Читать книгу John A. Macdonald - Ged Martin - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

Оглавление1815–1839

I Had No Boyhood

John Alexander Macdonald was born on January 11, 1815, in Scotland’s industrial city of Glasgow. Most of its 150,000 people lived on the north bank of the Clyde, but Canada’s future prime minister was born “in one of a row of stone tenement houses,” part of a residential area south of the river — “tenement” was a Scots term for an apartment block. His parents were from the Scottish Highlands. Hugh Macdonald was a short man; Helen Shaw was both physically larger and four years older — an age gap that their son replicated in his first marriage. The couple had five children, the last born when Helen was forty. Margaret came first: “my oldest and sincerest friend,” Macdonald called her sixty years later. There were two younger siblings, James and Louisa; another boy had died in infancy. Their mother possessed a driving willpower and a lively sense of humour, both of which she greatly needed. To her son John, she transmitted a determination to succeed in life — as well as his celebrated prominent nose. Helen spoke Gaelic, but Scotland’s ancient language was associated with backwardness, and she did not to pass it on to her son.

Two contrasting stories survive from John A. Macdonald’s early days. One shows him playing to an audience. To impress other children, the four year-old placed a chair on a table, climbed up, and delivered a speech, accompanied by vehement gestures. Unluckily, he overbalanced, fell, and gashed his chin. Macdonald’s first recorded oration left him with a lifelong scar, which photo-graphers generally painted out. He was probably imitating a fiery sermon from a Presbyterian preacher. Perhaps his parents considered a Church career for him, until a schoolmaster in Canada commented that the argumentative boy would make a better lawyer than minister. The second tale reveals an introspective side of young John’s character. Taken for a walk through the busy streets, he became lost in the crowds, but was too young to explain where he lived. Eventually his father rescued him, and punished him. Such were the harsh standards of the time — and this is one of the few glimpses of Hugh in the story.

Glasgow was a boom town, heading for a bust, and Hugh Macdonald was one of the early casualties. When his small-scale textile-manufacturing enterprise failed, relatives blamed “the knavery of a partner,” but he was no businessman, and there are hints that he drank too much: John A. Macdonald’s alcohol problem was probably inherited. Financially ruined, the Macdonalds were forced to seek a new life overseas. In Helen’s complex family network, two relatives might offer support. Her brother, James Shaw, had emigrated to Georgia, while a half-sister, Anna, had married a British Army officer, Donald Macpherson, and settled at Kingston in Upper Canada. Unfortunately, the Macdonalds were not the only members of the extended family in crisis. The children of another half sister, Margaret Clark, were orphaned in 1819.

The five Clark girls were bred for genteel life, and were more likely to find suitable husbands among Southern planters than in the pioneer world of Canada. The eldest of them, Margaret, twenty-two in 1820, led three of her sisters to Georgia. One of them, Isabella, then aged eleven, later became Macdonald’s first wife. However, in childhood, she could hardly have known her five-year-old cousin well.

Another Clark daughter, Maria, fifteen in 1820, joined the Macdonalds to help rear their children, and travelled with the family to Canada. Although ten years his senior, Maria outlived Canada’s first prime minister and became the source of memories of his childhood.

Emigration was often a lottery. If the Clarks had not been orphaned, the Macdonalds might have joined Helen’s brother in Georgia (after all, Hugh knew the cotton trade). Instead of becoming a Father of Canadian Confederation, John A. might have served the Southern Confederacy, fighting to defend slavery in the American Civil War. Instead, the family headed for the Macphersons’ in Kingston. Donald Macpherson had joined the British Army back in 1775, and risen to the rank of colonel, commanding the Kingston garrison when the Americans attacked in 1812. Now retired and a respected citizen, he had recently built a suburban mansion. The Macdonalds moved into his former downtown residence.

