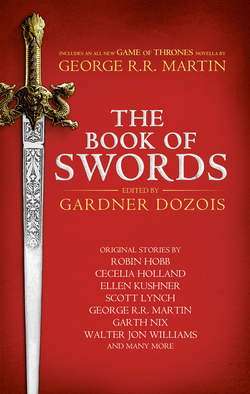

Читать книгу The Book of Swords - Gardner Dozois, Гарднер Дозуа, Gardner Dozois - Страница 11

HER FATHER’S SWORD

ОглавлениеTaura shifted on her lookout’s platform. Cold was stiffening her, and calling two skinny logs tied across a couple of outreaching branches a “watchtower platform” was generous. A flat surface would have been kinder to her buttocks and back. She shifted to a squat and checked the position of the moon again. When it was over the Hummock on Last Chance Point, her watch would be over and Kerry would come to relieve her. In theory.

They’d given her the least likely point of entry to the village. Her tree overlooked the market trail that led inland, to Higround Market where they sold their fish. Unlikely that Forged would come from this direction. The kidnapped people had been forced from their homes and down to the beach. Past their burned fishing boats and the ransacked smoking racks for preserving the catch the captured townsfolk had gone. A boy who had dared to follow his kidnapped mother said the raiders had forced their folk into boats and rowed them out to a red-hulled ship anchored offshore. As they had been taken to the sea, so they would return from the waves.

Taura had seen them go from her hiding place in the big willow that overlooked the harbor. The raiders hadn’t seemed to care who they took. She’d seen old Pa Grimby, and Salal Greenoak carrying her nursing baby. She’d seen the little Bodby twins and Kelia and Rudan and Cope. And her father, roaring and staggering with blood sheeting down the side of his face. She had known the names of almost every captive. Smokerscot was not a big village. There were perhaps six hundred folk here.

Well. There had been perhaps six hundred. Before the raid.

After the raid, Taura had helped stack the bodies after they’d put out the fires. She’d stopped counting after forty, and those were just the people in the stack on the east end of the village. There’d been another pyre near the rickety dock. No. The dock wasn’t rickety anymore. It was charred pilings sticking out of the water next to the sunken hulks of the small fishing fleet. Her father’s boat was among them. The changes had all happened so fast that it was hard to remember them. Earlier tonight, she’d decided to run back home and get a warmer cloak. Then she’d recalled that her home was wet ash and charred planks. It wasn’t the only one. The five adjoining houses had burned, and dozens of others in the village. Even the Kelp’s grand house, two stories, not even finished, was now a smoking pile of timbers.

She shifted on her platform and something poked her. She’d sat on her whistle on its lanyard. The village council had given her a cudgel and a whistle to blow if she saw anyone approaching. Two blasts from her whistle would bring the strong folk from the village with their “weapons.” They would come with their poles and axes and gaff hooks. And Jelin would come, wearing her father’s sword. What if no one came to her whistle? She had a cudgel. As if she were going to climb down from the tree and try to bash someone. As if she could bear to club people she had known since she was a babe.

A rhythmic clopping reached her ears. A horse approaching? It was past sundown, and few travelers came to Smokerscot at any time, save the fish buyers who came at the end of summer to dicker for the fall run of redfish. But in winter, and after dark? Who would be coming this way? She watched the narrow stripe of hard-packed earth that led through the forested hills to Higround, peering through the darkness.

A horse and rider came into sight. A single rider and horse, bearing a lumpy bundle on the saddle before him and two bulging panniers behind him. As she stared, the bundle wriggled and gave a long whine, then burst into the full-throated fury of an angry child.

She blew a single blast on her whistle, the “maybe it’s danger” signal. The rider halted and stared toward her perch. He did not reach for a bow. Indeed, it looked to be all he could do to restrain the child that he held before him. She stood, rolled her back a bit to remove some of the chill-stiffened kinks, and began the climb down. By the time she reached the ground, Marva and Carber had appeared. And Kerry, long past his time to come and relieve her. They stood with tall poles, blocking the horse’s path. Over the sound of the child’s wailing, they were trying to question him. By their torches, she saw a young man with dark hair and eyes. His thick wool cloak was Buck blue. She wondered what was in his horse’s panniers.

He finally shouted, “Will someone take this boy from me? He says his name is Peevy and his mother’s name is Kelia! He said he lived in Smokerscot, and pointed this way. Does he belong here?”

“Kelia’s boy!” Marva exclaimed, and came closer to examine the kicking, wriggling child. “Peevy! Peevy, it’s me, Cousin Marva. Come to me, now! Come to me.”

As the man started to lower the child from his tall black mount, the small boy twisted to hit at him shouting, “I hate you! I hate you! Let me go!”

Marva stepped back suddenly. “He’s Forged, isn’t he? Oh, sweet Eda, what shall we do? He’s just four, and Kelia’s only child. The raiders must have taken him when they took her. I thought he’d died in the fires!”

“He’s not Forged,” the rider said with some impatience. “He’s angry because I had no food for him. Please. Take him.” The youngster was kicking his heels against the horse’s shoulder and varying his now-incoherent wails with shouting for his mother. Marva stepped forward. Peevy kicked her a few times before she engulfed him in her arms. “Peevy, Peevy, it’s me, you’re safe! Oh, lovey, you’re safe now. You’re so cold! Can you calm down?”

“I’m hungry!” the boy shouted. “I’m cold. Mosquitoes bit me and I cut my hands on the barnacles and Mama threw me off the boat! She threw me off the boat into the dark water and she didn’t care! I screamed and the boat left me in the water. And the waves pushed me and I had to climb up the rocks, then I was losted in the wood!” He aired all his grievances in a child’s shrill voice.

Taura edged up beside Kerry. “Your watch, now,” she reminded him.

“I know that,” he told her in disdain as he stared down at her. She shrugged. She’d reminded him. It wasn’t her task to see he did his share. She’d done hers.

