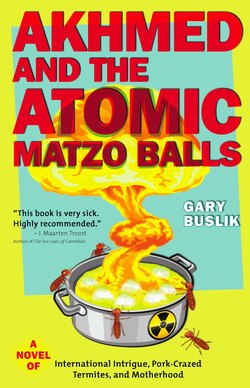

Читать книгу Akhmed and the Atomic Matzo Balls - Gary Buslik - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFour

IN THE RESTAURANT LOBBY OF THE CHICAGO FOUR SEASONS Hotel, Diane nudged Les (and herself) toward their daughter. “Les, meet Karma.” Diane shifted her weight, wiped her palms on her dress, and cleared her throat. “Karma, allow me to introduce you to your, um, well, uh…”

“Father,” Karma said, completing Diane’s sentence with a baleful glance. She turned to Professor Fenwich and offered her hand. “Glad to finally meet you, Popsie.”

Les detected something vaguely sarcastic there. Nevertheless, girding himself, he opened his arms in a well-rehearsed, completely insincere gesture of paternal affability. “Please, call me Les.”

Karma, refusing to step into his embrace, withdrew her hand. “I’ll stick with Popsie.”

He looked her over in the dimness of the elegant eatery, this Gold Coast gastronomical temple to nouveau riche epicurean gluttony (as if you could tell the difference when it came out the other end). Sure enough, even in the impuissant light, he could (unfortunately) see Karma’s resemblance to her picture in Diane’s purse and, necessarily by extension, to himself. Popsie and daughter, mother and future son-in-law—one big happy family.

After shaking his future father-in-law’s hand on behalf of himself and his betrothed, Angus whispered something to the maître d’ and, (despite the languorous lighting) visibly enough for all to see, slipped him a folded hundred-dollar bill, whereupon Karma snapped her fingers for her little tribe to follow him to their window table.

Snapped her fingers.

So right off the bat Little Lord Fauntleroy Culvertdale and his future femme confirmed the impression they had precursorily made on Popsie (being Republicans was abominable enough, but chartering a giant cruise ship for their exclusive use as a bridal suite was beyond the solar system in over-consumptive insufferability).

Nevertheless, Leslie Fenwich, Ph.D.—Professor Leslie Fenwich—had always wondered what it would be like to have dinner at a decadent bourgeois trough like Seasons, overlooking this boulevardian emblem of conspicuous self-indulgence (until now he had dared not try the experiment; aside from the cost, there was always the risk that someone from the university, perhaps sightseeing on Michigan Avenue after having had a properly proletarian Gino’s pizza, would connoiter him leaving said decadent bourgeois trough, imperiling his reputation as a committed proponent of wealth redistribution and dashing his pedagogical ambitions), so Angus’s invitation had held a certain fascination. If anyone from the English Department did happen to spot him, he had only to tell the truth—that he was enduring the unendurable as a sacrifice to the welfare of the university; that to attract big money, you sometimes had to jump into slop with swine. It was disgusting, and average college administrators wouldn’t do it, but, of course, Leslie Fenwich wasn’t average. Whatever he did, he did to perfection—with, as he would sniff to chancellor Beebe, while scrubbing her back in the shower, “full devotion to the cause.”

In preparation for this dinner, he’d had his blazer cleaned and pressed—menial work that marginalized and degraded Third World subalterns, who had immigrated to America hoping to find freedom, only to be forced into a life of unfulfilling labor and subservience to middle-class, white-customer oppressors, forced to adhere to historically Eurocentric, repressive standards of commerce, such as competitive pricing, guarantee of quality, an unblocked fire exit, and rat-free premises; not only did they have to touch their so-called superiors’ personal garments (sometimes of a most metonymically demeaning nature—e.g., pantyhose), they were forced to call them “Mr.” and “Mrs.” (in Les’s case, “Dr.”) and actually thank them for their business, as if they were serfs thanking their feudal lords for not pillorying them in the public square or strapping them to a tree to be eaten alive by hounds. What’s more, also in preparation for this meet-up, having discovered that he had no shirts without secretion stains in the nipple areas, Les had rushed out to Marshall Field’s to buy a new button-down-collar long-sleeve, only to discover that the beloved emporium was no longer Field’s but—get this—Macy’s, the flagship brand of the national corporate behemoth, Federated Department Stores, which unsentimentally devoured venerable regional treasures the way barracuda devour shrimp.

