Читать книгу Winning: From Walk-On to Captain, in Football and Life - Gary Brackett - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

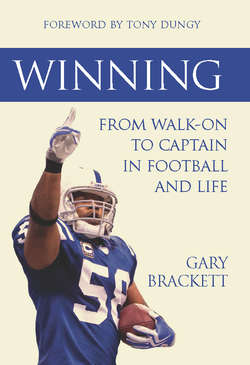

FOREWORD BY TONY DUNGY

ОглавлениеWhen I first got into coaching, Chuck Noll was my boss. He would tell me before I went on scouting trips, “Don’t go to the weighing and measuring sessions. And don’t take your stopwatch. Just watch the games, and then the films, and see who’s making the plays. Those are the guys we want to have on our team.”

Gary Brackett is one of those guys you always want on your team. But if I had carried a certain standard for an Indianapolis Colts player in terms of height, weight, speed, especially as a middle linebacker, he wouldn’t have made it. If you were in a grocery store or at the zoo, you wouldn’t walk by Gary Brackett and think, “That guy is the middle linebacker for an NFL team.” So to do what he has done is both physically and mentally incredible. He’s so competitive and so smart that when those qualities are coupled with his desire to play and win, you, as the coach, want him on the field at game time.

Much has been made of Gary being undrafted by the Colts and becoming, in time, our defensive captain. Sometimes fans think it’s harder for coaches to keep a free-agent rookie like Gary over someone they drafted. Actually, it isn’t hard at all to keep the players who shine in training camp if your commitment is to be fair to the team and build your success around those who will give you their utmost, and their utmost fits the needs of the team. I always prayed that I didn’t let personal feelings sway me when making final decisions. We needed to be objective and fair, to keep those guys who are best for the team.

Gary is one of those guys who wins for you. You’re going to get a lot done with people like Gary, a guy who makes the players around him perform better. On good teams, those players stand out and get an opportunity because the organization is committed to do what’s best overall. For a coach, it’s very rewarding to see something special in a player, to believe there’s something unique about him, and to know you have the support of everyone associated with the team to choose him regardless of who might have been drafted over him—then to see that person rise to a leadership role on and off the field.

The intangibles that Gary brings to the game make him a standout player—his perseverance and toughness and discipline and commitment to be the best. Yes, he’s the exception to the rule…and it’s true, you can go broke looking for the exceptions. Gary wouldn’t say this, but it’s very hard to play in the NFL at his size. Sometimes when you see a picture of him in the huddle, surrounded by all those huge defensive guys, you almost can’t believe it. And he’s the leader of that group! As captain, he’s the individual who all those bigger guys look to and follow. That’s when you realize it’s the personal qualities that an individual brings to the game that will help your team the most.

What made the biggest impression upon me, right from the start, was Gary’s desire. When we first talked to him, he told me about growing up in New Jersey and wanting to play for his home state school, Rutgers, even if they couldn’t give him a scholarship. That was a big deal to him; he committed to do whatever it took to make that team. That sort of desire is what separates the almost-make-it players from the truly great ones.

Gary’s not an extrovert, and he’s certainly not the first guy you’d notice in terms of who’s talking. But he plays, and lives, with a lot of emotion. Emotion is a key quality you look for in a player, and even moreso, a leader.

I’ve always believed that a captain should be elected instead of appointed. By electing someone to be your captain, it signals that this individual was selected by the team to represent the team, so we always voted. Captains were not just a title. David Thornton had been our defensive captain. When he went to Tennessee, I wasn’t sure who the team was going to chose to replace him. There were a lot of very good players on that defensive team. Also, Gary hadn’t been there for very long and had only been a starter for a year.

Surprisingly, the vote was a landslide. I took this to mean that the team recognized a lot of the same things in Gary that the other coaches and I saw in him. To get 90 percent of the votes meant that as a group, the team knew who they wanted to represent them, as well as recognizing his toughness and ability to handle pressure.

Your captains do a great deal more than most fans think. As the coach, my job was to deliver a winner, but you need everyone to buy into the program. Gary and Peyton Manning did such a great job for us, reinforcing the message that the coaches delivered in the locker room and putting it into action on the field. Captains also serve as representatives of the players off the field. I say that my door is always open, but there are a lot of players, especially the young guys, who don’t feel comfortable coming into my office. With Gary as their captain, they knew they had someone they could talk to who would carry their message forward.

In the same way, the coaches knew they could talk to the captains about keeping their fingers on the pulse of the team. When you’re in the unfortunate situation of needing to discipline a player for violating a rule, you need to have the captains backing you up to maintain the unity of the team. Sometimes the captains try to keep an eye on a guy if he’s having personal problems or emotional issues. It’s a vital role they play, and I relied on Gary and Peyton for input, even when things were going well and we were rolling. I’d say that I was thinking about giving the team an extra day off, and they’d say, maybe we could just practice without pads.

There’s a different approach you have to take when coaching the pros versus high school or college. First and foremost, you’re coaching twenty-two- and thirty-two-year-old guys. You don’t want them to see you in the narrow role of ultimate authority. You want to be their leader, not their dictator. In the pros, you’re coaching guys with mature thought processes and lots of experience. You’re not instructing them so much as leading them. You have to win their faith in you and in your system.