The stranger dismounted. He led his horse into the village as if certain of that right. Taura marked how everyone fell in around him, forgetting to challenge him at all. Well, he wasn’t Forged. A Forged one would never have helped a child. He gave the boy in Marva’s arms a sympathetic look. “That explains a great deal.” He looked over at Carber. “The boy darted out of the forest right in front of my horse, crying and shouting for help. I’m glad he has kin still alive to take him in. And sorry that you were raided. You aren’t the only ones. Up the coast, Shrike was raided last week. That’s where I was bound.”

“And who are you?” Carber demanded suspiciously.

“King Shrewd received a bird from Shrike and dispatched me right away. My name is FitzChivalry Farseer. I was sent to help at Shrike; I didn’t know you’d been raided as well. I cannot stay long, but I can tell you what you need to know to deal with this.” He lifted his voice to address those who had trooped out to see what Taura’s whistle meant. “I can teach you how to deal with the Forged ones. As much as we know how to deal with them.” He looked around at the circle of staring faces, and said more strongly, “The king has sent me to help folk like you. Man your watch stations, but call a meeting of everyone else in the village. I need to speak to all of you. Your Forged ones may return at any time.”

“One man?” Carber asked angrily. “We send word to our king that we are raided, that folk are carried off by the Red-Ship Raiders, and he sends us one man?”

“Chivalry’s bastard,” someone said. It sounded like Hedley, but Taura couldn’t be certain in the dusk. Folk were coming out of the houses that remained standing and joining the trailing group of people following the messenger and his horse. The man ignored the slur.

“The king did not send me here but to Shrike. I’ve come out of my way to bring the boy back to you. Did the raiders leave your inn standing? I’d appreciate a meal and a place to stable my horse. Last night we were out in the rain. And the inn might be a good place for folk to gather to hear what I have to say.”

“Smokerscot never had an inn. Not much call for one. The road ends here, at the cove. Everyone who lives here sleeps in his own bed at night.” Carber sounded insulted that the king’s man could have imagined Smokerscot had an inn.

“They used to,” Taura said quietly. “Now a lot of us don’t have beds to sleep in.” Where was she going to sleep tonight? Probably at her neighbor’s house. Jelin had offered her a blanket on the floor by his fire. That was a kind thing to do, her mother had said. The neighborly thing to do. Her younger brother Gef had echoed her words exactly. And when Jelin had asked for it, they’d given him Papa’s sword. As if they owed it to him for doing a decent thing. The sword was one of the few things they had saved from their house when the raiders set it on fire. “Your brother is too young, and you will never be strong enough to swing it. Let Jelin have it.” So her mother had said and sternly shushed her when she’d discovered what they had done. “Remember what your father always said. Do what you must to survive and don’t look back.”

Taura recalled well when he’d said that. He and his crew of two had dumped most of their catch overboard so they could ride out a sudden storm. Taura thought it was quite one thing to surrender something valuable to stay alive and quite another to give away the last valuable thing they had to a swaggering braggart. Her mother might say she’d never be strong enough to swing it, but she didn’t know that Taura could already lift it. Several times when her father had taken it out of an evening to wipe it clean and oil it fresh, he’d let her hold it. It always took both her hands, but the last time, she’d been able to lift it and swing it, however awkwardly. Papa had given a gruff laugh. “The heart but not the muscle. Too bad. I could have used a tall son with your spirit.” He’d given Gef a sideways glance. “Or any sort of a son with a mind,” he’d mutter.

But she had not been a son, and instead of her father’s size and strength, she was small, like her mother. She was of an age to work the boat alongside her father, but he’d never taken her. “Not enough room on the deck for a hand who can’t pull the full weight of a deckhand’s duties. It’s too bad.” And that was the end of it. But still, later that month, he’d again let her lift the bared sword. She’d swung it twice before the weight of it had drawn the point of it down to the earth again.

And her father had smiled at her.

But now Papa was gone, taken by the Red-Ship Raiders. And she had nothing of his.

Taura was the elder; the sword should have been hers, whether she could swing it or not. But the way it had happened, she’d had no real say. She’d come back from dragging bodies to the pyre, come back to Jelin’s house to see the sword standing in its sheath in the corner, like a broom! She and her mother and Gef could sleep on the floor of Jelin’s house, and he could have the last valuable item her family owned. And her mother thought that good. How was that a fair trade? It cost him nothing for them to sleep on his floor. Clearly her mother had no idea of how to survive.

Don’t think about that.

“… the fish-smoking shed,” Carber was saying. “It’s mostly empty now. But we can start up the fires for heat instead of smoke and gather a lot of folk there.”

“That would be good,” the stranger said.

Marva smiled up at him. Peevy had stopped struggling. He had his arms around his cousin’s neck and his face buried in her cloak. “There is room in our home for you to sleep, sir. And too much room now in our goat shed for your horse.” Her smile twisted bitterly. “The raiders left us few animals to shelter. What they did not take they killed.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” he said wearily, and it seemed to Taura it was a tale he had heard before and perhaps that was what he always replied to it.

Carber sent runners through the village, calling the folk to gather in the fish-smoking shed. Taura felt childish satisfaction when he ordered Kerry to take up his watch. She followed the crowd to the shed. Several families were already sheltering there. They had a fire going and had set up makeshift households in different parts of the shed.

Had her mother thought of coming here? At least they would still be a separate family, a household. They would still have had Papa’s sword.

Carber tipped over a crate for the messenger to stand upon, as the villagers gathered in the barn-like shed that always smelt of alder smoke and fish. The folk trickled in slowly and Taura could see the stranger’s impatience growing. Finally he climbed onto his small stage and called for silence. “We dare not wait any longer. The Forged will be returned to your village at any time now. That we know. It is a pattern the Red-Ship Raiders have followed since they first attacked Forge and returned half its inhabitants as heartless ghosts of themselves.” He looked down and saw the confusion on the faces that surrounded him. He spoke more simply. “The Red Ships come. The raiders kill and they plunder, but their real destruction comes after they have left. They carry off those you love. They do something to them, something we don’t understand. They hold them for a time, then give them back to you, their families. They will return tired, hungry, wet, and cold. They will look like your kin and they will call you by name. But they will not be the folk who left here.”

