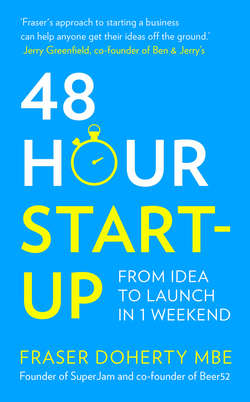

Читать книгу 48-Hour Start-up: From idea to launch in 1 weekend - Fraser MBE Doherty - Страница 9

ONE WEEKEND

Оглавление‘Is it possible to come up with an idea for a business and be up and running, selling a product to paying customers, all in the space of two days?’

This was the question that first started my journey with the 48-hour start-up, a slightly crazy experiment that I took on in the spring of 2016, without any real idea of what the outcome would be. I wanted to give it a shot, to see if the above challenge were possible to achieve, with all of the modern tools available to us entrepreneurs and by applying the many lessons I’ve learned so far in my exciting, challenging and at times downright bizarre career in business.

Throughout my adventures as a young entrepreneur, I’ve had the pleasure of speaking at literally hundreds of entrepreneur events around the world. No matter how different the culture of the host country might be from my own, I have always felt at home in the company of other entrepreneurs. We are a sort of dysfunctional global family of people who just happen to think the same sort of way – people who don’t want to work for someone else, but who want to make a mark on the world in our own particular way.

We’re a group of people who like coming up with ideas, sometimes inventing products that hitherto didn’t exist in the world. In my experience at least, we’re also a group of people who tend to feel that life is short – that we ought to make the most of every second we have. For all kinds of reasons, we see starting a business as the best way of doing that – an opportunity to make a career for ourselves, maybe work with our friends, do something we love and perhaps in some small way change the world. What more could you want from your work?

But something I have found on my travels in this community is that not all of the people who feel this way actually do act on their emotions. In fact, most of the people who harbour such feelings live their lives in a fashion that contradicts them – they hold down a job, study at university, work towards a rise, pay their mortgages and generally go along with the status quo.

THE CULT OF WANTREPRENEURSHIP

Everywhere I’ve gone on my trips, speaking at different entrepreneurship events, I’ve been aware of the legions of ‘wantrepreneurs’ who frequent such conferences. People who think a lot about starting a business – they attend the seminars, buy all the books, even meet with successful entrepreneurs to ask for advice … but they never actually start.

Perhaps they don’t start out of fear of failure or maybe they just procrastinate, putting things off for another day. I am sure a lot of them are waiting for the ‘perfect idea’, which will never really come. They’re always telling their friends about the idea-of-the-week, never giving enough focus to one idea for it to become anything close to a reality.

Far too often, wantrepreneurs will inhibit this very healthy process by keeping their ideas all bottled up to themselves, never even so much as sharing them with anyone – let alone actually getting them onto the market. I think this is all such a tragedy – no doubt all kinds of ideas don’t make it into the world and, more importantly, so many people don’t get the chance of taking them there.

Maybe some of these justifications for inaction sound familiar … and I don’t want to be the one who says it but maybe, just maybe, the phrase ‘wantrepreneur’ applies to you. But don’t worry, it’s a very curable disease. I can assure you that if you’re willing to take action then it’s not a phrase that will describe you for much longer.

TELL EVERYONE YOUR IDEAS

There’s something that, for me, absolutely sums up the wantrepreneur mentality. Quite often, at the end of one of my talks, people will come up to me and introduce themselves. They’ll say, ‘Hey, I have an idea for a business,’ and I’ll say, ‘Oh, great, what’s your idea?’ … ‘Oh no, I can’t tell you that … what if you steal it?’ they’ll shriek.

Not only is this kinda funny, I think it is totally upside down. In my mind, if you have an idea for a business, especially if it’s a half-baked one, you should tell anyone who’ll listen – you never know which person might help you. They might give you some useful feedback or introduce you to someone who works in your industry or if you’re very lucky, point you in the direction of a willing customer.

Because people keep their cards close to their chests in this slightly misguided way, I never do get to hear all of these ideas. I should probably be careful what I say because, for all I know, some of these people I’ve met are working on truly revolutionary, paradigm-shifting, world-changing innovations. The chances are, however, that they’re not.

And that’s not just me being mean. I’m sure you’re well aware that the likelihood of any idea going anywhere is pretty slim – most new businesses barely make it off the starting blocks and, more often than not, the ones that do are destined to fail.

So, in light of the terrible odds facing these bright-eyed entrepreneurs, the chances of their businesses making it are, at least in my opinion, even more slim. If their ideas haven’t so much as had the oxygen of discussion, they really don’t stand a fighting chance.

PESSIMISM AND OPTIMISM

Ideas are extremely precious little things. You can absolutely assume that the first incarnation of any idea is completely wrong – that it needs more bashing about, further iterations, until it actually makes sense. I sometimes think that the perfect environment for an idea to succeed is one with equal parts of blind optimism and honest pessimism.

Let me explain what I mean by this. First off, there’s definitely a need for a little bit of blind faith in the recipe of what makes an idea succeed. If you analyse any idea enough, you’ll soon put yourself off starting it at all. The thing is that most ideas don’t make a lot of sense in the beginning. It’s only by having the faith of actually getting them going and learning as you go that you’ll wind up hitting upon a model that works.

Because of this, you need to have a bit of faith – throw yourself completely into your idea even if it isn’t all perfectly mapped out at the start. So many wantrepreneurs are waiting to complete a business plan or do more market research – the truth is that your idea will never be perfectly formed before it gets out into the world. Basically, you just need to start.

Coupled with this faith, you need your idea to go through a bit of a beating. If nothing else, you need to talk to a few people to be sure that you’re not completely crazy … or at least that your idea isn’t. You will be tempted to simply ask your family and friends what they think, but the fact is that they aren’t really going to give you impartial advice – they love you too much to tell you honestly if your idea stinks.

So, you need to try running your idea past some people who have been there and done it before or some people who are inside your chosen industry who know what they’re talking about. You need to find some people who aren’t afraid of hurting your feelings, people who don’t have any kind of vested interest in you or your idea.

