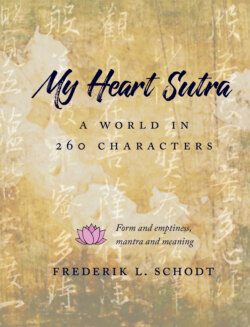

Читать книгу My Heart Sutra - Frederik L. Schodt - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A RESOLUTION

ОглавлениеWhen the captain of my plane first made his announcement, I felt in control of my anxiety. But something seemed odd. Why should we turn back to Oakland because we didn’t have enough thrust in an engine if we were half-way to Burbank? Wouldn’t it make more sense to go on to Burbank? My doubts amplified, and then we circled in the sky once, twice—in my memory three times.

On the third time, I felt a true surge of anxiety. It was September 12, after all, only a day after the anniversary of the notorious terrorist attack on New York by hijacked planes back in 2001. And while most people might not have made the same association, for me, odd as it may seem, the circling in the sky made me think of Japan Airlines Flight 123, one of the worst disasters in airline history. On August 12, 1985, the four-engine 747 jumbo had been on a regularly scheduled flight from Tokyo to Osaka. A bulkhead and subsequent hydraulic failure caused the pilots to lose directional control, and after weaving and circling crazily in the sky for an appalling thirty minutes the plane smashed into the mountains outside of Tokyo. Of the 524 passengers, all died except 4, who were grievously injured. Many had been returning to their family homes to celebrate Obon, the All-Souls Festival of Japan, when the souls of ancestors are said to return to their homeland.1

The accident created a wound in the Japanese national psyche, and in trying to absorb it people would later write books, create mournful songs, movies, and even a manga, or comic book, about it. In what to me was always one of the most disturbing ideas at the time, passengers had had over thirty minutes to contemplate their doom, and several even wrote out farewell notes that were later found. Among the notables on the plane was Sakamoto Kyū, the singer who had popularized one of my favorite songs, “Ue wo muite” (“I Look Up as I Walk”), an extraordinarily mournful ballad. When exported to the United States in 1963 it had been given the improbable name of “Sukiyaki” (presumably because that was one of the few Japanese words Americans then knew) and become the first and only Japanese song to top the U.S. pop charts.

So, while staring out the window of my far more modern plane, while others seemed to take it all in stride, I had my white-knuckle moments, with too much time for contemplation added. In such situations, I’ve always struggled to put things into perspective, no matter how hard it might be to do so. We’re all going to die at some point, right, so why worry? After all, one of the tricks I have used as a child (and even as an adult) on boarding airplanes has been to assume that I’m already dead. It helps, but it’s not enough. Under extreme strain, the mind hopes for some sort of prayer, some sort of incantation, something simply to cling to psychologically. When actually dying on the battlefield, soldiers are often said to call for their mothers; but I wasn’t at that stage yet, since the plane hadn’t crashed, or even really lost control.

What I needed was just to steel myself. As a child, I might have recited the Lord’s Prayer with absolutely no comprehension of what I was saying, but I no longer remembered it. At that moment on September 12, 2016, had I had the presence of mind, I would have recited the entire Heart Sutra. It’s one of the shortest of all Buddhist sutras, and it fit perfectly with my view of the world at that moment. The only problem was that, while holding out myself as something of a devotee of the Heart Sutra, out of sheer intellectual lethargy I had never memorized the entire thing.

What I did know very well was the mantra at the end of the sutra. The part that goes, Gaté gaté pāragaté pārasaṃgaté bodhi svāhā (gaté is pronounced more like “ghateh”). It’s only six words long in transcribed Sanskrit and only 18 ideograms in Chinese and Japanese out of a total of 260 (or 262, if you are from Japan). It has a nice melodic ring to it, and for decades now it has always been my secret weapon, my personal incantation for salvation against pain and fear and mental turmoil.

After circling three times, the captain turned the plane north and, with presumably limited thrust in one engine, we limped back to Oakland Airport. We landed safely, and Southwest Airlines, to their credit, with extraordinary speed and efficiency transferred all the passengers—who seemed to take it all in stride—to another, mechanically uncompromised plane. We took off once more on the hour-long flight to Burbank, and to my surprise I even made it in time for my interpreting assignment in Los Angeles. The company also gave all its inconvenienced passengers a $150 voucher for future flights. I hadn’t expected much, and merely felt relieved, so I was entirely happy. Much later, however, the incident would cause me to spend many hours exploring the dusty corners of my brain, trying to understand how I first became enamored of the Heart Sutra mantra, and how I had even learned of it in the first place. This made me want to know more. Eventually, I realized that contemplating the Heart Sutra, memorizing it, chanting it, copying it, even writing about it, could be my practice, my fragile toehold in what most people might think of as the world of faith.