Читать книгу Butcher - Gary C. King - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

ОглавлениеThe city of Vancouver, British Columbia, with a metropolitan area population of 2,249,725, is the largest metro area in the western part of Canada and the third largest in that country. Located along the coast and sheltered from the Pacific Ocean by Vancouver Island, the major seaport is ethnically diverse, with 43 percent of the area’s residents speaking a first language other than English, and is ranked fourth in population density for a major city on the North American continent, behind only New York City, San Francisco, and Mexico City. Because of its rapid growth, it is expected to take over the number two spot by 2021. Idyllic in appearance because of its surroundings of natural beauty, Vancouver is repeatedly ranked as one of the world’s most livable cities. In Canada it is among the most expensive places in which to live. But Vancouver is a major city, and with that distinction comes the grim reality that, like all major cities, it has a dark side that most tourists rarely get, or even want, to see.

One of Vancouver’s unpleasant sides, an understatement to be sure, is its Downtown Eastside, also known as Low Track, long recognized as the poorest neighborhood in all of Canada. Rife with heroin addicts and prostitutes, Low Track is an area of Vancouver where misery and despair rarely—if ever—subside. The area abounds in grubby tenements, some of which are not fit for human habitation, run-down hotels that can easily be described as flophouses, and many of its back alleys and some of its streets are just plain filthy. Cigarette butts, used hypodermic needles discarded by addicts, and empty liquor and beer bottles are strewn about and broken. Discarded articles of furniture, such as sofas, chairs, and mattresses, which some of the homeless use to sleep on, can be found without having to look very hard. The smell of urine and vomit is often overpowering, and used condoms discarded by hookers or their johns are a frequent sight. The sounds of emergency vehicle sirens are frequent, day and night—the police are either making drug busts or other arrests, or medical teams are rushing to the scene of daily drug overdoses. It is also known as the place where many of the resident prostitutes began disappearing in the late 1970s and continued vanishing past the turn of the century. Few people would dispute that Low Track is aptly named.

A number of theories about what may have happened to the missing women have surfaced over the years and range from opinions that one or more serial killers were at work, such as a copycat of the “Green River Killer,” to hookers who visited the freighters that docked in the city’s harbor, only blocks from Low Track, and were kidnapped. The women were kept as sex slaves, only to be thrown overboard at sea when the sailors were finished with them.

Finding out what happened to the missing women has been especially troubling for the police who, according to Vancouver police constable Anne Drennan, had few leads with which to work because in most cases the police didn’t even know where the women came from. Were some of the women following the prostitution circuit along the West Coast—Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland, Seattle—only to end up in Vancouver? No one knew, and guesses weren’t good enough to move the investigation forward. For a time the freighter theory seemed viable because there were stories being told among the city’s hookers about women visiting a number of the ships and not returning. Even though such leads were followed up, the police could never find the evidence they needed to line up any suspects connected to the freighters. As a result, the disappearances remained a mystery—and the women continued vanishing without a trace.

Sometime on Wednesday, December 27, 1995, twenty-year-old Diana Melnick joined the ranks of many of the other women in the vicinity of the high-vice area of Hastings and Main who tried to earn enough money to maintain her drug addiction, and to pay for food and a place to sleep, by selling her body to men, many of whom she had never seen before. The brown-eyed young woman, with brown hair, stood five feet two inches tall and weighed barely one hundred pounds. She had been arrested four times during the preceding few months by police officers posing as johns, yet she continued returning to the streets. Even though information about her was limited, the police learned enough to know that she had friends, and she was described as a warm, kind person with compassion for others. She had apparently attended a private high school, and had not been fond of wearing the school’s uniform. She liked to talk about boys, and always looked forward to going to school dances. Diana also liked to listen to heavy metal, and had a passion for horses, according to information that would surface years later.

She was also apparently a very trusting young woman, as evidenced by her desperation to make the money she needed for survival, because at some point that day she willingly slid into a vehicle driven by a man old enough to be her father and was never seen or heard from again. Diana was reported missing two days later from “the back-side alley of hell,” which is how a friend would describe Low Track some six years later.

