Читать книгу My Heart Sutra - Frederik L. Schodt - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

RELIGION AND ME

ОглавлениеI grew up overseas, and because my parents were members of the Foreign Service, airplane travel was always part of my life. It has remained so, but I’ve never particularly enjoyed flying. As a tiny boy, in the days of propeller planes, when there was far more noise, turbulence, and problems with cabin pressurization, on take-offs and landings I would sometimes clutch a tiny New Testament—the “pocket” sort often handed out for free to children at Sunday School in the mid-1950s—and try to recite the Lord’s Prayer in hopes that the plane would not crash. That Testament is still on a shelf, with my nickname “Fred” scrawled in the shaky, primitive pencil letters of a very small boy.

I was raised a Christian, but I’ve drifted from that world. My somewhat religious father went to church when he could, accompanied by my dutiful mother who, except for enjoying choir singing, was usually happy to stay away and perhaps an atheist at heart. My brother and I were baptized in a Presbyterian church in Washington, D.C., and attended a Lutheran church in Norway and occasionally a Methodist church in Australia. Mainly, I remember the pent-up energy that resulted from being imprisoned in narrow pews and four walls for an hour, and the knock-down fights with my brother that often later ensued. Sometimes, in Sunday schools, we were given religious paraphernalia. As a child, on my bedroom wall, I had a wooden plaque, rounded and spoked in the shape of a ship’s wheel, showing a profoundly hippy-looking Jesus calmly navigating storms (presumably of life). It always gave me solace. I also had a plastic cross that glowed in the dark; in retrospect, given the era, it may have been somewhat radioactive, much like early watch dials, but under the covers at night when feeling insecure it, too, seemed to calm me. On my deathbed I’ll probably see images of Jesus, long ago burned into my brain cells, flicker past me.

Buddha in the Redwoods.

When I was thirteen, in Australia, my father gave me the choice of continuing to attend church or taking my dog—an unrepentant Welsh corgi—to dog-training school; of course, I chose the latter. When I was seventeen, at an international high school in Tokyo, Japan, my parents were given another diplomatic assignment, but I chose to remain in Japan to graduate. I lived in a tiny dormitory mainly for missionary children (which I was not), and on Sunday we were usually required to attend some sort of Christian service. I often attended local Quaker meetings, which were almost Zen-like in their minimalism and probably the closest modern Christianity gets to Buddhism. I was a bit out of sync with at least one of my dorm mates, who viewed me as nearly beyond redemption, later writing in my senior yearbook, “I would challenge you to read the New Testament…. Some people may call me a religious fanatic, but if I have tasted honey and you have not, I am not going to shut up.”

In the fall of 1967 something happened that affected me. I say “something,” because memory is tricky. In my mind, a famous American evangelist was speaking at my school’s small gym, telling us that if we didn’t take Jesus Christ as our savior we would go to Hell instead of Heaven. Given that Japan has a vanishingly small Christian population of only around 1% and given that I had grown up in a highly multicultural world, this message, rather than bold and courageous, seemed terribly misguided and wrong. All those Japanese—whose culture I admired—were they condemned to suffer in hell for eternity, and me with them? I even remember the evangelist as the late, legendary Billy Graham, who visited Tokyo that year on what he called a “Crusade,” speaking in front of an adoring crowd of thousands in Tokyo’s Budōkan stadium. Yet there is no record in the school archives of him ever visiting the school. Some of my more religious dorm mates did indeed go downtown to hear him, but no one seems to remember him coming out to our school. Is my memory assembled from their reports? Is it a phantom, or conflated with some other event or other speaker at the time? Real or imagined, to me it has always been real, and troubling. In a sense, something turned a switch in my mind.

After that, my contact with official Christianity more or less ended. I still have deep appreciation for its emphasis on love and compassion and forgiveness. I believe the world would be a shallow place without any of the Abrahamic or monotheistic religions. But I am not comfortable with the intolerance and cruelty to which the “mono” in “monotheism” can so easily lead. Nor am I comfortable with the always anthropocentric—or human-centric—structure of most religions.

I now consider myself religious only in a vague way—made up of something like a religious and philosophical soup, I might say, starting with a vague base of Christianity to which has been added animism, nature worship, transcendentalism, the Gaia theory, Buddhism, a dash of Taoism, and other poorly understood systems. Neither atheist, nor agnostic, I’m probably pantheistic, for I’m willing to believe in multiple “higher authorities,” but I have no formal affiliation with any specific organized religion. Nor do I have the discipline to completely immerse myself in one, for to me most seem based on a few profound insights, wrapped in layers of complexity and dogma, infused with the usual human arrogance and delusion. While Buddhism has always appealed to me on an intellectual level, I must confess that I am not even a practicing Buddhist, or even a meditator. In short, I’m a typically modern, lazy, only occasionally spiritual being. And after watching too many people drift into Christian fundamentalism, or later into various Asian religious cults, or even into political extremes, I’ve developed an allergy to any sort of blind faith. When I look at animals and trees and the sky I will never be convinced that any human knows all the answers.

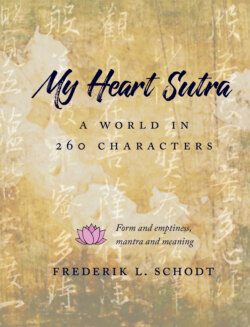

Having said all that, I’m not immune to a certain envy of those who have what might be called “faith.” And the closest I come to this religious “faith” is a fascination with and fetish for the Heart Sutra, or what is known in Sanskrit as the Prajñāpāramitā Hṛdaya Sūtra, sometimes translated as “Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra.” Other religions may have prayers or scriptures somehow similar in usage or philosophy. That, I do not know. This book is about the sutra that I found, about my relationship to it, and my explorations into its usage, both ancient and modern.