Which was precisely the menu item—shrimp, not barracuda—the Professor now screwed his eyes into on the Season’s appetizer list. North Atlantic jumbo shrimp, detailed and shucked, served on shaved ice with Thousand Island-cilantro dressing and wedge of lemon. Yum. His glance minueting to the right side of the menu, he began to salivate at the description of the various steak dishes. At first he thought he might select the Delmonico New York sirloin au poivre with cognac sauce, but that city reminded him of Macy’s, which was not only the standard bearer of the aforesaid Federated corporate monster but which sponsored the Fifth Avenue Christmas Day parade. Sponsoring anything remotely to do with religion he found so repulsive that his salivary glands immediately shut down, his throat closed up, and he had to quell his gag reflex. What’s more, he recalled his recent shirt-buying excursion, in which, instead of nostalgically finding the cozy and comforting—despite its annual Christmas tree—Marshall Field’s, he had come face to face with the conglomerate-spawned Macy’s, and further in which, being thus forced to suffer the grim truth that nothing was more sacred in corporate America than the almighty bottom line, he had dejectedly shuffled over to Carson Pirie Scott, where instead of that hometown favorite, he found only a boarded-up former department store, now ententacled in construction scaffolding at the bottom of which a gargantuan sign announced the coming of luxury condominiums, starting at “only” $750,000! Good God, who made that kind of money? Not anyone in the damn English Department.

Which was why, despite its come-hither delineation, he now decided to take a pass on the New York pepper steak and order the house specialty instead. That description was no slouch: “Two-inch thick prime Kobe beef, brushed with a light honey glaze, nestled in caramelized onions and knighted with cross-swords of asparagus.” Who wrote this stuff, anyway? Starving linguistics majors?

Unlike the Delmonico, this Kobe meat sat well with Les’s conscience. Kobe was Japanese beef, from Japanese cows that had been fed only the finest grains, never force-fed, never rushed to market. True, at a gazillion dollars a pound (this he knew from listening to National Public Radio, not from the menu, because, in fact, his had no prices listed, Angus having made self-aggrandizingly sure the waiter knew that he was host), the meat did seem a bit pricey, but didn’t we owe them that? Didn’t we racistly and cruelly intern Japanese-Americans at the start of World War II? Didn’t we murder, maim, and genetically deform thousands of their civilians—the elderly, women, children, handicapped—by dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki—vile, unnecessary, barbarous acts whose only true motive was a show of force that would ensure the supremacy of the American military-industrial complex? Not to mention that sickening newsreel footage of the mushroom cloud rising behind the Enola Gay, shown in every theater in the United States, reducing unspeakable and gratuitous human suffering to petty bourgeois entertainment? See melting flesh, pop a licorice. Not that anyone could ever make up for that savagery or the hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of innocent lives America had destroyed in its wars of military occupation, cultural hegemony, and economic imperialism, but didn’t the collectively and historically culpable have the responsibility to at least try? Wouldn’t ordering Japanese meat be the least Professor Leslie Fenwich could do? Not that Les himself, personally, was guilty, of course. Anyone who knew him would understand that he was thinking synecdochically—which he liked to do.

So he was all set to order the Kobe, his salivary glands once more in full shock and awe, his fingernails scraping the silk-lined menu in happy and (after his department-store running-around, shirt-buying ordeal) ravenous anticipation, his throat again as wide and wet as Tokyo Bay, when Diane furtively leaned over to him and whispered, “Don’t forget, strictly vegetarian.”

A blinding flash of light. Reflexively, he looked up from his menu to the other side of the table, but it was only Angus smiling fatuously at his soon-to-be bride, who was gulping her Dom P. with one hand and pointing at her dinner roll with the other, indicating to soon-to-be Mr. Karma to butter her a morsel.

