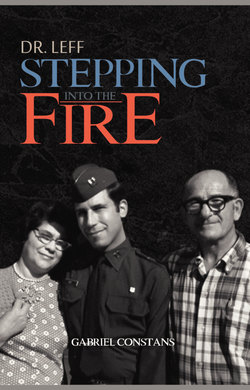

Читать книгу Dr. Leff - Gabriel Constans - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

NURSED BY PATRIOTS

ОглавлениеYou couldn’t have had a more unlikely whistle blower than Captain Leff.

Arnold (Arnie) Leff was born in Women’s Hospital in Brooklyn, New York on December 2 1941, but his family soon moved to the Bronx in order to find an apartment. It was the beginning of the US involvement in World War II and apartments were scarce. After the war, his uncle, aunt and their children, lived in a Quonset hut in Brooklyn, due to the shortage, even though the huts had originally been designed for temporary use.

Arnie’s father, who was two old for the war and had already served in World War I, commuted an hour each day to work at the gas station he owned in the Bedford section of Brooklyn. Though the hours at work and on the road took their toll, Arnie’s family felt lucky to have an apartment anywhere in the city, let alone a two bedroom with one room for his parents and the other for their only child. Arnie’s mother and father attempted to create a sibling for their son, but all attempts ended in miscarriage.

His mother, Pearl Charlotte Lynn, was born in Jersey City, New Jersey on April 30, 1917 and was a full-fledged “Jersey Girl” like her mother before her. His mother’s father, on the other hand, was born in Russia and had an entirely different cultural experience and understanding of America.

Pearl was Arnie’s primary source of emotional nourishment as a child, since his father worked from 10 in the morning until 10 at night most days of the week. He remembers his mother doing volunteer work and helping as a secretary at his elementary school (Bronx PSA 85), but her primary focus was on being in charge at home. She cooked, cleaned, did laundry, attended school events and got him up and going in the morning to make sure he got to class on time.

By the time Dr. Leff’s father married his New Jersey sweetheart, who was fourteen years his junior, he had already been through one world war and a multitude of character building conflicts on his home turf.

David Lefkovisc was born in Hungary on August 30, 1903 and moved with his brothers and sisters, at age five, when his parents brought them to the United States. They were processed, with thousands of other Europeans, at Ellis Island. His Hungarian name was spelled Lefkovisc, but when they came through immigration the authorities changed it to Lefkowitz. By the mid 1940’s it was changed once again, this time shortened to Leff. Because of anti-Semitism and a backlash against immigrants, David Lefkowitz decided to follow his brother’s example and change the family name in order to get a job. His brother was a plumber, but couldn’t get a job with the Plumber’s Union because he was Jewish and had a “foreign” sounding name. Due to this blind discrimination David Lefkowitz once again changed the family name, this time to Leff.

David Leff had a combative, abused childhood on the Eastside of New York and left home as soon as possible. He used his brother’s social security number to join the Army when he was only sixteen. The year was 1919, but instead of winding up in the madness of “the war to end all wars” in Europe, he was sent to Panama as a surveyor. Somewhere in Panama, there is a mountain with a little plaque in his honor called Mount Lefkowitz.

Not long after his return from military service during World War I, the Great Depression came rolling across America, throwing bowls of dust in everyone’s eyes. Housing, economic growth and the belief in a better tomorrow were trampled under foot until President Franklin D. Roosevelt brought out the New Deal and created the Civilian Conservation Core (CCC). He lifted up America and gave its people a renewed sense of hope and purpose. David Leff received a job working in the CCC camps during the 1930’s and was proud, in later years, to show his family the letter he received “from FDR himself” lauding his work in the CCC. If David Leff’s family had not already been die-hard Democrats before the depression, the New Deal made them life-long believers.

When the US became engaged in the Second World War, all of David Leff’s male cousins joined the military and went off to fight “the good war”, the “moral war”. There was no doubt that it was the “right” thing to do, but David couldn’t go. He was already a veteran from the first war and was too old for duty. But he wasn’t too old to fight the battles that needed fighting in the middle of New York.

In the early forties David worked his way up from gas station attendant to own several stations himself. It was common practice at the time to pay the cops for protection, which he did for several years. The same police were also paid by companies to break up rallies and demonstrations of workers who were demanding 40 hour work weeks, health benefits, protection against injury or simply the right to be heard. Not surprisingly, in retrospect, David Leff became president of the Oil Workers Union. He was a labor organizer. Being part of a union in the early forties, let alone one of its leaders, was no walk through fairy land. Protestors and pickets were routinely beaten up and thrown in jail and Mr. Leff had his share of cuts, bruises and unpleasant stays in New York’s “finest” cells and jails. It wasn’t uncommon for union leaders to suddenly disappear altogether.

