Читать книгу The Book of Swords - Gardner Dozois, Гарднер Дозуа, Gardner Dozois - Страница 7

INTRODUCTION BY GARDNER DOZOIS

ОглавлениеOne day in 1963, I stopped in a drugstore on the way home from high school (at that point in time, spinner racks full of mass-market paperbacks in drugstores were one of the few places in our town where books were available; there was no actual bookstore), and spotted on the rack an anthology called The Unknown, edited by D. R. Bensen. I picked it up, bought it, and was immediately enthralled by it; it was the first anthology I ever bought, and a purchase that would have a long-term effect on my future career although I didn’t know that at the time. What it was was a collection of stories that Bensen had culled from the legendary (if short-lived) fantasy magazine Unknown, edited by equally legendary editor John W. Campbell, Jr., who at about the same time as he was revolutionizing science fiction as the editor of Astounding was revolutionizing fantasy in the pages of Astounding’s sister magazine Unknown from 1939 to 1943, when the magazine was killed by wartime paper shortages. In the early sixties, in a decade when the publishing industry was still coming out from under the shadow of postwar grim social realism, there was very little fantasy being published in a format affordable to purchase by a short-of-funds high-school student (except for the stories in genre magazines such as The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, which I didn’t know about at the time), and the rich harvest of different types of fantasy story available in Unknown was a revelation to me.

The story that had the biggest effect on me, though, was a bizarre, richly atmospheric story called “The Bleak Shore,” by Fritz Leiber, in which two seemingly mismatched adventurers, a giant swordsman from the icy North named Fafhrd and a sly, clever, nimble little man from the Southern climes called the Gray Mouser, are compelled to go on a doomed mission which seems destined to send them to their death (which fate, however, they cleverly avoid). It was a story unlike anything I’d ever read before, and I immediately wanted to read more stories like that.

Fortunately, it wasn’t long before I discovered another anthology on the drugstore spinner racks, Swords & Sorcery, edited by L. Sprague de Camp, this one not only containing another Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser story, but dedicated entirely to the same kind of fantasy story, which I learned was called “Sword & Sorcery,” a name for the subgenre coined by Leiber himself; in the pages of this anthology, I read for the first time one of the adventures of Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian and C. L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry, as well as stories by Poul Anderson, Lord Dunsany, Clark Ashton Smith, and others. And I was hooked, becoming a lifelong fan of Sword & Sorcery, soon haunting used-book stores in what was then Scollay Square in Boston (now buried under the grim mass of Government Center), hunting through piles of moldering old pulp magazines for back issues of Unknown and Weird Tales that featured stories of Conan the Barbarian and Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser and other swashbuckling heroes.

What I had blundered into was the first great revival of interest in Sword & Sorcery, a subgenre of fantasy that had at that point lain fallow for decades, with almost all of the material in those anthologies and those old pulp magazines having been published in the thirties or forties or even earlier, about the time that stories that took place in distinct fantasy worlds instead of seventeenth-century France or imaginary Central European countries began to precipitate out from the larger and older body of work about swashbuckling, sword-swinging adventurers written by authors such as Alexandre Dumas, Rafael Sabatini, Talbot Mundy, and Harold Lamb. After Edgar Rice Burroughs in A Princess of Mars and its many sequels sent adventurer John Carter to his own version of Mars, called Barsoom, to rescue princesses and have sword fights with giant four-armed Tharks, a closely parallel form to Sword & Sorcery sometimes called “Planetary Romance” or “Sword & Planet” stories developed, most prominently in the pages of pulp magazine Planet Stories between 1939 and 1955, with the two subgenres exchanging influences, and even many of the same authors, including authors such as C. L. Moore and Leigh Brackett, who were highly influential in both forms. The richly colored tales that made up Jack Vance’s classic The Dying Earth, also published about then, were also technically science fiction, but with their interdimensional intrusions, strange creatures, and mages who wielded what could either be looked at as magic or the highest of high technology, they could also function as fantasy as well.

Probably not coincidentally, interest in Sword & Sorcery, which had faded over the wartime years and throughout the fifties, began to revive in the sixties, after the Mariner and Venera and other space probes were making it increasingly obvious that the rest of the solar system was incapable of supporting life as we knew it—no ferocious warriors to have sword fights with or beautiful princesses in diaphanous gowns to romance. Nothing but airless balls of barren rock.

From now on, if you wanted to tell those kinds of stories, you were going to have to do it in fantasy.