He looked out over the gathered folk and shook his head at the hope and disbelief that his words had stirred. Taura watched him try to explain. “They will recall your faces and names. A father will know his children’s names and a baker will recall her pans and oven. They will seek out their own homes. But you must not let them into your village or homes. Because they will care nothing for you, only for themselves. Theft and beatings, murders and rape will come with them.”

Taura stared up at him. His words made no sense. Other faces reflected the same confusion, for the man shook his head sorrowfully. “It’s difficult to explain. A father will snatch food from his little boy’s mouth. If you have something they want, they will take it, regardless of how much violence they must use. If they are hungry, they will take all the food for themselves, drive you from your homes if they wish shelter.” His voice dropped as he added, “If they feel lust, they will rape.” His gaze roved over them, then he added, “They will rape anyone.”

He shook his head at the disbelief on their faces. “Listen to me, please! Everything you have heard about the Forged, every rumor you have heard is true. Go home and fortify your homes now. Tighten the shutters on your windows, be sure the bars on your doors are strong. Organize the people who will protect this village. Assemble them. Arm yourselves. You’ve set a watch. That’s good.”

He drew breath and Taura called into the pause, “But what are we to do when they come?”

He looked directly at her. Possibly he was a handsome man, when he was not cold and weary. The tops of his cheeks were red and his dark hair lank with rain or sweat. His brown eyes were agonized. “The people who went away are not coming back to you. The Forged will not change back into those people. Ever.” His next words came out harshly. “You must be prepared to kill them. Before they kill you.”

Abruptly, Taura hated him. Handsome or not, he was talking about her father. Her father, big, strong Burk, coming back from a day’s fishing, unarmed and unprepared to be clubbed down and dragged away. When her mother had screamed at her to run and hide, she had. She’d been so sure that her father, her big strong Papa, would fight his way clear of his captors. So she had done nothing to help him. She’d hidden in the thicket of the willow’s branches while he was dragged away.

The next morning, she and her mother found each other when they returned to the remains of their house. Gef had stood outside their burned home, wailing as if he were five instead of thirteen. They’d let him stand and weep. Both Taura and her mother knew there was no getting through to her simple brother. In a light drizzle of freezing rain, they’d poked through the scorched timbers and the thick ash of the fallen thatch that had been their home. There had been little to salvage. Gef had stood and bawled as Taura and her mother had poked through the smoldering wreckage. A few cooking pots and three woolen blankets had been in a heavy cupboard that had somehow not burned through. A bowl and three plates. Then she’d found, sheltered beneath a fallen timber and unscorched, her father’s sword in its fine sheath. The sword that would have saved him if he’d had it with him.

Worthless Jelin now claimed it as his. The sword that should have been hers. She knew how her father would have reacted to her mother’s bartering the sword for shelter. She pinched her lips tight as she thought of Papa. Burk was not the kindest, gentlest father one could imagine. He was, in fact, very much as the king’s man had described a Forged man. He ate first and best at their meals and had always expected to be deferred to in all things. He was quick with a slap and slow to praise. In his early life, he’d been a warrior. If he needed something, he found a way to get it. She knew a tiny flame of hope. Perhaps, even Forged, he would still be her father. He might come home, well, back to the village where their home had stood. He might still rise before dawn to take their small boat out to …

Oh. The boat that now rested on the bottom, with only a handspan of its mast sticking up.

But she knew her father. He’d know how to raise it. He’d know how to build their house again. Perhaps there might be some return to her old life. Just her family, sitting beside their own fire in the evening. Their food on the table, their beds …

And he’d take back his sword, too.

The king’s man wasn’t having a great deal of luck persuading the village that their returning kin should be barred from the village, let alone murdered. She doubted he knew what he was about; surely if a mother remembered her child’s name and face, she would remember that she cared about that child! How could it be otherwise?

He soon saw he was not swaying them to his thinking. His voice dropped. “I will see to my horse and spend one night here. If you want help to fortify some of your homes or this shed, I’ll help with that. But if you will not ready yourselves, there is little I can do here. And yours is not the only village to be Forged. The king sent me to Shrike. Chance brought me here.”

Old Hallin spoke up. “We know how to take care of our own. If Keelin comes back, he’ll still be my son. Why wouldn’t I feed him and give him shelter?”

“Do you think I will kill my father because he behaves selfishly? You’re mad, man! If you are the sort of help King Shrewd sends us, we’re better off without it.”

“Blood is thicker than water!” someone shouted, and suddenly everyone seemed angry at the king’s messenger.

His face sank into deeper lines of weariness. “As you will,” he said in a lifeless voice.

“As we will indeed!” Carber shouted. “Did you think no one would look in the panniers on your mount! They’re full of loaves of bread! Yet seeing how devastated we are, you said nothing and made no offer to share! Who is heartless and selfish now, FitzChivalry Farseer?” Carber lifted his hands high and cried out to the crowd, “We ask King Shrewd to send us help, and he sends one man, and a bastard at that! He hoards bread that would ease our children’s bellies and tells us to slay our kin. This is not the help we sought!”

“I hope you touched none of it,” the man replied. His eyes, so earnest before, had gone distant and dark. “The bread is poisoned. It’s to use against the Forged in Shrike. To kill them and put an end to the murders and rapes there.”

Carber looked stunned. Then he shouted, “Get out! Leave our village now, tonight! We’ve had enough of you and your ‘help!’ Begone.”

The Farseer didn’t quail. He looked out over the gathered folk. Then he stepped down off the crate. “As you will.” He did not shout the word but his words carried. “If you will not help yourselves, there is nothing I can do here. I’ll be on my way. When I have finished my tasks at Shrike, I will come back this way. Perhaps by then, you will be ready to listen.”

“Not very likely,” Carber sneered at him.

The king’s envoy walked slowly to the door. His hand was not on his sword hilt, but the crowd flowed back to make way for him. Taura was one of those who followed him. His horse was still tethered outside. The lid of one pannier was loosened. The man paused to secure it. He patted the horse’s neck, untethered her, mounted, and rode off into the darkness without a backward glance. He left the way he had come and the sound of his mount’s hooves faded slowly.