“What?” Leslie whispered back.

“Don’t order any meat.” Diane nodded at their daughter. “We have to set a good example.”

And so, trembling with Kobe-anticipation-deficiency—a term he immediately coined and about which he might write a scholarly article for Verbatim: The Language Bi-Quarterly , either from his office or, if he failed to finish dinner without murdering all three of these horrible creatures, his prison cell—he wound up ordering the pasta Olivia with broccoli and pigeon peas with a side of potatoes au gratin, holding the cheese because cheese comes from cows, and it’s not enough not to eat the goddamn cows, no ma’am, you also can’t eat their goddamn cheese—like they even care. Like it’s not a tad too late for Democrat Mom to be setting a good example for Republican daughter—the same daughter who currently wouldn’t stop complaining, loudly enough for the entire restaurant to hear, about everything in sight, including but not limited to the awful service, the stink of the waiter, his unpolished fingernails, the anemic shrimp, wilted lettuce, dry tomatoes, tasteless carrots, unabsorbent napkin, cheap perfume of the “low-class bitch” sitting two tables over, inadequate leg room, inane Muzak, clanking dishes, streaked windows, dusty chandelier, tarnished silverware, thin salad dressing, hard rolls, tasteless tie on the “appliance salesman” sitting at the next table, improperly deflected air conditioning, and rancid breath of said daughter’s fiancé.

In the meantime, lovesick, puppy-eyed, obsequious Angus—butter-spreading-for-his-betrothed, humongous-blood-diamond-ring-giving, O’Reilly Factor-watching, Armani-tie-wearing, Polo-argyle-sock-wearing, Bruno-Magli-loafer-tapping, snort-laughing, chewing-with-mouth-open-eating, calling-in-trades-to-his-Hong-Kong-exchange-cell-phoning Angus—ordered a guess what? Correct. Flaccid-cheeked, Alfred E. Newman-eared Angus Culvertdale ordered the son-of-a-bitching Delmonico New York sirloin au poivre in cognac sauce—with a called-in-advance side order of macaroni and fucking cheese.

As Professor Leslie Fenwich—Popsie—sat nibbling his disgusting broccoli and trying to figure out how he might familiacide this threesome, in view of the fact that, even though he was philosophically opposed to capital punishment if for no other reason than that it included the word capital, if he himself had to go to the electric chair, it might be worth it, he watched his biological daughter eat so much of her future groom’s steak au poivre off his plate, mopping it in his cognac sauce (complaining about it the whole time), that Angus himself got very little of it down his own materialistic gullet and so ordered a second, this time Kobe (!) steak for himself and polished off the last of this follow-up cut while Popsie was sucking his final sprig of parsley.

On the outskirts of Havana, Cuba, on the rooftop of an eighteenth-century former mansion, Akhmed, his translator Hazeem, and the leaders of two other countries sat eating a splendid parador lunch of grilled sea bass, creole shrimp, olive oil-braised chicken, honeyed ham, spicy rice and beans, steaming potatoes, and mixed salad with pepper-mayonnaise dressing. The president of Venezuela washed down a mouthful of meat with a sip of Heineken from a straw and belched, accidentally launching a shard of ham onto the Iranian president’s forehead. The Venezuelan apologized to the Iranian’s translator. Interlingual babble was exchanged, Akhmed speaking with his mouth full. He flicked the meat off his face onto the concrete floor, where a scrawny blackbird pounced on it and hobbled away behind a vine-threaded trellis. Hazeem assured the South American leader that no harm had been done, either to feelings or international relations. Akhmed washed down his own mouthful of lunch with a swig of Tab, a supply of which he had brought from Tehran, turned and, again through Hazeem, complimented their host, the president of Cuba, on such a magnificent meal—considering that other products and services in his country were total shit. “Do I use the term correctly?” the Iranian president asked.

When they had first arranged this meeting, they had considered speaking English, which they all managed pretty well, but decided against it on principle. Hazeem used the word wonderful instead of shit.

