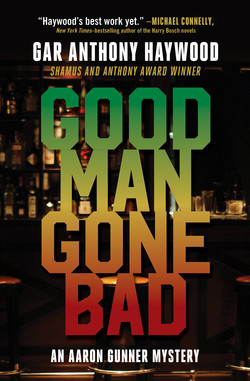

Читать книгу Good Man Gone Bad - Gar Anthony Haywood - Страница 10

Оглавление1

“AND THAT WAS ALL HE SAID?”

“Yes.”

“He didn’t—”

“No. He didn’t say anything more than what I’ve just told you, for what? The fourth time now?”

“We apologize, Mr. Gunner,” the detective said. His name was Luckman, Jeff, and his low-key manner was almost soothing enough to compensate for the freezing cold of the little police interrogation room and the rickety, uneven legs on Gunner’s chair. “But we’re just trying to understand what happened here.”

“You’ve already told me what happened. My cousin killed his wife and tried to kill his daughter, then turned the gun on himself.”

Even now, many hours after he’d first heard the news, it sounded more like a joke than a matter of fact. Del and his wife, Noelle, were dead, and their twenty-two-year-old daughter Zina was in critical condition out at Harbor UCLA. All of them shot at Zina’s home with a 9mm handgun registered to Del. The detectives said the young woman’s chances of survival didn’t look good.

“Maybe you’d like to take a break,” Luckman said.

“A break’s not going to change anything. I’ve told you all I know. The man said he’d fucked up but didn’t tell me how. He said his girls were dead and that it was his fault. Then he hung up. That’s it. There is no more.”

“He didn’t say he’d just shot his wife and daughter?”

“No.”

“Or that he was about to take his own life?”

More forcefully this time: “No.”

“And you have no idea why Mr. Curry would have wanted to harm either person.”

“None whatsoever.”

“Were there any problems in the home that you were aware of? Were Mr. Curry and his wife getting along?”

“Yes. I mean, I think they were. Del loved Noelle. And I’m sure she loved him.”

That had always been Gunner’s understanding, anyway. Del didn’t talk much about his family life, even with Gunner. When he did, however, it was usually to recount a story that made everything on that side of his world sound either funny or touching, Noelle in particular. On those rare occasions Gunner saw her, at family barbecues or holiday dinners, Del’s wife—a tall, heavyset woman with flawless dark skin and a dazzling smile—gave him no reason to suspect she was anything but happy.

“What about money? Could Mr. Curry have been in any kind of financial trouble?”

“Money was always an issue, sure. And lately, more so than ever, I suppose. But was he hurting bad enough to do something like this?” Gunner shook his head, unable to fathom the possibility. “I can’t see it.”

And yet, something had driven Del to do what he’d done. Something larger and more pitch black than anything Gunner, prior to today, could have ever dreamt his cousin was coping with. Unless things hadn’t really gone down the way the cops were saying they had. Luckman and his partner didn’t seem to have any doubts whatsoever, but Gunner asked the detective again if there was a chance—any chance at all—that somebody other than Del had done the shooting.

“We can’t answer that conclusively until we’ve completed our investigation, of course,” Luckman said. “But right now? Based upon witness accounts and the evidence at the scene? I’d say there’s little to no chance that anyone other than Mr. Curry was involved.”

The “witness accounts” he was referring to were statements they’d received from two neighbors of Del’s daughter, who’d reported hearing a loud argument taking place in the house, followed shortly thereafter by gunfire. One of these people had called 911, and paramedics and police had arrived on the scene just in time to hear one more shot, the one that had apparently ended Del’s life.

The ghetto bird cutting circles in the air above Zina’s home hadn’t been interested in Gunner’s cousin, at all. Its focus, and that of the news ‘copters accompanying it, was another crime altogether, just blocks away. Which was how shit often went down in Gunner’s world: one disaster after another, packed as tightly together as rounds in a magazine. The cruel coincidence only served to make Del’s death just that much harder for Gunner to swallow.

As he was the last person to speak to Del before he died, Luckman and his partner were looking to Gunner for answers, and they seemed willing to lean on him all day and night to get them. If Gunner couldn’t explain what had caused the bloodbath in Zina’s home, and she died before she could make a statement, maybe there never would be an explanation.

They kept him down at the Southeast station for another forty minutes, Luckman finally content to answer more questions than he asked. In the end, both he and Gunner left the little interrogation room as confused as they had been going in.