It is hard to assess the importance of John A. Macdonald’s early childhood in Scotland. He visited relatives there on his first return trip to Britain in 1842, but rarely if ever travelled north from London on subsequent transatlantic jaunts. He was a Canadian Scot, reared among exiles. Most of his early friends were Scottish — but, later, so too were some bitter enemies. He picked up a local accent, even ending sentences with the characteristic Canadian “eh?” He once jovially remarked that although he had “the misfortune … to be a Scotchman …. I was caught young, and was brought to this country before I had been very much corrupted.” With his locker-room sense of humour, he sometimes joked about kilts. No true Scotsman would be so disrespectful.

The Macdonalds endured a squalid six-week voyage to Quebec. Packed with several hundred passengers, the Earl of Buckinghamshire was about the size of a modern Toronto Island ferry, or Vancouver’s SeaBus. Its washroom facilities were two privies, each less than fifty centimetres square, handily located over the stern. Crammed into a sleeping compartment, 1.5 metres square and stacked with bunks, were the parents, four children, cousin Maria, and Macdonald’s seventy-five-year-old grandmother, whom Helen refused to leave behind. (She barely survived the journey.) Even this cramped space was shared with another emigrant family. By the time they reached Kingston, in mid-July 1820, they had been travelling for three months.

With hindsight, emigration to Canada was John A. Macdonald’s first step towards a notable destiny. At the time, it seemed a humiliation. His parents became determined that their son must succeed to compensate for their failure. Helen in particular insisted that “John will make more than an ordinary man.” A family tragedy added to the pressures. In 1822, Macdonald’s younger brother, James, was killed in an accident — “if accident it can be called,” commented an early biographer, catching Macdonald’s anger at the tragedy even sixty years later. One evening, the parents entrusted their sons to an ex-soldier called Kennedy. Preferring boozing to babysitting, Kennedy took the children to a bar and attempted to make them drink gin. When the boys tried to run away, Kennedy lost his temper and hurled James into the iron grate of a fireplace, causing internal injuries that killed him. This appalling experience left John A. Macdonald as the sole surviving son, bearing the full weight of his parents’ hopes upon his young shoulders.

Kingston was then the largest urban centre in Upper Canada, but it contained only three thousand people, smaller than most modern country towns. New York State was just across the St. Lawrence, but the United States seemed remote — although the Macphersons vividly recalled Yankee bullets smashing into Kingston’s timber fortifications back in 1812. The British Empire, on the other hand, was a very real presence, thanks to the redcoats of the imperial garrison: the young John A. Macdonald even dreamed of a career under the British flag in India. The town had been founded in 1784 by Loyalist refugees from the newly independent American republic, families like the Hagermans and Cartwrights who had made sacrifices for Britain — and coolly expected rewards in return. Kingston’s elite accepted successful newcomers, especially Scots or Irish Protestants, men like merchant John Mowat, from Caithness, who settled in 1816; lawyer Thomas Kirkpatrick from Dublin, who arrived in 1823; and — a decade later — the medical doctor James Campbell, who came from Yorkshire via Montreal. The son of a failed immigrant, John A. Macdonald had to gatecrash this local elite. For all his fabled political charm, his sometimes fraught relations with Kingston’s leading families reflected his marginal status.

After failing to establish a store in Kingston, Hugh Macdonald shifted forty kilometres west to the village of Hay Bay in 1824. Later, he moved to the Stone Mills (now Glenora) in Prince Edward County, to run the flour mill that gave the place its name. Although Hugh had no farming experience, he considered moving still further west, to try growing wheat. A neighbour tactfully steered him away from the project: nothing would grow beyond Port Hope because “the summer frosts kill everything.” Decades later, Macdonald quoted that story against pessimists who doubted the potential of the prairies. In 1836, the Macphersons arranged a job for Hugh as a clerk in the Commercial Bank, Kingston’s own financial institution, and the Macdonalds moved back to town. By then, his son had replaced him as the family breadwinner. Hugh, it was discreetly recalled, was “unequal to the responsibilities of the head of a family.” John A. recalled that it had been his indomitable mother who carried them through the difficult early years in Canada.

