Читать книгу John Muir - Frederick Turner - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

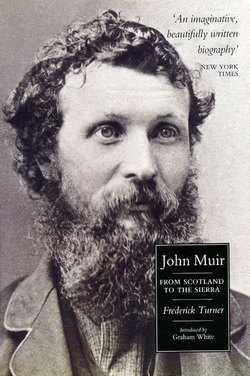

Frederick Turner’s biography of John Muir, published in America in 1985, is the first to appear in Scotland since Muir’s death in 1914, and may prove to be a watershed for environmental awareness in the land of his birth. It certainly represents a milestone for Scottish education and culture and will support the rediscovery and reclamation of Muir as a Scottish figure after a century of fame as an essentially American hero.

This biography tells the epic story of the pioneer conservationist, whose childhood encounters with wild nature on the beaches of Dunbar and among the oakwoods of the Lammermuir Hills, inspired his role in establishing the nature conservation system of the United States. Turner paints a vivid picture of Muir’s first eleven years in Dunbar, and of Victorian Scotland during the 1840s. During the research for the book he visited and explored East Lothian in considerable depth and discovered the actual deed of sale for the Muir home in Dunbar. He has read extremely widely on Scots history and culture, drawing on sources as disparate as the Border Ballads, Holinshed’s Chronicle of The Wallace and Johnson’s voyage to the Hebrides; he has studied the writings of Scott, Burns and Hogg, as well as Miller’s Victorian History of Dunbar. But this book is no mere academic biography; in Scotland Turner has walked the ground, climbed the castle ruins, read the newspapers of the time and visited the ancestral graves. From these many threads he has woven a rich and colourful tapestry which gives us a convincing impression of Muir’s Dunbar: the boat-thronged harbour, the life of the streets, the religious fervour and factions, the educational “school of hard knocks” and the precarious mortality which made death a common visitor. He has conveyed the magnitude of the adventure in which John Muir’s father, Daniel Muir, risked everything to board an emigrant ship in the freezing winds of February 1849, seeking religious freedom and a better life in America.

He has used the same research and literary skills to conjure the vast sweep of American history during that crowded and eventful century. He sets John Muir’s odyssey against the background of the greater westward migration and its consequences: the extinction of the passenger pigeon and the California Grizzly; the Indian wars that led via the battles of Little Bighorn and Wounded Knee to the virtual extermination of the indigenous Americans, along with the buffalo on which they depended; the California goldrush and the eclipse of the frontier wilderness by the rise of an industrial and economic giant. But Turner is more than just a brilliant historian; he is a gifted writer who creates images of enduring power, whether of Scotland, California or Alaska. In his appended “Notes on Sources”, Turner gives us a revealing insight into the biographer’s art and makes plain his own motives for undertaking the four-year project which resulted in this book; he was “disappointed by the flatness of the established portraits of Muir and their critical lack of historical and cultural perspective”. As a folklorist and professional historian, his primary aim was to present Muir in the historical and cultural context of his times, and he succeeds admirably. Indeed, the breadth of his research and the depth of scholarship are impressive.

Turner presents Muir’s life firmly in the context of the tides of history which swept millions of other Scots and Irish emigrants to the United States: the revolutionary unrest of Europe’s “Hungry Forties”, the Highland Clearances, the Irish Famine of 1847–48, the California Goldrush of 1849, the American Civil War and the great currents of religious and political thought in 19th-century America. Crucially, he illuminates the birth and emergence of the Conservation Ethic as a persistent theme in American society, largely as a result of Muir’s writings and campaigns.

Turner also uses a variety of innovatory techniques to bring his portrait of Muir to life. He wanted, he says, to go beyond the limitations of conventional biography and was not content to produce a mere hagiography of regurgitated letters, books and journals. Transcending these standard ingredients, Turner has re-enacted many of Muir’s experiences in order to reconstruct his “imagined perceptions”. During four years of research he has walked the cobbled streets of Dunbar on a rainy night, paddled in the white surf of Belhaven and explored the glens of the Lammermuir Hills. In Wisconsin he visited the Muir homesteads and dived among the lilies of Fountain Lake, to feel the rushes trail along his body in the sunlit water. In California he followed Muir’s trail to Yosemite’s high country to discover the sheep-camp and alpine meadows of My First Summer in the Sierra and tracked him along the Hiwassee river from Tennessee to North Carolina, while reading The Thousand Mile Walk. Envisioning these scenes through Muir’s imagined eyes, he has tried to reconstruct Muir’s feelings against the context of the literary and historical evidence, which he knows intimately. The result is a rich and engaging biography that brings the drama of Muir’s adventures to life against the backdrop of American history.

