Читать книгу John A. Macdonald - Ged Martin - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеOnly Make a Beginning

On July 1, 1867, John A. Macdonald became Canada’s first prime minister. Confederation, as the process was called, split the existing province of Canada, formed in 1841, allowing its two sections, Upper and Lower Canada (Canada West and Canada East), to form the separate units of Ontario and Quebec. They joined New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to become the Dominion of Canada. A talented lawyer, efficient administrator, and prominent figure in Upper Canadian politics, Macdonald had played an important role in creating the new political union.

His family had arrived in Kingston, Ontario, when he was five years old, after the failure of his father’s business in Scotland. They continued to struggle in Canada. At fifteen, he became a clerk in a law office, and worked his way to the top. Years later, a friend confided that he too wanted to become a lawyer, but doubted whether he had the time or resources to study. Macdonald offered sage counsel: “only make a beginning, and you will get through some way or other.” He applied that philosophy to projects such as Confederation and the transcontinental railway, with a combination of determined optimism and practical caution that earned him the grudging nickname “Old Tomorrow.” John A. Macdonald died in office in 1891 after leading the Dominion for nineteen of its first twenty-four years. By then, Canada had expanded to the Pacific and acquired three more provinces (Manitoba, British Columbia, and Prince Edward Island). Newcomers settling the prairies (the future Alberta and Saskatchewan) disrupted traditional lifestyles, and in 1885 some Métis and Native people rose in revolt. It was ironic that Macdonald’s final years were overshadowed by the tragedy of the Riel uprising, since his political philosophy of deal-making compromise had been shaped by the shocking experience of Upper Canada’s 1837 rebellion. Although he rarely spoke of his experience of serving in the government forces in that minor civil war, he learned an enduring lesson about the fragility of Canadian society.

Of course, Canada has changed since Macdonald’s day. The title “Dominion” was no accident: Macdonald intended Ottawa to be the boss, with the provinces as subordinates, not federal partners. The centrepiece of his later years was the Canadian Pacific Railway, completed in 1885 to stiffen the transcontinental nation with a steel spine. Canada’s rail network still handles bulk freight, but trains carry more tourists than travellers. The railway formed part of Macdonald’s National Policy, the 1879 protective tariff that encouraged western Canadians and Maritimers to buy goods mainly manufactured in Ontario and Quebec, a structure finally discarded in the Canada-U.S. Free Trade pact of 1988. John A. Macdonald forged the Conservative Party as a powerful instrument to govern Canada by mobilizing support among both its English- and French-speaking citizens. But, after his time, the party generally failed to win support in French Canada. Political parties evolve new policies as circumstances change: the 1988 continental trade pact was struck by the Conservative government of Brian Mulroney. Macdonald’s Pacific Railway was a partnership between government and a heavily-subsidized private company; Canada’s modern-day Conservative Party champions a free-market economy. John A. Macdonald’s nineteenth-century blueprint cannot function as a straitjacket for twenty-first-century Canada.

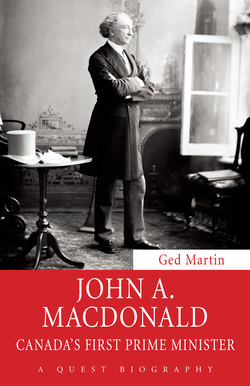

The rising lawyer-politician, John A. Macdonald, about 1856.

Ruling Canada from Ottawa, squabbling with provincial premiers, protecting the country from the Americans — John A. Macdonald can seem a very modern figure. However, social and political values were often different to those of today. Politics was a man’s game. Macdonald was encouraged to enter Parliament by his ambitious mother, Helen (Shaw), but his first wife, Isabella (Clark), who died in 1857, played no part in his campaigns and disliked his involvement. His second wife, Agnes (Bernard), who married him ten years later, was initially snubbed if she dared to offer her opinions. Ultimately, this tough-minded woman became his confidante, but she never made a political speech, nor indeed could she even vote. In 1885, Macdonald considered giving the franchise to women who owned property, but his agenda was conservative, not feminist: women did not vote in any federal election until 1917.

It was an era in which religion formed a public, almost tribal, badge. Until Macdonald solved the issue in 1854, Protestant denominations squabbled over the clergy reserves. A deep schism existed between Protestants and Catholics. Even Macdonald, a generally tolerant person, objected when his own son decided to marry a Catholic. He was first elected, in 1844, as a Protestant politician, backed by a fraternal organization, the Orange Order — fraternal to other Protestants, but hostile to Catholics. The governing alliance that he built from 1854 with the “Bleus,” French-speaking conservative Catholics, strained his local powerbase, and in 1861 a section of Kingston Orangemen turned against him. In the province of Canada, the two sections were allocated the same number of seats in the Assembly. By 1860, the population of Upper Canada was surging ahead, and Confederation was partly designed to give its people a larger say in the running of the government: Ontario in 1867 received eighty-two seats, to Quebec’s sixty-five. To modern ears, that sounds like democratic fairness, but the cry for “rep. by pop.” was often a coded demand by Protestants for supremacy over Catholics.