In the morning, the rain continued and the day dragged by. None of the kidnapped folk returned. The red-hulled ship was no longer anchored at the edge of the bay. Jelin began to assert his authority over her family. Her mother helped with the cooking, and Gef salvaged wood that could be used to rebuild or as firewood. When Taura came in from standing her watches, Jelin commanded her to tend his brat so his wife Darda could rest. Cordel was a spoiled, snotty two-year-old who toddled about knocking things over and shrieking when he was reprimanded. His clothing was constantly soiled and they expected Taura to rinse out his dirtied napkins and hang them on the line above the fireplace to dry. As if anything could dry on the chill, damp days that followed the raid. When Taura complained, her mother would hastily remind her that some folk were sheltering under salvaged sails or sleeping on the dirt floors of the fish-smoking shed. She spoke low at such times, as if fearful that Jelin would overhear her complaints and turn them out. She told Taura that she should be grateful to help the household that had taken her in.

Taura did not feel grateful at all. It grated on her to see her mother cooking and cleaning like a servant in a house that was not theirs. Even worse was to see how Gef followed Jelin about, as anxious to please as a hound puppy. It was not as if Jelin treated him well. He ordered the boy about, teased and mocked him, and Gef laughed nervously at the taunts. Jelin worked the boy as if he were a donkey, and they both came home from trying to raise Jelin’s fishing boat soaked and weary. Gef didn’t complain; rather he fawned on Jelin for his attention. He had never behaved so with their father; her father had always been distant and gruff with both his son and daughter. Perhaps their own father had not been affectionate, but, simple or not, it was wrong for Gef to forget him so soon. Likely their father wasn’t even dead yet. Taura seethed in silence.

But worse came the next night. Her mother had made a fish stew, more like a soup for she had stretched it to feed all of them. It was thin and grey, made from small fish caught from shore, and the starchy roots of the brown lily that grew on the cliffs and kelp and small shellfish from the beach. It tasted like low tide smelled. They had to eat in shifts, for there were not enough bowls. Taura and her mother ate last, with Taura given a small serving and her mother scraping out the kettle for her dinner. As Taura slowly spooned up the thin broth and small pieces of fish and root, Jelin sat down heavily across from her. “Things have to change,” he said abruptly, and her mother gaped silently.

Taura gave him a flat look. He was staring at her, not her mother.

“It’s plain to see that there’s not enough in this house to go around. Not food, not beds, not room. So. Either we have to find a way to create more of those things or we have to ask some people to move out.”

Her mother was silent, gripping the edge of the table with both hands. Taura gave her a sideways glance. Her eyes were anxious, her mouth pinched tight as a drawstring poke. She’d get no help there. Her father taken less than five days ago and her mother already abandoning her. She met Jelin’s gaze and she was proud her voice didn’t shake as she said, “You’re talking about me.”

He nodded once. “It’s plain to see that caring for little Cordel doesn’t suit you. Or him. You stand your watches for the village, but that doesn’t put more food in the house or more firewood on the stack. You step over a chore that plainly needs doing, and what we ask you to do, you do grudgingly. You spend most of each day sulking by the fire.”

A coldness was running through her as he recounted her faults. It made her ears ring. Her mother’s silence was condemnation. Her brother stood away from the table, looking down, shamed for her. Frightened perhaps. They both felt Jelin was justified. They’d both surrendered their family loyalty to Jelin at the moment that they gave him her father’s sword. He was talking on and on, suggesting that she could go with some of the people who were scavenging the beaches at low tide for tiny shellfish. Or that she might walk for four hours to Shearton, to see if she would find work there, something she could do for a few coins a day to bring some food into the house. She made no reply to any of his words nor did she let her face change expression.

When he finally stopped talking, she spoke. “I thought our room and board here were well paid for in advance. Did not you take my father’s sword in its fine leather sheath, tooled with the words of my family’s motto? ‘Follow a Strong Man,’ it says! That’s a fine sword Buckkeep made. My father bore it in his days in King Shrewd’s guard when he was young and hearty. Now you have the sword that was to be my inheritance!”

“Taura!” her mother gasped, but it was a remonstrance for her, not a heart-stricken realization of what she had given away.

“Ungrateful bitch!” Jelin’s wife gasped as he demanded, “Can you eat a sword, you stupid child? Can it keep the rain from your back or warm your feet when the snow falls?”

Taura had just opened her mouth to reply when they heard the scream. It was not distant. Someone pelted past the cottage, shrieking breathlessly. Taura was first to her feet, opening the door to peer out into the rainy night as Jelin and Darda shouted, “Close the door and bar it!” As if they had learned nothing from the folk who had been burned to death when the raiders had torched their cottages.

“They’re coming!” someone shouted. “They’re coming from the beach, out of the sea! They’re coming!”

Her brother came crowding behind her to slip under her arm and peer out. “They’re coming!” he said in foolish approval. A moment later, the whistles sounded. Two blasts, over and over again.

“El’s balls, close that damn door!” Jelin roared. The sword he had so decried a moment before was bared in his hands now. The sight of it and the fine sheath discarded on the floor raised Taura’s fury to white-hot. She pushed past her brother, seized the edge of the door, and slammed it shut in his face. An instant later, she wished she had thought to take her cloak with her, but it was too fine of a defiant exit to spoil by going back for it.

It was raining, not heavily but in penetrating small insistent drops. Other folk were emerging from their homes, to peer out into the night. Some few had seized their pathetic weapons, cudgels and fish-knives and gaff hooks. Tools of trades that were never intended for battle or defense were all they had. A long scream rose and fell in the night.

Most folk stayed within their doorways, but some few, the bold or the hopeless, ventured out. In a loose group they walked through the dark streets toward the whistle. One of the men carried a lantern. It showed Taura damaged homes, some burned to cinders and others skeletons of blackened beams. She saw a dead dog that had not been cleared from the street. Perhaps his owner was no longer alive. Some homes stood relatively intact, light leaking from shuttered windows. She hated the smell the rain woke from the burned homes. Items that the raiders had claimed then dropped were scorched and sodden in the street. The scream was not repeated and to Taura that seemed more frightening than if it had gone on.

