Читать книгу Akhmed and the Atomic Matzo Balls - Gary Buslik - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThree

HENRI CHARBONNAY, COMMERCE MINISTER OF HAITI, thrust his kisser at his island’s western shoreline three thousand feet below the Cessna and, as if he had never experienced glass before, whacked his face and made his nose bleed.

“You quite all right, there, Mr. Minister?” shouted Alex Gleason, chapter head of the British West Indies Benevolence Club, over the propeller roar. Gleason was convinced that the commerce minister was a cretin and probably a danger to others as well as himself.

“Byen, byen,” the minister, bleeding into an airsickness bag, assured him.

Gleason had let the imbecile talk him into taking the plane to view the country’s catastrophic erosion. As if Gleason’s file folder crammed with UN environmental reports, Red Cross disaster records, UNESCO health, nutritional, and mortality crisis bulletins, and U.S. Geodetic satellite photos—which even more dramatically showed the vast delta of Haitian topsoil dissolving into the leeward sea—were somehow not enough to convince the Benevolences to name Haiti its donee of the year. Gleason strongly suspected that the commerce minister was so bored out of his skull—Haiti having had no real commerce for the last, oh, two hundred years—that almost any diversion, including breaking his nose, was more appealing than sitting in his office swatting flies. Besides, Charbonnay, like his ministerial colleagues, knew graft opportunity when he smelled it—said sense of smell being as highly developed in Haitian olfactory membranes as hearing is to Haitian tympanic bones when voodoo drums thump over hill and dale—and, in order to make damn well sure that Henri Charbonnay and only Henri Charbonnay would be the legitimate beneficiary of any illegitimate remittances, he wished to impress on Gleason his power and importance by pretending that this was his personal airplane at his ministerial beck and call, a charade that would have been hilarious if it hadn’t been so pathetic, because evidently Henri thought you could smash your face against an airplane window and people with money to hand out would not think of you as an incompetent moron.

“I’ve seen quite enough,” Gleason shouted over the din of the engine, which had been sputtering anyhow, so it was probably a good idea to get back to terra firma. “No sense dying before the check clears.”

“Quite so, quite so,” the minister agreed, grinning complicitly. He tapped the pilot on the shoulder, lifted his right headphone, and yelled, “Desann!”

An hour later, in the foothills overlooking Port-au-Prince and the sea, the minister and Gleason sat at a white wicker table on Charbonnay’s fretworked veranda, sipping rum punches and munching conch fritters. Unfurled between them, a satellite map of Hispaniola’s western sea shockingly confirmed the massive, Rasputin-beardlike estuary of topsoil runoff the men had observed from the plane.

The minister’s yard was lush with flowering shrubs, a bougainvillea-woven picket fence, yellow-hibiscus hedges, stands of flaming poinsettia, lavender plumbago, and trumpeting morning glories. Iridescent hummingbirds zipped between clusters of oleander and lantana, yellow bananaquits and red-winged bullfinches flitted from railing to sugar bowl, and a nimbus of bees hovered over a koi-speckled lily pond.

“Look here,” scolded the BWI Benevolence head, “after our frightful experience with your previous great-hope-of-the-common-man president, why the devil shouldn’t we be reluctant? We sent all those fat pink pigs to replace your scrawny black ones to start a pork colony for starving people, and when I came back a year later to see how it’s doing, what do you think I saw on the president’s bloody front lawn?”

“All your bloody pink pigs,” confirmed the commerce minister, jutting his lower lip. “The man was a miscreant. A damned thief.”

“Like the bloody rest of you.”

“True, but look how arrogant he was about it. No humility, that one. When we ran him out, do you think he was even good enough to leave the pigs for our next president? They say his girlfriend accidentally left the gate open, but my own theory is that the spiteful cur deliberately released them into the hills! If he couldn’t have them, no one could!”

“A man of the people,” Gleason snorted.

“Still—decorum, you know.”

“Decorum, my foot. I suppose—” But Gleason stopped talking when the servant girl glided out with another plate of fritters.

“ Pa gen pwoblèm,” the minister assured him, patting the girl’s rump, which pleasantly bulged in pinkish-beige stretch pants. “Cléo has no ears for politics.” He winked at Gleason. “Only a tail for her employer.” He turned again to the young woman. “ Wi, cheri?”

“Only legs for my purse,” she replied.