This process doesn’t need to take a lot of time and, of course, later in the book we will talk about some of the ways that you can find this critique very quickly. If you can muster up enough optimism to throw yourself wholeheartedly into your idea and also find some pessimists to help bash it into shape, your little caterpillar of a concept might well grow into a beautiful butterfly.

Of course, some of your ideas will be beaten to death by pessimism – and perhaps quite rightly. Never be too pig-headed to change your idea or change your mind. If all the advice comes back as a thumbs-down, maybe consider your other options.

No matter how many ideas you have to go through, the most important thing is that you maintain your optimism. I guarantee that if you do that, eventually you’ll make a start and you’ll graduate from wantrepreneur to entrepreneur.

MY START AS AN ENTREPRENEUR

In my case, I always wanted to be an entrepreneur, perhaps from an unusually young age. I’m not exactly sure where it started but I was always making things and selling thing to the neighbours.

My earliest memory of trying to make money was from when I was about eight years old. I baked some cakes and sold them to my teachers at school. I sent the money that I made to Greenpeace, my favourite charity at the time. By ten, my entrepreneurial ambitions had grown and I was fascinated by the simple businesses that I came across as a child on the outskirts of my home town of Edinburgh. I visited a local chicken farm with a childhood friend. ‘What a great business!’ I thought: the farmer just has to feed the chickens, they lay eggs, and he can carefully steal them to sell for a profit, without having to share any of the takings with his feathered employees. Bingo!

We convinced the farmer to give us a box of eggs for free, which I took home to my mum and dad and explained that we’d had this brilliant business idea. We would keep the eggs warm so that they would hatch and then sell the eggs that the resulting brood of chickens would lay!

As I’m sure you can imagine, my parents weren’t particularly keen on this business idea – of turning their suburban back garden into a chicken farm! Fairly used to my hare-brained schemes by this point, however, they let us give it a shot, not really expecting two ten-year-old boys could find a way of hatching eggs.

And so we put the eggs on top of the cable TV box under the telly, where it was kind of warm. And, amazingly, three weeks later, four of the eggs hatched into little chickens. The poor things probably thought that Jerry Springer was their mum!

We raised the chickens in the house, gave them names, and soon they were big enough to go out into a house my dad built for them in the garden. Before long, they were laying eggs, which we sold to the neighbours.

Unfortunately, my chicken farming career was sadly cut short one afternoon when the local fox decided to eat the chickens for dinner! I guess you could say that I learned my first real lesson as an entrepreneur – that, at the absolute least, you should look for a business idea that doesn’t have any natural predators!

As I’m sure you can tell by this point, my beloved parents were very supportive of my no doubt exhausting entrepreneurial energy as a child. My interests baffled them, and everyone around us. Neither of my parents nor anyone we knew had ever started a business before – where this interest came from was something of a mystery.

FROM EGGS TO BACON

It wasn’t long before I met an entrepreneur for the first time. One of my high school friends had a job as a ‘bacon boy’, selling bacon and sausages door to door. He told me about how he was paid 30p commission for each packet of bacon that he sold. I was instantly hooked – where could I sign up?

My friend explained that since I was only 12 this would be a problem – I would have to pretend that I was 13. ‘No problem,’ I exclaimed. And so it was arranged that my friend would introduce me to the boss – The Bacon Man, a Mr Alan Bryson. Despite my naïvety and perhaps the insincerity of some of my answers, I got the job, and within days we were pounding the concrete, knocking on doors all over the neighbourhood.

It didn’t take long for me to build up a list of regular customers. I would walk miles every evening after school, proudly wearing my white uniform and always trying to improve my pitch. In the beginning I was selling maybe 20 packets a week, but gradually I found myself close to breaking the 50-packet-a-week mark.

TEENAGED COMPETITION

The Bacon Man published a weekly newsletter for his fifty or so teenaged, spotty sales reps. He would include motivational quotes – ‘If you fail to plan, you should plan to fail,’ that sort of thing – along with a ‘Top 10’ table of who had grossed the most sales that week.

A few months into the job, I found myself published in the top ten for the first time. My sense of achievement was immense – I had grown my delivery route to include all of the well-to-do neighbourhoods in the west of Edinburgh. It wasn’t an easy job and I worked hard at it. I would walk down vast driveways in the rain, only to be told that the owners were Muslim, Jewish, on holiday, on a diet or just didn’t have any money to hand.

Eventually, at around 60 packets sold in one week, I found myself in second place with another boy. His name was Richard Field; I can remember his name to this day. He had beaten me by only a few packs – next week I was resolved to top the charts.

But I quickly learned that he wasn’t going to give up the top spot easily, and so found myself engaged in a spate of competitive bacon selling.

Our weekly totals rapidly touched 80 packets apiece and continued to climb. One week he would have the top spot; the next it would be mine. Eventually, partly thanks to the modest innovation of doing my round by bicycle instead of on foot, I managed to overtake him for good. This competition resulted in an achievement I still feel a twinge of pride over: I became the first Bacon Boy to sell 100 packets in a week!

Impressed by my accomplishment, the Bacon Man asked me to become his new right-hand man. I was 13 years old and nobody so young had been granted such an honour before. The deal was that he’d pick me up from school in his van and drop me off in an area of town I’d never been to. I’d be given an under-performing Bacon Boy and it would be my task to get them up to speed.

What a wonderful job, I thought. And that wasn’t all: I’d be paid the incredible sum of £20 a day. An unheard-of amount among the kids of our playground.

‘Sounds great!’ I thought. ‘No way!’ my parents shrieked. Whether they didn’t like the idea of me wandering through the wrong parts of town in the dark, or were concerned that all this extracurricular bacon selling would affect my studies, I’m not sure, but my parents’ reservations stood no chance against my enthusiasm, and I was soon selling bacon wherever it needed to be sold. The Bacon Man taught me everything he knew. He was truly an archetypal entrepreneur – a man who saw an opportunity and went for it, regardless of how unconventional a business model it no doubt appeared to his friends when he first started ‘The Bacon Service’.

