Читать книгу Dr. Leff - Gabriel Constans - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

BOMBS AWAY

ОглавлениеFred Branfman emerged from the jungles of Laos carrying a heavy load. He wasn’t weighed down with ammunition, guns or rations. The international volunteer, who had been in and out of Laos for over three years, was burdened with something far greater than goods or a heavy backpack.

What he carried were photographs, drawings, documents and stories of the Laotian people and the devastation that had been inflicted upon them by United States bombs - bombs that officially didn’t exist; bombs that burned flesh, chopped off limbs, took the lives of mothers, children, elders and babies; bombs that destroyed homes, crops and entire villages; bombs that were intended for the communist Pathet Lao.

It was 1969 and the war in Viet Nam was full bore, though much of the fighting had been diverted from ground troops to killing by air. From 1968 through 1974, the Indochinese populations of Viet Nam, Cambodia and Laos had more ordinance (including cluster, fragmentation, Napalm, and 500-pound bombs) dropped on their lands and people than did the Koreans, Europeans and Japanese during the entirety of the Korean War and World War II. The Pentagon estimated that they were dropping about six million pounds of bombs per day. Historically a gentle land of farmers, most Laotians had no idea why America was trying to destroy them.

Few Americans had heard of the destruction taking place on The Plain of Jars (known for clay pots) and its 50,000 inhabitants, let alone Laos; and the U.S. government was intent on keeping it that way. U.S. reporters were not allowed on bombing runs into Laos and were restricted from speaking to military brass. Everything surrounding the raids was “classified”; but not all the people who witnessed or knew of the carnage could be silenced.

Fred Branfman carried pictures of people on the ground, the victims of high altitude, impersonal air strikes authorized by US Ambassador Godley and frequently directed by the CIA. He had close-ups of unexploded bombs bearing the symbol of the U.S; bombs dropped by American pilots who had never met a Laotian, let alone knew one. But Fred knew them personally; he had been to their homes, talked to the elders and shared meals with families and communities. Fred was in bed, not with the military, but with the stories of the Laotian people. He was embedded with scenes and images he would rather not hold. He was embedded with unbearable atrocities that had been committed by his fellow Americans. He was determined that the truth of these events not be buried with the Laotian people or minimized by U.S. propaganda that denied civilians were ever targeted.

The words he held included those of Nang Pha Sii’s mother-in-law. “In August, 1969, the jets bombed. Nang Pha Sii, my daughter-in-law, was in a trench. A bomb landed nearby, killing her father and wounding her mother and two other villagers. She was killed, shielding her year-old baby with her body.”

MeOu’s son-in-law said, “Me Ou was 59 when she died on February 20, 1969. It was a cold day and she decided to leave the trench about 3 p.m. to get some clothing for herself and the children. The jets bombed while she was in the house. She was burned alive.”

A refugee from the Plain of Jars had explained, “There wasn’t a night when we thought we’d live until morning . . . never a morning we thought we’d survive until night. Did our children cry? Oh, yes, and we did also. I just stayed in my cave. I didn’t see the sunlight for two years. What did I think about? Oh, I used to repeat, “please don’t let the planes come, please don’t let the planes come, please don’t let the planes come . . .”

Another refugee had shown him his daughter. “This is my daughter, Khamphong. She’s three years old. I was fishing in a stream with all seven of my children on February 28, 1969. Suddenly jets came and dropped anti-personnel bombs all around. Six of my seven children were hit. See, you can still feel many pellets in Khamphong’s legs and back. There were no soldiers nearby.”

Some Laotian Peace Corps friends of Fred’s told him about a young captain in the Air Force who was going to Washington to testify about the bombing of Laos to the Fulbright Foreign Relations Committee; the most powerful committee in the senate, chaired by Senator William Fulbright. They’d said this captain was a physician at the Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base in Northeast Thailand, just over the Laotian border. The base was a hub for the US and CIA aircraft that were bombing the very people he held so dear. This officer had put out the word, through his civilian friends and employee’s of Air America (a front for the CIA), that he was looking for informational ammo about the situation in Laos.

How this captain had been so blatant and survived being thrown out of the Air Force was beyond Fred’s comprehension. He was just glad there was somebody sane enough to listen; someone who might be able to help stop the madness.

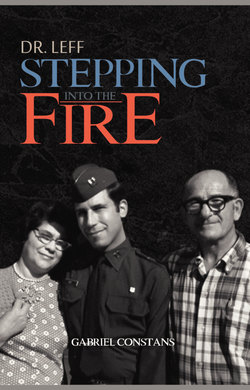

In late fall of 1969, Fred Branfman met Cpt. Arnie Leff, MD, USAF, at The Bungalow, a counter-culture way station for off-duty military and civilians traveling throughout Southeast Asia. He entrusted all his papers, files, interviews and photographs about the bombing of Laos to Dr. Leff, a passionate Jewish-American kid from Brooklyn who had the guts, chutzpah or naiveté, to stand up to the US military and political regime and say, “This is wrong. This isn’t the America I believe in.”