However, it should be remembered that Turner was addressing an American audience to whom John Muir is a household name, and saw little need in his prologue to chart the cardinal points of a life, which to millions of Americans, is as familiar as that of Henry David Thoreau or Martin Luther King. But in Scotland, and indeed the UK as a whole, Muir’s story has barely begun to be told and so Turner’s biography fills a crucial need.

In academic circles the contrast between the United Kingdom and the United States is dramatic: in America dozens of university and college environmental courses focus on the writings of Muir, as well as those of modern ecologists like Aldo Leopold, Wendell Berry or Rachel Carson. Similarly, many English departments offer courses on Literature and the Environment, which feature Thoreau, Emerson, Muir, Wordsworth and Blake, as well as contemporary writers like Gary Snyder. In the United Kingdom, with the exception of St Andrews’ Department of History of the Environment, or the research degrees in environmental values offered by Lancaster University’s Department of Philosophy, such courses are generally unheard of.

In our schools the knowledge gap is equally marked: for millions of American children John Muir serves as classroom hero and educational role-model. To them he is the very epitome of the mountain-man and muscular conservationist as depicted in more than a dozen children’s biographies. In Scotland and the UK until very recently Muir’s adventures and conservation ethos have not figured in the curriculum, although this situation is currently being addressed by the Education Departments of East Lothian and the City of Edinburgh.

For the general public in the USA, Muir is ensconced in the environmental pantheon alongside Thoreau, Emerson and Audubon; indeed for many, he has transcended mere historical fact to become a mythic archetype, casting his protective aegis across the continent as the ever-watchful guardian of Nature. In Scotland, he remains virtually unknown to the mass of people.

There is an enigma inherent in all of this; many historical figures are respected for their achievements, a few are even revered. But Muir is accorded something that goes beyond simple respect or historical stature, even eighty years after his death. Anyone who has visited the national parks of California, Wisconsin and other states will have encountered the reverence, and what can only be described as affection, with which John Muir is remembered. Almost every visitor centre recounts something of the tale of the Scots genius who fought to protect wilderness areas from the forester’s axe, the miner’s drill or the “hoofed locusts” of the sheep and cattle barons. Indeed, the maps and landscapes of America are indelibly stamped with the evidence of Muir’s success: Muir Woods, Muir Beach, Muir Glacier, Mount Muir, the John Muir Trail, and over two hundred other sites, testify to the enduring impact of his achievement.

Across the continent, over thirty schools and colleges proudly bear his name and, with Martin Luther King, he shares the rare distinction of a day in the calendar named for him. John Muir Day, every April 21st, is a focus for environmental celebrations throughout the United States, since it was resolved:

… by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America: that April 21, 1988, is designated as “John Muir Day”, and the President is authorized and requested to issue a proclamation calling upon the people of the United States to observe such day with appropriate ceremonies and activities.

But why is this Scot, largely unknown in his own country, ranked with Thoreau, Kennedy and King in the national hall of fame? And why is the name of this boy from Dunbar so deeply engraved in the hearts and minds of millions of Americans, and so liberally scattered across their maps? For some it is the sheer diversity of his talents and achievements that inspires admiration: emigrant, farm-boy, inventor, explorer, mountaineer, botanist, biologist, geologist, fruit-farmer, political lobbyist, presidential adviser, writer, poet, eco-philosopher and wilderness-sage. To others it is the epic nature of his journey from humble origins in Scotland, to eventual enthronement as the elder statesman of the American conservation movement; friend and adviser to presidents, he was lauded with honours by the greatest universities of his day.

Muir’s life affirms that most cherished myth of the American Dream: that hard work, self-help and self-belief inevitably lead to success in the land of equality and opportunity. And the difficult path which Muir travelled, with all of its mental, physical and spiritual hardships, still resonates deeply with millions of Americans whose ancestors fled economic and religious oppression in the Old World to build prosperous lives in the New. But for most people, it is as the founder of the conservation movement, the first person to call clearly for the conservation of wild places and wildlife, that John Muir is affectionately remembered.