He taught me the basics of customer service. He would go crazy if he found out that a Bacon Boy hadn’t been doing his ‘call backs’. This was where you would have to walk back to a house of one of your regular customers at the end of your round – if they had been out the first time you called. Of course, this was a total pain in the ass, especially if they were still out the second time around.

But the lesson he taught me was that if you didn’t get hold of your customer, you had let them down. Some, for example, were old ladies who counted on your delivery each week. They would often have the correct change all ready for you. If they had popped out to the post-box and ended up missing their bacon that week, there was a risk they’d buy a multipack at the supermarket instead and you would lose them forever.

KEEP ON KNOCKING

The bacon-selling job was a truly formative experience, and the attitude it pressed into me has had an impact on me to this day.

There is no more physically exhausting and mentally gruelling way to sell a product than by going door to door with it piled high in a plastic bucket. At least if you do telesales you have a seat.

Add to that the fact that there can’t be many more unpleasant climates in which to go door-to-door selling than the one we have here in Scotland. For the most part, it was so cold outside that the bacon we were selling needed no further refrigeration!

Our customers were Scottish housewives – a thrifty bunch who knew the prices of equivalent products in the supermarket only too well. It’s safe to say that a Bacon Boy faces more than his fair share of rejection on his rounds.

We would knock on nine doors before the tenth might say ‘yes’, taking a packet from our shivering hands and replacing it with a few coins. At first, being rejected over and over again was hard to take. But in the end I came to accept that as a Bacon Boy, just as in life, you have to knock on thousands of doors, each time with the same enthusiasm as the last. For the most part, anyone’s career as an entrepreneur is a sea of rejection, peppered with the occasional hard-won sale. A process of trying something, failing, changing tack a little and trying again. This is natural.

My youthful sales experience provided me with a great education. I was totally captivated by the whole world of starting a business – amazed that through nothing more than walking the streets, pressing doorbells and talking to people, I could build a business out of thin air, despite my being a teenager who knew nothing about anything. I could secure hundreds of regular customers and even grow my little enterprise week on week, simply by doing a good job.

Remember, at the start of your 48-hour journey, the importance of starting small. There is no shame in launching a product on a tiny scale – at a farmers’ market, or by picking up the phone, or, heaven forbid, knocking on doors.

In the end, despite my fondness for the Bacon Man and the lessons he was teaching me, I had a burning desire to ‘stick it to the Man’. Why was I spending my life working for someone else when I now knew how to do it on my own?

The urge towards self-employment overtook me and I soon resigned from the Bacon Service, telling the boss I would be striking out on my own. Entrepreneurship had come knocking.

BE WILLING TO TRY

All of these early experiences as a kid really shaped my attitude in business to this day. I was very lucky to have parents who stressed to my brother Connor and me that the most important thing in life was to find something that we loved – that to get up in the morning and do something you enjoy is success. They never tried to push us into a particular direction and always supported us, no matter how bizarre our dreams at the time might have been.

Looking back, I’m amazed that my parents showed such patience throughout my eccentric childhood attempts at making money. I’ve come to learn as an adult that most parents wouldn’t have put up with such things. They tend not to let their kids raise farmyard animals in the family home. Fair enough, I suppose. More seriously, they typically tell kids that their ideas won’t work. They short-circuit the process – rather than letting their kids learn from trying and failing, they’d rather they didn’t try at all.

Through the Bacon Man I gained a basic understanding of what it meant to be an entrepreneur. He was someone who approached life on his own terms, and actually enjoyed what he did, almost obsessively so.

Thanks to his bacon empire, he was able to go on three or four holidays a year and, at least by my calculations as a naïve teenager, he barely had to do any work – the grunt work (excuse the pun) was done by his loyal teenaged followers.

Thanks to my slightly unconventional childhood, my life has been one of hundreds of small business failures and a few successes. I’ve attempted all kinds of ideas over the years, and most of them didn’t work.

Throughout my teens, I tried more than I care to remember. Most I have tried to banish from my mind, having wasted months on them barking up the wrong tree. Some memorable experiences include an attempt to redesign nappies so that they could be flushed down the toilet rather than sent to landfill, a business selling bars of chocolate with teachers’ faces printed on them, and a company distributing biodegradable plastic cups to outdoor events. I made websites for people, printed funny T-shirts and even brewed my own beer. In my twenties I tried various other ventures – delivering healthy meals for the elderly; creating a last-minute high-end restaurant booking app; launching a healthy food subscription business – and invested my savings in all kinds of other people’s start-up ideas, most of which didn’t make a return.

When I ask people what they think of all of this, they usually reflect on how I have been able to bounce from one failure to the next, without losing enthusiasm for the overall project of being an entrepreneur. My parents always seemed delighted, if not a little puzzled, that, even when I was a child, within days of giving up one unsuccessful concept I would already be working on some other idea that I was convinced would change the world. This, I believe, is because I am not afraid of giving ideas a shot, even if there is a high possibility of failure. I absolutely have my parents to thank for that – for never discouraging me from trying.

MY FIRST WEEKEND AS AN ENTREPRENEUR

You may already know a little about my SuperJam story from my earlier book, SuperBusiness, in which I shared the adventure that I went on ‘from my gran’s kitchen to the supermarket shelves and beyond’.

After my short career with The Bacon Service, I found myself looking everywhere for a new business idea and then, one afternoon, my grandmother was making jam in her kitchen in Glasgow, just as she had for as long as I can remember. Eureka! Jam would be my product.

We made a few jars together, Gran sharing her jam-making secrets with me, and then, bursting with enthusiasm, I raced to the supermarket to buy some fruit to make a few jars of my own. While the fruit was boiling I printed some labels on the computer at home, under the imaginative-enough brand name ‘Doherty’s Preserves’. I adorned the jars with a little strip of tartan ribbon, stolen from my mum’s sewing box.

