Читать книгу Butcher - Gary C. King - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

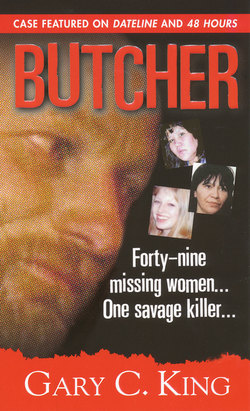

ОглавлениеThe following year, 1997, proved to be a bumper-crop year for Canada’s worst serial killer and the disappearances of Vancouver’s street women. The residents of British Columbia—as well as the police—didn’t have a clue about the bloody carnage that was occurring on a fairly regular basis at the nondescript pig farm in Port Coquitlam, where women were being slaughtered, literally butchered like animals, by a sadistic, maniacal pervert for his own unnatural pleasure. When his lust for pain, terror, and blood—elicited by his actions from his chosen victims—was finally satisfied, the victims were then dismembered, sometimes ground up or sawed into smaller pieces before being fed to his hogs and pigs. These swine would, in turn, and at the proper time, be slaughtered by the same man in the same slaughterhouse where he had butchered many of his human female victims. Then their meat, in the form of pork chops, roasts, loins, and sausages, would be given to unknowing friends and neighbors and sold to the public. Unlike most serial killers, who would dispose of their victims’ bodies in a number of locations or cluster dump them in a single location, often far from the killer’s home, Robert Pickton never even left home to get rid of his victims’ remains. He would pick up his victims who, by the nature of their lifestyles, willingly but unwittingly accompanied him to his pig farm, and most would never leave—until it was time to butcher one of the hogs. Because bodies were not turning up anywhere, the police had little to go on except for a disappearance now and again, and many people merely assumed, including other prostitutes, that Pickton’s victims had simply decided to pack up a small suitcase and move on to another location.

Between January and December 1997, no fewer than fourteen women would turn up missing from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. All fourteen of the disappearances would be attributed to the still-unknown killer’s handiwork, much later, of course, after a thorough investigation. When the police finally agreed that a killer was indeed at work, Robert Pickton would eventually be charged with the murders of six of those women. The list of Vancouver’s missing women was an ever-changing one, with some of the missing taken off the list because they were either found alive or their bodies were found and the cause of death was attributed to something other than the work of the killer. But as names fell off the list, new ones were added to it. By the time the Joint Missing Women Task Force was finally formed, there were still sixty-five names on the list of missing women and one Jane Doe.

The work facing Vancouver’s missing person investigator, Constable Al Howlett, was daunting, to say the least. It seemed like each day he had one or two new files added to the pile already on his desk, and although he and his team remained determined to learn as much as possible about each missing woman, the circumstances of their shady backgrounds made the team’s work all the more difficult.

The neighborhoods where they had to go in search of information didn’t help matters, either. In fact, in the area of Hastings and Main, where a blow job could be bought for ten dollars or a fifteen-minute “suck-and-f***” encounter could be had from any number of working girls for twice that amount, Howlett’s problems were compounded because, particularly in the early days of the disappearances, the working girl’s subculture shied away from talking to the cops about anything at all. At first, with little to build a case upon, Howlett and his team had little choice but to treat the disappearances as unrelated. In truth, it would be another two years before the cops began to put “two and two” together and were able to see that something very horrible was going on here. In the meantime, women continued to disappear on a regular basis.

One of those women was street-tough, twenty-five-year-old Cara Louise Ellis, who often went by the street name of “Nicky Trimble.” When Cara disappeared in January 1997, she was barely three months away from her next birthday. She looked older than her years, and her face clearly showed the ravages of what living on the streets can do to a person. Bisexual and carrying a $500-a-day heroin habit, Cara grew up in Alberta. Cara was diminutive, at four feet eleven inches, and barely weighed ninety pounds. Perhaps it was because of her small stature that she liked to sport a “biker bitch” persona. She also liked tattoos, and had one of a rose on her left shoulder, a heart on her left hand, and a Playboy bunny on her chest. She also had a considerable array of track marks, where she injected her daily doses of heroin that kept her “well”—in other words, from entering withdrawal. She lived in Calgary for a while, where she was raped as a young girl barely into her teens, and where one of her friends, a young hooker, was beaten to death by a trick. It was shortly after those two experiences that Cara, forever a loner, decided to pack up her few belongings and move to Vancouver.

She only met one good friend after reaching Vancouver, and that friendship took a few months to find her, as opposed to her finding it. As it turned out, Cara met another young woman on the streets and the friendship began soon after they moved into a recovery center for women and became roommates. They occasionally worked the streets together, turning tricks to make enough money to keep Cara supplied with heroin and her friend with cocaine. Despite trying to kick their habits in the women’s recovery center, neither had what it took to cast out their demons. The nausea, diarrhea, and severe joint and muscle pain, the effects of withdrawal, always brought Cara back to the heroin. Even a stint at a detoxification facility, Cara lasted only five days before heading back to the streets.