Any traveller who ventures into the great wilderness of Yosemite National Park or any mountain or desert area in that vast country, is reminded that if John Muir had not fought to conserve all this unspoiled beauty, it might well have been destroyed long ago. Muir’s conservation battles were not easy ones, as Turner makes plain; they involved years of struggle against overwhelming odds before victory was assured. It should never be forgotten that Muir’s campaigns: to save the Big Trees, to extend Yosemite National Park, and to protect the High Sierra from annexation as a vast sheep ranch, were pitched against the flood-tide of rampant capitalism. This was the heyday of the “robber-barons”; the timber, mining and railroad magnates were busy stripping the forests, the gold seams and the mineral deposits of the west, building financial empires and accruing legendary fortunes.

Law and order was a tender new growth on the western frontier and choosing to oppose such rapacious interests could be unwise and even dangerous. Despite these threats, Muir confronted the richest and most powerful cartels in America at that time, along with their allies in Congress and the Senate, and he usually won.

His unassailable authority on conservation issues was grounded in hard-won mountain knowledge and many years of geographical and scientific exploration of the territory. Climbing the mountains alone, he studied the rocks and glaciers and mapped the distribution of the redwoods and sugar pines; he collected hundreds of plant species and traced the rivers to their sources in remote canyons. Gradually, the learned philosophers, geologists and botanists came to pay homage: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Sir Joseph Hooker, Louis Agassiz and Asa Gray of Harvard, all shared steep trails with Muir to benefit from his first-hand observations. Muir won the respect of many of the century’s greatest men by his remarkable synthesis of geology, geography, botany, and biology, which was unique at that time. In retrospect it is evident that Muir was a pioneer “ecologist”, almost before the word was coined in 1866.

Prior to the 1870s most Americans pictured their vast country as a boundless cornucopia, overflowing with inexhaustible reserves of land, timber, water, minerals, grazing and wildlife. But as the frontier closed, Muir witnessed the rapacious exploitation of this natural wealth by the timber, mining and cattle interests. He knew that such asset-stripping was unsustainable and should be opposed, but desperately tried to avoid any public or political role himself. Predictably, it was the wanton destruction of the giant sequoias which finally impelled him to act; in mapping the distribution of the Big Trees across the Sierra Nevada, he had been appalled to discover five sawmills reducing the sacred groves to mere lumber. The giant trees were often so large that they could not be felled by the axe or the saw and so were blasted with dynamite—a crude practice that blew valuable timber to smithereens.

Hoping to alert California’s law makers, Muir went public in a newspaper article on February 5th 1876, entitled: “God’s First Temples; How Shall We Preserve the Nation’s Forests?”. In this he explained the forests’ vital and complex role in relation to water and soil conservation as well as climate. Some historians point to this single essay as the moment when the American conservation movement was born; but for Muir it marked the reluctant acceptance of a career as an environmental campaigner, a role which he was never able to relinquish until his death thirty-six years later. But whether or not Muir wanted the national role as the champion of conservation, he had little choice; he was the right man, in the right place at the right time. Apart from his expert knowledge and experience, he had been gifted the passion, the oratory, and the literary talent which enabled him to cast the conservation issue in memorable words and to raise the debate in the national arena at a crucial moment in American history. His renowned charisma and storytelling ability enabled him to convince legislators, politicians and presidents that conservation of America’s wild places was as vital to the nation’s economic and ecological prosperity as it was to the people’s recreational and spiritual well-being. He was sustained in his noted campaigns by a singularly Scottish character founded upon endurance, self-reliance and the life-long practice of self-education. Apart from Thoreau, Emerson and Humboldt, his intellectual heroes included various Scots: the naturalist Alexander Wilson, the geologists James Hutton, Hugh Miller and Archibald Geekie and the writers: Robert Burns, James Hogg and Walter Scott.

Burns in particular gave Muir a profound respect for the democratic intellect and an utter disregard for matters of class, political power or social position: “the rank is but the guinea stamp, the man’s the gowd for a’ that” was for Muir a living testament.

Spiritually, Muir’s Christian faith proved a wellspring of inner strength, tempered by his scientific awe at the complexity of the universe. This was not the dark and sin-ridden Calvinism of his childhood in Scotland, but the illumined nature-gospel of Wordsworth, Thoreau and Emerson, buttressed with the scientific revelations of Lyell, Huxley and Darwin. Muir’s decades of field studies, his “readings in the great book of Nature”, left him with no doubt that a divine and beneficent presence permeated all creation.