John A. Macdonald was a bright child, “the star of Canada,” as one of Hugh’s drinking pals called him. Aged ten in 1825, he was sent to the Midland District Grammar School in Kingston, an academy that specialized in teaching Latin and mathematics, subjects which were the key to professional or commercial careers. (The school was less effective at teaching French, a language Macdonald never mastered.) For five years he shuttled between the town and his family home in the country, living in both, belonging to neither. This strange phase of his life would emphasize the dual aspect of his character — the competitive and secretive personality who manipulated charm to win friends. In Kingston, he lodged with a miserly landlady, spending his free time cadging food from the Macphersons. The genial old colonel became an alternative father figure. Donald Macpherson had risen from the ranks to defend Canada for the Empire in the War of 1812; John A. Macdonald would replicate his gallant career in politics.

In class, the son of a struggling country storekeeper competed with the sons of the comfortable local elite, who likely looked down on him. Opening a gymnasium in Ottawa sixty years later, Macdonald joked “when I was a boy at school I was fighting all the time, but I always got licked.” He continued to be a star pupil, the boy the headmaster would summon to the blackboard to impress visitors with the school’s mathematical teaching. But the unending pressure to succeed took its toll. Once, facing stressful examinations, young Macdonald ran away from school, arriving home unexpectedly, and close to a breakdown. He paid a high price for his elite schooling. “I had no boyhood,” he once said in later years.

In the holidays, Macdonald imitated Colonel Macpherson by playing soldiers with his sisters, casting himself as their commander. Once, when Louisa ignored orders, he picked up a real gun and threatened to shoot her for disobedience. Fortunately, Margaret dissuaded him, for the weapon was loaded. She probably saved Macdonald’s political career: a slaughtered sister would have been an electoral liability. Campaigning in the area sixty years later, Macdonald spoke nostalgically of idyllic days when he had run wild and barefoot, but in fact he did not belong around Hay Bay and Glenora any more than he did in town. His parents’ well-meaning gesture of inviting local children to parties to welcome John home from school probably accentuated resentment against the “big-nosed Scotch kid.” The girls mocked him as “ugly John”; the boys bullied him. One winter, Macdonald tried skating on Lake Ontario. Sneering at his spindly legs, a local lad upended him on the ice. On another occasion, a bigger boy pinned him down and rubbed Hugh Macdonald’s flour into his untidy black hair. For their part, the country children considered the interloper to be vindictive and violent-tempered.

“From the age of fifteen I began to earn my own living,” John A. Macdonald once recalled, bemoaning his lost boyhood. But in pioneer days, most youngsters worked by their mid-teens, and his puzzling comment suggests that he had bigger expectations. As prime minister, he remarked that if he had received a university education, he would have made his career in literature. Perhaps this was just political image-making, but maybe his hothouse schooling was intended as a preparation for a college education. If so, the idea must have been to send him to Scotland, where universities accepted students in their mid-teens: planned colleges in Montreal and Toronto had yet to open their doors. A dream of higher education in Scotland might also explain why, in 1829, John was switched to a new Kingston academy, opened by a young Aberdeen University graduate. One other clue is revealing. In 1839, Macdonald was scheduled to speak at a fund-raising meeting in Kingston, part of the campaign to establish Queen’s University. He prepared an address on the importance of education but, when his turn came, he could not utter a word. It was John A. Macdonald’s only failure as a public speaker: the subject evidently triggered complex emotions. The dashing of his hopes for a university education perhaps helps explain John A. Macdonald’s drive to succeed in life.

In 1830, Macdonald entered the Kingston law office of George Mackenzie, and also lodged in his house. A kindly couple with no children of their own, the Mackenzies gave their charge some space to manage his life. Like many adolescents, Macdonald disliked getting up in the mornings. One day, unable to rouse him, Sarah Mackenzie closed off every chink of light in the lad’s bedroom and left him comatose in pitch darkness. When he eventually shook himself awake and opened the curtains, the sun was setting. The problem did not recur.