If the captains are on board, the rest of the team will come around. The captains are bound to be closer to them in a player-to-player relationship. Gary’s influence was yet another way he was so valuable to the Colts’ success: he helped me get my point across through reinforcement at the peer level. He would show the others that by working hard, doing the basics the right way all the time, this is how we do it in Indy. I know these things sound clichéd from a coach, but when they’re communicated by a player, that’s how teams win.

Gary was instrumental in pulling our defense together. Frankly, we were just as worried in games when Gary wasn’t playing as when Peyton wasn’t out there. His absence might not have been as noticeable as Peyton’s because he didn’t handle the ball, but he was just as important to the defense and to the team.

Fans only get to see the players for three hours on Sunday. I was privileged to get a fuller view of number fifty-eight. I was able to see him interact with teammates all week in practice. I was fortunate to know what he was doing in the community. I was lucky to see the many sides of Gary Brackett that so few fans got to know. That broader perspective made things much richer for me. In fact, the only thing I miss about coaching is seeing guys grow from twenty-two-year-old free agents to thirty-year-old captains. That’s what transforms the coach-player relationship in the pros, and that’s also what made our teams in Indy so unique and, I believe, so successful.

Gary was exemplary in many ways, on and off the field. I remember when we played Kansas City on Halloween in 2004. We had had a very good year in 2003, but we lost to the Patriots in the championship game. But having made it that far reinforced the belief that we were a great team, if we performed up to our potential, and many people picked us to go all the way the next year.

Well, we lost that game to KC despite scoring 35 points. We knew we had a very good defense even if it didn’t show that night. Some players were expecting the coaches to be upset, but to their surprise, we didn’t yell. In the locker room when it was over, I told them that we simply needed to play up to our ability and we’d be fine. I remember Gary coming to me afterward and saying, “That’s exactly what we needed to hear, Coach.” It was important to know that Gary and I were on same page. It was also important to have him later say, “I have confidence in these guys. We’ll get it done.”

Another unforgettable play by Gary came again in a game we lost. We were playing the Steelers in the 2006 divisional championship. They jumped out to an early lead, but we were fighting back. Late in the fourth quarter, Pittsburgh had stopped us, got the ball back, and they were close to the goal line. It was an almost impossible situation, with everyone on their team just trying to protect the ball and run out the clock. Gary hit Jerome Bettis head-on and caused a fumble, which we should have run back all the way to win that game. It was so poignant, as Gary essentially willed himself to do whatever it took to win, watching as he led the charge that came so close to winning that game.

Nonetheless, I believe that what I will remember most about Gary Brackett is when we met in my office and he told me, “I need to give my brother a bone marrow transplant.” That’s when I found out the whole story of his family. Gary made clear to me during our conversation that he could handle all that trauma and that it wasn’t going to negatively affect his performance on the field.

Everyone in the Colts’ organization was hoping and praying that everything would turn out all right. Gary was committed to overcoming every obstacle that stood in his way. He knew he had to do this because he was a match, and it was the right thing to do for his family, but he was just as concerned about the team and the effect this might have on them. He told me, “Don’t worry about me, Coach. I’ll do what I have to do to be ready.” Through it all, he was still concerned about his teammates. That’s what makes a captain. That’s what makes a leader.

Taking care of your family and community is very important to me, and I’m just as proud of those things as I am about what our team accomplished. Establishing priorities about what’s truly most important for young men was explained to me first when I was a rookie with the Steelers. Art Rooney, the owner of the team, would sit down with the new players every year and tell them, “You’re going to have a lot of fun playing professional football. But don’t ever forget that you’re also representing this city and this team. You have to understand your status and don’t take it for granted.” I tried to pass that approach along to all the teams I coached.

It’s great to be a Colt, I tell the team. It’s a great lifestyle. Don’t forget, though, your responsibility off the field as well. Playing well, playing to win on Sunday is important. But there’s also the rest of the week when you are a citizen, part of this community.

That’s what it’s all about—encouraging young people and spending time at high schools, teaching kids about the value of education and helping them deal with their problems. Gary, because of his experiences, has developed an amazing compassion that makes him special. When he shares his story, he knows to talk not only about the wins, but also about the losses.

You have to remind yourself that the pros are just young men, with the emphasis on young. There will be, on occasion, tragedies that arise with their parents—they are of that age. But to lose both parents and a brother in such a short time, like Gary did, you have to wonder if someone can persevere through all that. You can’t downplay ability, because it’s not all intangibles and emotion, and this is a very tough, very physical game; so the player’s mind has to be just as strong as his body. Gary’s experiences of fighting for a place on the team, at every level, and then fighting through seasons when the team was not winning, those experiences tempered him. Those ordeals helped make him strong enough to face the bigger crises in his personal life.

When you suffer those moments that emotionally take the air out of you, if and how you come back determines how you will fare in life. It’s how you come back from the losses of life, not losses of games, that defines you as a team and as person. The Colts suffered many devastating losses off the field, starting in ’03 with Gary’s family, my son in ’05, and Reggie Wayne’s brother in ’06. These events are not something you prepare for as a coach as you’re trying to get your team ready to play on Sunday. Through it all, our team would always come together, drawing closer, getting stronger through this support.

Because of Gary’s family experience, his role as captain became even more crucial during those times. To be Gary’s age and understand that leading a team with perseverance is more gratifying than any game-wining play is simply incredible. But that’s who Gary is—a very brave, tough, thoughtful, and caring man who’s destined for even greater things in life.