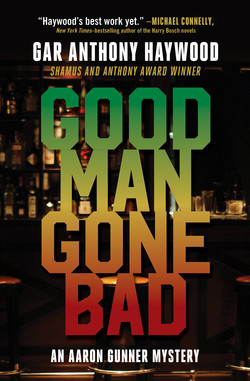

Читать книгу Good Man Gone Bad - Gar Anthony Haywood - Страница 14

Оглавление5

“IT SHOULD BE DEUCY, with a Y,” the stranger said again, because nobody had acknowledged him the first time.

“Excuse me?”

“The name of the bar. It should be The Acey Deucy, with a Y at the end. Not The Acey Deuce.”

He was a newcomer here, everyone could see that, so his ignorance was forgivable. But Lilly Tennell, who had been the Central Los Angeles bar’s sole owner and operator since her husband J.T. had been murdered in it going on twenty years ago, did not always have patience for those who made this observation about its name. It was a slow and somber night at the Deuce as it was, owner and regular patrons alike dealing with the death of one of their own, and Lilly didn’t need any added incentive to be uncivil.

“We lost the Y in a fire,” she said, her mouth an angry red line against the inky black of her face. “Summer of ’73. Some fool use’ to rent the building next door burned up his top two floors and part of our roof, settin’ an old space heater too close to a pile’a clothes, and the fire took the Y in our sign up there with it. ’Course, we didn’t have no insurance, took us eight months to raise the six hundred the man said it would cost to put the damn Y back, and by that time, people were already callin’ the place the Deuce and likin’ the sound of it too much to change. Okay?”

Sitting at the bar two stools off the stranger’s left elbow, Gunner had heard Lilly tell the story at least a half dozen times before, but never with such open resentment. Tonight, with all who knew him grieving for Del and the family he’d allegedly laid to waste, things the barkeep usually found only mildly annoying got a real rise out of her instead. She didn’t know this chunky, red-haired brother in the Sears delivery truck uniform and had no reason to dislike him, but in choosing this moment in time to suggest she’d misspelled the name of her own establishment, he’d yanked on the proverbial tiger’s tail.

To his credit, and to the relief of Gunner and the four other customers in the bar, the man recognized his mistake and just said, “Okay.” Lilly’s piercing gaze dared him to do otherwise.

The house fell back into quiet, sans the sound of Roberta Flack’s voice floating at the outer edges of everyone’s consciousness, until the stranger finished his drink and walked out. Then, amazingly, the bar grew quieter still. Lilly stood behind the counter of the bar just off to Gunner’s right, drying a glass with a towel like somebody wringing a chicken’s neck.

“It’s called the Deuce ’cause I wanna call it the Deuce,” she said under her breath, no more aware she was speaking out loud than she was of the glass she was torturing. “I gotta explain to one more motherfucka why there ain’t no Y in the goddamn name, I’ll lose my mind, I swear to God…”

“Lilly,” Gunner said.

“This is my place. I’ll call it whatever the fuck I wanna call it.”

“Lilly,” Gunner said, more forcefully this time. The big woman swung her fat head around to face him, almost too fast for the wig she always wore to follow. “What?”

“Never mind him. I need to ask you some questions.” He turned on his stool to regard the other four patrons in the bar, all people he knew as regular customers here: Howard Gaines, Eggy Jones, Jackie Scarborough, and Aubrey Coleman. “That goes for all of you.”

“What kind of questions?” Jackie asked from the booth she was sharing with Aubrey. She was small and compact, a single mother of three with a pretty face and a dancer’s body who worked as an RN out at Kaiser Hospital downtown, and she always came into the Deuce suspicious of everyone’s intentions.

“You know what kind of questions,” Gunner said with some irritation. “I want to talk to you about Del.”

“If you’re thinkin’ we know something about what happened today…” Lilly started to say.

“Man, we just as much in the dark as you are,” Howard completed the thought for her as he and Eggy Jones left their table in the corner to join Gunner at the bar. Aubrey and Jackie, having no such compunction, stayed in the booth where they were.

“Maybe so,” Gunner said. “But I’m going to ask my questions anyway, and you’re going to answer them.”

He looked directly at Aubrey, he of the post-doctoral education and professorial manner, the one person in the house most likely to object to being bullied in this way, and waited to hear a complaint. Aubrey offered none.

“Okay. Go ahead,” Lilly said. She stepped right up to Gunner’s position at the bar and set the glass she’d been polishing down on the countertop in front of him, like a dare.

“You’ve all heard the news. You know what they say he did. They say he killed his wife and tried to kill his daughter, then shot himself to death.” Gunner turned this way and that to regard each person in turn. “They say it couldn’t have happened any other way, but I can’t believe it. Maybe I’m a fool. Maybe one of you knows something, anything, that I don’t know that could help me to believe it. Could Del have really done such a thing? Is it possible?”

