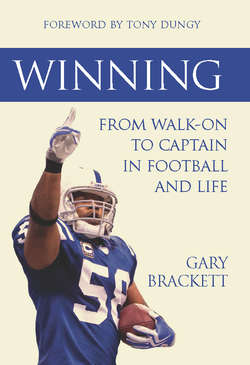

Читать книгу Winning: From Walk-On to Captain, in Football and Life - Gary Brackett - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеThe picture I looked at first has been the source of countless jokes over the years. It depicts all of my immediate family gathered together at our house. For some reason, we are sporting nametags. Perhaps this was a neighborhood function or family reunion. Though the exact memory has faded, the feeling of those days remains. I look at the picture and can almost hear the sounds, can feel the warmth of the day, not quite hot, but warm.

Our mother had arranged us in descending order from oldest to youngest. Granville stands on the far left and is bored and uninterested in the photographer. To his left stands Greg. He has worn a striped tank top identical to Granville’s. I don’t view this imitation with negative judgment. The younger brothers all admired and copied the older ones. Nothing wrong with being a copycat as long as you’re copying the right cat! Apparently, Grant and I had decided it was too warm for full shirts, even tank tops, and instead we chose for the day our standard ’80s half shirt. Behind us, tucked under our father’s big legs, huddled the youngest, and our only sister, Gwendolyn.

We kids were uninterested in the task at hand, and a close look at the photo reveals less about our personalities than our boredom. But if you look closely at my parents, you can tell certain things about their life and times. Mom had a rather unfortunate Jheri curl. She smiles slightly, the smile of someone who understands the difficulties of daily living, yet is happy to have her family around her. Her stance is revealing. She does not stand haughty or proud, but solid. She was in many ways our rock. Dad’s gestures are just as telling. He is shouting in the direction of someone outside the frame. His head is arched back and in one hand he is holding a frosty mug, just emptied, not yet filled with a new beer. Perhaps the most noticeable thing about him is his size. He is broad shouldered and tall. He looks fit. He does not stand like someone who should be trifled with. And that was him. A former Marine, he took life seriously and always demanded that we be places punctually. At the same time, he also wasn’t afraid to cut loose a bit with a drink or two.

The photo was taken in Glassboro, New Jersey, where we had just moved from Camden. For those who are unfamiliar with the statistics of crime throughout the country, Camden often takes the dubious prize of Most Dangerous City in America. This statistic is based on numbers compiled by the FBI regarding the number of violent crimes per person. Some of Camden’s citizens wear this ranking with pride, with T-shirts that say on the front # 1 in America (and on the back) America’s Worst City.

Situated just across the river from of the City of Brotherly Love, Philadelphia, many parts of Camden, New Jersey, are noticeably unbrotherly. Perhaps many of the problems are the result of poverty. Two out of five citizens live below the poverty line, and the school system was recently taken over by the state of New Jersey due to student drop-out rates.

Behind us in the photo sits our new home. With four bedrooms and two bathrooms, it was a great improvement over our previous living situation. If the first photo on my computer had been of our home in Camden, it would have pictured a row home with three bedrooms and a bathroom that was perpetually broken. Many houses on our row, these were the row houses you hear frequently about in discussions of American crime, were boarded up. Other neighboring houses in Camden suggested a complete lack of civic pride, or perhaps just patchwork ingenuity. From the wide array of building materials, it was clear that when something broke, whatever was cheapest would serve as a replacement. This fix-it fast, fix-it cheap approach created a hodgepodge of architecture. Brick portions of the house ran straight into faux brick shingle material, as if the builder ran out of money mid-way through construction and chose instead a less costly option. Cheap siding of multiple types, asbestos shingles, rotting wood, and even portions of tin, “decorated” the fronts of houses and lent a confused look that bespoke poverty. Paint schemes on houses had only one common characteristic—a complete lack of schematic planning and years of age and disuse. The exceptions to the rule, folks bravely holding on to their pride and often defending their homes forcefully, were stuck next to neighbors that neither cared about nor were capable of maintaining appearances. When you account for all the citizens of Camden addicted to drugs of various degrees of illegality, you understand how and why the street came to look the way it did.