Catholics and Protestants argued about schools, but they agreed on many issues that would be divisive today: Macdonald believed abortion “saps the very life blood of a nation” and called it a worse crime than rape. Almost everybody believed in capital punishment, that the State had the right to punish serious crimes by killing the offender. John A. Macdonald was the prime minister whose government confirmed the execution of rebel leader Louis Riel in 1885. That seems shocking: nowadays only the cruellest dictators use the death penalty to silence political opponents. But hanging was part of Macdonald’s world. Aged twenty-two, he lost a case and his client died on the gallows. As attorney general (justice minister) before Confederation and as prime minister after 1867, Macdonald approved the executions of ninety-five men and two women, mostly sentenced to death for murder. Riel’s death was controversial at the time, but we should assess Macdonald by the values of his era, not ours.

The sternly vengeful nineteenth century was surprisingly easy-going about the relations between business and the rough trade of politics. MPs received no salaries: there had to be some pay-off for taking part. Elections were violent and expensive, and serving in Parliament involved long absences in distant cities. Most politicians had business interests — hence politics was dominated by lawyers (like Macdonald himself) and merchants. They helped their ridings by boosting local companies and lobbying for public works. A candidate who could not enrich himself was reckoned too dumb to look after his riding. But there were limits: John A. Macdonald lost office in 1873 because he appeared to have sold the contract for the Pacific Railway to the Montreal magnate who had funded his election campaign the previous year. The charge was exaggerated, but it took him five years in opposition to shake it off. In the last two years of his life, the stench of corruption leaked out again: Macdonald died in office partly because he could not walk away.

“A British subject I was born,” Macdonald proclaimed in 1891; “a British subject I will die.” These sentiments of deference to a distant European homeland now seem embarrassing, as if his generation was trapped in colonial adolescence, too scared to accept grown-up nationhood. But there was hard-nosed reality in Macdonald’s rejection of Canadian independence as “all bosh.” In 1891, almost 5,000,000 Canadians lived alongside 63,000,000 Americans: Canada needed a powerful external protector to have any long-term chance of survival. Britain could not prevent an American invasion, but its mighty navy was a vengeful deterrent. Canadians needed to maintain an effective militia for local defence but, overall, it made sense to spend tax dollars on internal development, relying on the British to pay for warships. It was convenient, too, to accept a governor general sent out from “Home,” and avoid the nuisance of presidential elections. Deriving authority from the Westminster Parliament ensured legal continuity, hence the British had some say in the shaping of Confederation. However, Canadians were not subservient to Britain. Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia had enjoyed local self-government since 1848, and the new Dominion set its own priorities. British manufacturers were outraged by Macdonald’s National Policy: their taxes paid for Canada’s naval defence, but their goods could not freely enter the Canadian section of the Empire. When Macdonald said he was proud to be British, he meant that he was determined to be Canadian.

In the unique circumstances of Confederation in 1867 Canada’s first prime minister was appointed before the new Dominion’s Parliament had been elected. Impressed by Macdonald’s handling of the new constitution at meetings in London the previous winter, the British chose him for the job, elevating him above his contemporaries with the knighthood that made him Sir John A. Macdonald. To his admirers, the choice was obvious. Ontario, the largest and richest province, claimed the top job, and Macdonald was an efficient administrator and accomplished political manipulator. Unfortunately, Macdonald’s appointment was resented by George-Étienne Cartier, his Quebec ally (and rival). Go-ahead Ontario voters generally voted for Reformers (Liberals, as they gradually came to be called). Far from speaking for Canada’s largest province, as a Conservative, Macdonald belonged to a threatened species. Paradoxically, his big asset was his chief opponent, newspaper owner George Brown, a bully whose mighty Toronto Globe (now the Globe and Mail) denounced anybody who dared disagree with him. Calling himself a Liberal-Conservative, Macdonald welcomed Brown’s victims, maintaining support in his own section by constant coalition-building.

John A. Macdonald’s fondness for wordplay gives us a glimpse of how his mind worked. Once, Isabella’s sister decorated a letter with a mysterious motto, a large capital “I” followed by “2 BU.” Macdonald successfully decoded it as “I long — to be — with you.” Evidently, he would have enjoyed text messaging. He also relished puns. Adulterating sugar was a more serious crime than murder, because it was a grocer offence. The Minotaur, the monster of Greek legend, fell asleep after devouring a maiden, because of “a great lass he chewed” (lassitude!). That horror dates from around 1864, when the same brain was designing the constitution of modern Canada.

John A. Macdonald had one weakness capable of destroying his career: an alcohol problem. To this day, he is often regarded as merely a genial drunk. For two decades from 1856, he occasionally took refuge from his problems — personal, political, and financial — in binge drinking, sometimes at crisis moments in Canada’s destiny. But he was not permanently intoxicated, nor was Canada created in an alcoholic haze. Macdonald was a remarkably effective politician: as he said himself, Canadians preferred John A. drunk to George Brown sober. In the mid-1870s, he faced up to the issue and beat the bottle. His intermittent inebriation stemmed from pressures in his life that can be traced back to his childhood in Glasgow, Scotland, where he was born in 1815.