The minister laughed and spanked her bottom. “Later, you naughty girl,” he called as she slipped back into the house. “For the time being, more drink!”

The sun bumped the crown of a distant hill, spilling shadows across the sprawling city, draining its color. A fretwork outline stretched onto Gleason’s map. He set his drink on the border between Haiti and the D.R. “Look here, Henri, this erosion business has to stop. It’s going to kill you all. There, now my conscience is clear.”

The minister shrugged. “These are a very ignorant people. Perhaps it would be nature’s way of—what’s the expression?—thinning the herd?”

“I don’t doubt you’re right, but in the meantime we can’t very well send you another fifty thousand saplings, only to have the peasants keep cutting them down and burning them for fuel. Good heavens, man, can’t someone teach them the concept of foregoing immediate gratification for longer-term good? It’s not bloody brain surgery.”

The minister pouted. “They care more for having babies and eating.”

“It’s not like the first batch came without training. We bloody well explained it takes ten years to reforest. That’s not so long in the scheme of things.”

“The ungrateful wretches claim it’s a lifetime when you’re starving.”

Gleason tapped the photograph. “Look at this mess. There’s barely an inch of topsoil left on this whole side of the island. You can’t keep cutting down trees and expect to keep your blasted dirt, man. One more hurricane like Oscar, and what’s left of your agriculture will be completely done for. Then all the Benevolence trees in the world won’t save your damn black hides.”

“But I can promise you—”

Gleason gazed around the minister’s lush garden. No shortage of topsoil here. “Promise me?!”

Ignoring the insult, Charbonnay, sipping his punch, went on: “The problem was in giving them trees directly, you see.” He gazed at a deforested range of southern hills, where barren streaks of gray runoff made it look like God had wiped his shoes.

“How the devil are we supposed to save your damned ecosystem if we don’t plant trees?”

“What I mean is,” Henri said, slurping, “you should give the trees to the government, and we will sell them the trees.”

“Sell them?! Good grief.”

“You don’t understand the Haitian peasant brain, my good friend. If they purchase a sapling, even for a lowly centime, they will never cut it down until it stops growing. Every year they will come out and stare at their investment and measure how much it has grown from one month to the next. Only when the ‘interest’ stops compounding will they cut it down for fuel or to sell for furniture.”

Gleason crunched an ice cube. “You know, Henri, your wormy mind might have crawled into the truth.”

The minister raised his tumbler. “Mèsi, my friend. To our mutual health.”

“But how can we be sure the farmers will want to buy the trees—even on credit?” Gleason asked.

“Wanting has nothing to do with it,” Henri snorted. “We will merely pass a new law. How many would you like them to buy? Five, ten each?”

Gleason raised his glass. “Your lack of conscience is an inspiration.”

“Thank you once again. But it’s for their own good, dear friend. You see how avaricious they are, without any appreciation for your kindness. They are like infants. We have a responsibility to teach them the value of money, do we not? Teach them that money doesn’t grow on trees.” He coughed with laughter at his own pun, and the hack knotted into a gasping choke. He motioned for Gleason to slap him on his back.

But something strange had caught Gleason’s eye, and he was no longer paying attention to the commerce minister. A denuded oval, perhaps a half-mile wide, scabbed a southern mountainside. This patch of eroded earth was different from the surrounding washed-out land, a more ghostly gray, mounded like a grave. If the mountainside resembled a dying man’s waxy pate, this was a basal-cell carcinoma, a ceraceous mole, a malignant hatchery feasting on its victim’s scalp, gathering strength to metastasize.

Gleason stared at the spot with a terrible premonition. Clouds congealed on the mountain’s brow. A premature chill rose zombie-like from the veranda floorboards. He shivered, and his ice cubes crackled. When the city fell completely into shadow, and distant voodoo drums began their twilight rumblings, the chapter head of the BWI Benevolence Club snapped out of his waking nightmare to glance over at his host, face down on the table, passed out from his pun-guffawing lack of oxygen. Gleason bolted up, frightened. “Cléo!” he yelled into the house. “Come help! Help!”

“I feel like such a failure,” Diane told Les, as she swirled an asparagus spear around a dollop of Hollandaise sauce. A week after she had dropped the bomb on him in his office and his catatonic meltdown, they sat in a cozy booth at Chez le Pitre just west of Chicago’s Gold Coast, Les apparently recovered.

