When does the next demonstration take place?’

‘On Monday.’

‘Good. Now, can you invite me down to your place for the weekend as a friend? I’d like to see Vernet. Meanwhile, if you’ve got a photograph of him, any writing, any scrap of material concerning him, you let me have it. And by the way, I’d like a description of Vernet—hair, eyes, height, and so on. Good-bye for the present. I’ll be down some time Saturday afternoon.’

Ten minutes later Heldway sauntered out of the office, whistling softly. He did not wonder that Fleeting, canny man, felt uneasy. The making of diamonds—profitably—was a big thing, and a man who could prove his good faith would easily obtain more than one hundred thousand pounds for a half-share. True, there was Elsie Fleeting—but, not having seen her, Heldway did not know exactly how far she might weigh in the transaction.

The spade work of detection is a laborious business, but very necessary to every detective outside the story-books. Juries do not convict on theories, however brilliant and plausible. They want facts—facts that can be sworn to. And so far Heldway had no facts—only a statement by Fleeting.

For half an hour or more Heldway laboured diligently. The Criminal Record Office put him in possession of facts relating to every one of the adventurers of this type known to be in England. Big Grant, the head of the department, who knew the science and practice of identification backwards, assisted in a close comparison of the portraits available with the amateur photograph of Vernet in the midst of a group which Fleeting had supplied. But they drew blank.

The finger-prints of Vernet might have simplified the search to a matter of minutes. As they were not available, the Record Office staff was set to work to trace through the old system of indexes, a tedious, lengthy job, by the light of the description Vernet had offered. They looked not under the letter ‘V’, but in that section of the records devoted to men of five feet nine in height with brown hair and hazel eyes.

This phase of the search Heldway left to the department, though at times he brought in a colleague to examine the photograph on the chance that Vernet might be recognised. At intervals he despatched cryptic cables to Paris and New York. Possibly Roger Vernet would have been flattered had he known how many people were being stirred to an interest in his career.

A neat little motor-car was waiting for Heldway at Haslemere station, and a run of a couple of miles brought him to a pine-shaded villa in which Fleeting had his country retreat. The detective nodded approval at the trim gables, the rose-bordered lawn, and the well-rolled gravel paths.

Fleeting, a little nervous and ill at ease, welcomed him with effusion, and with a wave of his hand introduced the couple who were standing in the shade of the veranda.

‘Mr Heldway—my daughter. Vernet, a friend of mine—Mr Heldway.’

The detective found himself gripping a slender, almost effeminate hand, and Vernet’s eyes did not drop under his scrutiny. Indeed, they were scrutinising him with a languorous ease that was almost insolent. The maker of diamonds had no appearance of the scientific student. He had been dressed by an artist in tailoring. His boots, his meticulously creased trousers, the sloping waist of his jacket, were all beyond criticism. He had a little toothbrush moustache, which he stroked from time to time with a delicate forefinger. His handkerchief was tinged with scent. Heldway, who was not self-conscious, felt uncouth in his presence.

‘Delighted to know you,’ said the young man, but his face had the abstract look of one wrestling with an abstruse mental problem. Heldway wondered if he had any suspicion of his identity. He murmured some commonplace, and his gaze wandered momentarily to the girl—a picture in grey and white. Erect and slender, with sparkling blue eyes and cheeks tanned to a wholesome clearness by fresh air and exercise, she did not conform at all to his mental impression of her. This was not the sort of woman to become infatuated with an adventurer. And yet—

They went in to lunch. Heldway was a good talker when he was in the vein, and conversation moved swiftly. He set himself to draw Vernet out, and the other was nothing loath. He had apparently been everywhere and seen everything.

‘If this man’s playing with a cold deck, he’s got a nerve,’ meditated the detective.

Once, during a lull in the conversation, he again surprised the bland hazel eyes surveying him with abstract calculation. Vernet pulled himself together.

‘Come, Mr Heldway, a man of your profession is always running against experiences. I appeal to Miss Fleeting. Here’s a real live detective, and he hasn’t told us one of his adventures.’

The shot was sudden, and for the moment Heldway was thrown off his balance. A flicker of astonishment passed across his features. Then he smiled. Vernet was evidently determined to drag him boldly into the open.

‘Are you a detective?’ inquired the girl. ‘How exciting! Dad only told us you were a friend of his.’

Heldway went imperturbably on with his sweet. ‘Yes, I am a detective, Miss Fleeting. I’m afraid it is not so exciting as the novelists would have you believe. How did you know?’ He addressed Vernet.

The other shrugged his shoulders. ‘I didn’t recall your face till this moment,’ he answered indifferently. ‘I saw you give evidence at the Old Bailey in a murder case last year. Are you down here on business?’