Young Macdonald’s sharp intelligence and a photographic memory impressed his boss and, late in 1832, Mackenzie sent him to manage a branch law office at Napanee, forty kilometres west of Kingston. Not quite eighteen and operating independently for the first time, Macdonald had to choose the personality he wished to project. Initially, he wrapped himself in professional dignity, perhaps emulating his father’s prickly concern for status. Mackenzie criticized his “dead & alive” pomposity. “I do not think you are so free & lively with the people as a young man eager for their good will should be.” John A. Macdonald kept that letter, which contained some of the best advice he ever received. He would become another George Mackenzie, not a second Hugh Macdonald.

At the end of 1833, another opportunity presented itself. His lawyer cousin Lowther Pennington Macpherson — the old colonel’s son — was dying of a lung disease, and under medical advice to escape the Canadian winter. Macpherson needed Macdonald to run his law office at Hallowell, in Prince Edward County. George Mackenzie graciously released him, and Macdonald found himself ten kilometres from the family home at Glenora. But was Hallowell an opportunity or a trap? Macpherson reported August 1834 that his cough was worse. “God only knows how it is to terminate.” Cousin Lowther would never return, but John A. Macdonald had no wish to be consigned to a country backwater.

Even in the 1830s, Hallowell was overshadowed by its neighbour, Picton. The young man appreciatively remembered as a “poor and friendless boy” supported a campaign to merge the two communities under a neutral name, Port William, in honour of King William IV. John A. Macdonald’s first attempt at a negotiated union under the symbolic headship of the British Crown was a failure: ambitious Picton simply swallowed up its neighbour. Thirty years later, Macdonald successfully led a second such project, Confederation, on a continental scale. At Hallowell, Macdonald took his first steps in community activity, helping to found a debating club, and serving as secretary of the local school board. Keen to keep him in town, local businessmen reportedly offered to finance him in his own law practice, but his ambitions lay elsewhere.

John A. Macdonald seemed on track to becoming George Mackenzie’s junior partner. Mackenzie was planning a political career and would need a trusted lieutenant to manage his law office and his election campaigns in Kingston. Rejecting the political polarization which later provoked the 1837 rebellions, Mackenzie sought the middle ground, advocating precisely the moderate Conservatism that Macdonald himself later championed. But the partnership never happened. In August 1834, cholera swept across Canada. The terrifying disease could kill within forty-eight hours and George Mackenzie was one of its victims. For John A. Macdonald, it was suddenly important to return to Kingston and inherit Mackenzie’s clients. His motivation was not entirely cynical. The back roads of rural Canada were notoriously bad, and travel through country districts was only possible on horseback. Macdonald tried it — and fell, breaking his arm. In Kingston, lawyers sat in comfortable offices and waited for clients to come to them. Macdonald redoubled his efforts to qualify, and we have a glimpse of him sitting under a willow tree in a Hallowell garden, “studying intently” while small boys played leap-frog around him. He passed his examinations and, in August 1835, set up in business as an attorney in a cross-street off Kingston’s central business district.

There is a mystery here. Born in January 1815, Macdonald was twenty when he opened his first law office — but the minimum age to practise was twenty-one. His birth had been formally recorded, in distant Edinburgh, but Canada had no registration system. Apparently, John A.’s father agreed to counter-sign a statement backdating his birth by twelve months: in later years, the year of his birth was often given as 1814. It seems the first formal act of John A. Macdonald’s legal career was to commit perjury — a harbinger of his ruthless readiness to cut corners in later life.

The young adult John A. Macdonald was “slender, with a marked disinclination to corpulency.” Even in his seventies, leading a sedentary life as prime minister, his weight just topped eighty kilograms (180 pounds or under thirteen stone) — light enough for someone who was five feet, eleven inches (180 centimetres) tall — well above the average of the time. But he did not use his height to overawe. Macdonald had a slight stoop, an inclusive gesture that put people at ease. James Porter, a Picton acquaintance, recalled spotting him on the streets of Kingston whenever he visited the town — and was flattered to be affably recognized: “he wouldn’t wait for me to come and speak, but he would duck his head in that peculiar way of his, and come right across the street to shake hands.” The greeting was informal, man-to-man: “Damn it, Porter, are you alive yet?” Macdonald claimed that he forgot only one face in a thousand, and his impressive memory for people he had only met briefly would win him devotees across Canada. He had absorbed George Mackenzie’s advice to loosen up: “no client, however poor, ever came out of Mr. Macdonald’s office complaining of snobbery.”