The backyard of our Camden house was about the size of a standard jail cell and had a comparable lack of comfort. No lawn, no bushes, just a ten-foot-by-ten-foot section of concrete, just enough room for a picnic table. To many people this lack of a backyard might be a good thing—no grass to cut. But with four boys, it was my mother’s nightmare. The lack of space left us with only one option. We had to take our games out into the street up front, dodging cars and drug dealers as we caught passes and ran routes. The most astounding thing to me now is that on that broken and pothole-riddled asphalt, we played tackle. In Camden, toughness developed at a young age. I still have a scar from tackling Greg in the street and catching a piece of glass in my leg. When I finally dragged him down, blood streamed from my knee, tears welled up in the corners of my eyes. Greg carried me inside to get me cleaned up. Even as he sympathetically helped me bandage the wound, he looked at me with stern eyes and said in a clear voice, “You gonna have to be tougher around here to make it, Gary. You can’t go crying about little stuff like this. I know it hurts, but even when you don’t think you can bear it…you can. Just reach down for something extra.”

This combination was normal for my brother Greg. He was always caring but firm with me. He had my back, but also insisted that I learn to take up for myself. He helped teach me that valuable lesson about the size of the dog in the fight mattering much less than the size of the fight in the dog. This dog developed particular toughness from playing against older kids early in life, and from words like these from my brothers. I knew as the smallest kid out there that I had to make up for what I lacked somehow. Nobody felt sorry for me, so I had better not feel sorry for myself. This all helped me in the long run. No one gets better from playing against weaker competition. Challenge and adversity stir growth!

One episode is seared into my mind. My brothers and I were out in front of our house in the street. We were playing a game of some sort with neighborhood guys, and for some reason Granville ended up in a tussle with two neighborhood thugs. Without thinking, every one of the Brackett brothers jumped on those poor guys. They ran off knowing that when you messed with one of us, you had better expect us all to join, even little me at five years old.

Granville got into another fight that was even more dangerous. On this day I was near the front door when the altercation broke out. I copied what I had seen on TV, went inside and grabbed one of my father’s handguns and came out of the house shouting. I had no intention of shooting anything, but that did nothing to soften the whipping I got when Dad got home and heard the story.

“This thing is not a toy, Gary! You have no idea the kind of pain you can cause with this gun.”

“But, Dad, I wasn’t going to use it.”

“One thing I always say about guns, Gary, is never get one out and point it at something unless you are prepared to go all the way.”

When I was five, my parents decided to move the family to Glassboro, a safer area with more space, and where perhaps we would do a better job of staying out of trouble. Camden’s streets were just too dangerous. Our new home was only about twenty minutes away so my older siblings weren’t going too far from their friends. But it was some distance into the suburbs and away from the big city of Philly next door. We all helped pack, and as we prepared for the big day I grew nervous and lashed out.

“Mom, what our new house be like?”

“You’ll like it, Gary. We’ll have more of a yard to play in.”

“Yeah, but what about my old room? What about my friends?”

“You will have an even bigger room, and across the street you and your brothers will be able to make forts!”

“Mom, I don’t want to go!”

“Gary, you remember what I always tell you now: don’t fear and don’t be angry. One minute of anger robs you of sixty seconds of happiness.”

As a young kid I had no reason to doubt my mom. She never led me wrong. But I had heard her and dad whispering late at night about the move. They knew it needed to happen, but moving five kids even a short distance is a chore.

In Glassboro, things were definitely better. The schools were friendlier places with fewer students and nicer teachers. Our new house had more room, another bedroom and bathroom to be exact. We thought we had gone to heaven. There was more than one bathroom, and both of them were functional. Even more exciting than the new space inside the house was the new space outside. No more playing in the street and getting glass in our knees. We now had a yard!

The front of the house emptied out into the projects. We lived right across from a federal government housing development, each of the little brick houses was essentially the same design. But in between those projects and our house grew grass. And our backyard stretched back perhaps a half football field into some woods. The side yard extended for about fifty yards before it sloped gently into a drainage ditch. We played football and baseball year-round. And here is the best part of growing up with four boys in a house: no need to recruit because you always have numbers for a game of two on two. We Bracketts had enough to field a game with just the brothers. Since I was the youngest, and Greg was the second oldest, we often ended up playing against Granville and Grant. Greg and I developed our own secret language for plays, used hand signals our brothers never could decipher, and were usually encouraging teammates.

This neighborhood was a more family-friendly place. Sometimes at night we would play late, and Dad would come outside and whistle. That whistle covered the whole projects, and reached clearly to the basketball courts where we so often spent our time. If we didn’t hear it, others did. Those who lived around us knew two things: if that whistle sounded, Granville Brackett expected his boys home. And he didn’t expect them sooner or later, he expected them to be there quick! Not now, but RIGHT now. So, that whistle was our family version of: “ThunderCats ThunderCats ThunderCats Ho!” At that sound, we dropped what we were doing, ended whatever game we were playing, and moved.