It was difficult for Heldway to repress a laugh. Whether Vernet was a rogue or not, he was not so simple as not to put a construction on the circumstances. ‘An official of police is always more or less on business,’ he parried. ‘But I’m here, through Mr Fleeting’s kindness, only for fresh air.’

‘So you haven’t brought your handcuffs?’ Vernet was smiling inwardly. The official wondered if he meant a challenge.

‘I don’t anticipate any occasion to use them down here,’ he laughed.

Fleeting, who had been fidgeting uneasily in his chair, broke in: ‘Here’s coffee. Have a cigar, Heldway. My daughter doesn’t mind. I never ask Vernet. He’s got his own particular brand of poisonous cigarettes. I believe he smokes them in his sleep.’

‘It’s a bad habit,’ said Vernet. ‘If I had any strength of will I should give them up. But I’m lost without a cigarette.’ He extracted a fat one from a gold case, and lighting it, blew a circle of smoke into the air. ‘If I were a criminal, now, there would be a clue for you, Mr Heldway. You’d only have to look for an insatiable consumer of cigarettes, like Raffles, eh?’

He held the white tube up to the light. ‘I have them specially made, with my initials on the paper.’

‘The perfect criminal—and thank Heaven there is none—would have no fixed habits,’ commented Heldway.

It was late in the evening before he got the chance of a word alone with his host. Miss Fleeting had accepted the diamond-maker’s challenge to billiards, and the two elder men were contemplating the moonlight from the veranda. Fleeting was anxious to make it clear that he had given no hint of the detective’s identity. Heldway brushed away his explanation.

‘Never mind about that. You haven’t shown me over the house yet. Suppose we take the opportunity now.’

‘I didn’t suppose you’d be interested. It’s entirely modern. However, come along.’

So it was that, when he retired, the detective had in his mind a very complete plan of the sleeping apartments of the house, especially the relation of his own bedroom to that occupied by Vernet. Beyond taking off his boots and collar, he had made no attempt to undress, He stretched himself out in an arm-chair with a novel, and composed himself to read until such a time as the household should be asleep. At two o’clock he laid aside his book and rummaged in his kit bag. A small electric torch about the size of an ordinary match-box, a dozen master-keys, and a red silk handkerchief with a couple of holes cut in it rewarded his search. The handkerchief he adjusted on his face, the holes serving as eye-slits. The keys and the torch he carried in his hands.

There are moments when a police officer steps out of the limits of strict legality. He knows how great a risk he runs, for if he fails of his purpose he can expect no countenance from his superiors. There was no possible excuse for Heldway in what was, in effect, an act of burglary. He had deliberately refrained from saying anything to Fleeting of his intention, partly, it must be admitted, because he was afraid that the jeweller might exercise a veto.

Softly he stepped into the corridor, his stockinged feet making no sound on the soft carpet. A thin thread of light cut through the darkness, affording just enough light to prevent his blundering into any furniture. More than once he switched off the light and stood stock still as his ear caught those indefinite sounds that are always audible in a sleeping household.

He reached Vernet’s door and softly turned the handle. As he expected, it was locked.

Very stealthily he tried his keys one after the other.

His muscles contracted involuntarily as a slight click told that the bolt had shot back. He stood stiffly, listening intently.

Five minutes elapsed before he ventured to thrust open the door and cautiously edge his way inside. He waited for a matter of seconds till the deep regular breathing from the bed reassured him. Then he flashed the bead of light on the wardrobe, and all his movements quickened. Whatever he sought he had guessed the diamond-maker would carry on him during the day—otherwise Heldway would not have waited till now to ransack the room.

Presently he gave an almost unconscious ejaculation of triumph, as he dragged out of a pocket a little wash-leather bag. With hasty fingers he opened it and directed the rays of his lamp on twenty or thirty uncut diamonds. And then, even while he chuckled to himself, the room was suddenly flooded with light. He wheeled abruptly. Vernet was sitting up in bed, one hand on the electric light switch, the other holding a revolver, its muzzle steadily directed towards Heldway.

‘Stand still, my friend.’ Vernet’s voice was cold and menacing. ‘Perhaps it would be as well if you put your hands above your head.’ His own hand had deserted the switch and began groping for the bell. ‘I see you have masked your face—a wise precaution.’

Heldway lowered his head, swerved sideways, and plunged forward so swiftly that it seemed as if all his movements were simultaneous. A quick report rang out, and a bullet shattered the glass of the wardrobe. Before Vernet’s finger could compress on the trigger again, Heldway was upon him. His full weight was behind his left as he swung it to Vernet’s jaw, and the man dropped limply back on his pillow.