David didn’t reserve all his fighting for labor disputes and police. His son remembers stories from his uncles and aunts about numerous arguments and fights his father got involved in or started, including one at his own wedding. Someone at the wedding party said something David didn’t like and he started punching away. He didn’t need to be drunk to put up a fight, it was in his blood. It was how he survived as a boy and believed as a man. You fought for your honor, your self respect and your family.

By the early forties, when Pearl Charlotte Leff gave birth to her son in the borough of Brooklyn, her husband, his family and the rest of America were at war. They believed in a strong defense, in liberty and truth. They saw Dwight Eisenhower and General MacArthur as heroes. In spite of his dealings with corporate America and company thugs, David Leff still believed in justice and the American way of life.

Arnie recalls the times he went with his Uncle Sydney, after the war, to the American Legion and how they all attended the Memorial Day parades and watched proudly as it coursed through the Bronx Grand Concourse. It was an important and valued yearly event. The US had won the war and saved the world. Patriotism was the norm, the expected. Nobody questioned the military, it was respected and revered.

The Leff family liked to party. Whether it was for a birthday, a religious holiday, a picnic, going to the beach, camping or having the family over for dinner; relatives were always close at hand. They drank, laughed, kidded and danced. In addition to riding a horse at the age of two, Arnie remembers celebration upon celebration, with the women of the family preparing food and treats and arranging the festivities and the men driving to the store for booze or telling private jokes just out of earshot of youngsters and “ladies”. Parties were about the only time he ever saw his dad or saw his father loosen up. For a generation where many still believed in kids being “seen and not heard”, the Leffs were the exception. They took pride in their children and encouraged them to act out and be part of the celebrations.

In 1950, when he was nine years old, Arnie already had a good sense of who he was. On a page of his fifth grade notebook it states that he had a crush on Marjorie Thurston and played the scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz. It went on to say that his favorite books were the Hardy Boys and his desired profession was “to be a doctor”.

Two years later, at junior high school, a page in his yearbook provides the following insight into his future. His favorite motto is “Crime does not pay!” His favorite book is Tarzan and best song Kiss of Fire sung by Georgia Gibbs. His hero at the time was Crimebuster. Mark Twain topped his list for authors and he believed Princeton was the best college. For profession . . . “Doctor”. This was the same year (1952) when he played accordion at the Music Centre Conservatory Town Hall in New York on June 11th. If you put all these elements together, you have an eleven year old who sees himself as a Mark Twain look-alike accordion playing doctor, belting out Kiss of Fire at his graduation from Princeton!

As Arnie became a teenager it would have made sense for him to attend high school at the Bronx High School of Science, which was only six blocks from his home and rated one of the top high schools in the city. For various reasons, including his image of that school as one for “geeks”, with which he did not want to be identified (even though some at the time may have categorized his intellectual and social abilities as falling well within the geek Norma culture), he chose not to attend and applied to the Brooklyn Technical High School, which was an all-boys student body that focused exclusively on science and engineering. Over 10,000 young men applied to be freshman from the New York City area, but Arnold Leff was one of only 1500 that were accepted for the following year. He got what he wanted, but it was no piece of cake.

Brooklyn Technical High School was about order, discipline and study. Arnie was giving engineering a close look and made that his major. From 8:30 in the morning until 4:00 in the afternoon, 6,000 boys rotated from math, to shop, to industrial science and chemistry. Science and math took up the majority of the lectures and labs and were grounded in preparing students for college. Arnie loved it. He excelled at his studies and was praised for his work. He understood how guys thought and acted and enjoyed the macho, no nonsense atmosphere.

He joined the school’s service squad, which were like elite hall monitors. They were given badges for their duties and were generally well respected. It was no small task to keep 6,000 boys moving from class to class through long hot or cold days in New York City and make sure they all arrived and left school safely. The service squad kept the boys in line in the morning, as they waited to enter school and get on the freight elevators that would take a hundred at a time to various floors. The line stretched all the way out to Fort Green Place, the street in front of the school and down the sidewalk. And there were the lunch periods – three in a row with 2,000 students per period. To say Arnie and the service squad had their hands full, on top of their own studies and responsibilities, is an understatement.

When he joined the service squad he had only just turned fifteen. It was his first taste of authority and in spite of the immense challenges it provided or because of it, he felt like he had found his niche, his place, a reason to be proud of who he was and what he did. It wasn’t long until he was promoted to lieutenant and had his first command. Even though it was as a civilian and as part of the service squad in school, it gave him the experience he wanted and a peek into the possibilities for his future.