“Pork makes you stupid,” said Akhmed, with an air of superiority. He plucked his napkin-bib from his shirt, crumpled it into a pile next to his plate, and, turning to the Cuban president, said, “Now, shall we discuss our business, El Maximo?”

But his host pretended not to hear.

“El Maximo?”

“Code names,” the Venezuelan whispered urgently, glancing around, focusing narrow-eyed on the blackbird. “American spies are everywhere.”

“Code names,” Hazeem repeated in Farsi.

Akhmed sighed forbearingly. He turned again to the Cuban president. “Okay. I mean…Lovey.”

El Presidente clapped his hands and giggled with joy.

In addition to having agreed not to speak English, they had also decided to always use their code names. This was the Cuban leader’s idea, as were the names themselves. The Venezuelan went along with it because he so admired his revolutionary mentor, and Akhmed thought it was infantile and moronic but acceded anyway because it seemed a harmless enough way to humor these nitwits. And so the Venezuelan president became “Thurston,” the Cuban leader “Lovey,” and the Iranian “Little Buddy.”The Cuban had written these names on slips of paper, distributed them for memorization, reclaimed the scraps, counted all three to make sure none were missing, basted them with a smidge of sofrito sauce, and then, for obvious reasons, swallowed them.

“Business?” Akhmed reminded them, squeezing his crumpled napkin like a tension ball. “Lovey? Thurston?”

“The Yanquis misuse their pigs,” Lovey declared, swishing Havana Club rum around his cheeks, gargling, and, not sure what to do next, turning to Thurston.

“Swallow,” said the Venezuelan.

The Cuban complied. He wiped a trickle from his beard with the back of his hand. “They feed them massive amounts of grain that could feed the starving children of the world. Look at us: our pigs are thin and hungry—good socialist pigs.”

Thurston belched percussively.

“Our plan?” said Akhmed—Little Buddy—squeezing his napkin harder.

“Fine, thank you,” answered the Cuban.

“The Americans are cruel to their animals,” Thurston pointed out. “They fry their chickens without making them fight and kill each other first.” He raised his finger. “Undignified.”

“Our chickens we choke,” Lovey added proudly.

The waitress came with another tray of food.

Akhmed asked if it was safe to talk with her nearby.

“Cecilia is one of us,” the Cuban president declared. He reached over to pinch her buttock, but she scooted out of range, so he pinched his own buttock instead. “A loyal socialist. Her mother is head of her local CDR, and the parador is fully licensed.Yes so, Cecilia?”

“Yes, Maximum Leader, all paperwork up to date. We accept only Yanqui dollars and give change only in Cuban pesos.”

“You see,” he told his guests, “she is completely trustworthy. Her own grandfather was among the forces defending our nation against the imperialists at the Bay of Pigs, for which I awarded him a…” He searched his memory.

“Medal?” Akhmed suggested.

“No, a goat. That’s it, I awarded him a goat. For a moment I couldn’t recall which farm animals we were working with in those days, until I remembered that we have never given out anything other than goats and chickens, and in those glorious days we actually still had goats, so by deduction, I realized there was a better than fifty-fifty chance we awarded his bravery with a goat. Quite maximum of me, no?”

“A goat is worth far more than a medal,” the Venezuelan president said, picking his teeth with a fingernail. “Only the Americans give useless medals.”

“You can’t eat a medal!” Akhmed agreed.

“More drinks, Cecilia,” Lovey called through the doorway.

“She’s a looker,” said the Venezuelan, sucking his teeth. “I wonder if she screams out manifesto in the throes of passion.”

“I might have been married to her mother,” the Cuban leader replied. “I don’t quite recall, but I’m sure it’s written down somewhere. I’ll ask my brother.”

Growing impatient with the nonsensical ramblings of these Hispanic nincompoops, Akhmed sought once again to get the conversation on track. “So, our plan is almost one hundred percent operational, is it not?” he asked his co-conspirators.