“Anything’s possible,” Eggy Jones said. His Coke-bottle eyeglasses reflected neon light from the illuminated beer signs hanging at Lilly’s back behind the bar.

“With all due respect, that’s bullshit,” Gunner said. “We all have our limits and Del had his. The Del I thought I knew could never have hurt anyone, least of all Noelle and Zina. But maybe he’d changed without my noticing. I’ve been thinking about it a lot today and I realize it’s been a long time since he and I last talked—really talked—about anything.”

“And you think he would’a talked to us instead?” Howard asked. The career custodian was the oldest man in the room and the most visibly weary, and what he lacked in intellect he more than made up for in heart.

“I don’t know,” Gunner said. “That’s what I’m trying to find out. When was the last time any of you saw him?”

When no one spoke up, he turned to Lilly.

“He was in here just the other night. You was here, you know,” the barkeep said.

“You hadn’t seen him since?”

“No.”

Gunner looked to the others. “And you?”

“I saw him in here that night, too,” Jackie said. “But we didn’t talk.”

“I hadn’t seen him in over a week,” Aubrey said. “And the last time wasn’t here. I saw him pumping gas near the house. We said hello, and that was about it.”

“I don’t remember the last time I seen ’im,” Howard said.

“Before the other night in here, you mean?” Lilly asked.

“Huh?”

“You was here Friday night, too, same as Gunner and Jackie.”

“Oh, yeah, that’s right,” Howard said, nodding his head. “I was, huh?” Here at the Deuce, the man was always feeling the effects of a drink or two just short of his limit, so straight answers to even the simplest of questions were rarely expected of him.

“Did you talk to him?” Gunner asked, when Howard made no attempt to elaborate. He hadn’t seen the two men together that night, but he’d left while they were both still here, leaving the possibility open they’d connected after he was gone.

“Did we talk? Yeah, I guess we did.” Howard shrugged. “We must’ve talked. Me an’ Del always got somethin’ to say to each other.”

“So what did you talk about, Howard?”

“I dunno. Just the usual. The Lakers. Movies. That boy got knifed to death at Home Warehouse. You hear about that? The security guard?”

Gunner had, though he couldn’t see the story’s relevance to the present discussion. The teenage guard had caught a thirty-eight-year-old day laborer trying to sneak a set of drill bits out of the hardware chain’s Van Nuys location and died when the would-be thief attacked him with a box cutter. According to the news reports Gunner had seen, the guard’s rate of pay was $9 an hour, while the cost of the drill bits was $13 and change.

“I heard about it. What else?”

“What else?”

“What else did you and Del talk about? Anything?”

Howard shook his head. “No. ’Least, I can’t think of nothin’ else.”

Gunner finally turned to Jones. “What about you, Eggy? When did you last see Del?”

“I been trying to remember, exactly. But I can’t. It’s been a long time, Gunner, I can tell you that.” His sorrowful expression was all but a plea that Gunner not press him on the matter.

Acquiescing, Gunner brought his questioning full circle and said to Lilly, “Okay. Here on Friday was the last time you saw him. What did you talk about? He must’ve said something to you.”

“’Course he said something to me. You was sittin’ right next to him, you heard what he said just as clear as me.”

“I’m not talking about while I was here. That was nothing, just the usual bullshit. I’m talking about before I arrived or after I left. What, does all conversation fucking cease in here when I’m not around?”

Lilly’s eyes flared in the dark. “Say again?”

Gunner had let his impatience get the better of him and pushed the last person in the bar he wanted to alienate. Even taking into account all he was dealing with tonight, Lilly wasn’t going to tolerate his disrespect for a minute.

“I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have said that.”

“You got that right. You wanna try again?”

Sufficiently humbled before the others, Gunner said, “Did you and Del talk, either before I came in here Friday or after I went home?”

“Yes. We talked after you left.”

“About what?”

“He asked me if I missed J.T.”

“J.T.?”

“Yeah. I don’t know how we got started—I think he just asked straight up, out of the blue: ‘Do you miss J.T.?’ And I said hell, yes, I miss him. Ain’t a day goes by I don’t think about that man.”

“He say why he asked?”

“No. All he said was, he didn’t know how I do it. Go on livin’ after somebody I’d been with all those years was gone. He said he’d never make it.”

“If something happened to Noelle, you mean?”

“Yeah.”

“Can you remember what he said, exactly?”

“Exactly?” Lilly braced her arms against the bar, let out a sigh befitting her considerable bulk. “I think he said somethin’ like, ‘I’d never make it alone, it was me.’ And I said, well, God willing, you ain’t never gonna have to. And then he just kind’a smiled and didn’t say nothin’ else.”