His time at Brooklyn Technical High School and as a member of the school service squad were exemplary, except for a little strain of rebellion that eventually broke through the cracks of his all-business demeanor. It was the food that did him in and provided the only reprimand he received in four years of service.

After two years of eating the mush the cafeteria staff called food, Arnie decided he’d had enough and took it upon himself to organize the only act of civil disobedience he has ever committed then or now. As a sign of protest, he convinced over 2,000 students to all bring pennies to pay for their lunch on a specific day. The cafeteria staff was outraged as they frantically took payment from thousands of students who waited in line jingling their pockets full of pennies. Arnie and the students told the staff they’d start paying with dollars when the meals improved. When it was learned that Arnie Leff was the ring leader of these actions, he was reprimanded. It had only been symbolic, but the administration claimed it was petty and irresponsible. As Mr. Leff was in a position of “authority” he “should have known better”. A most interesting coincidence however, was that the cafeteria food became more varied and better tasting, at least for a few months.

One of the drawbacks to a school that took kids from all over the city, was that they all went home to their respective area of town after school and didn’t have many opportunities to play, study and hang out together. Boys from Queens went home to Queens, guys from the Bronx returned to their familiar streets and kids from Manhattan returned to their island. The advantages included learning how to get along with people from different backgrounds and providing a sense of unity, understanding and common purpose among borough’s that historically mistrusted or disliked people that weren’t from their neighborhood.

One of the boys Arnie befriended in his sophomore year was a kid named Joe Petti, from Queens. It was during lunch one rare sunny fall afternoon that Joe told Arnie about the Civil Air Patrol. He said that his big brother Jerry and he had both joined and it was “really cool”. He invited Arnie to join him for one of their upcoming meetings at Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn. Arnie agreed and stepped into his next home away from home. It would be his first official membership in the US military and his first social encounters with the opposite sex, as girls could also join the Civil Air Patrol and attended the same meetings.

Dr. Leff recalls his first meeting of the Civil Air Patrol. “I saw shiny Air Force uniforms and as is the case with most fourteen year olds, I was enthralled. I joined the cadet corps of that volunteer civilian auxiliary of the United States Air Force. Little was I to know that seven years later I would still be an active member; nor did I realize that this organization, dedicated to leadership and aviation training for teenagers and the saving of lives through air search and rescue, would have such profound effects upon me. In my seven years as an active member, I learned leadership and compassion; service and dedication. My pay: great satisfaction.”

The Civil Air Patrol was founded at the beginning of World War II to protect the coasts of the US. They provided countless hours of surveillance on the watch-out for German or Japanese submarines. Most of their planes were small Piper Cubs, not military fighting machines that were used overseas. After the war the Air Patrol continued as a voluntary search and research organization. The United States Congress then made it an official auxiliary of the US Air Force. By joining the Air Patrol in 1955, Arnie Leff essentially joined the Air force as a young volunteer. It had a cadet core that was trained in military protocol and expectations and some of the cadets were women.

Joe Petti, his brother Jerry and Arnie were having a blast. They attended meetings and trainings in full uniform and “had crushes on all the women”. Arnie got so involved in Air Patrol activities that for the first time in his life his grades dropped at school. They didn’t drop enough to cause any trouble, but he knew it was significant.

On the weekends they would go to Floyd Naval Air Station and learn how to fly old rusted aircraft that made Arnie’s mother, “pull out her hair”. They learned how to navigate, use radio for communication and how to fly. In the summertime they attended two weeks at a Civil Air Patrol Military Camp, which were held at Air Force bases in the area. The camps provided training, discipline, skills, ribbons and ranks. Occasionally, they were called up to go search for a plane or boat that had crashed or disappeared.

Arnie got a student pilots license “that I never used” and obtained the rank of captain. A rank of captain for a high school student was impressive. The Civil Air Patrol ranks cadets the same as the Air Force, which starts at airman first class and goes up the latter to airman second class, third class, staff sergeant, master sergeant, warrant officer, second lieutenant, first lieutenant, captain, major, lieutenant colonel, full colonel and general. In the Air Corp the highest ranking was major.

As he became a senior Air Patrol cadet Captain Leff began teaching the leadership courses and military practice to younger cadets. He especially enjoined attending the Mirror Air Show (sponsored by the New York Daily Mirror) as a senior cadet, where they would recruit new cadets and talk to young people about the Air Force. He was proud of the organization, his part promoting it and in what his uniform signified. He felt that they were doing good and “making a difference”.

By the time Captain Leff was a senior at high school, as well as a senior cadet, he was nominated by the Brooklyn Civil Air Patrol to participate in their national Cadet Exchange program. This program would take a few selected cadets from the United States and pay all their expenses to visit another country. That country would do the same and send its cadets to the US. Only one or two cadets from the entire state of New York would be chosen from all those nominated and Arnie Leff was one. “When I was selected I had no idea where we were going. For all I knew it could have been Antarctica or Timbuktu”. It turned out to be Switzerland.

