Читать книгу John Muir - Frederick Turner - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue: Peru Again

Through the American summer of 1848 Congress thrashed about in the moral wilderness created by the territorial acquisitions from President Polk’s Mexican War. The issue the new lands raised into stark view was slavery—its limits and its future—and over the factional forensics in Washington there now loomed the thunderhead of sectional conflict.

During these months another state came into the steadily expanding union: Wisconsin, a free state, was added to balance the newly acquired slave states of Florida and Texas. The acquisition required the swindling of the tribes native to the new state, but this was so minor a matter, judged in the scale of national controversy, that it was generally ignored.

Eighteen forty-eight was also an election year, and in summer’s heat conventions were held at Baltimore, Rochester, Philadelphia, and Buffalo. Hysterical and self-congratulatory as these gatherings were, the platforms adopted by the Barnburners, Free-Soilers, Liberty Leaguers, and others prophesied the collapse of a national house increasingly divided against itself.

On August 19, the New York Herald ran a lengthy item on that most intriguing of the Union’s new acquisitions, California. Buried some 2,000 words and thirteen paragraphs into this early specimen of California boosterism was mention of the gold discovered the previous winter at Sutter’s Mill on the American River. This rich vein, the writer said, was only three feet below a surface of soft rock and sand and was so extensive it was safe to predict a “Peruvian harvest of the precious metals as soon as a sufficiency of miners &c can be obtained.”

The article with its almost perversely obscure reference to the California strike did not engender a gold rush, nor did it by itself even confirm the first whispered rumors to reach the East. It did, however, add by its language a significant bit to the gathering force of those rumors. The adjectival characterization of the strike as “Peruvian” was a mother lode itself, calling up peculiarly American desires and dreams of riches that waited somewhere beyond the hand-to-mouth realities of the known world: Argonauts, gold of Ophir, Cortés in Mexico, Dalfinger and Aguirre hunting the Gilded Man through South American jungles, the Pizarros looting Peru, where it was said they had captured a golden cable so heavy that 600 natives could barely lift it… .

For more than a century now, emigrating whites filling up the imponderable spaces of this New World had been forced by the persistent nonappearance of further caches of the fabled riches to reformulate their hopes on a more modest scale. By the middle of the nineteenth century the luck of the conquistadores seemed truly a matter of the past. But the old dream lived on in America and in the Western mind, and at the end of the summer of 1848 it was brought to quick life again. America, accidentally discovered on the way to Eastern riches, once more blazed out in the popular imagination as the land of the quick, lustrous strike.

As summer turned into fall, rumor continued to feed hope. On September 20, the Baltimore Sun ran a sensational story about the strike, and a few days thereafter the New York Journal of Commerce wrote that Californians were running over the country and picking gold out of it “just as 1000 hogs, let loose in the forest, would root up ground nuts.” Now there were stirrings all along the eastern seaboard, in the South, and up and down the Mississippi Valley. By November, samples of California gold had found circuitous ways east, people held the palpable stuff in their palms, and the first ships put out for California.

At the end of the month, President Polk had in hand an official firsthand account of the strike, and when he delivered the last of his annual messages to Congress on December 5 he incorporated the glad news in an otherwise sobering discussion of the perils of the large, unretired national debt. Few if any of his listeners cared about the debt. In newspaper accounts of the message, the lead paragraphs dealt with the confirmation of the gold strike. The gold rush was on.