His scientific studies revealed, again and again, that everything in Nature was subtly interconnected beyond our wildest imaginings; for Muir, “the hand that whirls the water in the pool” animated everything in the universe, from swirling nebulae to shimmering electrons. All things sang with beauty, purpose and meaning, from the epochal grind of mountain-sculpting glaciers to the evanescent “flower in the crannied wall”.

Muir’s cosmic vision was undoubtedly too radical to find a comfortable home in any church or school of materialist science. The very personification of Blake’s aphorism: “the cistern contains, the fountain overflows”, he needed neither the catechism of any conventional church nor lectures from the halls of academe.

The divine message was written clearly, for all to read: in flower, leaf and fossil; in snowflake and star. The divinity which shone through the entire Creation could not be contained in any metaphor, described in books or letters, limited by any religious creed or confined in any doctrinal bottle. And Muir never made the error of mistaking words and abstractions for the reality of the creation. He knew from bitter experience that “the word is not the thing, the map is not the territory”; books were “nothing but piles of stones, set up by the roadside to show where another mind has wandered” while words were mere “dry pebbles rattling in skeleton’s teeth” which could never convey the living, breathing beauty of the real world.

But whenever he turned from dry and dusty words to explore the mountains and read directly from the divine manuscript of Nature, he found the omnipresent evidence of pattern, order, connectedness, symmetry and universal law. And above all, pervading everything, he found the Grace of beauty, which he characterised as “the smile of God”.

President Teddy Roosevelt’s eulogy affirmed that Muir really did alter the consciousness of an entire nation, and even that of the President himself:

he was … what few nature-lovers are—a man able to influence contemporary thought and action on the subjects to which he had devoted his life. He was a great factor in influencing the thought of California and the thought of the entire country so as to secure the preservation of those great natural phenomena—wonderful canyons, giant trees, slopes of flower-spangled hillsides … our generation owes much to John Muir.

Robert Underwood Johnson, his editor and political ally in all his campaigns, wrote of him:

Muir’s public services were not merely scientific and literary. His countrymen owe him gratitude as the pioneer of our system of national parks. Before 1889 we had but one of any importance, The Yellowstone. Out of the fight which he led for the better care of Yosemite by the state government grew the demand for extension of the system. To this many persons and organisations contributed, but Muir’s writings and enthusiasm were the chief forces that inspired the movement. All the other torches were lighted from his … John Muir was not a “dreamer”, but a practical man, a faithful citizen, a scientific observer, a writer of enduring power, with vision, poetry, courage in a contest, a heart of gold and a spirit pure and fine …

Turner’s biography is deservedly regarded as the standard modern work, but since Muir biographies are something of a rarity in the United Kingdom, it is perhaps useful to place it in the context of other biographies.

Turner was the beneficiary of the monumental scholarship of the earliest Muir biographers, William Frederic Badè and Linnie Marsh Wolfe. The first attempt to deal with Muir’s epic life was that of Badè, his literary executor, who published The Life and Letters of John Muir in 1924. A theologian and university professor, Badè joined the Sierra Club in 1903 and became Muir’s protégé, supporting him in his campaigns and particularly in the battle against Hetch Hetchy valley being flooded as a municipal reservoir for San Francisco. After Muir’s death, Badè went on to become President of the Sierra Club, from 1918 to 1922. In setting out to compile The Life and Letters, he had hoped to collect perhaps a thousand letters from Muir’s correspondence; in the event he collected and transcribed over 2,000 of Muir’s own letters, as well as more than a thousand from other correspondents. This biography is now available as a new edition in the UK, since Terry Gifford included it in his second Muir omnibus, John Muir: His Life, Letters and Other Writings (Baton Wicks 1996).

Linnie Marsh Wolfe, the second Muir biographer, spent twenty-two years studying Muir’s letters, papers and journals, sixty of which she selected for John of the Mountains (1938). She went on to produce a full biography, Son of the Wilderness, The Life of John Muir (1945), for which she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1946. Frederick Turner generously acknowledges his debt to Badè and Wolfe who had, as he says, “sifted through the lateral, medial and terminal moraines” of Muir’s papers. In the lengthy work of sorting and cataloguing these, they created order out of chaos and pieced together the chronology which has served as a rosetta stone for all subsequent researchers; if Turner has seen further and deeper into Muir’s character, it is because he has stood on the shoulders of giants.