A few months later, a young group of seven cadets assembled at Mitchell Air Force Base in New York to begin their journey for a months stay as guests of the Swiss government. They flew from Mitchell to Bolling Air Base and then took another flight to Goose Bay, Labrador, in northern Canada. They spent the night at Goose Bay and were able to witness the beauty of the Northern Lights. They couldn’t fly directly to Europe at the time, as their DC6 didn’t have enough fuel capacity to fly from New York straight to Switzerland. Now it would take about five to six hours. In 1959 it took days.

They were treated like royalty, met government officials, spoke to the press, stayed in the best hotels and were chauffeured around in army limousines. It didn’t hurt that Arnie had taken two years of French in high school and new a little bit of German. One of the highlights for Captain Leff was meeting the legendary Swiss mountain rescue man Herman Geiger and being flown, with the other cadets, to the top of a glacier in the Swiss Alps. “We flew 10,000 feet into the Alps, landed on a pure white glacier and all got out. Geiger and the other pilots dig in the snow and find bottles of wine they had put there earlier in the day and make a toast. Can you imagine, standing on the top of a glacier in the middle of Switzerland and being toasted by Herman Geiger. It was unbelievable - the crisp air, the brilliant sun and the snow-covered peaks that surrounded us and looked like they were rushing up to kiss the blue sky.”

It wasn’t long after his return from Switzerland that Arnie Leff decided to go to the University of Cincinnati and Hebrew Union College, a Reform Rabbinical Seminary, to become a Rabbi. He had been thinking about it for some time and had been attending an orthodox school down the street from his high school during his senior year and having long, in depth conversations with its rabbi Sidney Applebaum. Ironically, it was his time in the Civil Air Patrol that ultimately convinced him of the need to be involved in a profession that helped others and looked at the “big picture” in life.

His family had never been particularly religious, in fact, his father was an atheist. His mother had kept a kosher kitchen for a few years, but his father had said it was too much of a hassle and insisted that she quit the practice. His mother was adamant that their son attend Chader “at least”, while he was in elementary school. Chader is a Hebrew word for a Jewish religious school.

Arnie attended the orthodox Jewish center each afternoon following public school. He says that he wasn’t impressed and got “irritated” at the teachers, who insisted that he not talk with his neighborhood friends, who were Irish and Italian Catholics, about Christmas. It seemed to him that the Jewish religious teachers at that school were just as bigoted towards Christians as some Christians are towards Jews. He also felt rebuffed when he would ask questions that would not be answered or were dismissed altogether. He stopped going once he was in high school and had his Bar Mitzvah (right of passage to community and with God) in a conservative temple. To round out his young Jewish experience and quest for understanding, he attended several orthodox services, including the ones with Rabbi Applebaum in high school. He liked the chants and traditions of orthodoxy better than the songs and secularism of the reform movement, but also felt that a lot of their etiquette (including wearing the Yarmulke – small round covering for men’s heads and the status of women) were outdated and hypocritical.

“It’s quite ironic,” Arnie says, “that it was Rabbi Applebaum who wrote my recommendation for Hebrew Union College. To have an orthodox Rabbi support someone who wanted to attend the dreaded reform college was a radical thing to do in 1958. Rabbi Applebaum would kid me and say I was his juvenile delinquent going to reform school.”

It was at a wedding in upstate New York that a friend of Arnie’s had introduced him to a reform Rabbi who had gone to Hebrew Union. They talked for quite some time and Arnie pumped him for information about his experiences there. He liked what he heard and continued corresponding in the following months. Hebrew Union College had an undergraduate program that continued into a graduate program. The Reform Rabbinate was also the first to allow women to attend. Students lived at the seminary in Cincinnati and went half time to the University of Cincinnati to take college courses. Then they would attend rabbinical courses at Hebrew Union College for the other half.

“I wanted to leave New York and this sounded like the ticket.” Arnie recalls. “It felt like it was a spiritual birth or rebirth of something I’d been searching for. It also involved a bit of getting back at my father, with whom I had a guarded relationship, at best, by pursuing something he didn’t believe in. Even though it didn’t end up giving me all I thought it would, it was a great experience and helped me sort out my priorities. I still have wonderful friends who are Rabbis all across the country.”

Arnie stayed with the rabbinical program for a year and a half until he was turned on to an exciting new world; a world that helped people with practical everyday issues, a world that gave him the tools to not just talk about life and death and “what we are here for”, but to nourish and care for the bodies that give us the opportunity to even ask such philosophical questions.