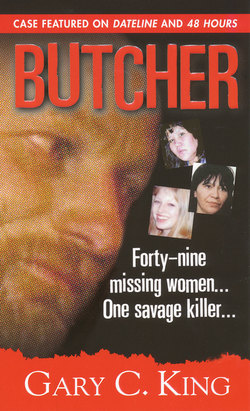

Diana Melnick had been the twenty-fifth woman to be placed on the list that would be compiled by the not-as-yet-formed Joint Missing Women Task Force. She would also be one of the victims that the police would eventually be able to attribute to the serial killer at work here, an unremarkable and otherwise trite forty-seven-year-old pig farmer named Robert William Pickton. Had he not been a violent “backyard butcher,” from appearances alone, he would fit right in as one of the characters on Green Acres or The Beverly Hillbillies. However, because of his violent, predatory ways—along with his hillbilly appearance—he could more easily be compared to one of the murderous characters out of the cult horror film The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. While the first twenty-four missing women would remain among the vanishings that either remained unsolved or were among four out of sixty-nine women that would eventually be located—alive—“Uncle Willie,” as Pickton was also known, was far from finished. In fact, his reign of terror had only just begun.

According to those who knew her, twenty-year-old Tanya Marlo Holyk got along well with most people, and easily fit in when new situations required it. Growing up, long-legged Tanya liked to play basketball, as well as other sports. She also liked to read, and enjoyed doing book reports in school. But influences at home were less than ideal. Her mother, Dixie Purcell, had been a party animal and was known to have brought men, as well as drugs and alcohol, into their home while Tanya was still quite young. Her father had been out of the picture for quite some time, but he was believed to have resided somewhere on Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. A few years before Tanya was born, her mother had given birth to another daughter with another man, but she had given her up for adoption when the girl was only two years old. Dixie had never told either girl that each had a half sister until much later, and the meeting took place at Vancouver International Airport at the same time that Dixie and her first daughter were reunited.

Although her mother claimed to have loved her very much, Tanya spent considerable time living with a cousin in an apartment in downtown Vancouver during her preteen and teenage years. Even though Tanya was three years younger than her cousin, the two got along well together and lived like sisters.

“She taught me lots of things,” Tanya’s cousin said about her. “Some of them good things, some of them not-so-good things. But they all stayed with me.”

At one point Tanya left Vancouver to live with her half sister and her family in the small community of Klemtu, located on Kitasoo Indian Reserve on Swindle Island. As could be expected, Tanya adjusted to the new environment and seemed to enjoy her new life there. She helped out with family chores around the house, and sometimes babysat her half sister’s child. But as she began growing older, Tanya became difficult to handle. Things eventually became so unpleasant that Tanya was sent back to Vancouver.

At one point Tanya became pregnant, and gave birth to a baby boy, the product of a purportedly abusive relationship in which she had gotten hooked on drugs. But Tanya adored her son, opting to leave the relationship and to get clean so that she could properly care for her child. According to her cousin, Tanya moved into an apartment and managed to stay off drugs for approximately two months as she tried to put the pieces of her life back together. Despite her temporary accomplishment her desire for drugs was too much for her to handle.

“She had the access,” her cousin said. “She could get the drugs, she could get the money. She had a friend who would drive her to Vancouver and back. An addiction is an addiction.”

Tanya’s half sister last heard from her when Tanya called her in August 1995 from a detoxification center, at which time she pleaded with her sister to allow her and her young son back into their home. She didn’t want to return to the streets of Vancouver, and although a tentative agreement was made between her and her sister for Tanya and her son to return to her home in Klemtu, the plan fell through. Instead, Tanya went back to the drugs and the streets of Low Track, where, police believe, she met up with Robert Pickton sometime on Tuesday, October 29,1996. Tanya was never seen again and her mother, Dixie, reported her missing on Sunday, November 3, 1996, a little more than a month before her twenty-first birthday.

Her mother said that she continually urged the police to investigate Tanya’s disappearance, but they didn’t take her seriously.

“‘Tanya was just out having fun,’” her mother claimed the police told her. “‘Don’t bother us. Don’t waste our time….’ I just stood there with the phone in my hand for ten minutes, just looking at it.”

She told CNN six years later that the police had chosen to ignore her, but she nonetheless persisted.

Though she knew that it was likely that her daughter had been murdered, probably by Robert Pickton, Dixie Purcell died in January 2006 without ever knowing the final outcome, nor that Tanya would be but one of twenty young women whose deaths might never be served by the scales of justice. In all likelihood, Tanya was butchered by Pickton in the slaughterhouse adjacent to his trailer following an evening of drugs and sex, and her body parts fed to Pickton’s pigs.