The lantern bearer held it high and by its uncertain light Taura saw several figures coming toward them. One of the men in the group suddenly called out “Hatilde! You live!” He ran toward a woman. She made no reply to his greeting. Instead, she abruptly stopped and stared at the rubble of a home. Slowly Taura and the others approached them. The man stood beside Hatilde, a questioning look on his face. Her hair was lank, her wet clothes hung limp on her. He spoke gently to her. “They burned your cottage. I’m so sorry, Hatilde.”

Without a word, she turned from him. The house next to her rubble had survived the attack. She walked to it and tried the door, and then pounded on it. An elderly woman opened it slowly. “Hatilde! You survived!” she exclaimed. A tentative smile began to form on her face.

But the Forged woman said nothing. She pushed the old woman out of her way and entered the cottage. The old woman stumbled after her. From within Taura heard her querulous cry of, “Please don’t eat that! It’s all I have for my grandson!”

Before Taura could wonder about that, a woman came running down the street toward them. She shrieked in terror as she passed two plodding silhouettes then, as she saw the huddled group, she sobbed out, “Help me! Help me! He raped me! My own brother raped me.”

“Oh, Dele!” a man in Taura’s group cried out, and doffed his cloak to offer it to cover her torn garments. She accepted it but shrank back from his touch.

“Roff? Is that you?” the lantern-bearer asked as a tall man strode out of the darkness toward them. The man was bare-chested and barefoot, his skin bright red with cold. He made no response but abruptly knocked a young man in the group to his knees. He tore the cloak from the youngster’s shoulders, half choking him in the process. He wrapped himself in it, glared at the gawkers, then turned and stalked toward a house.

“That’s not your house, Roff!” the lantern bearer cried as others helped the shaken lad to his feet. They huddled ever closer together, like sheep circled by wolves.

Roff did not pause. He tried the door and found it latched. He backed up two steps and then, with a roar, he charged the door and kicked it hard. It flew open. From within came angry shouts and a shriek. Taura stood openmouthed as Roff walked in. “Roff?” asked a man’s voice, and moments later, the sounds of a fight filled the night. Several of the men moved purposefully toward the door. A woman carrying a small child ran out toward them, crying, “Help, help! He’s killing my husband! Help.”

As two men ran in, Taura stood still in the darkened street. “This is what he meant,” she informed herself quietly. He’d been right. She’d thought the king’s man had been mad, but he’d been right.

Into the street stumbled Hatilde and the old woman. They were locked in fierce battle while a small child stood in the doorway and wailed his terror. Some folk sprang to separate them while others went to drag out Roff. In the midst of the shouting and the struggling fighters, Taura looked down the street and saw by the light of the open doorways more Forged ones coming. Folk opened their doors, peered out, and slammed them again. Dread and hope warred in her; would she see her father’s silhouette among them? But he was not there.

The youngster whose cloak Roff had stolen leaped onto his back when the other men dragged him out of the cottage. He wrapped an arm around Roff’s neck shouting, “I want my cloak back!” Another man tried to pull him off Roff while three others fought to detain Roff as someone shouted, “Roff! Give up, Roff! Let us help you! Roff! Stop fighting us.”

But he didn’t stop and while his opponents attempted only to restrain him, he struck out with full force, as pleased to kill them as to drive them off. Taura saw the moment when the other men lost all their restraint. Roff was borne to the ground under the weight of the other fighters. The one man pleaded for Roff to give up but the others were cursing and hitting and kicking Roff. But Roff kept fighting. A savage kick to his head ended it, and Taura cried out as she saw Roff’s neck snap and his ear touch his shoulder. Abruptly, he was still. Two more kicks from different men. Then, like rebuked dogs, they were suddenly, silently stepping back from his body.

In the street, the man who had first greeted Hatilde still gripped her from behind, pinning her arms to her side. The old woman was sitting up in the street, weeping and wailing. Hatilde was flinging her head back, her teeth snapping wildly and kicking her bare heels into the man’s legs. Taura had a flash of insight. The raiders had deliberately released them cold and hungry and soulless, so they would immediately have reasons to attack their families and neighbors. Was this why they had burned only half the village? Was it so that those who remained would know the fury of their own people?

But there was no quiet moment to mull over that thought.

“Sweet Eda!” A man shouted some distance away, and Roff’s friend cried out, “You’ve killed him! Roff! Roff! He’s dead! He’s dead!”

“Hatilde! Stop it! Stop it!”

But Roff was sprawled on the ground, his tongue thrust out of his bloody mouth, and Hatilde went on silently snapping, struggling and kicking. And in that moment of shocked unsilence, Taura heard the cries, the crashes, the shrieks and the furious roars from elsewhere in the village. Someone was blowing a whistle, desperately, over and over. Their folk had come back, Forged as King Shrewd’s messenger had warned them they would be. But now Taura knew what it meant. They would, indeed, take anything they wanted or needed. And some, like Roff, would not be stopped by anything short of death.

The villagers would kill her father. Taura abruptly knew that. Her father was a strong and stubborn man, the strongest man she’d ever known. He would not stop until he had what he needed. The only way to stop him from taking what he needed would be to kill him.

Papa.

Where would he be? Which way would he come? The whistles and shouts and screams were coming from every direction. The Forged were returning and it was worse than the night the raiders had come, setting fires and stealing and raping and killing. That attack had been a shock. But they had known their folk would return. Their dreads and hopes had risen, and fallen. And now, just when the villagers had begun to resume their lives, to rebuild houses and pull the boats ashore to repair them, the raiders struck again. With their own folk as weapons. With her father as their attacker.

Where would he be?

And she knew. He would go home.

Taura ran through the dark streets. Twice she dodged Forged ones. She knew them even in the dim light leaking from shuttered windows. They walked stiff and cold, as if puzzled at being thrust back into a life they had once shared. She ran past Jend Greenoak kneeling in the streets and sobbing, “But the baby? Where is our baby?”