“He smiled?”

“Yeah. I remember thinkin’, ‘What’d I say was funny?’ I was gonna ask, but I got called away by somebody—” She turned to Gaines. “I think it might’a been you, Harold—so I never got the chance. He must’ve left soon after that.”

“Damn,” Harold said. “You don’t s’pose he was already thinkin’ about what he was gonna do?”

“We don’t know that he did anything, yet,” Gunner said. But he only said it because somebody here had to, lest his faint hope it was true melt away to nothing.

“But if he didn’t do it—” Howard said.

“I’ll find out who did. You can bank that.”

Gunner went around the room, giving everyone but Lilly, who had long ago committed his contact info to memory, a business card. “If you can think of anything that might help, anything you might have seen or heard that could explain what happened today, call me. Day or night. Understood?”

Five solemn nods told him it was. Gunner went back to his seat at the bar, and Howard and Jones returned to their table just as someone pushed the Deuce’s door open and stepped tentatively inside. Kelly DeCharme squinted in the smoky dark, found the man she was looking for, then eased her way forward to join Gunner at the bar, every eye in the house moving right along with her.

“Hey,” he said.

“Hey,” she said, barely above a whisper, signaling her intent to treat him with the utmost care. He’d given her the news about Del earlier in the day, so she understood how fragile he was likely to be.

She started to take the stool beside his, but he stood up and said, “Not here. Let’s get a booth.”

They took one in the far corner of the bar, where they wouldn’t be overheard and the curiosity the white woman still aroused here, even though she’d met Gunner at the Deuce several times before, would be easier to ignore. No sooner were they settled in than Lilly, as if tied to Gunner by a string, appeared to ask if Kelly would like something to drink. Kelly ordered a Rum and Coke, and Gunner asked for another Wild Turkey, wet.

“I still can’t tell if she likes me or not,” Kelly said as the barkeep walked away.

“Lilly? She likes you fine,” Gunner said. “If she didn’t, there’d be no doubt in your mind.”

Kelly reached out to put her hand in his. “Any news on Del’s daughter?”

“Not as of thirty minutes ago, when I last checked. She still hasn’t regained consciousness, and her doctors remain uncertain that she ever will.”

“And the police still think he did it?”

“Yes.”

“But why? Why would he do something so horrible?” Having met Del on a number of occasions, the idea of him shooting his wife and daughter, and then killing himself, seemed almost as preposterous to her as it did to Gunner.

“I don’t know. I wish to God I did. His office assistant says his business had been off for a while, but whose business hasn’t been? And as for things at home, she says the only trouble there that she’s aware of are some issues he and Noelle may have been having with Zina lately. Any of that sound like sufficient motive for a murder-suicide to you?”

“No. It doesn’t.” And then the lawyer in her added: “At least, not on the surface.”

But the surface was all Gunner had at this point. He had hoped someone at the Deuce might know something he didn’t, something to suggest there was an explanation for what had happened at Zina’s home that didn’t put the death of two people and the near-fatal shooting of another squarely at his cousin’s feet, but the exact opposite had occurred. Lilly had Del talking about his wife three days ago like Noelle was already dead, and if that didn’t suggest premeditation on his part, it at least pointed to the possibility of marital discord, which was almost just as damning. Had Noelle been about to leave him, Del would have hardly been the first man Gunner had heard of to decide his family would be better off dead than apart. Gunner still didn’t believe his cousin was capable of murder, but so far, what evidence he had scraped together was only giving him greater reason to accept that conclusion, not less.

“Have you heard back from his parents yet?” Kelly asked.

“They caught a 7:30 red-eye scheduled to arrive at LAX tomorrow morning at 9:45. I told his father I’d pick them up and take them wherever they want to go.” Anxious to change the subject, Gunner said, “But we didn’t call this meeting to talk about Del, we called it to talk about your client. You want to go first or should I?”

“You go,” Kelly said.

Gunner gave her the rundown of his interview with Tyrecee Abbott that afternoon, occasionally consulting the notes he had taken shortly afterward.

“Shit,” she said when he was done.

“Yeah. A tower of support for her man, she wasn’t.”

“And she can’t help us with an alibi.”

“Not personally. But she might know somebody who can.”

“Woods?”

“That would be my first guess. She insisted it was just her and Stowe at the apartment that night, but she was either lying to me or I’ve lost my capacity to judge such things.”

“And your second guess?”

“Her mother. I got the impression Ms. Abbott keeps Tyrecee on a very short leash and doesn’t miss much where her daughter and her friends are concerned. If I don’t get anything useful out of Woods tomorrow, she might be worth talking to next.”

Kelly downed the last of her drink in one gulp and nodded, endorsing Gunner’s logic.