The detective fled. It was a matter of seconds from the time Vernet had fired till he reached his own room and closed and locked the door. He could hear people rushing about and sleepy voices raised in inquiry. Hastily he tore off his clothes and tumbled into his pyjamas. A thunderous knock interrupted him before he had finished. He continued an audible yawn the while he ruffled his bed noiselessly to give it the appearance of having been slept in, and in his voice as he put a question was the querulous tone of a man just aroused.

‘It’s me—Fleeting. Wake up. There’s been burglars. They’ve murdered Vernet.’

‘Good heavens!’ There was a fervour that was unfeigned in the detective’s voice. He had had no time to calculate his blow with nicety, and trusted that he had not struck harder than he meant. A moment later he flung open the door, and while Fleeting waited, put on his slippers and dressing-gown. His alibi was convincing.

They went together to the diamond-maker’s room. He was relieved to find that Vernet was very far from dead, though still unconscious. ‘Somebody has knocked him out, that’s all,’ he diagnosed. ‘He’ll be all right in a little while.’ He turned on the group of servants who had gathered in the room. ‘Some of you men get out into the grounds. The burglar can’t have got far.’

‘Hadn’t someone better go for the police?’ said the jeweller.

‘Not worth while. They can do nothing tonight that we can’t do without them. If we don’t catch the man ourselves, I’ll run out to put the case in their hands myself.’

No one disputed his authority. He calculated that the flustered men-servants would make enough confusion in the garden to keep up the illusion of a burglar, and he did not want to have to cause the local police useless trouble. Nevertheless, after seeing Vernet comfortably disposed, he went to direct the search. He it was, curiously enough, who discovered a broken pane of glass in an unfastened scullery window—proof of the means by which the burglar had effected an entrance.

Nothing resulted from a search of the grounds. One man at least had scarcely expected there would. He was undecided whether to take Fleeting into his confidence. If all had gone well he would have done so—indeed, it would have been necessary to his plan.

‘I reckon that if Vernet was on the ramp he would have a stock of diamonds to draw on,’ he explained to a colleague later. ‘I wanted to lay my hands on them, and to get Fielding to weigh and measure and examine them, so that he could tell them again. Then I was going to replace them. If Vernet played any of them during his manufacturing stunt, then we would have had him.’

Heldway was a man who rarely did a thing without an object, and there was now no object in telling Fleeting. He might safely be allowed to nurse the delusion of a burglar if he would. The diamonds he resolved to keep, for the time being. Unless Vernet had a reserve store, which was unlikely, he would be forced to procure more or postpone Monday’s demonstration. There was, of course, the possibility that he really could make diamonds. But the detective had little fear of that.

‘Nothing gone,’ repeated Fleeting, who had been stocktaking with the butler. ‘That is, unless Vernet’s lost anything.’

‘Let’s hope he hasn’t,’ said Heldway cheerfully. ‘The chap’s got away, whoever he was. Perhaps Vernet will give us something to work on when he comes around.’

As a fact, Vernet a quarter of an hour later was able to throw little light on the situation. He was still a little dazed and unable to think or express himself clearly. ‘Woke up … masked man … going through my clothes … came for me … fired … missed him. Then he hit me.’ He lay back wearily and, at Heldway’s suggestion, was permitted to sleep.

But it was a different man who appeared at breakfast. Spruce and debonair, he seemed little affected by his adventure, as in well-chosen phrases he told of his encounter with the burglar. ‘He was confoundedly quick,’ he admitted. ‘I didn’t think I could have missed at that distance. As it was, all he got was a bag of twenty-five rough diamonds—the result of some of my experiments.’ He smiled brightly at Heldway.

‘Experiments?’ repeated the detective blankly.

‘Ah! I forgot, It’s a little secret between Fleeting and myself. By the way, Fleeting, can the chauffeur run me into Haslemere after breakfast? I want to send a wire.’

‘I’ll go with you if you don’t mind,’ interposed Heldway. ‘We may as well see the local police. This burglary is really their affair.’ He had his own ideas as to what Vernet’s wire might contain.

No one who beheld the two side by side in the car would have considered them as the hunter and the hunted, the attacker and the defender. Heldway had risen to Vernet’s flow of spirits, and accepted the light chaff of the other without resentment.

‘Now, if I didn’t know you were above suspicion,’ remarked the diamond-maker once, ‘I should be inclined to think you were the burglar all the fuss was about last night. He was just about your build.’

It was deftly conveyed intimation that Vernet had guessed something of the object of the midnight raid. Heldway laughed. ‘Oh, there’s no need for me to turn burglar yet.’

‘One never knows,’ retorted Vernet.

