Читать книгу TransNamib: Dimensions of a Desert - Gabi Christa - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe lonely North-West

The diversity of the Namib Desert starts in the Northern Cape. The southernmost fringes of the desert extend from Angola to here where they meet, almost tenderly, in the Karoo. The border of North-West Province is indicated by a big signpost. Huge granite boulders, created by woolsack erosion, grow higher and higher the further we travel. The fields literally are in the pink; red soil showing between the low shrubs and grass stubs. Granite is an intrusive rock composed of quartz, feldspar and mica. The most common form of granite erosion in arid regions is the so-called woolsack erosion. The rock erodes along the criss-crossing fissures through granular exfoliation, producing boulders with the shape of a wool or cotton sack. Big and heavy as they may be, their rounded shapes add an expression of tenderness and harmony to the landscape.

The farm buildings are always quite a distance from the road. Telephone and power lines branch off to the houses, ensuring their inhabitants connect to the outside world. Lacking trees, birds take to these high poles to build their nests. They provide more security to the young brood than the single low quiver trees (Aloe dichotoma pillansii), growing on the hills.

Climbing a quiver tree is not a step too far for a snake. These peculiar trees belong to the aloe family. Simon van der Stel, the first governor of the Cape, called this tree “kokerboom”, since the locals used its hollowed branches as quivers (known in Afrikaans as koker) for their arrows. Once I observed a one metre-long snake invading the nest of a colony of Sociable Weaver birds, thoroughly pillaging it. Since then, I’ve always looked above, before settling under a tree.

The lonely Northern Cape is the largest of the nine South African provinces, with an area of 361.800 km². Only 1.8% of the population, 2.3 inhabitants per km², live here. One of the reasons may be the very scarce rains in this region. The prevailing savannah landscape in the east is taken over by bush and grass steppes towards the west. These merge into the so-called Karoo. In the language of the locals this signified the “land of thirst”. More prosaically, Karoo stands for sediment rocks, which developed 150 to 250 million years ago. The largest part of the region is covered by the barren semi-desert Karoo, where you can expect just 120 to 400 mm of rain a year, or none at all. Only adapted flora and fauna can cope with this harsh climate. Nevertheless, there is a wonderful spell hidden in this barren landscape. Different species of dry grasses survive until the next rains and then turn it into a garden in full bloom. Each year, during the wildflower bloom in the months of August and September, visitors flock in great numbers to the Northern Cape. Along the river beds, which occasionally hold water, different bush-size tamarisks grow, alongside acacias and succulents. The barren areas are increasing because of agricultural grazing and recurrent dry seasons, which hinder the regeneration of the landscape. Forests have been cut down for firewood and timber. The consequence for the fragile semi-desert Karoo has been erosion scars that are beyond repair. Almost imperceptibly the Karoo tapers into the fringes of the Namib Desert, which stretches in a 120 kilometre-wide strip northwest up to the coast. While in the Karoo sheep chew on dry grass tussocks, in the Namib there is no life outside the dry river beds. Some plants and animals who manage to extract vital humidity from nocturnal dew or the coastal fog provide astonishing exceptions and are the real specialists in coping with the harsh living conditions in the desert.

Garies acquired its name from the local Khoisan, and means “creeping grass”, its population is about 1.500. It was founded back in 1845. Not much is going on here, although Garies is the agricultural centre of the Namaqualand district. A huge billboard at the entrance to the village touts it as the Heart of Namaqua.

Again, the weather worsens. The wind is blowing coldly and the clouds close off the sky, but this does not spoil the beauty of the landscape. Big stones, made round by erosion, lie scattered across the ground. The surrounding area is enchanting, as described by Veronica, and we understand her enthusiasm for her home area. Between Garies and the next place, Kamieskroon, a subtle green carpet has grown after the recent rains. This is unusual for this time of the year and just a few days of radiant sunlight will burn this cheeky green in no time.

Springbok, the capital of Namaqualand, at 1.000 metres altitude, is named after the small quick antelope which used to be frequent here. This town is not only perfect as a base for visitors who come to see the wild flowers blooming, it is also the pivotal point for the neighbouring copper and diamond mines. The former governor of the Cape, Simon van der Stel, significantly supported these mining activities.

Counting a population of 15.000 and lots of shops, life in this modern town seems to defend itself against the rural lethargy. In the main street, in front of the large shops, there is a great clutter of makeshift stalls, offering a large diversity of products. I snake my way to the shops past belts, baskets, suits, bras in bright colours and plastic toys. The alluring fragrance of barbeque makes my mouth water and I look around to locate it. A woman with a baby strapped to her back catches my glance, points at my worn-out slip-ons and with a smile shows me a pair of elegant high-heeled strappy sandals. Their artificial leather has faded and grown hard already in the sun; the high heels wouldn’t be suitable for our journey, so no bargain is made. As in all of the larger settlements in this region people from the different ethnic groups in the vicinity congregate here. People are hopefully pursuing their dreams and trying to find out where and how to make them come true.

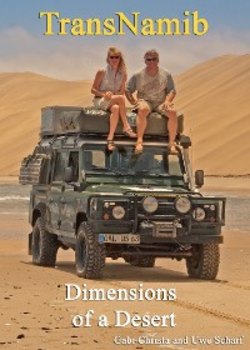

This is our question as well, since we won’t make it now to the Orange River. So we put up camp behind a hill, between some granite boulders, not far from Springbok. During this leg of the trip we are travelling in two vehicles. Our group comprises: Heiko and his girlfriend, Anke, who will, however, only join us in Walvis Bay, Uwe and myself. An ice-cold wind blows over the rocks and we sit at the bonfire wrapped in thick layers. Woolsack erosion is working on this rock as well – chipped-off pellets of granite are lying in the red sand as if they have been left behind.

Camp close to Steinkopf