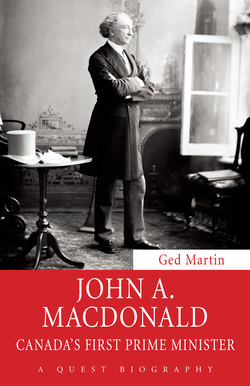

His giant nose and unruly black hair contributed to an unforgettable face, but not a pretty one. When Louisa was congratulated on resembling her famous brother, she indignantly commented that he was the ugliest man in Canada. It was a face full of character, manipulated by “a consummate actor,” with “a strong desire to please,” who could easily “assume the role of the intensely interested recipient.” In the early years of slow-exposure photography, sitters had to remain motionless for lengthy periods. Hence most nineteenth-century politicians glare at us, pop-eyed with tension. But even the earliest photographs of John A. Macdonald convey a lively, genial personality: one of his theatrical skills was his ability to hold a pose. Yet he was not merely playing a role. Macdonald’s “wit and his inexhaustible fund of anecdote” infused every gathering that he attended. One critic remembered prime-ministerial dinner parties, where Macdonald carried on a serious conversation at one end of the table, while “telling risqué anecdotes to the guests at the other end.”

As James Porter recalled, “there wasn’t much fun that John A. wasn’t up to.” At Picton, he formed a mock order of chivalry, la Société de la Vache Rouge (Knights of the Red Cow). One Christmas, Macdonald brought the Knights to Glenora for the ceremonial enthronement of his mother as patroness, a paper knife serving as her sword of office. As master of ceremonies, John A. wisecracked his way through the proceedings until tears of laughter ran down Helen’s face. “God help us for a set of fools!” she exclaimed. Years later, Macdonald told an astonished British statesman about an American vacation he had taken with two friends, in which they pretended to be strolling players. Calling at taverns, Macdonald played tunes, one of his companions pretended to be a dancing bear while the third collected coins from onlookers.

Macdonald enjoyed irresponsible pranks. On summer night in Kingston, he led a group of friends in bricking up old Jemmy Williamson’s doorway, a stunt requiring a couple of hours of silent labour. From a hiding place, they threw pebbles at the bedroom window until Williamson came downstairs to investigate. A solemn Scotsman who believed in Hellfire religion, he thought he had been walled in as a punishment for his sins. An earlier joke was even less amusing. A Picton hotelier was notorious for driving his buggy at daredevil speed through the town. One night Macdonald slowed him down by building a barrier across the darkened street. The victim escaped unhurt, but his buggy was damaged and the horse badly injured. Worse still, suspicion fell on an innocent man: Macdonald confessed, but managed to get the affair hushed up. He was less fortunate when an altercation with a local doctor came to court, although the assault charge against him failed: punches had been thrown when the medical gentleman had dismissed the young law clerk as a “lousy Scotchman.”

Macdonald was also engaged in serious activity in the adult world. He was elected to a junior office in Kingston’s Celtic Society, with twice-yearly banquets including toasts damning Canada’s “external and internal enemies” (Americans and radicals) and praising “the immortal memory” of James Wolfe, conqueror of Quebec. This organization embodied an important Scots network, from which he recruited his first law pupil, Oliver Mowat, son of a prominent merchant, magistrate, and Presbyterian Church elder. The two were active members of the Kingston Young Men’s Society — Macdonald was president in 1837 — which debated political and religious questions. In 1836, he had voted in his first election, helping the Tory John S. Cartwright to defeat the Reformers in the nearby riding of Lennox and Addington.