He had already spoken to Eric Woods once, over lunch four days ago, but he was anxious now to have Stowe’s boy explain the discrepancies between his account of how Stowe had spent the hours before Darlene Evans’s death and the one Tyrecee Abbott had given him this morning.

“Cheer up,” Gunner said, noting Kelly’s despondency. “Little Tyrecee wasn’t a total bust. Her shocking lack of affection for him aside, she at least stated without reservation that she’s never seen your client with a gun.”

Kelly nodded again, cheered not a whit.

“Of course….”

“Of course, we might have been better off if she’d said just the opposite.”

“Well, sooner or later, we are going to have to put the murder weapon in Stowe’s hands to explain his prints on it, and do it in a way that doesn’t somehow prove he used it to shoot the deceased.”

It was easily the most daunting aspect of their defense efforts. Stowe had no recollection of ever seeing the unregistered Taurus used to murder Evans, let alone handling it, and no one Gunner had yet spoken to could venture a guess as to how or when he might have come in contact with it. If Gunner and Kelly couldn’t offer a jury an innocent explanation for his fingerprints being on the gun, even an alibi placing Stowe miles from Empire Auto Parts when Evans was killed might not be enough to win him an acquittal.

“I’m visiting Harper again Wednesday,” Kelly said. “Hopefully, he’ll have remembered a thing or two that will be useful to us since the last time we talked. His memory of those two days has to come back to him eventually.”

“If it hasn’t already, you mean.”

She shot him a wary side-eye. “Excuse me?”

“Well, there is a chance he remembers more about all of it than he’s been telling us, isn’t there? I mean, if we’re being honest about it?”

“No.”

“I’m just saying.”

“No, Aaron. Positively not. But if that’s what you think—”

“I didn’t say that’s what I think. I’m just saying we’d be wise to consider the possibility that he hasn’t been entirely truthful with us. Either because he did in fact commit the crime himself, or is protecting someone else who did.”

“Harper didn’t kill Darlene Evans, Aaron. And he’s told us everything he knows or can remember about her murder. If I didn’t believe that, I would have never taken his case in the first place.” Gunner started to respond, but she pushed on: “You haven’t spoken to him yet. I have. He’s been telling us the truth. I know it and his father knows it.”

Stowe’s father was Harper Stowe Jr., the man who had actually retained the services of Kelly’s firm. He was a sixty-six-year-old retired mechanical engineer who cast a brown bear’s shadow and spoke like every word was a dollar out of his pocket, and both his bearing and physical appearance—from his well-tailored clothes to his trim white goatee—were unapologetically imperious. Gunner had met him only once, at a brief meeting with Kelly in her office ten days ago, but once had been enough to be suitably antagonized.

“Okay. I’m convinced,” Gunner said.

“No. You’re not. But that’s okay. I didn’t hire you to drink the Kool-Aid. I hired you to find out the truth.”

“And if I find out your client’s guilty?”

“Then Harper Junior is going to be one very unhappy man. When was the last time you called Samuel Evans?”

“He doesn’t want to talk to me.”

“Of course he doesn’t. Nobody on our interview list does. But since when is that an excuse to stop trying?”

“Who said I was going to stop trying?”

“You’ll call him again tomorrow, then.”

“I already had plans to.”

Gunner had been trying to question Darlene Evans’s widower for days now, and only Tyrecee Abbott had proven more reluctant to cooperate. His reasons for wanting to talk to Samuel Evans were all too obvious, and being a likely suspect in his wife’s murder, as the spouse of a homicide victim always was, helping Gunner along probably did not sit particularly well with the man.

“I’d like another,” Kelly said, gesturing with her empty glass. Gunner waved Lilly over and ordered them both a refill, the bartender for once coming and going without her and Gunner exchanging any of their customary extraneous banter.

In Lilly’s absence, Gunner and Kelly sat there in silence for a moment, each gripping the other’s hand as if for the last time. Kelly studied Gunner’s face in the bar’s muted light, and asked, “Are you going to be okay?”

“No,” he said, lacking any incentive to lie. “I don’t think I’m going to be okay for quite a while.”

He wanted to go on talking, to tell her everything he knew about Del Curry and everything he remembered about him. All the fights they’d had over things big and small, the laughter they’d shared first at one man’s expense, then the other’s, over and over, round and round, even when the target of all the levity had every right to be crying instead. He wanted to count for Kelly all the times Del had saved his ass, either by setting his head on straight when it was about to spin off or by having his back, both literally and figuratively, when Gunner was up against something or someone he couldn’t take on alone. There were a thousand stories to tell, a thousand things to say about his dead cousin that Gunner wanted, needed to… say But he couldn’t bring himself to say them now. He was afraid of what might happen if he tried.

So he just held on tight to Kelly’s hand and cried, instead.