“They have just now poured the foundation,” Lovey answered, nodding over the roof’s railing at a construction site next door. He waved his cigar to the security guard, who was sitting in front of the fresh cement to make sure no children came to deface it with seditious slogans like RESCUE US FROM THIS MARXIST HELL. “The concrete is still wet, if you would like to engrave your initials. Especially you”—he momentarily forgot the Venezuelan’s code name—“since it is your donation with which we are building this magnificent new Museum of the Revolution.”

“I’m not talking about those plans,” Akhmed sniped. “I’m talking about the reason I came. You know…killing the Great Satan, bringing the imperialist dogs to their knees, destroying capitalism and Western-style democracy. Draining that Zionist swamp.”

“Israel must be destroyed,” the South American dictator agreed.

“No, you imbeciles. Not Israel!” Akhmed shouted, stomping his foot. “Miami Beach! Doesn’t anyone listen to me? Is it because I’m short? Good things come in small packages. My own mother told me that before I had her beaten to death! Look at Napoleon! Hitler was no circus giant, I assure you. I know on good authority that he wore lifts in his boots and a contraption in his cap that gave his head an extra couple of inches. What’s wrong with you people? We can’t destroy Israel. We need Israel!” He turned to Thurston with a torching glare. “Who do you think caters our stonings?! It’s Miami we don’t need! Miami Beach! Remember our plan? My plan!”

“Mellow out, my tiny friend,” the Venezuelan suggested.

“I don’t want to mellow out! I want to destroy America! I’m not tiny! In my country, I’m average, maybe even a little taller than average! What do you want from me?! How come you nicknamed me ‘Little Buddy’ unless you think I’m short?”

“Would you rather be ‘Ginger’?” suggested El Max. “That would be all right with me.”

“Me too,” agreed the Venezuelan. “Ginger it is.”

“No!” Akhmed blared. “Not Ginger! What’s wrong with you people?! Do I look even vaguely like Ginger?”

“How about ‘Minnow,’ then?”

Akhmed cut the Cuban a withering stare.

“Minnow would be good,” agreed the Venezuelan.

“Okay, okay, I’ll be Little Buddy.”

“Whichever you prefer.”

“Either or.”

Cecilia brought a fresh round.

“Too much caffeine in his soda, perhaps,” the Cuban suggested to his fellow Latin American tyrant. Not recalling what the ashtray in front of him was for, he extinguished his cigar on his knee, sipped his new rum and, with a sigh, said, “All right, my dear…Little Buddy?…let’s talk about the plan.”

“My plan!”

“All right, your plan.”

“I’m sorry I lost my temper,” Akhmed said. “Look, you’re the one who wants to obliterate those expatriate Cubans before you die.”

“My legacy,” Lovey agreed. “Personally, I have nothing against Jews, though. I like them, if you want to know.”

“Well, I don’t want to know, all right? I want to kill them without adversely affecting our catering needs, and you want to kill Miami Cubans, and Thurston wants to shut down the oil refinery operations off the Florida coast. Win-win-win. Do we have a plan, or don’t we?”

“Eat more beans,” the Cuban president said. “Don’t you like our beans?”

“I like your beans fine! Where are we with our plan?!”

Thurston farted—a long bass note. “You try it,” he told the Iranian leader.

“I don’t want to fart. I want to destroy the Great Satan.”

“Don’t be ashamed,” Lovey said. “It’s a compliment to our beans.”

The Venezuelan president leaned over to his Cuban comrade and, ruffling his own shirt, whispered, “Does this make me look fat?”

Akhmed sighed. “All right, all right. Tell me where we are with our plan, and I promise to fart.”

The Latinos’ glances locked. They weren’t sure they could trust the little cockroach. “You go first,” Thurston said.

Akhmed rolled his eyeballs. “I flew all the way from Tehran to discuss the mission. You think it was a picnic? Iranian Air isn’t exactly Funjet. You can’t even make out what the flight attendants are saying behind those burqas. Did she say ‘your vest is under the seat’ or ‘your testes smell worse than my feet’? ‘Yank the string to inflate’ or ‘spank your wang and gyrate’? It’s maddening. Are you supposed to ask for a pillow or throw her out of the plane? And you try flying on an airline that has beaded curtains for lavatory doors and sand for toilet paper.”