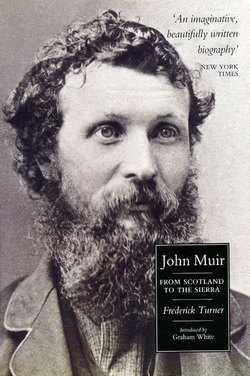

Had Sam Brannan, who announced the gold strike at Sutter’s Mill, bellowed his news in the heart of London or in Edinburgh’s Princes Street, the effect on the Old World could not have been more electrifying than the news contained in Polk’s message. The word “gold” immediately leapt free of its context and flashed along the port cities of Europe, up the watercourses, and into the columns of newspapers and journals already crammed with alluring information on emigration. In the tiny North Sea fishing village of Dunbar, Scotland, even the dour master of the grammar school showed some excitement and allowed his pupils to exhibit some of their own. To ten-year-old Johnnie Muir this latest American news seemed almost too exciting to bear. In their reading book he and his classmates had already been awed by accounts of the vast American forests that contained such marvels as the sugar maple and by descriptions of the wonderful wildlife these forests harbored. Johnnie Muir had been especially taken with the descriptions of the fish hawk and the bald eagle by the Scots naturalist Alexander Wilson, who like so many of his countrymen had gone to the New World after the American Revolutionary War. The boy read Wilson’s words over and over again until he knew them by heart. And now to be told there was also gold in this fabulous country! Visions of hawks, eagles, red Indians, huge trees oozing sweets, and gold glittering in the mighty gloom of the wilderness filled Johnnie Muir’s head.

Such dreams may be the special and perishable blessings of childhood, yet there is good evidence that in varying degrees of vividness they were shared in these years by the adults of Dunbar and a thousand other towns and villages of the Old World and for reasons that had as much to do with European realities as American promises. At midcentury, the Old World seemed faded and chaotic, the New World bright with limitless prospect. The latest news merely made the contrast the more obvious and the impulse for emigration the more compelling.

The three decades since the Congress of Vienna had redrawn the map of Europe had seen an accelerating pace of social and economic disruption amounting to a cultural revolution. Every aspect of life from family relations to international trade was profoundly affected. What is now called the First Industrial Revolution was then a bewildering phenomenon of so many facets that not even the most farsighted social philosopher or statesman could begin to comprehend it all or predict the direction and consequences of the changes taking place. Only the great poets of the Old World could then correctly intuit some of the consequences of all this on the hearts and minds of humankind, and few were listening to them.

Well into the nineteenth century the old certainties of the medieval world, apparently long vanished in the smoke and blood of war and the political rearrangements of the intervening centuries, had survived as emotional preferences and habits of living for millions in the rural areas. Now even these were being utterly obliterated in ways more final than could have been accomplished by the blasts of cannons and the changes of flags. The very landscape that had nurtured the old ways of thought and life was fast vanishing into the pits of industry, swallowed up by the expanding industrial centers. And the old assumptions of a fixed abode, of place, of hierarchical obligations, and of home-centered labor were being roughly uprooted without effective alternatives in prospect. Village life was being deliberately sabotaged by those who owned the lands surrounding the villages and who now saw new ways to make those lands yield greater profit.

Agriculture, once the basic mode of life, was becoming increasingly consolidated and at the same time was becoming distinctly subordinate to the cities with their factories, ports, commerce. Even in the years when harvests were good, agriculturalists suffered because of lowered selling prices. And when crops were poor—as they often were in what were known in Scotland as the “Hungry Forties”—there was hunger and indeed famine, and not just in the newly spawned cities. Such had been the case in 1845, so it was again in Ireland in 1847 and 1848, and in the latter year the condition spread from Ireland to infect much of the Old World and to leave a scar on the European consciousness: such sights, such scenes of unparalleled, irremediable suffering could not easily be forgotten or understood as the bottom curve of some huge cycle. They must instead portend the end of something.

The year 1848 confirmed the general fear of crisis, for not only was there the agricultural failure and famine; there was also the attendant economic crisis. Eighteen forty-five and 1846 had seen wild speculation in wheat and railroads; then the huge wheat purchases had been followed by a bad harvest. In England business houses failed in droves, thirty-three of them in London alone in 1848.

Above all this hovered the specter of revolution on the Continent. In Paris the king had been forced to abdicate, leaving the Tuileries to the vengeance of a mob. There had been upheavals in the German and Italian states and in Hungary. In Vienna, even the grand political puppeteer Metternich had been forced to flee to England before the threat of mob violence.

Assessing the situation, the Edinburgh Review in its July-October 1848 number took a very Burkean view, admitting the real possibility of political collapse everywhere, a contagion emanating from France’s “huge chronic ulcer,” the “foul and purulent” contents of which were now disgorged upon all nations. Plainly, in order to deal with the mobs of unemployed and dispossessed, extraordinary remedies might be temporarily required, “among the rest, greater facilities to Emigration—a subject which has lately, and justly, claimed so large a share of public attention.”