“Unfortunately, she was in a position where the drugs were speaking for her,” said a family member after learning of Cara’s disappearance. “She would basically prostitute herself in order to be able to get the next fix in order to be able to prostitute herself. It was a really vicious cycle.”

Despite her addiction to heroin, Cara’s friend described her as a person who made sure that she could take care of herself. And unlike many of the women in Low Track, Cara kept her clothes as clean as possible and bathed regularly. She also made certain that she had enough heroin on hand for a morning fix, which kept her from getting withdrawal sickness and enabled her to work as a prostitute. For reasons that were never clear, Cara chose to not have any contact with the family she left behind in Alberta, but her relatives never forgot about her.

“She was a great auntie,” said a family member. “She absolutely love(d) my little daughter—she’s not so little anymore. She was a kid at heart when I met her, just a really wonderful girl.”

Although she had confirmed her bisexuality a number of times, Cara told her friend that she wanted a husband and hoped to have children someday. She wanted to be happy, and she wanted to have a better life, said her friend, but she didn’t know how to attain those things. The last time her friend saw her, Cara was in a bad way, sitting in a niche off one of the main streets of Low Track, clutching her drugs in one hand. She smelled bad by then, and she had open sores on her body. She had lost a lot of weight, and her clothes were tattered and dirty. A short time later, on a cold January night, Cara had gotten into a car with an uneducated, but amiable, little man wearing nearly knee-high gum boots who drove her away, taking her from the mean streets of Vancouver—forever.

“Cara vanished,” her friend said. “She just disappeared.”

Over the next few weeks in January 1997, Marie LaLiberte, Stephanie Lane, and Jacqueline Murdock disappeared in a similar manner, although it was never known whether they had gotten into a car with Uncle Willie or not.

Many murders attributed to a serial killer are of the stranger-to-stranger type in which the killer has no known connection to his victims. In the case of Robert Pickton, the police would later learn that he had known or had dealings with at least some of his victims on prior occasions, perhaps engaging in sex with them or merely bringing them to his house trailer to party with him, giving them drugs and money, and then driving them back to Vancouver unharmed. This seemed like a reasonable explanation of why many of his victims felt a strong enough comfort level with him that they did not hesitate to get into his car and drive away with him. This could also, perhaps, help explain why he was able to get away with his cruel and vicious crimes for so long without arousing the curiosity of the community at large or of the police. No one, as will be seen, ever seemed particularly alarmed whenever Uncle Willie showed up in the vicinity of Main and Hastings—at least not at first. Few people saw the evil that lay beneath his skin—until it was too late. Another plausible reason for the lack of concern shown by the police, as well as by the residents of Low Track, at least for a time, when women left with Pickton and did not return, was because their bodies had not turned up anywhere. It seemed entirely possible that Pickton would have been looked at sooner as a suspect if at least some of the bodies of the missing women had been found.

At least one person, however, had seen the evil that lurked inside Robert Pickton. According to a Seattle, Washington, writer, Charles Mudede, and an article of his that appeared in a Seattle weekly called The Stranger, of which Mudede is associate editor, a longshoreman had gone to a Halloween party, perhaps as early as 1996 or 1997, at Pickton’s farm in the 900 block of Dominion Avenue in Port Coquitlam, accompanied by a friend. The party was held inside a building on the farm that Pickton and his brother, Dave, called “Piggy’s Palace.” It was a dark, rainy night when the longshoreman and his friend arrived. The parking area, filled with motorcycles and cars, was muddy. One of the first things the two visitors saw was a large pig being roasted on a spit, and children dressed in Halloween costumes were outside playing in the dark.

“There wasn’t much light,” the longshoreman said. “There were lots of women, who looked like hookers.”

The party, he explained, was outside on the grounds, as well as inside the building and inside a trailer, where they were “doing the wild thing.” People were not only having sex, but they were doing a lot of drugs. He explained that when it came time to eat the pig, he saw Pickton tear it apart with his dirty hands. The sight was sufficient to cause the longshoreman to decide that he wouldn’t be eating anything that evening—at least not while at Pickton’s farm.

He said that at one point he had walked past a shack where a low-wattage light burned dimly above the door, and he could hear machinery running inside. He wasn’t sure what kind of machinery he had heard that night, but it had frightened him terribly.

“Here, I got a death chill,” said the longshoreman. “The hairs raised on the back of my neck and my feet froze to the ground. I didn’t want to be there anymore, so I left and walked home.”