Vernet went on to the post office, but Heldway got out of the car at the police station. As a matter of detail he reported the burglary, and the facts were solemnly written down on an official form by the officer in charge. Looking up for a fresh dip of ink, the officer saw a wink flicker on Heldway’s grim face.

‘I shouldn’t waste too much trouble over the case if I were you,’ said Heldway. ‘Of course, it’s none of my business, but if I might suggest a policy of masterly inactivity—you understand?’

The other was a man of quick perception. He grinned. ‘Not altogether. I’m not going to cross-examine you. If you like, I’ll go back with you. You just want me to look wise?’

‘Exactly,’ assented Heldway. ‘Now can I use your phone for a moment? I want to talk to the Yard.’

When he put down the receiver he was whistling softly to himself.

The three men—Vernet, Heldway, and Fleeting—had travelled to Waterloo together, and there separated, the last named to Hatton Gardon, Heldway to Scotland Yard, and Vernet to keep an appointment. The demonstration was fixed to take place at noon.

Heldway’s business with the department did not keep him long, and when he left it was in a taxi-cab straight for Fleeting’s place of business. A couple of men were loitering in conversation outside the door, but as Heldway brushed by them they might have been perfect strangers to him instead of two of his most acute subordinates.

Fleeting was in a pessimistic mood.

‘I’ve got to make a decision today, one way or the other, Heldway. Unless you can prove something definite after Vernet’s experiment, I shall close the deal. He threatens to go to Burnett’s. You’ve not found out anything?’

‘Only that he’s a smart man,’ parried the detective evasively. ‘I’ll make a report to you after the demonstration. Meanwhile, I’d like to get up to the laboratory. Is there any place there where I can hide?’

‘Not room for a mouse,’ declared Fleeting. ‘I had it cleared specially.’

‘Then the outer room will have to do. Is there a cupboard or a curtain in that outer room anywhere, where I can be out of sight?’

‘There are heavy, long plush curtains to the windows. But why out of sight? I am sure Vernet would not object—in fact, I am certain he has guessed you are watching him in my interests.’

‘So am I,’ answered Heldway grimly. ‘But even if he guesses I am concealed, he will say nothing.’

‘I like that, you know. It shows he isn’t afraid of investigation.’

‘H’m!’ grunted Heldway.

Twelve o’clock was striking when Vernet entered, accompanied by Fleeting and a third man, whom the detective, watching from behind the curtain, guessed to be the expert searcher. Little time was wasted in preliminaries. The diamond-maker at once began to strip. The inevitable cigarette was still between his lips. The searcher made a slow, painstaking examination, and Vernet put on the suit which had been arranged for him.

He puffed out a cloud of blue smoke and stepped to the laboratory door.

Heldway flung back the curtain. ‘One moment, Mr Vernet,’ he said.

Vernet stood with one hand on the door, the other holding his cigarette. His eyebrows went up in well-bred surprise, and he made a little gesture of annoyance. ‘This isn’t quite fair, Fleeting. I asked you to take every precaution you wished, but I did think you’d be open and above-board—not set this man to spy—Oh!’

The detective had gripped his wrist. There was a second’s struggle, and then he staggered back from a quick push by the detective. Heldway had in his hand the broken fragments of the cigarette Vernet had been smoking. The diamond-maker had gone white. His fists clenched and his lips moved without speaking.

‘Look at that!’ exclaimed Heldway.

He had crumbled the cigarette into shreds. In the tobacco in the palm of his hand lay three rough diamonds.

It was then Vernet saw his opportunity. With a rapid movement he was at the door and, flinging it open, vanished before anyone could lift a finger to intercept him. ‘Never mind,’ said Heldway quietly, and lifting the window, he gave a long, low whistle.

He could see his two men arrange themselves one on each side of the door. One calmly stuck out a foot as Vernet emerged. The other caught him as he tripped. He was as helpless as a child in their hands. Not a word was spoken as he was marched with business-like haste back into the office.

‘Vernet,’ said Heldway, as he again confronted the trickster, ‘you will be charged with attempting to obtain money by means of a trick. You may volunteer any statement, but, remember, anything you say may be used against you. One of you two fetch a cab.’

Returning from the police station, Heldway accepted one of Fleeting’s choice cigars, and explained.

‘There are a lot of people,’ he said, ‘who believe that when you know a man’s guilty, all you’ve got to do is to arrest him. Those same people would raise Cain, of course, if one really did so. I believe Vernet was a wrong ’un from the start, but when you told me of your inquiries, I was not quite certain. He wasn’t in our records, nor could I find any of our men who recognised him. Of course I cabled to France and had a little investigation made there. The French police got hold of Vernet’s bankers, who assured them that he had last been in touch with their agents at Cairo. That was only five weeks ago.’