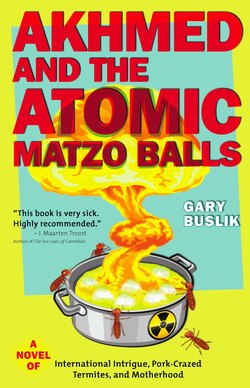

“We wanted to change the world, remember?” she went on. “We were going to, too.” She self-consciously paused, wondering if it was ungrammatical to juxtapose two homophones. But since Les didn’t cast a disapproving look, she assumed that, its awkward (and ill-conceived, to be sure) construction aside, it was probably kosher. “You did your part,” she went on, “ridding literature of all those oppressive European males—Shakespeare and Hemingway and Dickens—but me, what have I done? Matzo balls, that’s what.”

“Matzo balls?” he asked, nibbling his Moët (true champagne, having been produced in France, not that ersatz California excretion, and also containing a French tréma diacritical accent mark over the e).

“I’ve become my mother, plain and simple. No, I mean it. It’s not funny. Remember how I used to mock her? How she would call me to make sure I had enough clean underwear and Tide, how she’d send me all those chocolate coins for Passover? The time she sent that two-pound block of halvah that I didn’t pick up from the post office for a few months, so that by the time I did, it was an ant farm?”

Diane wouldn’t mention how comforting the tiny, industrious pets had been after Les had stopped calling. “It was a good joke at her expense…and now I’m sure my daughter is laughing at me. It’s true, I call her every night for no rational reason. ‘Hello. Fine. Goodbye.’ I’m even starting to talk Yiddish to her. ‘Nu? Vus machst du? Zay gezunt.’ Once a month I send her a jar of matzo ball soup. Can you believe it? Me, bell-bottomed, love-beaded, toe-ringed, hippie-Diane, sweating over a stove, boiling matzo balls?”

“It’s not morphing into your matronly progenitor that’s bothering you,” he offered. “It’s having become”—he crinkled his nose—“middle class.”

She sighed. “What happened, Les? I was going to join the Peace Corps, feed the hungry, build houses in Africa. Instead, I’m rolling matzo meal.”

“But you produced a female progeny.That’s something. The world needs more women. If only women ran the world. Progressive-thinking women,” he hastened to add, “not Margaret Thatchers or, heaven knows, Michele Bachmanns. Again, I use the word heaven in its secular sense.”

“I was sure she would grow up to be everything I wasn’t. Until… this.”

“One door se ferme and another s’ouvrit,” Les assured her.

“Isn’t that just like you.”

“When you told me, I admit the first thing I thought of was my relationship with Chancellor Beebe—how my career was going to be completely deconstructed. Don’t get me wrong. I’d like to be dean. I certainly deserve to be, and, for all its faults, DePewe deserves to have me. Liberal Arts and Sciences could definitely use my superior intelligence and administrative hyper-competence. But it got me cogitating. I’ve been kissing Leona’s posterior for almost three years now, and regardez-moi—I’m still only head of the English Department. After seeing you, I faced the inescapable realization that she’s never going to give up that power over me. Power never gives itself up voluntarily, does it?” he sneered. “There’s your so-called democracy for you. It’s enough to make you want to join forces with—”

He stopped. He pierced her a look. Had he said too much? But no, her eyes were still focused on some faraway galaxy, where couples were always in love.

He cleared his throat. “So,” he said, steering himself back on message, “my realization turned out to be positively epiphanous. It got me to thinking even more globally—figuratively globally, that is. I actually have a daughter now, an heir, a child who wants me in her life, in addition to which I have a former girlfriend who doesn’t despise me—”

“Despise you? Oh, Les, you couldn’t be more—”

“No, please, let me get it off my chest. It’s been swirling around my région d’intérieur for too long. All right, I ratiocinated, so what if I never become dean? So what if I never see Leona socially again? So what if I’m reduced to persona non grata, career-wise—if I’m professionally nihilized? The important thing is, now I have you and Karma and…”

“Angus.”

He studied her again for any sign that she wasn’t buying this. But she just continued to gaze fatuously at her distant galaxy.

“I’ve been given a second chance, Diane, if you’ll pardon the passive construction. How many people can say that? I mean the second-chance part, not the passive-construction part. In any event, you can’t imagine”—he secretly winced—“how much I’m looking forward to meeting her and, um…”

“Angus.”

“The Four Seasons restaurant, you say?”

“Thursday night.”

“I’m fervently anticipatory.”