Taura slowed her steps and stared unwillingly. Jend’s wife Salal stood in the street, her garments still dripping seawater, her arms empty of the babe she had carried off to the Red Ship. She stared at the burned rubble of their home. She spoke harshly. “I’m cold and hungry. The baby did nothing but cry. It was useless.” Her words carried no emotion, not regret nor anger. She stated her truth. Jend swayed where he knelt and she walked away from him, her arms embracing herself against the cold as she strode down the street toward a lit cottage. Taura knew what would come next.

But the woman who stepped out of the cottage held a cudgel and called over her shoulder, “Bar the door. Open for no one but me!”

Nor did the woman wait for Salal to try to enter. She strode forward to meet her, cudgel swinging. Salal did not retreat. Instead, she voiced her fury at being thwarted with an inhuman shriek and ran at the woman, her hands lifted to claw.

“NO!” shouted Jend, and found his feet to rush to his wife’s defense. So it would go, Taura suddenly knew. Some would stand with their loved ones, Forged or not, and others would defend their homes at any cost. Jend took a smashing blow to his gut and went down in the street but Salal fought on regardless of a dangling and crooked jaw. The defending woman was screaming wordlessly, turned just as savage as the Forged one she fought. The men who had fought Roff were standing and shouting at one another. Taura dashed past them, powered by both horror and fear. She did not want to see another person die tonight.

“Stand with your family,” her father had always told her. She remembered the day well. Someone had cursed Gef for dashing into the street, entranced by a flock of geese flying overhead.

“Keep your half-wit boy tethered to your porch!” the teamster had shouted at them. He’d had to rein in sharply and his slippery load of fresh fish had nearly slewed out of his cart. Papa had dragged him down from the seat of his cart and thrashed him in the street. No matter how her father might shun his simple son within the walls of his own home, in public he defended him. Her mother had echoed those words when her father came in with his bloodied knuckles and blackened eyes. “We always stand with our blood,” she’d told Taura. Then, Taura had not doubted that she meant it. Perhaps tonight, her mother would recall where her loyalties should be.

Taura was out of breath. She trotted rather than ran now, but her thoughts raced far ahead of her destination. She could well be on the path back to her old life. She would find her father and he would know her. She would warn him, protect him from villagers who might not understand. Even if he never showed affection for any of them again, he would still be Papa, and her family would be together again. She would rather sleep on cold earth with her family than sleep on the floor by the fire in Jelin’s house.

She ran past Jelin’s house and on, past the partially burned homes, away from the dim light that leaked from windows. This part of the village was dead; it stank of burned wood and burned flesh. She had lived in the same house all her life, but in all the destruction, she was suddenly not sure which burned wreckage had been their home. Thin moonlight reached down and glinted faintly only on wet wood and stone. She trotted through a foreign landscape, a place she had never been before. Everything she had ever known was gone.

She almost crashed into her father before she saw him. He was standing motionless, staring at where their house had been. She recoiled then stood still. He turned slowly toward her and for an instant the moonlight glinted in his eyes. Then darkness claimed his face again. He said nothing.

“Papa?” she said.

He didn’t respond.

The words vomited from her. “They burned the house. We saw them take you away. Your head was bloody. Mother told me to run and hide. She went to find Gef. I hid high in the old willow that overlooks the harbor. They took you out to their ship. What did they do to you? Did they hurt you?”

He was very still. Then he shook his head, a small quick shake as if a mosquito had buzzed in his ear. He walked past her toward the dimly lit part of the village that still stood. She hesitated then hurried after him. “Papa. The others in the village know you were taken. A man came from the king. He told the village to defend themselves against Forged ones. To kill them if we had to.”

Her father kept walking.

“Are you Forged, Papa? Did they do something to you?”

He kept walking.

“Papa, do you know me?”

His steps slowed. “You’re Taura. And you talk too much.” After he’d spoken he resumed his pace.

It was all she could do to keep from dancing after him. He knew her. He had always mocked and teased her that she was such a talker! His voice was flat, but he was cold and wet, hungry and tired. But he knew her. She hugged herself against the cold and hurried after him. “Papa, you have to listen to me. I’ve seen them killing some of the others who were kidnapped. We have to be careful. And you need a weapon. You need your sword.”

For five steps he kept his pace. Then he said, “I need my sword.”

“It’s at Jelin’s house. Mother and Gef and I have been staying there, sleeping on their floor. Mother gave him your sword, to let us stay with him. He said he might need it, to protect his wife and baby.” She had a stitch in her side from all the running, and despite hugging herself, the cold was seeping into her bones. Her mouth was dry. But she pushed all that to one side. Once Papa was inside the house, with his sword, he’d be safe. They’d all be safe again.

Her father turned toward the first lit house.

“No! Not there! They’ll try to kill you. First, we have to get your sword. Then you can get warm and have some food. Or a hot drink.” Now that she thought of it, there was probably no food left. But there would be tea and perhaps a bit of bread. Better than nothing, she told herself. He was walking on. She dashed ahead of him. “Follow me!” she told him.

A piercing scream rang out in the night, but it was distant, not nearby. She ignored it as she had ignored the angry shouts that came and went. She did not slacken her pace but walked backwards hastily, motioning for him to follow her. He came on doggedly.

They reached Jelin’s cottage. She ran up to the door and tried to open it. It was barred. She banged on it with her fists. “Let me in! Open the door!” she cried.

Inside, her mother lifted her voice. “Oh, thank Eda! It’s Taura: she’s come back. Please, Jelin, please let her in!”

A silence. Then she heard the bar lifted from its supports. She seized the handle and pulled the door open just as her father came up behind her. “Mother, I’ve found Papa! I’ve brought him home!” she cried.

Her mother stood in the door. She looked at Taura, then at her husband. A terrible hope lit in her eyes. “Burk?” her mother said, her voice cracking on his name.

“Papa!” Gef’s voice was both questioning and fearful.

Jelin pushed them both to one side. Papa’s sword was naked in his hand. He lifted it and pointed it at Papa. “Get back,” he said in a low and deadly voice. His gaze flickered to Taura. “You stupid little bitch. Get in here and get behind me.”