Throughout the early sixties, Sword & Sorcery boomed, with D. R. Bensen, L. Sprague de Camp, and Leo Margulies mining the rich lodes of Unknown and Weird Tales magazines for other anthologies (Bensen—an important figure in the development of modern fantasy, now, sadly, mostly forgotten—was the editor of Pyramid Books, and also mined the pages of Unknown for classic fantasy novels such as de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s The Incomplete Enchanter and The Castle of Iron to reprint), collections of the original Conan stories being reissued, new Conan stories and novels being produced by other hands, Michael Moorcock producing his hugely popular stories and novels about Elric of Melniboné (which have continued to the present day), and obvious imitations of Conan such as John Jakes’s “Brak the Barbarian” stories being turned out. (At about this time, Cele Goldsmith, the editor of Amazing and Fantastic magazines, began to coax Fritz Leiber out of semiretirement and got him to write new Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories for Fantastic, which, once I noticed that, induced me to begin regularly picking a genre magazine up off the newsstands for the first time, which in turn induced me to begin buying science-fiction magazines such as Amazing, Galaxy, and Worlds of If—which means that, ironically, although I’d later become associated with science fiction, and would edit a science-fiction magazine myself, I came to them first because I was looking for more Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories in the pages of a fantasy magazine … although to be fair I was at the same time reading SF such as the Robert A. Heinlein and Andre Norton “juveniles,” and stuff such as Hal Clement’s Cycle of Fire and—also published by Pyramid Books—Mission of Gravity.)

Then came J.R.R. Tolkien.

J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy is often cited these days as having single-handedly created the modern fantasy genre, but, while it is certainly hard to overestimate Tolkien’s influence—almost every subsequent fantasist was hugely influenced by Tolkien, even, haplessly, those who didn’t like him and reacted against him—what is sometimes forgotten these days is that Don Wollheim published the infamous “pirated” edition of The Fellowship of the Ring (the opening book of the trilogy) as an Ace paperback in the first place because he was casting desperately around for something—anything!—with which to feed the hunger of the swelling audience for Sword & Sorcery. The cover art of the Ace edition of The Fellowship of the Ring (by Jack Gaughn, of a wizard waving a sword and a staff aloft on top of a mountain) makes it clear that Wollheim thought of it as a “sword & sorcery” book, and his signed interior copy makes that explicit by touting the Tolkien volume as “a book of sword-and-sorcery that anyone can read with delight and pleasure.” In other words, in the United States at least, the genre audience for fantasy definitely predated Tolkien, rather than being created by him, as the modern myth would have it. Don Wollheim knew very well that there was a genre fantasy audience already out there, already in place, a hungry audience waiting to be fed—although I doubt if even he had the remotest idea just how tremendous a response there would be to the tidbit of “sword & sorcery” that he was about to feed them. The Tolkien novels had already appeared in expensive hardcover editions in Britain, but the Ace paperback editions—and the “authorized” paperback editions that followed from Ballantine Books—made them available for the first time in editions that kids like me and millions of others could afford to buy.

After Tolkien, everything changed. The audience for genre fantasy may have already existed, but there can be no doubt that Tolkien widened it tremendously. The immense commercial success of Tolkien’s work also opened the eyes of other publishers to the fact that there was an intense hunger for fantasy in the reading audience—and they too began looking around for something to feed that hunger. On the strength of Tolkien’s success, Lin Carter was able to create the first mass-market paperback fantasy line, the Ballantine Adult Fantasy line, which brought back into print long-forgotten and long-unavailable works by writers such as Clark Ashton Smith, E. R. Eddison, James Branch Cabell, Mervyn Peake, and Lord Dunsany. A few years later, Lester del Rey took over from Lin Carter and began to search for more commercial, less high-toned stuff that would appeal more directly to an audience still hungry for something as much like Tolkien as possible. In 1974, he brought out Terry Brooks’s The Sword of Shannara, and although it was dismissed by many critics as a clumsy retread of Tolkien, it proved hugely successful commercially, as did its many sequels. In 1977, Del Rey also scored big with Lord Foul’s Bane, the beginning of the somewhat quirkier and less derivative trilogy, The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever, by Stephen R. Donaldson, and its many sequels.