She smiled at him over entwined fingers. “You’re a mensch, Leslie Fenwich.”

“Who knows, maybe menschdom’s been in here the whole time, subcutaneously. But now, thanks to you, it’s risen to the dermis.”

“And you know what? I still adore your dermis.” She glanced around at the other patrons and felt herself blush. “Maybe that’s the champagne talking.”

He reached over and took her hand. “Truth is nectar of the soul.”

“Who said that? Shakespeare? I mean, Shakesqueer?”

He shook his head. “Fenwich.” He wrist-flicked the sommelier. “I don’t mean immortal soul, of course,” he hastened to add. Thumb in bottle punt, the wine waiter topped off their bubbly. Les tongued the liquid. “So, tell me a little about our future son-in-law.”

“Angus Culvertdale, heir to Global Boffo.”

“A Republican.”

She made a face as if snapping into a jalapeño.

“No social conscience at all?”

“That’s the heck of it, Les. He’s got a heart of gold. He set up his own charitable trust—”

“Tax dodge.”

“—that gives gobs of money to causes we could only dream about. Plus, he treats Karma like a queen—”

“Cunning!”

“Takes her on trips around the world, introduces her to celebrities, buys her expensive jewelry. He bought her a new Mercedes SUV, and they’re not even married yet. A gas-guzzler. Twelve miles to the gallon.”

“Capitalist skullduggery.You won’t fall for it, of course.”

“That’s the worst part of it. I like him. I mean, really like him. He’s sweet and thoughtful and never says a harsh word about anyone. He’s offered to take me to Switzerland with them in November, and I’m embarrassed to say I’m considering it. He’s funny and optimistic and cheerful and completely supportive of everything Karma wants to do, and I just want to squeeze his cheeks to death. I’m so confused.”

“It so happens, I do have one of my brilliant suggestions. It wouldn’t be an entire solution to the problem—more a palliative than a cure—but it would be a start.” He swished bubbly around his molars and swallowed contemplatively. “You know the state is insolvent, and, naturally, this being such a brutally plutocratic country, the universities are always the first to suffer. If the governor would raise income taxes again, fine, but the malefactor is more concerned about not offending wealthy landowners than nurturing our wombs of intellectualism.”

She clung to his every word, trying desperately to hold on, as he dragged her around by his linguistic ankle.

“The department hasn’t hired anyone in five years, and the faculty haven’t gotten a raise in three. It’s abominable, unconscionable, and disgraceful. How do they expect us to attract superior theorists? The best we’d ever be able to snare are literature people. Now, if your…our future son-in-law…”

“Angus.”

“…could be persuaded to include the English Department on his list of foundation recipients? Oh, I know it’s ill-gotten money—no doubt profiting off the poor—but if you, let’s say, could persuade him to add the department to his charitable trust, or however those things work, to the tune of, oh, as much as humanly possible, I believe he could depend on his future father-in-law’s blessing, in terms of walking down the aisle?”

She frowned. “Does it mean that if he won’t—”

He squeezed her hand. “You know me better than that. Of course I will. It’s within the framework of my moral cadre”—he pronounced it cahd-ray. “I’ll walk my daughter down the aisle irregardless—or regardless, if you believe irregardless is a tautology, which I don’t happen to—pardon ending my clause with a preposition. I hope to meet her beforehand too.”

She smiled again.

“That’ll be our little secret for now—leverage, you know? If you make the presentation the correct way—you know, don’t actually conjoin the ideas formally, no ultimatums per se, he’ll undoubtedly seize the opportunity to display his so-called generosity to his prospective in-laws—assuming he’s as self-centeredly charitable as you portray.”

“Brilliant!”

“Précisément. I do feel we have to give him some guidance, in terms of amount? He surely has no idea what dire straits DePewe State is in. Probably never bothered himself with the exigencies of higher callings. I haven’t the faintest idea how much he’d be inclined to contribute. A chair is only a million dollars. Quite spectacular recognition, though. Probably name the cafeteria meatloaf after him. Unless he’s a vegetarian, and then he’ll get the cauliflower.”

“A million dollars?!”

“They arrange payment plans, I’m told.”

“A million dollars,” she murmured, deflatedly.

“Or for the less committed, a hundred thousand could secure an endowment. A family endowment, for that matter. Maybe he’d get the mashed potatoes.”

“A family endowment! Far out!”

“Something the grandchildren would be proud of.”

“Grandchildren! Oy!”