“No!” It wasn’t just that he’d called her a bitch. It was the way he held the blade unwavering toward her father. Jelin wasn’t even going to give him a chance. “Let us in! Let Papa in, let him get warm and have some food. That’s what he needs. It’s all that any of the Forged ones need, and I think if we give it to them, they’ll have no reason to hurt us.” At Jelin’s flat stare, she grew desperate. “Mother, tell him to let us both in. This is our chance to be a family again.”

The words tumbled from her mouth. She stepped, not quite in front of Papa, but closer to him, to show Jelin that he’d have to stab her before he could fight Papa. She wasn’t Forged. He had no excuse to stab her.

Papa spoke behind her. “That is my sword.” Anger rose in his voice on that last word.

“Get inside, Taura. Now.” Jelin shifted his stare to her father. He spoke sternly. “Burk, I’ve no wish to hurt you. Go away.”

Back inside the cottage, the baby started crying. Jelin’s wife began to sob. “Make him go away, Jelin. Drive him off. And her with him. She’s nothing but trouble. Oh, Sweet Eda, mercy on me and my child! Drive him away! Kill him!”

Darda’s voice was rising to hysteria and Taura could see in Jelin’s eyes that he was listening to her. Maybe he would stab her. Her voice rose to shrill despite herself. “Mother? Will you let him kill both of us? With Papa’s own sword?”

“Taura, get inside. Your father is not himself.” Her mother’s voice shook. She had hugged Gef to her side. He was sob panting, his prelude to one of his total panics. Soon he would race in circles, sobbing and shrieking.

“Mother, please!” Taura begged.

Then her father seized her by the back of her neck and her shirt collar. He flung her into the cottage. She collided with Jelin then fell at his feet. He was off balance and flailing when Papa reached in, past the tip of his own sword, to seize Jelin’s wrist. Taura knew that clamping grip. She’d seen him haul big halibut up off the bottom, his hands seized tight on the line. In a moment it happened as she knew it would. Jelin gave a cry and the sword fell from his nerveless hand. It was right next to her. She seized the hilt and scrabbled back into the room.

“Papa, I’ve got it! I’ve got your sword for you.”

Papa said nothing. He had not released his grip on Jelin’s wrist. Jelin was shouting and cursing and fighting Papa’s one hand, as if by breaking that grip he could win. Her father’s lips were pulled back from his set teeth. His eyes were empty. Jelin put all his efforts into pulling away. But Papa jerked the smaller man toward him. His free hand went to Jelin’s throat. He caught him there, his big hand right under Jelin’s jaw. He squeezed, and then abruptly released Jelin’s wrist and put both hands on his neck. He lifted Jelin up on his toes and Papa’s eyes were very intent, his mouth flat as he throttled the man. He tilted his head to one side and regarded Jelin’s darkening face with intent interest.

“No!” shrieked Darda, but she did nothing but retreat into the corner clutching her child. Gef seized two handfuls of his own hair and wailed loudly as he shook his own head. Taura’s mother was the one who charged in. She seized one of Papa’s thick arms and tugged at it. She hung her weight from it as if she swung from a tree branch.

“Burk! No, no, let him go! Burk, don’t kill him! He was kind to us, he gave us shelter! Burk! Stop!”

But Papa did not stop. Jelin’s eyes were wide, his mouth open. He had been clutching at Papa’s hands but now his hands fell away to hang limply at his sides as Papa shook him. Taura looked down at the sword in her hands. She lifted it in a two-handed grip, unsure of what she was going to do. She was shaking and the sword was heavy. She braced her feet and squared her shoulders and steadied the blade just as Papa dropped a floppy Jelin to the floor. He looked at his wife still clinging to his arm. He snapped his arm straight, flinging her aside, and she flew backwards.

And onto the sword.

Taura dropped the blade as her mother crashed into it. It stuck, sank, then fell away as her mother tumbled down. Papa took two steps forward and backhanded Gef. The blow drove him to the floor. “Quiet!” he roared at his idiot son. And for a wonder, Gef obeyed. Gef drew his knees tight to his chest and clapped both hands over his bleeding mouth as he looked up in terror at his father. The command almost silenced Darda as well. Jelin’s wife had one hand clapped over her own mouth and with the other she held Cordel tight to her body, muffling his cries.

“Food!” Papa commanded. He moved toward the fire and held out his hands to the warmth. Jelin did not move. Taura’s mother sat up, moaning and clutching her ribs. Taura looked down at the sword on the floor.

“Food!” her father said again. He glared round at them all, and his eyes made no distinction between his own bleeding wife and Jelin’s cowering one. Neither spoke nor stirred and Gef, as always, was useless.

Taura found her tongue. “Papa, please, sit down. I’ll see what I can find for you,” she told him, and went to Darda’s larder. The raiders had not burned Jelin’s home but had looted any foodstuffs they could find. She doubted she would find much on the shelves. In a wooden box, Taura found half a loaf of bread. That was all. But as she pulled the box down to get the bread, she saw something hidden behind the box. A clean cloth wrapped several sides of dry fish and a big wedge of cheese. Her outrage rose as she pushed it aside to see a trove of potatoes in a bag, a pot of honey, and a pot of rendered lard. Dried apples at the very back of the shelf. A braid of garlic! Darda had hidden all that rich food and forced them to exist on thin soup!

“You were holding the good food back from us!” she accused Darda, speaking toward the cupboard in a low voice. She broke a piece from the cheese and crammed it into her mouth. Behind her, her father roared, “NOW! I want food now!”

As Taura glanced over her shoulder, her father bared his teeth at her. His eyes were narrowed and he made a threatening noise in his throat. Taura carried the bread, honey, and cheese to the table. He didn’t wait for her to set it out nicely, but snatched the loaf in both his dirty hands. She dropped the cheese and set down the honey.

She backed away from the table. She spared a sideways glance for Darda and spoke in a low voice. “Mother, they were cheating us. Jelin said there wasn’t enough to go around but Darda hid food from us!”