With the exception of the Irish, the Scots were perhaps the most susceptible to encouragements to emigration, and a man like Daniel Muir, Johnnie’s father, had grown up hearing talk of American opportunities while all about him he was discovering evidence of his homeland’s historic poverty and overpopulation. Daniel Muir was born in 1804, precisely the period in which a more general recognition had come to the Scots people of just how far their country lagged behind the community of modernizing nations and of how far it was likely to stay behind. Scotland’s problems, exaggerated by the convulsions of the Industrial Revolution, were in fact endemic.

As early as the eighteenth century the Scots financial adventurer John Law (he of the Mississippi Company Bubble) succinctly identified the country’s major problem: numbers of people, he observed, “the greatest riches of other nations, are a burden to us.” The country was simply too poor to support a large population. Law’s personal solution was to try his fortunes abroad as did ever-increasing numbers of his countrymen as the century wore on and conditions darkened. The years 1763–75 saw almost 25,000 Scots leave for Nova Scotia, Canada, and America, a figure that would later look paltry but in that time was of sufficient magnitude to become a major public issue.

From the Highlands, where barren gray rocks dropped precipitously into the waters of lochs and range behind range of mountains and hills bore only the tough furze and heather, the people came down to try their luck in the Lowlands, and then, finding the prospects there equally grim, went to America, about which the news was so unfailingly good. There were stories of the American soil’s great, almost magical fecundity, of the inexhaustible resources, of space for a free life. And those who had seen the Glasgow tobacco dealers grow fabulously wealthy on a product of the American earth, sporting their scarlet cloaks and gold-knobbed canes, could not doubt the factual basis of these rumors. Journals like the Scots Magazine, which featured a special section on “British North America,” and the Chambers’s Information for the People and Edinburgh Journal catered to the rising interest in emigration to America. Crèvecoeur’s Letters from an American Farmer enjoyed a sustained popularity after its first publication in 1782. In it Crèvecoeur had written extensively of the Scots immigrants descending from the “high, sterile, bleak lands of Scotland, where everything is barren and cold,” lands that “appear to be calculated only for great sheep pastures.” He retailed the representative history of one Andrew, an honest Hebridean, who arrived in America pale, emaciated, and virtually without resources yet who in the course of four years became “independent and easy.”

They were still coming down from the high country and out from the Lowlands forty years after Crèvecoeur wrote, for the conditions that sent the emigrants to the New World were only intensifying. The Highland clearances that had begun in the 1780s had by the 1820s increased in scope and ruthlessness as thousands of Highlanders were thrown off the land to make room for sheep. So too with the agriculturalists of the Lowlands, where consolidation and modernization were squeezing out the small farmer. Even the once-prosperous weavers of Glasgow, Paisley, Renfrew, and Lanarkshire now felt the pinch as thousands willing to work for almost any wage crowded into the industry. After 1815 the weavers became the most prominent occupational group in the emigration movement, and in Lanarkshire alone they had organized thirty-two emigration societies.

Growing up in that Lanarkshire district, Daniel Muir would surely have noticed all this, would have heard the talk of the New World and of the plans of the emigration societies. Daniel Muir’s flight from the backcountry to Glasgow around 1825 was part of the larger pattern and was the first step in his own eventual emigration.

Muir had been born in Manchester, England, where his soldier father was then stationed in the British army. Shortly after birth Daniel had been orphaned by the deaths of both parents, and the baby with his eleven-year-old sister Mary was taken back to the father’s home region of Lanarkshire and raised there by relatives.

In nearby Glasgow, despite some feeble child-labor statutes, small children regularly worked thirteen-hour days, and in the cotton mills of Lanarkshire similar brutalizing routines were in force. So it is not difficult to imagine that life for the orphan Muir children on the farm near Crawfordjohn was anything but idyllic. There on the high moors, surrounded by steep mountains that suffered but a few bleak villages and some lead mines, Daniel Muir “lived the life of a farm servant,” as his son John was later to write in an obituary notice. He continued in this when he moved to the neighboring sheep farm of Hamilton Blakley after his sister Mary had become Blakley’s wife.