Before the bubbling jam with which I had filled the odd-shaped jars had even cooled down, I headed out to the streets with a dozen or so loaded into a plastic bucket. I strained under the weight of them as I walked from house to house. Almost everyone said no, but eventually a kind old lady who knew me from my days of selling bacon bought a jar. I was in business!

I could barely contain my excitement as she counted out her £1.80 in small coins into my hand. I no doubt beamed with enthusiasm as I knocked on door after door after door that cold Scottish evening. An hour or two later I returned to my parents, proudly holding the plastic bucket upside down over my head – I was triumphant! Before long, my success was such that the Edinburgh Evening News ran a story about me at 15 years old.

From that point on, jam completely took over my life, to the point that I decided to leave school and go full time into making it. I’m not sure whether my parents thought it would truly become my career, but they could see I was doing something I loved, and that was what mattered.

I was soon making jam every day, selling it at farmers’ markets all over Scotland. I constantly tweaked my recipes, learning from customers as they gave me feedback on the previous weeks’ batch. A lot of people told me that they didn’t eat jam because it has so much sugar in it. This simple market feedback gave me an idea. What if I could create a recipe for jam that was made 100 per cent from fruit? And so I experimented in the kitchen for months and months, trying everything I could think of – making jam completely from fruit, with honey instead of sugar, until eventually I settled on a combination of fruit and fruit juice.

It became my dream to sell my latest idea – which I quickly named SuperJam – to the major supermarkets. I convinced my dad to drive me to the head office of Waitrose, having heard that they host special events called ‘Meet the Buyer Days’, where hundreds of people show up, brandishing their homemade cakes and soups and sauces. Everyone gets ten minutes to pitch their idea, in my case to the ‘Senior Jam Buyer’ – I bet you had no idea that such a job title existed!

While my dad waited in the car outside, I told the buyer all about my idea for making jam 100 per cent from fruit. He said it was an excellent idea and a lot of fun to see a 16-year-old boy presenting it. (I’d borrowed my dad’s suit for the occasion, probably two sizes too big for me, which no doubt provided the buyer with some amusement!)

Although he liked my jam, he told me very straightforwardly that the business idea is only a small part of the equation of what makes a product a success. He explained that I would have to set up production in a factory and offer him a good price. I’d have to get labels designed that explained to people why they should buy my products. And I’d have to do a bit more work on my recipes before he’d be happy.

This was my biggest rejection to date. I should have learned by then that the first time I knocked on the door of a big supermarket, they probably wouldn’t say yes. I was totally bummed out for I had absolutely no idea how to create a brand and set up production in a factory.

LESSONS LEARNED

While I had managed to start the first incarnation of my jam business quite literally in a weekend, with little more than a wooden spoon and a big helping of teenaged optimism, the next step wasn’t going to happen so fast. The task of creating a ‘real business’, a product that genuinely had the potential to make it big, seemed insurmountable. And such fears seemed confirmed when I returned to the buyer a year later to meet with another rejection. The buyer explained that the labels I had created were too silly, the factory too expensive and my recipes too unusual. Basically, I’d got everything wrong and had to start all over again!

Although I was totally devastated, I had come to accept that rejection would always be a big part of this process. I also learned that while family and friends are an extremely important source of help and support, they’re not able to give impartial advice. When they see you fail, they hate to see you get hurt and so would rather that you stopped. The person you should actually listen to, and I know it sounds cheesy, is the customer. In my case, even though I had done everything wrong, the buyer still felt that I had a good idea.

If everyone tells you that your idea stinks, including customers, you should probably reassess whether or not it is the right thing to be doing with your life. But if customers still maintain that your idea is something they’d be interested in buying, there’s a good chance that you should keep going. That glimmer of hope helped me to persevere.

And thank God, because it did turn out to be a good idea. By the time I redesigned the labels and convinced a new factory to work with me, the supermarket said ‘Yes’, and before long we had launched in more than 1,000 stores around the world and SuperJam was entered into the National Museum of Scotland as an example of an ‘Iconic Scottish Brand’.

A personal highlight of my adventure was seeing SuperJam become something of a phenomenon in South Korea. For my grandmother the biggest day out was our visit to Buckingham Palace, where we were presented with a medal by Prince Charles. But what I enjoyed most was seeing my life story made into a TV drama in Japan. In the dramatised re-enactment, I was played by a small Indian boy – something, presumably, was lost in translation, but never mind!

SuperJam has been something of an adventure and a success, but I can’t help wondering sometimes how much more quickly it could all have been achieved. During the process, I found that every facet of setting up a real business was new to me. I had no idea how to create a brand, how to work out the finances or anything else. I really knew nothing, and had to figure it all out as I went along, taking many a wrong turn and wasting priceless months as I did.

Of course, when I came to apply lessons learned to my second business and then to my third, the whole process became a lot quicker – I simply didn’t make the same mistakes again.

ENVELOPE COFFEE

One of my best friends is Lennart Clerkx; he’s Dutch, and a pretty interesting guy – able to speak seven languages. But one of the things that is a little unusual about him is that he doesn’t have any sense of smell. That’s a serious affliction. However, it’s not all bad news. Just as those who are blind sometimes have extra good hearing to sort of compensate, so Lennie has unusually good taste buds. He can pick up on the acidity or sweetness of what he’s eating better than most people.

He discovered that he had this particular talent, and subsequently became interested in coffee, when he was living in Denmark, where some of the world’s most pioneering roasters are based. Now, he’s made a whole career out of his taste buds.

Coffee roasters from around Europe send him to Africa, and Central and South America, in search of the best beans. He can tell better than anyone how acidic or sweet a particular harvest is. He’s also all about paying the growers a fair price for these incredible beans that he discovers. His company, This Side Up, helps small roasters buy beans from these far-flung places, directly from the farmers.

Not long after we first met, sharing a beer by a canal, Lennie told me all about his travels in the developing world and I became instantly fascinated. He showed me photos of the places he’d visited and told me about the lives of the farmers. More than anything, he was evangelical about how great their coffees were.