If we weren’t playing sports, we went around gathering up cardboard from curbs and dumpsters, using it to construct forts in the vacant lot across from our house. In these forts we pretended we were trapped in a forest and surrounded on all sides by enemies. We envisioned ourselves in foreign lands. But when it rained, we were right back in New Jersey and faced a problem our neighbors here in Glassboro struggled with: we were evicted. Was everything perfect in Glassboro? Not by a long shot. But things were better than Camden. And after all, we are always involved in accepting our own perceptions and realities. Sometimes we had to sell ourselves on the idea of our own life. Even though we knew it might rain, we still built the forts. And while those protective cardboard homes were still standing, we had some fun in them. Often, we must make and shape our own reality.

Ever since I can remember, I knew without a doubt that I wanted my reality to involve football. When I told people this around middle school they surely thought: who doesn’t? My attraction to the sport was borne out of a particular experience. In the seventh grade, the one and only Reggie White came to visit our school. He played for the beloved Philadelphia Eagles and was my favorite player. The day of his visit, the place buzzed with excitement.

“Reggie White is gonna be here.”

“Gary, you think he’ll sign autographs?”

“I don’t care about autographs. I just want to see how big he is!”

When Reggie spoke in the auditorium, he talked about why other players and coaches referred to him as “the minister of defense.” He talked about dreaming big and reaching for the clouds, because even if you miss you’ll be among the stars. When we kids looked up at Reggie, we thought that he probably didn’t have to reach too far for those stars. He was absolutely massive! But after hearing that speech I dreamed big. Our class talked about it afterwards and the teacher asked, “Gary, what do you want to do with your life?”

“I want to play in the NFL.”

The teacher grimaced subtly, “What else might you want to do?”

I did not budge or offer an alternative, but I also did not say what I thought next. I thought it might be disrespectful and get me in trouble. My mind burned with a singular thought: I will play in the NFL some day.

Too often in today’s world kids don’t know or care what they want to do with their lives. When I ask children today the questions my teacher posed to me, the kids who say “nothing” really scare me. Those kids will be the ones who get exactly what they planned for: Nothing! After all, people don’t usually plan to fail, but too often they fail to plan. No one wants to live check to check for most of his or her life. But many people do. In my opinion, your perspective on life often determines the amount of success you have in it. From early on, I set goals and worked methodically to achieve them. Sure there were roadblocks along the way and points where I strayed from the path, but I never forgot the path I was seeking and always hustled back to it.

I was taught these values, in large part, through the examples set for me by older brothers. As I started playing more sports, my reality began to revolve increasingly around my brothers Granville, Greg, and Grant. Each of them was athletically talented. Each played three sports in high school. Granville, the oldest, probably looked at us, his younger brothers, with a bit of annoyance. After all, his primary perception of us was as kids he had to baby-sit. Grant was closest to my own age, and so we were on many teams together. We had a unique bond due to this proximity in years. Like many siblings close in age, we competed against each other more than the others.

I looked up to Greg in particular because he played football. He was the stud running back who scored all the touchdowns. When he played defense, he made all the tackles. He was the kid others in high school wanted to be. He was magnetic. Every moment I spent with him, I felt like I was being given a gift. He was a popular kid, a bit more outgoing than the other brothers. We were all captains of our teams, but he was one of the guys who the coaches picked to captain as soon as they could. He had a powerful leadership quality. I remember asking him one day about how he got to be captain.

“Don’t lead by talking Gary. Words are meaningless without action. Knowledge doesn’t matter nearly as much as people say either. What are you going to do with information? You have to act on it! That’s what matters.”

Greg lived by those words. He was always the first one in the weight room at practice, pushed others in sprints, and volunteered for the toughest match-ups in basketball. He didn’t just talk the talk. He walked the walk in such a way that people wanted to follow him.

“Yo G Baby what you lookin’ at?”

My boy Cato brought me back to the present, “Just these old photos. Heading down to this big event, and thinking about some of the folks that got me to this point.”

“Yeah, it’s wild the folks who helped us get here.”

“Man, thinking about my brother Greg. He basically taught me how to play football.”

Cato teased me, “I thought you were a man…self-made!”

• • • • •

“Nah, nah, I ain’t self-made. To say that would be a lie and would disrespect everyone who helped get me to this seat on the plane. Without them, there is no way I’d be here. Sometimes you have to believe in someone else’s belief in you before your own belief kicks in.”