Another party attendee, a woman who said that it had been her first and last time to visit Pickton’s farm, described the partygoers as raunchy, and claimed that a lot of cocaine was being passed around that evening.

“[There were] lots of really, really bad, badass people…. I did not want to be a part of it.”

Piggy’s Palace, however, was more than just a party place, as the cops eventually learned. It was listed in Canadian government records as a nonprofit organization under the name Piggy Palace Good Times Society, and it routinely raised money for any organization that its operators deemed worthy. Piggy’s Palace was located in the 2500 block of Burns Road, adjacent to Pickton’s farm on Dominion Avenue, but several acres away, and was built out of tin—basically it was an elongated tin shed. It was visited not only by many of Port Coquitlam’s average citizens but by the town’s civic leaders, including mayors, members of the city council, businessmen and businesswomen, and so forth. Functions, such as dances and concerts, were held there, the proceeds of which often benefitted local elementary and high schools. At nearly every function roasted pork had been served to the guests, whether they had been civic leaders or badass party animals. Truth is, although one wouldn’t know it by looking at him, Robert Pickton had become a wealthy man, not so much from his commercial pig-farming operation but from the continually increasing value of the land that the pig farm was situated on. By 1996, he no longer needed the money. Although the land had been purchased in 1963 by his father and mother, Leonard and Louise Pickton, for a mere $18,000, it was valued at $7.2 million by 1994. When Leonard and Louise died in the late 1970s, Robert, his brother, Dave, and their sister, Linda, inherited the land. Robert and David remained on the farm, while Linda was sent off to boarding school.

In the autumn of 1994, the Pickton siblings sold off the first significant portion of their land to a holding company for $1.7 million, and town house condominiums promptly went up on the parcel. A short time later, the City of Port Coquitlam purchased another parcel of their land for $1.2 million and installed a park on it. The following year Port Coquitlam’s school district purchased yet another parcel for $2.3 million, and constructed an elementary school on the land. By then, Robert was treating his pig-farming operation more as a hobby than as an income-producing business, and he often merely sold the meat it produced to friends and neighbors, or gave the butchered meat away by holding wild parties. It was also about that time that Pickton’s generosity was becoming known in Low Track—and when people began to notice Vancouver’s women were disappearing.

The one-per-week disappearance average for January slowed to only one in February 1997. Sharon Ward left the Downtown Eastside area sometime that month and never returned. No one has—yet—determined what happened to her.

It wasn’t until March 1997 that another woman’s disappearance would eventually be attributed to Robert Pickton.

Andrea Fay Borhaven, twenty-five, was believed to have disappeared in March 1997, but she was not reported missing, according to the police, until May 18, 1999, for reasons that were not made clear. A wild and tough young woman, she bounced back and forth between her mother and father, as well as between a few other relatives and an occasional stranger, frequently taking advantage of the goodwill shown to her by others. Born in Armstrong, British Columbia, a small town northeast of Port Coquitlam, but still in the southern part of the province, Andrea was often described as a troubled and unhappy little girl who often felt unloved.

She was diagnosed early in her childhood with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and was placed on medication for it at one point. She was smoking marijuana by the time she was thirteen, and was getting into trouble at school. Her mother made her a ward of the court system in an apparent act of desperation to try and get help for her daughter. Andrea was sent to a residential facility for children in another town. After barely two months in the facility, Andrea ran away and stayed with relatives for several months.

Although relatives described Andrea as an intelligent and loving teenager, she seemed to possess little ability to channel her impulses, often harboring feelings that would lead to uncontrollable outbursts, which only added to the growing number of problems she already had. As time went on, her feelings of worthlessness, irrelevance, and despair became worse. Even though she was always welcome to come home, and had the support of her family, she always had difficulty complying with the household’s rules, according to her mother.

“You don’t get into drugs,” her mother would say. “You go back to school or you get a job.”

Her family didn’t know where she was staying much of the time, but she would occasionally show up unannounced with a boyfriend that few mothers and fathers would approve of for their daughter. During such visits she typically asked for money or a temporary place to stay, and family members usually complied. But things often went missing from the homes where she stayed, and family members noticed that Andrea would sell items that they had purchased for her as gifts so that she could obtain money for drugs.

“I asked her on occasion if that’s what she wanted for herself, and she seemed to think that she would never end up there,” addicted and on the streets, that is, said a relative. “But that’s exactly where she ended up.”

Shortly before she disappeared, Andrea’s mother had reason to believe that her daughter wanted to make another attempt at getting clean and off the streets.

“She was coming home,” said her mother. “All her clothes were sent home on the bus. I have all of her clothes. And then I didn’t hear from her.”

Andrea did eventually get off the streets—and into a car that took her on a trip of unimaginable terror and horror—never to return.