On another weekend visit to see him in Amsterdam, and no doubt after a few more beers, we decided there was a better way to do the coffee business. Why didn’t we buy the beans directly from the farmers, using Lennie’s connections, and then sell the roasted coffee directly to customers over the internet? No middlemen, no importers and no supermarkets between our customers and the people growing these incredible beans.

Within a matter of days I had come up with the name ‘Envelope Coffee’. I’d found a local coffee roaster in Glasgow who could roast and pack the beans for us and had set up a simple website to charge our customers a fortnightly subscription.

Using a list of ethically sourced beans from countries such as Rwanda and Ecuador, we soon had a product to sell. We used standard coffee envelopes, which we ordered inexpensively online, but made them look great by creating a nice label for them.

I invited a Danish photographer, Kiva Brynaa, to London to shoot the product in situ at a coffee roaster’s premises over the course of a half-day. Even though the company had been started on a shoestring in a matter of days, I wanted our customers to get the best possible impression of us. In my opinion, brilliant photography can ensure this in a way that nothing else can. I really believe that foods – especially things like coffee – are visual products. We eat with our eyes.

Within weeks of having the idea for Envelope Coffee, we sold our first bag of coffee. And it didn’t take long before we had a loyal base of subscribers – the product truly spoke for itself. Besides, coffee is a pretty addictive product – when you find one you like, you stick with it.

Buoyed by one another’s enthusiasm for the project, within weeks Lennie and I were on a flight to Colombia to find our beans. We took another Danish friend, Nick Levin, a photographer and filmmaker, to shoot a short movie about Colombian coffee.

Over there, they grow some of the best coffee in the world and they’re very proud of it. After a night in the big city of Bogotá, we headed to the countryside. When we got there, we spent some time with Juan Pablo, one of Colombia’s foremost coffee experts – a man who tastes more than 600 cups of coffee … a day!

While we were waiting for a sample batch of beans to roast in a tiny roaster, I asked him what he drank on his breaks, which I meant as a joke. ‘Oh, coffee,’ he said, with an air of bemusement. He drank up to 16 cups of coffee when he wasn’t at work. He later told us that he got all of two hours’ sleep a night – and that the rest of the time he was thinking about coffee.

This guy was full of energy. And in his office, with him, we tasted more than 100 of the best coffees from around Colombia. We found one that we particularly loved – it was perfect for what we were looking for. So we decided that we would shake hands with the farmer, cut out the middlemen and buy the coffee directly from him. A simple idea, or so we thought.

We soon found ourselves in an unfamiliar country about which we had heard all kinds of horror stories. Two flights into the Andes later and an eight-hour drive along a treacherous cliff-face of a road, we found ourselves in the most beautiful little village I’ve ever seen. It was situated 1,200 metres above sea level – very high up in the mountains. The village was at the foot of a volcano, so the soil was incredibly fertile, perfect for growing coffee. The fruit was falling out of the trees and there was coffee growing everywhere – Lennie was in coffee heaven!

There were over 1,000 people living in the village, all completely reliant on the coffee harvest for their livelihoods. And they were very happy to see us. Until relatively recently the area hadn’t been safe enough for international coffee buyers like us to visit – mostly because of cocaine production, smuggling and guerrilla activity endemic to the area.

But now it was safe for people like us to explore the fields, and the farmers showed us their plots with pride. We found a particular farm that we really liked – the plants were very well taken care of, with plenty of shade, and the family who owned them were wonderful. We stayed in their home for a few days and enjoyed eating the local cuisine – although we did turn down their offer of barbecued guinea-pig.

In the end, we bought their beans and shipped them to Scotland for roasting. Not only did we have some of the world’s best coffee on our hands, we also had this great story to tell about the people we’d bought it from and the beautiful place where they’d grown it.

I was so confident that people would like our coffee that we offered anyone their first bag ‘on the house’. I placed vouchers in hundreds of thousands of magazines that I thought the right kind of people would buy. We rewarded customers who shared our offer with their friends.

Over the course of a few months, around 10,000 coffee-lovers signed up for our club. The reviews for our Colombian coffee were outstanding. Our business soon attracted the attention of a larger competitor, who offered to buy us out.

By this point, my own time was so stretched between SuperJam and other projects that this seemed like the best option. I wasn’t putting the kind of time into Envelope that would be needed to take it from a lifestyle business into a ‘real company’. I was, however, very proud of this fantastic product that we made.

I definitely now believe in the importance of focusing on one idea at a time. As entrepreneurs, it’s easy to be like a magpie. Always distracted by the latest shiny idea.

What amazed me about this experience of starting Envelope was that I managed to go from having an idea with my friend in the pub to having a great product in people’s hands in a remarkably short space of time. Not only had we done it fast, we’d also done it well. Anyone looking at our site wouldn’t have thought the company has been started in only a few weeks – our photography was beautiful, our packaging was just as good as any of our competitors’ and, most importantly, the product was delicious.

BEER52

A similar business that I was involved in starting is Beer52, a craft beer club. My now business partner James Brown had been on a motorcycle road trip around Europe with his dad, during which they’d stopped at craft beer bars and breweries, refreshing themselves along the way.

The way I tell that makes it sound like they were drink-driving but I promise you they weren’t!

This trip ignited James’s passion for craft beer and on his return to Scotland he started to learn more and more about the beers and breweries he had found on his trip. With the help of some quick internet research, he learned that there are more than 14,000 microbreweries in the world. They are literally popping up everywhere, with new ones opening every week. The craft beer trend is a well-documented success story all over the world.

But with so many breweries out there, how could anyone even begin to discover the best ones? Most of them are just selling in their local area on a small scale.

James decided that he wanted to do something about this – create a way for people to discover some of these great beers and also a way for the breweries to get their beers out to a wider audience.

We met up and threw some ideas around. Wouldn’t it be cool to make a sort of tasting club, we figured. We could ring up breweries and ask for samples, then together we could have fun tasting the hundreds of bottles that came in and pick the best ones. Once we’d figured out which were the best, we’d order a whole batch to send out to our members. Sounds like a fun business!