Oddly, as fantasy books began to sell better by far than ever before, interest in Sword & Sorcery began to fade. Sword & Sorcery had always been a subgenre mostly driven by short fiction, but, inspired by Tolkien, the new fantasy novels began to get longer and longer and spawn more and more sequels, and now began to be largely thought of as a distinct subgenre, “Epic Fantasy.” It’s sometimes difficult for me to make a distinction between Epic Fantasy and Sword & Sorcery—both are set in invented fantasy worlds, both have thieves and sword-wielding adventurers, both take place in worlds in which magic exists and there are sorcerers of greater or lesser potency, both feature fantasy creatures such as dragons and giants and monsters—although some critics say they can distinguish one from the other by criteria other than length. Be that as it may, as books thought of as Epic Fantasy became more and more prominent, people talked less about Sword & Sorcery. It never disappeared entirely—Lin Carter edited five volumes of the Flashing Swords! anthology series between 1971 and 1981, Andrew J. Offutt, Jr. edited five volumes of the Swords Against Darkness anthology series between 1977 and 1979, Robert Lynn Asprin started the long-running series of Thieves’ World shared-world anthologies in 1978, Robert Jordan produced a long sequence of Conan novels throughout the eighties before turning to his multivolume Wheel of Time Epic Fantasy series, Glen Cook produced recognizable Sword and Sorcery work (notably his tales about the Black Company) throughout the same period, as did C. J. Cherryh, Robin Hobb, Fred Saberhagen, Tanith Lee, Karl Edward Wagner, and others; Marion Zimmer Bradley edited a long sequence of Sword and Sorceress anthologies, with the emphasis on female adventurers, throughout the seventies, and Jessica Amanda Salmonson produced a similarly female-oriented set of anthologies, Amazons and Amazons II, in 1979 and 1982 respectively.

Nevertheless, as the eighties progressed into the nineties, Sword & Sorcery continued to fade as a subgenre, until it was rarely ever mentioned and was in danger of being altogether forgotten.

Then, at the end of the nineties, things began to turn around.

Why they did is difficult to pinpoint. Perhaps it was the enormous commercial success of George R.R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones, published in 1996, and its sequels, which influenced newer writers by showing them a grittier, more realistic, harder-edged kind of Epic Fantasy, one with characters who were often so morally ambiguous that it was impossible to tell the good guys from the bad guys. Perhaps it was just time for a new generation of writers, who had been influenced by the classic work of writers like Leiber and Howard and Moorcock, to take the stage and produce their own new variations on the form.

Whatever the reason, the ice began to thaw. Soon people began to talk about “The New Sword and Sorcery,” and in the last few years of the twentieth century and the early years of the twenty-first century, there were writers such as Joe Abercrombie, K. J. Parker, Scott Lynch, Elizabeth Bear, Steven Erikson, Garth Nix, Patrick Rothfuss, Kate Elliott, Daniel Abraham, Brandon Sanderson, and James Enge making names for themselves, there were new markets in addition to existing ones such as F&SF for Sword & Sorcery, such as the online magazine Beneath Ceaseless Skies and print magazine Black Gate, and new anthologies began to appear, such as my own Modern Classics of Fantasy in 1997, which featured classic Sword & Sorcery stories by Fritz Leiber and Jack Vance, The Sword & Sorcery Anthology, edited by David G. Hartwell and Jacob Weisman, a retrospective of some of the best old stories of the form, and Epic: Legends of Fantasy, edited by John Joseph Adams, an anthology reprinting newer work by newer authors. Most importantly, new short work began to appear, collected in anthologies such as Legends and Legends II, edited by Robert Silverberg, and later in Fast Ships, Black Sails, edited by Ann VanderMeer and Jeff VanderMeer, and Swords & Dark Magic: The New Sword and Sorcery, edited by Jonathan Strahan and Lou Anders, the first dedicated anthology of the New Sword and Sorcery.

All at once, we were in the middle of another great revival of interest in Sword & Sorcery, one which has so far not faded again as we progress deeper into the second decade of the twenty-first century. Already there’s another generation of newer writers such as Ken Liu, Rich Larson, Carrie Vaughn, Aliette de Bodard, Lavie Tidhar, and others, taking up the challenges of the form, and sometimes evolving it in unexpected directions—and behind them are yet more new generations.

So, call it Sword & Sorcery, or call it Epic Fantasy, it looks like this kind of story is going to be around for a while for us to enjoy.

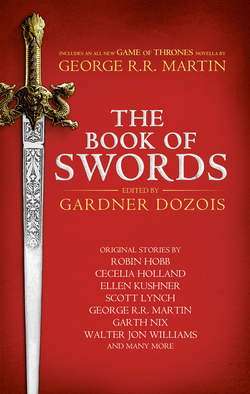

I’ve edited other anthologies with new Sword & Sorcery stories in them, such as the Jack Vance tribute anthology Songs of the Dying Earth, Warriors, Dangerous Women, and Rogues (all edited with that other big-time Sword & Sorcery fan, George R.R. Martin), but I’ve always wanted to edit an anthology of nothing but such stories, which is what I’ve done here with The Book of Swords, bringing you the best work of some of the best writers working in the form today, from across several different literary generations.

I hope that you enjoy it. And it’s my hope that to some young kid out there, it will prove as enthralling and inspirational as Unknown and Swords & Sorcery did to me back in 1963—and so a new Sword & Sorcery fan will be born, to carry the love of this kind of swashbuckling fantasy tale on into the distant future.