“Then you’d…we would certainly never have to worry about them getting into DePewe. I mean, in the unlikely event their high school grades aren’t stellar.”

“Oh, I’m sure they’ll be brilliant grandchildren.”

“Consider it a safety net, then.” He raised his flute. “To Angus.”

“To Angus.”

“To…”

“Karma.”

“To Karma. And to genius grandchildren.”

She pressed her hands to her cheeks. “Kinders! From your mouth to God’s ears!”

They clinked glasses. Sipping, he muttered, “Whatever.”

The captain of Elysium Cruise Line’s newest and grandest ship, Countess of the Sea, currently docked at the Port of Miami, received an e-mail from his marketing director and sent this reply:

Dear Miss Bjornson:

Let me see if I understand you correctly. A certain apparently very wealthy young woman…the future Mrs. Culvertdale, you say?…has chosen to charter, for her and her bridegroom’s exclusive use, our magnificent new ship, in order to grace us with her wedding ceremony and subsequent honeymoon, during which bride and groom will ply the Eastern Caribbean with a complement of two hundred crew—all because she believes Countess of the Sea resembles a giant wedding cake? Do I have, then, a full understanding of the situation?

To which the marketing director replied:

Dear Captain Pfeffing: This is an outstanding opportunity for us, it being off-season.

To which the captain responded:

Dear Miss Bjornson:

I understood the line to be doing well. The bonuses were certainly generous—which, needless to say, we appreciate.

The marketing director wrote:

Dear Captain Pfeffing: Times aren’t always so wonderful.The industry is just now recovering from the recession, barely, and another economic slowdown seems always around the corner. The business cycle, you know. It’s simply prudent to bury your nuts for the winter.

The captain wrote back:

Dear Miss Bjornson:

Bury my nuts?

The marketing director clarified:

Dear Captain Pfeffing: Not your nuts. Not anyone’s nuts per se. Not any man’s nuts, certainly. We simply see this as an unexpected profit source—a windfall, if you will.

The captain explained:

Dear Miss Bjornson:

The staff works hard all season. Most work twelve, fourteen-hour shifts—very little sleep from December through May. They look forward to relaxing in between. It’s vital to restoring body and soul. I believe I speak for the crew in saying there are more important things than unexpected profit sources. Of course, it’s your prerogative to poll them yourself. Do your own market study, as it were.

The marketing director explained in return:

Dear Captain Pfeffing: Sorry to say, we can’t pick and choose our opportunities. We simply seize them or not, and I dare say, the cruise-line boneyard is littered with skeletons not designed to flex.

The captain replied:

Dear Miss Bjornson:

You’re lecturing me on ship design?

The marketing director replied in return:

Captain: Don’t you think you’re putting the worst possible spin on this? Of course I’m not lecturing you on ship design. Surely you know I didn’t mean that literally.What do I know about ship design? They float, that’s good enough for me. I haven’t the faintest idea how they float, and, frankly, I don’t care. As long as our passengers don’t drown, so we have a chance to sell them cruises in the future, that’s all I’m concerned with. The rest isn’t my business. I don’t even like water, to be honest. And I’m not that crazy about fresh air and sunshine. I’ve grown accustomed to doing without either. But this I do know: we, both you and I, have an obligation not only to ourselves and our staff but to our investors, who pay our salaries whether we like it or not.

I really think you’re letting your pride get in the way.

The captain summed up:

Marketing Director:

Now at last I do understand. Pride ought have nothing to do with it. I’ll be sure to pass that along to my crew.

The marketing director bristled:

Capt.: You know that’s not how I meant it. Threats aren’t productive. Technically it’s not your crew, you know? You don’t sign their paychecks.

The captain bristled back:

Mkt. Dir.:

I’ll pass that along as well.

The marketing director shot:

I was hoping this might go more rationally.

To which there came no reply.

To which the marketing director suggested:

Dear Captain Pfeffing: Perhaps a short phone call might clear up this little misunderstanding.

To which there still came no reply.

To which the marketing director slammed her fist on her keyboard, demolishing the numeric keys. Oh, how she despised that haughty Karma Weinberg. How she wished “the imminent Mrs.Angus Culvertdale” would be tanning herself on the ship’s deck when a giant intergalactic-alien-squid tentacle would pull her into the Bermuda Triangle and force her to breed to freshen its gene pool.

Just not before her honeymoon-cruise check cleared the bank.