And so the idea for Beer52 was born. We would produce a monthly selection of craft beers from around the world and deliver a mixed case of bottles directly to our customers’ doors. They’d pay a monthly subscription to be in the club and we’d produce tasting notes and content about the beers, so that people could learn all about what they were drinking.

Selling beer on the internet

Neither of us really knew how to build a full-on subscription website from scratch, but the great thing was that we didn’t have to. We used a service called Shopify to make a very simple website (there are lots of these services available, so check out which one is best for you).

We hired a freelance designer to create a simple logo, then mocked up an example of how we wanted our boxes to look and booked a photographer to create some images for the site. Within almost no time we had gone from having an idea to creating a website that gave the impression we were an established brand.

With the basic building blocks in place, we immediately started calling up breweries to ask if they’d sell us, say, 100 bottles of beer for us to send out in our deliveries to our customers. For the most part, they didn’t return our calls. It wasn’t a large enough size of order for them.

So we tried a different angle. We rang breweries and asked if they would send us 1,000 bottles of their beer for free. In return, we’d get it out into the hands of people who love craft beer. The breweries found these kinds of numbers much more exciting and agreed to give it a shot.

Samples started arriving within days and we had the oh-so-difficult task of deciding which were our favourites to put into our inaugural selection box. We arranged for the beer to be delivered to a third-party fulfilment centre – a place that had the ability to store and pack our orders as they came through, simply charging us a small fee for each one that went out the door.

In the end, we produced 1,500 cases for our launch. It was a bold move but we knew that for a subscription business we would need to attract a critical mass of members – only some of those who took up our initial offer would go on to become loyal members.

To attract this initial critical mass we knew we would have to do something more than just hand out some fliers in the street; it would take a bolder and more unconventional initiative to get 1,500 people to sign up for our club in the first month. We came up with the idea of using Groupon.

Normally, people would say that using a discount website to launch your business amounts to suicide. Surely that’s the sort of place that great brands go to face their deaths, not their births.

But the way we saw it was that there was no better way to get our launch into the email inboxes of millions of people from day one. By giving them a special deal on their first box – just £9 instead of the usual £24, hopefully a large number of people would take it up. And, assuming our product was any good, hopefully enough would stay into the following month to pay full price.

The deal launched. Within 40 minutes we had sold out of beer. We were so excited and the people at Groupon were too – they’d never sold beer before on their site so perhaps we had helped them to discover a whole new category of opportunity. Now all we had to do was to send the orders across to the warehouse to be shipped to our customers.

If only it were that simple – we had never shipped glass bottles of beer before and hadn’t thoroughly tested our packaging, in our rush to get our product to market. Within days we were flooded with hundreds of complaints – about a third of the packages had arrived smashed at our customers’ doors. Not really an ideal way for our brand to introduce itself to the world.

In the end we replaced all of the broken bottles and refunded those customers. A lot of them were so impressed by how we handled the problem that they’ve stayed with us to this day. We went on to improve our packaging and have since seen more than 100,000 members join our club.

We’ve sold many millions of bottles of beer and worked with hundreds of the most pioneering breweries from around the world. Our magazine, Ferment, is the largest-circulation publication on craft beer in the country and we’ve been able to raise investment to launch our brand internationally.

I think what made this business work was that we just ran with an idea. We didn’t sit around planning things out perfectly – we just picked up the phone to breweries and tried to sell them our concept. When they didn’t like our initial idea, we changed it instantly.

Sure, when we launched it wasn’t plain sailing but we did go from zero to over 1,000 customers in a day. As the business has developed, we’ve continued to apply these same principles. We’re constantly testing ideas very fast and on very small budgets. If things work, we scale them up. If they don’t, we scrap them and move on.

Human behaviour

Another one of the reasons for Beer52’s success is that we used a business model that fitted well with our customers’ natural habits. I know in my own life that if I sign up for a subscription, unless I don’t like what I’m being sent, I am usually happy just to let it run and run.

If our customers had to come to our website every month to place an order, they’d probably buy less on average than if they have a subscription set up. Partly because they share my laziness but also because a subscription can be a really convenient way of receiving a regular supply of something you enjoy, especially if it’s something as easily consumed as beer!

Beer52’s customers have a high lifetime value, because when someone signs up they’re not just buying one box of beer; they’re typically subscribing for a large number of months. Thanks to this, we can spend a lot of money on marketing upfront to attract customers to sign up in the first place.

YOU AREN’T ALONE

What we’ve learned is that it’s possible to have an idea in the pub one night and develop it into a business the next, with a credible website registered to a catchy domain name for all the world to see. This can all be done extremely quickly – and that means by the competition as much as by you.

A phenomenon that I’ve observed countless times is that whenever we’ve been working on a new idea – one that we thought was totally original – we weren’t alone. Someone else in the world has read the same articles, maybe has the same interests and has started thinking about how to solve the same problems.

Often, products come to market at almost the same time, and one looks like a carbon copy of the other. Sometimes they are exactly that – a fast-follower – but quite often they’re part of this phenomenon of simultaneous invention. With all of our ideas – our beer club, our coffee club and many of the new products that we have presented to retailers through SuperJam – the competition has created exactly the same concepts at or around the same time.

The idea of a craft beer club didn’t exist a few years ago but at the last count there were more than ten in the UK alone, all started within a short space of each other. While we’re by far the largest, there are certainly a lot of upstarts following fast on our heels.

It’s my belief that, in this environment, our only defence is to move more quickly than the rest. Whatever your idea is, the chances are that someone else is already working on it. So if you can give yourself a head start by getting off the ground first, that could make all the difference between success and failure. There’s nothing worse than planning your idea for months and months only to be pipped to the post by someone launching their version before you.

STARTING UP FAST

Especially during my time creating SuperJam, I had a lot of ups and downs, and there were plenty of times when I reached a dead end and thought of giving up. With Envelope and Beer52, there were also steep learning curves – all kinds of things that I didn’t know about selling online and creating internet businesses.

But each time I have set up a business, the process has got faster and faster. I’ve learned that even if the products you are trying to sell are completely different, many of the processes you need to go through are exactly the same.