Gunner drove out to Harbor UCLA hospital on automatic pilot, no more aware of what he was doing than a rock was of rolling downhill. A host of news reporters had tried to get a statement out of him at the station while he was sleepwalking to his car, but they would have had better luck drawing a quote from one of the wax figures at Madame Tussauds. He vacillated over which inalienable fact was more difficult to believe: that Del was dead, or that he’d killed himself after turning a gun on both his wife and daughter.

Either way, Gunner knew his world had just narrowed dramatically. Del hadn’t been his only family, but he had been Gunner’s closest. Gunner had lost contact with his younger brother, John, almost a year ago now—the last he’d heard, the retired Navy man had been living somewhere just outside of Portsmouth, Virginia—and his baby sister, Jo, was up in Seattle. He had a nephew here in Los Angeles—his late sister Ruth’s son Alred—“Ready,” as he was known on the street, was a bona fide gangster Gunner treated like a rabid dog on too short a chain. Del, by contrast, was someone he saw or spoke to over the phone at least two or three times a week. The only child of his mother Juliette’s brother Daniel, Del was the nearest thing Gunner had to a confidant.

And yet, as Gunner thought about it now, he realized that their frequency of contact had dropped off precipitously over the last two months or so. He’d last seen his cousin only three days earlier, at the Acey Deuce bar where they often hooked up, but prior to that, the two men hadn’t spoken in almost two weeks. As it was, that last night at the Deuce, they’d had almost nothing to say to each other; even the banter Gunner and Del liked to exchange with the bar’s loud-mouthed owner Lilly Tennell had been decidedly muted and uninspired. Looking back, Gunner could see that a space had opened up between them, a wedge of silence and secrecy that had crept up on them like a ghost, and it shamed him that it had taken him this long to become aware of it.

He’d been too caught up in his own troubles to care if Del had developed any of his own. Maybe if he’d tried to talk to Del about the things that had been weighing on his own mind lately, his cousin would have felt obliged to reciprocate, giving Gunner a chance to defuse whatever it was that had driven him to murder-suicide. But men didn’t open themselves up to each other that way, especially when times were hard and complaining just made you feel like an old woman. Pride shut you down instead and made you pretend all was well, feeding the false hope that, no matter the odds against it, you could fix whatever was broken all by yourself.

Still operating under a cocktail fog of guilt and reflection, Gunner parked the Cobra in the hospital lot and made his way up to the ICU where Zina Curry—assuming the girl was still alive—waited. He knew it would be some time before she’d be able to answer the questions he and the police had for her, if she ever recovered from her injuries enough to do so at all, but the girl was unmarried and childless and, as far as he knew, Gunner was her last living relative in Los Angeles. Somebody had to be there when she either opened her eyes again or passed on. It didn’t matter that he and Zina were, for all practical purposes, strangers—he couldn’t remember the last time he’d seen her, and what little Del used to say about her hadn’t left him with anything more than a vague idea of what kind of foolishness she liked to watch on television or how much weight she’d lost or gained; she was family, and a man didn’t let family go unrepresented in hospital waiting rooms. Ever.

When he found the nurses’ desk on the third floor, they told him Zina had just come out of surgery and was still on her way to the ICU recovery room. They couldn’t comment on her condition. He asked to speak with the doctor who’d performed her surgery and then followed the nurses’ directions to the waiting room, which was every bit as claustrophobic and depressing as he’d feared it would be. The walls were bare, the magazines were all unreadable, and the muted television was tuned to a cooking show he would have traded for a cartoon had he access to the remote. The room’s only other occupant, a fat white woman in a yellow blouse and gray sweatpants, sat in one corner crying the blues into a cell phone, making a mockery of a sign mounted directly over her head forbidding the use of such devices.

Gunner figured he could live with her ignorance for a good five minutes; after that, the lady was going to need a new cell phone.

He had calls of his own to make. Del’s parents, Daniel and Corinne, had to be informed of his death and Noelle’s, and the condition of their granddaughter. He would wait until he spoke to Zina’s surgeon before contacting them in Atlanta. With any luck, they would absolve him of any further responsibility and volunteer to pass the word on to anyone else in the family who needed to be notified. It was a selfish wish, but that was what he wanted.

The big woman in the gray sweatpants and knockoff running shoes closed up her phone and waddled out of the room, leaving Gunner free to replumb the depths of his grief and confusion in relative peace. He tried the thought on for size one more time: Del was dead, and he’d murdered Noelle and tried to kill Zina.

It still made no sense.

It made no sense at all.