“That’s nothing,” the Venezuelan leader protested with a wave. “Try flying out of San Juan sometime! Screaming Puerto Rican kids running up and down the aisles, squirting you with water pistols. One time we had to make an emergency landing, and they found one of the little brats wedged behind the altimeter.”

“I like to fly,” the Cuban piped. “My feet swell and get stuck in my combat boots, so I have a good excuse for never taking them off. I also go crazy for pedal cabs.When I was in Vietnam, I hired a girl to take me around for days, just so I could stare at her rump.”

“What about Caracas women? They have good rumps.”

“I’m not saying they don’t.”

“Stop!” Akhmed wailed. “Why do you have to always do me one better? Is it because I’m short?”

Their host called to Cecilia, “Get Little Buddy a nice bowl of three-bean soup.”

“I don’t want soup! I want to discuss the mission! I’ve already proven my goodwill. I’ll fart only after we discuss the mission!”

Lovey, puckering, and Thurston, running his tongue around the inside of his lip, passed each other nods. “All right, my friend,” said the Cuban leader. “We’ll discuss the mission first. But at least cross your heart about the fart.”

Akhmed gazed dementedly at his co-tyrants, as if wanting to impale them on his fork. Instead, he sighed, lowered the utensil, and crossed his heart.

“You have to say it,” the Venezuelan insisted.

“Okay! I cross my heart!”

“I’m satisfied.”

“Me too.”

“Then let’s get on with business,” Akhmed barked.

“I like business!” exclaimed Lovey.

“The mission,” Thurston agreed, sucking a garbanzo.

Akhmed’s glance careened from one cohort to the other. “Was that so hard?”

“I guess not,” the Venezuelan admitted.

“The instrument of devastation is almost ready,”Akhmed said. “Any day now. All we are waiting for is your martyr.”

His colleagues fidgeted.

“What?” Akhmed, smelling a rat, demanded.

“There’s a slight glitch in the martyr department,” Thurston explained. “Face it, these people are basically Christians. Sad to say, they’d rather sit around praying to Jesus all day than strap explosives to themselves and blow up civilians. Go figure.”

“It’s not possible.”

“’Fraid so,” added Lovey. “Plus, they like music.”

“Music!”

“We have no churches,” the Cuban clarified. “So they listen to music.”

“How are we supposed to destroy Western civilization if they listen to music?! Martyrs hate music!”

“Look,” the Venezuelan reassured him, “we’re working on it. We’ll figure something out. We’ll contact the Professor in Chicago. He’s a jackass, but at least he’s a Ph.D. jackass.”

“A brilliant jackass,” Lovey said, choking back a laugh.

“I never liked the blundering fool,” Akhmed reminded them. “He’s a buttocks-kissing toady.”

“Precisely. Plus, he was raised in Miami,” Thurston reminded him in return, “so he may know someone of our particular mindset. Which is why Skipper suggested we bring him onboard as a standby. That, and the fact that he despises America as much as we do. If not an actual martyr per se, he may know of at least a reliable…courier, shall we say?”

Akhmed puckered, unconvinced.

“Meanwhile,” Thurston went on, “our engineers are working on the satellite signal transducer. They’re arranging a final experiment as we speak. It should only be a matter of days.”

Akhmed’s eyes narrowed. “Days?”

“Chill out, my man. Cecilia! Bring Little Buddy a dish of ice cream.”

“Ice cream? Well, yes, I do like ice cream. What flavor, may I ask?”

“We have a complete variety,” Cecilia said, without a hint of sarcasm.

“You’re joking?”

“Name a flavor.”

Akhmed rubbed his hands. “Spumoni!”

“Spumoni it is. Also, we’re testing a new flavor of the month—Mango Schmango. Would you like to try some?”

He licked his lips. “Mango Schmango? Sounds intriguing. Yes, yes, I believe I would.”

“By itself or with spumoni?”

“I can have both. Really?”

“Of course.We Cubanos are nothing if not good hosts.”

“I can see that.”

“Besides, you are the president of Iran.”