The Rediscovery of Muir in Scotland

The publication of Turner’s biography in Scotland will undoubtedly introduce a new generation of readers, students and academics to the story of Muir and his significance for the world conservation movement, which is only now becoming apparent, even to scholars in the USA.

It is a sobering thought that even Japan was ahead of Scotland in acknowledging the stature of her emigrant son. Kato Noriyushi published a book entitled A Saint in the Forest: The Father of Nature Protection ( Tokyo 1995), and other Japanese books on Muir are also available. Several years ago, Daisy Hawryluk, the owner of John Muir House in Dunbar, opened her door to discover a Japanese professor kneeling in prayer on a square of white silk, placed reverentially on the pavement outside the birthplace of the “Great Soul”. He had travelled halfway around the planet to pay homage at the site, where for him, the seeds of modern environmental awareness were sown. The Japanese attribution of “great soul” or its Indian equivalent “mahatma”, does not sit easily with us in our increasingly secular and materialist society, but Muir does inspire such profound respect in other cultures.

The event which began the process of Muir’s rediscovery in Scotland occurred in 1967 when Bill and Maimie Kimes, the eminent bibliographers of Muir, left California to undertake an environmental pilgrimage to Dunbar. They wrote to the town’s Provost asking if some local historian could guide them around the castle, the harbour, Muir’s birthplace and the beaches where he had first encountered wild nature in the 1840s. On receipt of their letter, the lady Provost began an urgent search for background material on Muir, of whom she knew little. To her embarrassment, neither Dunbar library nor the county library in Haddington had a single copy of any book by John Muir, or about him. Finally, after considerable effort, some volumes were borrowed from Plymouth on the south coast of England, five hundred miles from Dunbar.

Following their return home, Bill and Maimie Kimes wrote a letter of thanks, gently suggesting that Dunbar might acknowledge its most famous son by placing a plaque on the house in which he was born. The Provost replied thanking them for their suggestion and reported that a plaque had been agreed upon by the town council; it was eventually installed in 1969 with the inscription: “Birthplace of John Muir, American Naturalist, 1838–1914”, which reflects the perception of Muir in Scotland at that time.

In view of the fact that for over seventy years Muir regarded himself as Scottish, spoke with a marked Scots accent and became an American citizen only late in life, the plaque might more accurately describe Muir as a “Scottish-American Naturalist”. Indeed, as the “Father of the American National Parks”, and arguably a seminal figure in the birth of the world-wide nature conservation movement, Muir was rather more than just a “naturalist”. It would be gratifying if, in time for the Millennium, a new plaque with a more edifying inscription were to be installed at Muir’s birthplace.

The 600th anniversary of the founding of the Royal Burgh of Dunbar followed in 1970 and, perhaps inspired by the Kimes’s visit, a modest exhibition of Muir books and photographs was arranged by the Planning Department. The exhibition organiser was Frank Tindall, who served from the 1950s until 1975 as County Planning Officer for East Lothian; but until the Kimes’s visit of 1967 he had heard virtually nothing of John Muir. In 1974 Tindall began negotiations with the Earl of Haddington for leasing part of the Tyninghame estate that is now called John Muir Country Park; it was officially opened in 1976. The park’s 1660 acres of wild coastline include the golden sweep of Belhaven Bay as well as the saltmarsh and mudflats of the Tyne and Biel estuaries, dotted with curlew, shelduck, oyster-catchers and eiders.

This wild nature reserve, stretching eight miles from the ruins of Dunbar castle to the wild Tyninghame coastline in the west, overlooks teeming colonies of gannets, puffins, razorbills and guillemots on the Bass Rock and the Isle of May; for hundreds of thousands of subsequent visitors the park has been an invitation to familiarity with the Muir story.

Accompanied by his wife and son, Tindall travelled to California in 1977 to track down the details of the Muir legend. They hiked in Yosemite National Park and visited Muir Woods to the north of the Golden Gate. On Muir’s birthday they were fêted at a Sierra Club barbecue in the grounds of Muir’s Martinez home and were invited to stay at the Kimes’s “Rocking K Ranch” in Mariposa; friendship blossomed from this hospitality.

On their return home they were convinced that Scots should be made aware of the world stature which their kinsman had achieved. But ironically, they discovered that Muir’s birthplace was now threatened with re-development as a fish and chip shop! Fortunately East Lothian Council had no problem agreeing with Daisy Hawryluk, the owner of the house, that the upper floor should be converted into the Muir birthplace museum. The restoration of the house went ahead and in 1980 John Muir House was finally opened to the public; it now attracts visitors from all over the world.