Darda’s voice shook with fear and defiance. “It was our food before all this happened! We didn’t owe it to you! It was food for my boy; he needs it to grow! Jelin and I weren’t eating it! It was food for Cordel!”

Her father appeared to hear none of this. He had lifted the loaf to his mouth and was worrying a tremendous bite from it. Around that mouthful he yelled, “Drink! Something to drink. I am thirsty!”

Water was what there was, and Taura filled a mug with it and took it to him. Her mother had risen, staggered, then folded up to huddle by Gef. Her idiot brother was rocking back and forth. Instead of seeing to her own wound, her mother was trying to calm him. Taura took the cloth that had wrapped the loaf and went to her. “Let me see your wound,” she said as she crouched down beside her.

Her mother’s eyes flashed dark fire. “Get away from me!” she cried, and pushed Taura so she sprawled on the floor. But she did snatch up the cloth and hold it to her ribs. It reddened with blood, but only slightly. Taura guessed that the blade had sliced her but not deeply. She was still appalled.

“I’m sorry!” she said stiffly. “I didn’t mean to hurt you! I didn’t know what to do!”

“You did know. You just didn’t want to do it. As is ever your way!”

“Family first!” she cried out. “You and Papa always say that. Family first!”

“Does he look like he is thinking of his family?” her mother demanded. Taura looked over at her father. The cheese was almost gone. He had pushed a piece of bread into the pot of honey and was wiping it clean of sweetness. As she watched, he shoved it into his mouth. The discarded honeypot rolled to the edge of the table and fell to the floor with a crash.

Her mother levered herself to her feet, leaning on Gef’s shoulder. “Get up, boy,” she said quietly, tugging on him, and he rose. She took his hand and led him back to where Darda and Jelin’s son huddled. “Stay there,” she warned him, and he sank down on his haunches beside them. Clutching her side, she stood between them and her husband. Taura got slowly to her feet. She backed to the wall and looked from her father to her mother.

The fire crackled and Papa ate noisily, tearing at the bread with bared teeth. Rain and wind came in the open door. In the distance, people still shouted. Darda clutched her baby and sobbed into him and Gef made his babyish crooning in sympathy. Jelin was silent. Dead. Taura crept closer to the table. “Papa?” she said.

His eyes turned toward her then back to the bread. He tore off another mouthful.

“Family first, Papa? Isn’t that right? Shouldn’t we stay together, to fix our house and raise our boat?”

His gaze roved around the room and her hopes rose that he would speak. “More food.” That was his response. His eyes had a glitter in them she had never seen. As if they were shallow now, like puddles in the sun. Nothing behind them.

“There isn’t any,” she lied.

He narrowed his eyes at her and showed his teeth. Her breath caught in her throat. Papa crammed the last of the bread into his mouth. He stuffed the cheese in after it. He rocked from side to side in the chair as he chewed it then stood. She backed away from him. He picked up the mug, drank the last of the water and dropped it. “Papa?” Taura begged him.

He looked past her. He walked to the couple’s bed. He took Jelin’s extra shirt from its peg on the wall. He put it on. It was too small for him. Jelin’s wool cap fit him well. He peered around the cottage. Jelin’s winter cloak was on a hook beside the door. He took that, too. He swung it around his shoulders. Then he rounded to look at her accusingly.

“Please, Papa?” Could not he be who he had been, just for a time? Even if he cared nothing for them as the bastard had said, could not he be the man who always knew what they must do next to survive?

“More food?” He scratched his face, his blunt nails making a sound in his short beard. His gaze was flat.

That was all he said. He was thinking only of what he needed now. Nothing for what tomorrow might bring. Nothing for where he had been, what had happened to him, what had befallen the village. “You ate it all,” Taura lied quietly. She scarcely knew why she did so. Papa gave a grunt. He nudged at Jelin’s body and when he didn’t move, he stepped over it to stand in the open door. His head turned slowly from side to side. He took one step out the door and stopped.

His sword was still on the floor. Not far from it, the sheath lay as well. She heard her mother’s breathed prayer. “Sweet Eda, make him go away.”

He walked out into the night.

The other villagers would kill him. They would kill him and they would hate Taura forever because she hadn’t killed him. Because she’d let him kill Jelin. Darda would not be silent about that. She would tell everyone.

Taura looked over at her mother. She’d taken a heavy iron pan from the cooking shelf. She held it by the handle as if it were a weapon. Her eyes were flat as she stared at Taura. Yes. Even her mother would hate her.

Taura stooped to pick up the sword. It was still too heavy for her. The point of it dragged on the floor as she reached for the sheath. “Follow a Strong Man” the carved lettering told her.

She shook her head. She knew what she should do. She should close the door behind Papa and bar it. She should say she was sorry a hundred, a thousand times. She should bind Mother’s wound and help Darda compose her husband’s body. She should take Papa’s sword and stand in the door and guard them all. She was the last person they had who might stand between them and the Forged ones roaming the streets.

She knew what she should do.

But her mother was right about her.

Taura looked back at them all, then took Darda’s cloak from the hook. She put it on and pulled the thick wool hood up over her damp hair. She heaved the sword up so it rested on her shoulder like a shovel. She stooped and took up the fine sheath in her free hand.

“What are you doing?” her mother demanded in outrage.

Taura held out the sheath toward her. “Following a strong man,” she said.

She stepped out into the wind and rain. She kicked the door shut behind her. A moment longer she stood in the scant shelter of the eaves. She heard the bar slammed down into the supports on the door. Almost immediately, Darda began shrieking, anger and grief in furious words.

Taura stepped out into the night. Her father had not gone far. His hunched shoulders and stalking stride reminded her of a prowling bear as he moved through the rain toward his prey. A decision came to her. She pushed the empty sheath through her belt and gripped the sword’s hilt in both hands. She considered it. If she killed him, would her mother forgive her? Would Darda?

Not likely.

She ran after him, the bared sword heavy and jouncing with every step she took. “Papa! Wait! You’ll need your sword!” she called after him. He glanced back at her but said nothing as he halted. But he waited for her. When she caught up with him, he walked on.

She followed him into the darkness.