Given the numbing routine of such a life and the absence of parental affection, it is a little surprising that Daniel Muir should ever have displayed much joy in life or any interest in its non-utilitarian dimensions. Yet at some point in his calcified maturity he confessed to his son John that on the Crawfordjohn sheep farm he had taken pleasure in carving little images out of whatever materials were at hand. He had also made himself a fiddle and had learned to scrape across its catgut strings the tunes of hymns and ballads. The native Lowlander is said to be an outwardly dour type who conceals the warm romanticism that bubbled out in Burns and Sir Walter Scott, and if circumstances deny him any effective outlet for the romanticism and demonstrativeness within, the result can be a grim, crabbed character. So it proved with Daniel Muir, and whatever his talents for life, for art and music, they were crushed out of him in the monotonous grind of agricultural servitude. He gave up the carving, though the fiddling and singing lingered on for a few years as a pathetic, vestigial remnant of the suppressed side to his character.

The most significant event in Daniel Muir’s Lanarkshire apprenticeship to life was his conversion to a brand of evangelical Presbyterianism. Indeed, this was to prove the most significant event of his entire life and, it might be argued, of the lives of those who were to be his family and who would be forced to bear the burdens of his spiritual convictions. At some point in adolescence the Word in the dress of flaming, hellfired rhetoric was brought to the lonely farmhand, and he found in the love of Jesus something of what his earthly circumstances had denied him.

The specifics of the conversion experience are unknown, whether it came as the culmination of broodings while carrying buckets in muddy boots; or while in moments in his metic’s cot before exhausted sleep; or whether some bellows-lunged marathon evangelizer reached the boy on a single, indelible Sunday. Nor is it known which brand of evangelical preaching among the many was decisive. The Scots have always been a divided people with a historical predilection for disputation and “hiving off” into a welter of small and smaller camps of opinion. This is particularly obvious in religious matters, where there exists a long, reddened record of religious warfare. The years of armed strife in Jesus’ name were over by Daniel Muir’s time, but the schisms and splinterings continued, and in the period 1806–20 there existed seven different Presbyterian churches plus other smaller evangelical sects like the Glassites or Sandemanians.

What probably attracted Daniel Muir most in the message he heard was the addition of emotionalism to the ascetic piety of Calvinism and the displacement therein of the elitist doctrines of election and predestination. The most obvious source for this development was the influence of John Wesley, who in the course of his career made twenty-two proselytizing trips to Scotland; he gained few actual converts to Methodism through these, but his influence on the tenor of Scots religious practice was enormous. In a larger sense, this evangelical element was another of the myriad consequences of the Industrial Revolution, which had created new conditions for which the old modes and doctrines of worship now seemed inadequate. The poor, the dispossessed, the laboring masses, those like young Daniel Muir, needed some sort of fire in their lives, and evangelical religion with its odor of brimstone and its passionate promises of true equality in the hereafter gave it to them. As John Nelson, the English stonemason, told Wesley of Christ’s poor, “No other preaching will do … but the fine old sort that comes like a thunderclap upon the conscience.” Daniel Muir’s conscience was struck in that way, and it remained so throughout his life. In his subsequent position as tyrant-head of his household and in his later career as a backwoods Wisconsin preacher and wandering evangelist, he would strive with a grim earnestness to direct God’s thunderclap upon the consciences of his listeners.

In the meantime, he discovered that as one of Christ’s poor this was a hard world to live in, and that some places might be harder than others. So in his early twenties he became part of that shifting, often confused mass of his countrymen seeking more hopeful prospects. But leaving the farm was one thing, a gamble Daniel Muir and thousands of rural people willingly took; accommodating oneself to city life was another. What Daniel Muir encountered in the Glasgow of the 1820s was enough to disabuse him forever of the idea that the city offered anything more than another version of the miseries of the backcountry. At the same time, having experienced the limitations of Scots life in, both places, he may have recognized in the Glasgow episode the potential virtues of that even bigger gamble, emigration.