Akhmed puffed his cheeks. “Then, yes, I believe I will have them both. When in Rome—”

“Spumoni and Mango Schmango, coming up.” She winked furtively at her own president, who swallowed a giggle. “Would you like whipped cream?” she asked the Iranian.

“You’re kidding.”

“How about a nice cherry?”

“I’m not a cherry man, but I do love whipped cream! Whipped is good! And I’m crazy about nuts.”

“And a little hot fudge?” Lovey asked.“Quite the thing.”

“Fudge! Oh, this is wonderful!” Akhmed exclaimed. “I feel completely relaxed now. I’m sorry I got upset before, my good comrades.”

“No problema. Cecilia, bring the man his dessert.”

She glided into the house.

Akhmed smacked his lips. “Hot fudge!”

“Aren’t you forgetting something?” Lovey asked.

“Your promise,” Thurston, blowing bubbles with his straw, reminded him.

“Really, gentlemen—”

“Now, Little Buddy,” the Cuban leader scolded. “I won’t have you going back on your promise. It’s a matter of trust—international goodwill.”

“Well, if you put it like that.” And just as Cecilia stepped back out with a drooping, unadorned, mostly melted glob of vanilla ice cream, Akhmed let out a pipsqueak peep of intestinal gas. Cecilia gazed at Lovey; Lovey gazed at Thurston;Thurston gazed at Cecilia, and they all burst out in a collective, doubled-over, gasping guffaw.

Not Hazeem, though. He knew better.

In truth, Hazeem was uneasy having sat in on the meetings with those three witless troublemakers, bearing witness to the mischief percolating in their ninny brains. He had not asked for this assignment but, as usual, had been conscripted by the head ninny, Akhmed. True, back in Iran and other venues supportive of Akhmed’s various zany schemes and antics, Hazeem had been present during many meetings in which various bizarre and asinine ideas were exchanged to drive Israel into the sea, wipe Christianity off the map of Europe, reestablish the continent to pre-Crusades demography, and other-such lunatic notions.

But while this cabal’s lame-brained scheme, which they had goofily named “Operation Castaways’ Revenge,” was in a class of nuttiness by itself, the truth was, it was tinged with just enough real danger to give Hazeem a vague premonition of disaster. They weren’t in the Middle East anymore—they were in the Western Hemisphere, where even before 9/11 the United States did not put up with anti-American mischief, and post-9/11 had, as the Venezuelan dictator pointed out, spies everywhere.

So, yes, it was easy for Hazeem himself to chuckle at the loony ambitiousness of their plan: how they were going to find some poor sucker to carry Akhmed’s radioactive matzo balls into Miami and detonate them with conventional explosives from afar by radio transmitter, to kill many Jews and former Cubans and wreak havoc on American gasoline prices and create economic chaos and ensure the destruction of imperialist bullies and lay the groundwork for a rise of the oppressed and, not coincidentally, Muslims, and be El Maximo’s parting gift to the nation that had rejected him as a baseball pitcher. Easy for Hazeem to giggle at because he knew the degree to which these three so-called national leaders were such bungling boobs, and that their plan for international upheaval would eventually amount to nothing more destructive than Akhmed’s retarded little fart.

On the other hand, he also knew that America, not appreciating the inevitability of these three stooges running into one another and knocking themselves out cold, would, once it caught wind of Castaways’ Revenge, not find Little Buddy’s, Thurston’s, and Lovey’s bumbling incompetence the least bit funny.

There was something else that disturbed Hazeem, something ominous. When, as Cecilia was clearing off their table, the smirking Venezuelan greaseball, deliberately in plain view of everyone, stuck a five-hundred-peso bill down her bodice, his fingers attempting to massage her breasts (there could not be enough hot water in all of Cuba to wash away his filth), Hazeem for an instant had a dark premonition that perhaps at least one of these seeming nincompoops was not quite as incompetent as he appeared—that there was more cunning, calculating evil here than met the eye. A shiver ran through him. He feared for the innocent parador owner, who had overheard much—perhaps too much—and he feared for other unwitting witnesses and for innocent Americans.

And, yes, he feared for himself.