Having done things the ‘hard way’, I wondered whether it was possible to short-circuit the lengthy process of coming up with a successful product and bringing it to market. I wanted to see if I could get something off the ground and have money coming through the checkout at lightning speed, ideally in just two days, from a starting point of nothing.

Based on the mistakes I’d made while growing SuperJam and starting other businesses, I knew there must be an easier way of doing things. Over those ten years, I had figured out how to outsource manufacturing, get great design work produced, handle customer service and arrange photo-shoots, and had learned all kinds of other bits and pieces necessary for creating a business. All things that I didn’t study beforehand but that I figured out through trial and error.

SHOESTRING BUDGETS

Starting a business can be an incredibly expensive process. That’s if you do things the conventional way. By the time you pay for designers, lawyers, accountants, stock, printing, web development, domain names and office space, I’d be surprised if you had any change left out of ten grand.

And that’s money down the drain before a penny has even gone through the checkout. If your business idea proves unsuccessful, you stand to lose a huge amount of money.

I wondered whether there might be a smarter way of doing these things – a way to avoid many of the normal costs involved in starting a business. If so, that would mean it was no longer such a big deal if it didn’t work – you could just go back to the drawing board and try something else, armed with the lessons you’ve learned from your first idea failing.

Ideally, I wanted to take an idea to market for a few hundred pounds – not because I don’t have more capital at my disposal, but because I wanted to show that it could be done. If you can start a business for such a small amount of money, surely that would mean that anybody could do it?

Very often, wantrepreneurs use a ‘lack of capital’ as a scapegoat for not starting their business right away. They create vast shopping lists of all the things they believe they need – an office, a world-class design agency to create their brand, an all-singing-all-dancing website. Surely you don’t need all those things to at least get a product onto the market?

THE 48-HOUR START-UP

Despite wanting to ‘bootstrap’ my 48-hour start-up and build a website for very little money, it was important to me that it was still well designed and professional. Most of all, my product would have to be a good one that people would actually want to buy. There is definitely a bare minimum in terms of design and quality that your product needs to achieve.

Starting a new business has to be something that creatively is an exciting project to work on, otherwise what’s the point? Besides, if you’re not working on something you love, then when the going gets tough you’ll quit at the first hurdle.

Given that I have previously launched products that hundreds of thousands of people have loved, this new start-up would have to be of the same calibre – I wanted it to make people go ‘wow’. Otherwise, perhaps, it would be what musicians call ‘the dreaded second album’; my peers would have an expectation of what sort of business I might start, and if it fell short of that it wouldn’t look so good. I’m sure that you too want any business you build to be something you can be proud to show your friends.

Most of all, however, I needed to create a business model that would require a minimum amount of input from me in the months and years that followed its creation, because of my existing business commitments.

I wanted to find a way for the business to be outsourced, streamlined and automated. After a customer placed an order, I wanted the whole process to be handled without any input on my part. The order would be placed online, sent to a third-party warehouse for packing, and then delivered to the customer by courier.

Rather than using expensive design agencies, I found inexpensive freelancers online who were willing to create my branding and advertising for a fraction of the cost. Using highly measurable forms of marketing, such as Google AdWords, I was able to promote my start-up on a tiny budget, knowing that for every pound I spent on marketing, a new customer would click ‘buy’.

Using this ‘virtual’ business model, where the company has no premises or staff of its own and only uses forms of marketing that can be measured and automated, the business could be extremely scalable – it wouldn’t be limited by the amount of time that I could invest in it.

Very often, people feel their idea has to be perfect right from the start. Actually, I am a huge believer in making a simple version of your concept that is ‘good enough’ and just getting going, making changes and improvements on the fly.

Rather than spending weeks trying to come up with the perfect name, you’ll pick one that does the trick in a matter of minutes. Instead of creating a brand that is a work of art, spending tens of thousands of dollars along the way, you will be happy to pay someone a few hundred dollars to create something that helps you bring in your first few customers, maybe investing in improvements in the future when you can more easily afford to.

A NEW ERA

What’s really cool is that we are at the advent of a new dawn of entrepreneurship. While it used to cost huge amounts of money and take months to start a new business, the internet and the new tools that it brings have increasingly made it possible for anyone to start a business in their bedroom that competes with the biggest companies of the day, for almost no money.

You need little more than an idea and a willingness to give it a shot. This is such a revolution that thousands of people are starting businesses from the comfort of their own homes every week. They’re fortunate enough to be making a living out of doing what they love – something that just wasn’t possible even a few years ago.

The cost of starting a business has been driven through the floor by online tools and marketplaces that help first-time entrepreneurs find freelancers, products and customers in a matter of clicks.

Services like Shopify allow you to get a professional website online in hours, for no upfront cost and just a low monthly fee. Upwork (formerly oDesk) and various skills marketplaces put you in touch with freelance designers, writers, marketers and developers, bypassing expensive agencies with their flashy city-centre offices. Moo allows you to design your own printed materials online and turn around hard copies in a day.

All of these tools, and more, make it possible for anyone to get an idea out of their head and into the world in a matter of days. Now you have no excuse for not at least giving it a shot – what have you got to lose?

START FOR YOUR OWN REASONS

Starting a business can be whatever you want it to be. Some people start one as a way to get rich – and that’s fine. But, for me, what’s more exciting is the idea that you can start with a blank page and go on to create something wonderful; something that makes the world a different place. You may even create a product that ultimately will give enjoyment to hundreds of thousands of people.

It is also possible to use your business to further causes that you feel strongly about. You can use your packaging and advertising to protest about issues – in the way that The Body Shop protested about animal rights, for example. You can also use it as a way to raise funds for charities that matter to you, and hopefully the product you are selling can be sourced in an ethical way.

For me, starting a business has completely changed my life. Not only has it brought me the financial freedom to live my life however I want, it has also taken me on wonderful adventures to over 50 countries – I’m extremely grateful that, unlike many of my friends, I don’t have to work every day in a job that I hate.