For Glasgow as Muir encountered it was fearfully overcrowded, having grown without plan more than 100 percent since the turn of the century. Sanitary conditions were hopelessly inadequate, and the old dread diseases like smallpox, typhus, and cholera had reappeared. Gangs of unemployed laborers, displaced rural folk—like Muir fleeing the farms or else thrown off them—aimlessly roamed the streets. Beggars clogged every corner. Hundreds of public houses ministered in their way to the despairing, and to get drunk was said to be “the short way out of Glasgow.”

Another way out and one more congenial to Daniel Muir was to accept military service, as had his father before him. He took it, though it can have done little to ameliorate his view of life’s harsh, regimented necessities. In the course of this tour he found himself on a mission as a recruiting officer to the fishing village of Dunbar.

How long Sergeant Muir stayed on this particular mission is now unknown, but it was long enough to meet, court, and marry a Dunbar woman and to persuade her to buy his release from service with some of her inheritance money. Muir took over the grain and feed store that was another portion of her legacy, and he was apparently in the process of turning it into a going concern when his wife died, leaving him in sole possession.

Given the conditions of the time and Daniel Muir’s own situation, it would seem that this would have been the right, natural time for him to emigrate: he was alone and childless, a comparative stranger in Dunbar, and for the first time he possessed enough capital to make a good start in the New World. He must have seriously considered it, but Daniel Muir stayed on, and it may be that he did so because he had become involved with another woman. Early in 1833 he married Anne Gilrye.

Anne was a tall, serious-faced young woman who lived with her parents diagonally across the high street from where Muir had reestablished his business in a narrow three-story building faced with the Upper Old Red Sandstone so pervasive in the East Lothian region. The parents, David and Margaret Gilrye, both came from old and proud Highlander families and had done well in Dunbar, where David had sold meat until his retirement. They considered their daughter somewhat above the obscure young widower across the way who each Sunday could be seen turning to the right out of his store and marching with military resolution down the sloping street to the kirk on the hill. In that same kirkyard lay six of the Gilrye children, victims of various respiratory diseases, and it would have been natural for the parents to have been protective of Anne, eager to guard her against a bad marriage.

In order to marry her, Daniel Muir had to overcome the strong objections of the father, but the root of these was not social; it was religious. David Gilrye was a Church of Scotland man, satisfied with the state and practice of Presbyterianism within the established body and probably defensive toward enthusiasts like Daniel Muir who thought establishment worshipers not so much satisfied as complacent with dry formalisms. If David Gilrye intuited that such a man, all but consumed in his zeal and arrogantly sure that others of differing shades of opinion were no Christians, would make a hard husband and father, he was right. Anne Gilrye’s life with Muir was hard indeed, and her comforts mainly those achieved through her connections with her children and in her private life, which she took care to shield from her husband. The marriage was to end many years later in separation.

Muir family tradition has it that Anne Gilrye was of a “poetical” nature in her maiden years, a euphemism generally indicating that thin indulgence sometimes granted young women to moon over ineffables and to write harmless verse in the period before life and its realities—husband, home, children—should begin. If she did once write poetry, none of it survives, but in her later letters to her son John there are suggestions of these conjectured youthful inclinations, and in the lines the work-worn farm woman wrote there is some evidence of that romanticism her son was able fully to express and that she could vicariously express through him.

But the woman was no silent cipher in the Muir household. When in 1834 the children began to come, Anne Muir did her best to protect them from the uncompromising rigidity of the father’s beliefs and behavior. Had she been any less successful, Daniel Muir’s tyranny and bigotry, unchecked and unleavened, must have produced corresponding deformities in the children. As it was, all were apparently sufficiently well adjusted—though all bore the marks of such a father—and for this the mother must be given considerable credit. In the pictureless, spartan house that Daniel Muir insisted upon, Anne Muir taught her children how to endure, and how to express and enjoy themselves when the father was elsewhere. They all had to wear the harness of Daniel Muir’s beliefs and character; she showed them how to wear it in some comfort.