Tindall was appalled to discover that in 1978 the National Library of Scotland did not hold a single copy of any of Muir’s books, nor any of the biographies and literary analyses produced since 1924. However, the National Library willingly agreed to host the first Scottish exhibition of Muir’s life in 1979, and for many people this was the turning-point in raising national awareness of Muir in Scotland. Thereafter the National Library began a comprehensive collection of Muir books and manuscripts which includes a microfilm archive of the collected John Muir Papers. However, for the general public, Muir’s books remained virtually unobtainable in the UK.

In the light of this, Tindall approached Canongate Publishing in Edinburgh with the object of creating the first Scottish editions of Muir’s works. This led to the publication of Muir’s unfinished autobiography, The Story of My Boyhood and Youth in 1987, followed a year later by My First Summer in the Sierra, both issued as Canongate Classics with the support of the Scottish Arts Council. These were re-issued in 1996 as part of a five-volume omnibus entitled John Muir, The Wilderness Journeys, which included three other books: The Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf, Travels in Alaska and Stickeen.

The gradual repatriation of Muir’s ideas and ethos to Scotland has not just been literary. In 1983 the John Muir Trust was established in Scotland, to purchase and conserve wild land for future generations. To date the Trust has bought four areas of wild land in the Highlands and Islands, totalling 34,000 acres: Li and Coire Dhorrcail in Knoydart, Torrin on the Isle of Skye, Sandwood Bay in Sutherland, Strathaird and Bla Bheinn in the Skye Cuillin. None of these areas is “wilderness” or “wild” in the American sense; they all have crofting communities and people have farmed here for hundreds of years, possibly for thousands. But whatever the label, these wild landscapes, the haunt of the golden eagle, red deer and otter, are among the most beautiful and unspoiled in Britain.

The John Muir Trust aims to demonstrate exemplary management of these areas, sharing responsibility with local communities for the sustainable use of the landscape, wildlife and natural resources. It aims to foster a wider knowledge of Muir’s life and work among the Trust members as well as the general public.

The John Muir Award

In 1994 the present writer proposed the creation of a prestigious award for environmental endeavour, to be called the John Muir Award. This was intended to address the disturbing fact that less than 15,000 young people in Scotland were actively involved in environmental conservation, from a target population of 1.3 million. The scheme, which was nationally launched in February 1997 by Scottish Environment Minister Lord Lindsay, is non-competitive, open to all and is offered through partnerships with existing educational, youth and environmental organisations. It aims to offer people a warm welcome to involvement with the environmental movement, with the emphasis on first-hand experience, action, fun and adventure. It is hoped that by the Millennium, the John Muir Award will have welcomed many thousands of young people and adults into a lifelong commitment to conservation, and that such involvement should be the norm, rather than the exception. It is also intended that the Award should honour the memory of John Muir and his achievements and encourage Scottish children and adults to emulate the ethos and example of their famous kinsman.

Frederick Turner’s superb biography is published in Scotland at a crucial point in the UK’s environmental history: the native forests are long vanished along with the wolf, lynx, bear, beaver, polecat and many other extinct species; the nation’s fish stocks are poised on the brink of ecological disaster with successive crashes in the population of herring, mackerel, salmon and now cod; the intensification of farming under the EEC’s Common Agricultural Policy has pushed once-common farmland birds, like the thrush and the skylark, towards comparative rarity throughout the UK and the only economic model which any government or local authority dares to contemplate is growth, growth and yet more growth.

Consequently, the reassessment and reclamation of Muir as a Scottish writer and environmental thinker is a vital process which anyone who cares about Scotland’s environment, its education system and culture should actively support.

In a country whose ecology has been impoverished by the loss of over 99 per cent of its native woodlands, together with many animal and plant species, the repatriation of the world’s greatest advocate of forest conservation is of crucial importance.

In an historic fishing nation, whose marine resources have been pillaged to the extent that cod may soon be declared an endangered species, bringing home the prophet who campaigned for the sustainable use of natural resources as long ago as 1876 is a timely event.

And for a culture where less than a third of one per cent of the children are actively involved in conservation, the reclamation of John Muir as a Scottish writer, conservation hero and educational role-model could mark a turning-point in the historical estrangement of the mass of people from their own landscape and wildlife.

Graham White. Dunbar, April 1997