As well as being financially rewarding and a lot of fun, seeing my business grow from the first few jars I made in my grandmother’s kitchen to thousands of them adorning the shelves of supermarkets has been massively satisfying. It still puts a smile on my face when I walk into a massive supermarket store and see some jars of my jam there – especially in a foreign country!

Whatever reason you decide to start a business, the most amazing feeling is the one that comes from knowing that a whole adventure, a career and an impact on the world can all develop from just one simple idea written down on a piece of paper.

FOCUS

Our lives are so noisy. Noisier than they’ve ever been before. The average person checks Facebook more than 20 times a day. We take in information all day long from the TV, radio, newspapers, billboards, tweets, posts, YouTube videos, memes, FourSquare, text messages, phone calls, Skype, instant messenger, email and regular old-fashioned mail, and then somehow we even have some time left over for real-life conversations with the people we live with, the people we work with and the people we love.

We seem to have lost the ability to stop and think deeply about one thing at a time. We take in hundreds of ideas from all over the place and, instead of questioning each of them, we just take in the ones that fit and ignore those that don’t. We’re swamped with so much information that our brains are overloaded – we can barely think for ourselves any more.

And it doesn’t appear that anyone wants to live in the present moment either; the here and the now. Nobody picks up the phone and says, ‘Hey, what are you doing, fancy a coffee right now?’ That would seem weird in the always-busy society that we have created. Collectively, we suffer from the illusion of having a plan. It is assumed that we’re all busy right now. The moment is already taken. Today is already booked. Tomorrow is already booked too, so the here and now better just wait until next week.

We’re constantly scanning hundreds of different information outlets, waiting for something to happen, waiting for our lives to happen, waiting for some stroke of luck that will make all of our dreams come true.

In our work, we often tend to get to the end of the day not really knowing what we have achieved – have you ever experienced that sinking feeling when you leave the office after sitting at your computer for ten hours and ask yourself, ‘What the hell did I actually do today?’

We’ve completely lost the ability to focus all of our energy on doing one thing at a time. On doing a good job of one thing each day. Instead, we skim the surface of hundreds of ideas, hundreds of different tasks, not really doing the best we can at any of them and not fully achieving what we can with our lives.

What’s worse is that, by not committing ourselves to any one thing, we don’t really live, we just wait. People go to dinner parties and check their phone every five minutes. They go to parties and are always busy finding out what’s happening someplace else. If they could just live in the moment a bit more, enjoy what they’re doing at that exact second, life could be a lot more fulfilling and a lot more fun.

Something amazing happens when you start giving all of your attention to one thing at a time. Whether it’s the conversations you’re having, the ideas you are working on or the time you’re spending with the people you love, if you give each moment your undivided attention, you get the best out of every situation and the best out of yourself.

Generally, we have so many options as to what we can spend our attention on that we end up being completely scatter-brained. There are so many things we can do that generally we just do nothing. Making a choice and a commitment to focus on one thing is often a step too far for us. Infinite choice has a paralysing effect on our minds; it’s easier to decide to do nothing than to pick from an infinite number of choices.

People tend to get very little work done as a result of all this, and thus never truly fulfil themselves. I meet a lot of people who – paralysed by the limitless opportunities for work that our globalised, digitised world provides – have no idea what to do with their lives.

There used to be a time when most decisions were made for you – you’d work in the local mill or factory and live the same life as your parents and pretty well everyone else around you. But now, the choice of what to do with your life is completely up to you.

In this book, I want to show what can happen in just 48 hours of undivided attention. By focusing all of my energy on working on one simple idea for two days, it’s amazing how much ground can be covered. If we remove the constant interruptions of phone calls and Facebook updates from our lives, we can begin to work on tasks more deeply, enjoy our lives more, and have experiences with the people around us that are more meaningful.

The 48-Hour Start-Up is an experiment in focus. If you just devote all of your energy to a task that has a simple and clearly defined goal, you can achieve in days what you previously thought would take years. If, instead, you try starting a business in the usual way, with all of the distractions that our modern lives bring, it may well indeed take you years.

PIZZA PILGRIMS

How to make a living out of doing something that you love

Almost everyone loves pizzas, so to make a living out of selling them is probably a dream that many people have. But given that there are probably more pizzerias in the world than any other type of restaurant, it surely takes a bit of guts to set out to start another one in what is undoubtedly a fairly crowded market.

Undeterred, brothers James and Thom Elliot decided to go on their ‘pizza pilgrimage’ to Italy, buying a vintage Ape van and driving it back to London. They picked up recipes and inspiration for their restaurant along the way and now, several years later, find themselves running a small chain of pizzerias in London that has developed something of a cult following.

Their story certainly sounds romantic, and they’re definitely a couple of guys who are doing something that they love. But I know for sure that starting a business, especially a restaurant business, isn’t all romance and fun. When I caught up with them recently for our podcast show, they reflected on conversations they have had with some of their friends – friends who are maybe working in corporate jobs in their thirties and bored out of their minds.

‘Spending your twenties finding something that you love and are awesome at is the key.’ But they warn that you shouldn’t trick yourself into thinking that starting a business is going to be amazing every day and that you’re going to skip off to work each morning as though you’re in a Disney movie. What they can guarantee is that every day is going to be different. If you have a bad day, there’s nothing to say that the next day isn’t going to be amazing.

‘Don’t start a company because you want to have an easy life or because you think every day is going to be the best day of your life.’ Running your own business is an amazingly varied and totally at-your-control-type lifestyle, and that’s what these guys love about it.

‘When you work for a big company, it’s kind of like having emotional training wheels on – your best day is kinda great and your worst day is kinda bad. But when you work for yourself, your best day is kind of Shawshank Redemption rain-in-your-face amazing and the worst day is, well, really tough.’

On the topic of whether it helps to have a business partner with whom to share all of this emotional turmoil, they propose that it definitely does. ‘We’ve found that having a business partner has made the highs even higher and has meant that when we do have lows there’s someone there to get you through.’

You can listen to the full interview on the 48-Hour Start-Up podcast show at 48hourstartup.org.