John A. Macdonald’s political opinions were formed in a highly confrontational period of Canadian history. “Tory” was the shorthand for Conservatives, while, after Confederation, Ontario Reformers adopted the name of their French-Canadian allies, le parti libéral, to become the Liberal Party of Canada. An election pitting Tory-Conservatives against Liberal-Reformers sounds familiar to modern Canadians, but the outward two-party system masked four political streams, two on each side, usually forming uneasy alliances. The extreme Tories believed in privilege, so long as it was privilege for themselves. However, they were a tiny minority (hence their nickname, the “Family Compact”) who needed the votes of more moderate Conservatives, people like John A. Macdonald who supported British institutions and the development of Canada’s economy. “I could never have been called a Tory,” he later recalled, mocking “old fogy Toryism.”

Their opponents were split too. Moderate Reformers admired Britain’s system of parliamentary government, and wished to adapt it to enable Canadians to run their own affairs through a miniature copy of the Westminster Parliament — a system known as “responsible government.” They were uncomfortable allies of the radicals, who admired American-style elective institutions, and sometimes sought to defy the Empire and join the United States. Two-party politics in Canada operated more like a four-cornered boxing match, with some of the sharpest political struggles happening, not between, but within, the main groupings. However, as divisive issues were resolved, such as the achievement of responsible government, moderates on both sides found more in common with their erstwhile opponents than with their quarrelsome friends — a strategy that John A. Macdonald exploited to occupy the middle ground in politics for two decades after 1854.

Unfortunately, this subtlety was lost on the governor of Upper Canada, Sir Francis Head, an eccentric British Army officer who naively believed that anyone who opposed his Tory supporters must be a Republican traitor. Governor Head enlivened the 1836 campaign by issuing colourful appeals to vote for the Union Jack. With the right to vote confined to property-owning British subjects, barely a fifth of adult males qualified (and no women). It was alleged that in 1836, veteran Reformers were thrown off the electoral rolls on shabby pretexts, while normally sleepy bureaucrats rushed out title deeds to government supporters — which was probably how young Macdonald acquired the hundred acres of wild land that entitled him to vote. Predictably, the Reformers were routed. Fifty-five years later, in his last desperate election campaign of 1891, Sir John A. Macdonald would resort to the same unsavoury combination of flag-waving and manipulation of voter rolls.

Head’s election victory was overkill. The big losers in 1836 were the moderate Reformers, their strategy of patient argument shown to be powerless against Tory arrogance. The vacuum of opposition was filled by radicals with their big talk of fighting for liberty. As mayor of York, journalist William Lyon Mackenzie had proved a decisive administrator, even changing the name of Kingston’s burgeoning rival to Toronto. But in futile opposition, his newspaper became increasingly reckless. With the British authorities struggling to suppress a national uprising in French Canada, Mackenzie’s inflammatory language fanned rebellion among his supporters, in the hinterland of Toronto. December 1837 became one of the most traumatic months in John A. Macdonald’s life.

The crisis of that month was not just political but professional and personal. Macdonald had quickly acquired a reputation as a clever courtroom performer, who could talk to juries of working men in language they understood. Once he described an assault by saying the defendant “took & went & hit him a brick.” Few cases were as daunting as that of William Brass, an alcoholic hobo charged in 1837 with raping an eight-year-old girl, a crime that carried the death penalty. Although Macdonald was praised for his “ingenious” defence, it was perhaps too clever. His first line of argument, that Brass had been too drunk to commit a sexual act, collapsed when the victim gave harrowing testimony. The young lawyer’s fallback position, that his client’s alcohol problem was a form of insanity, also failed. Despite Macdonald’s “very able” performance, Brass was found guilty and sentenced to die. His execution, on December 1, 1837, was horribly bungled. Brass was publicly hanged, from an upstairs window of Kingston’s courthouse. The executioner miscalculated the length of the rope, and Brass crashed into his own coffin. Despite pleading that his escape was proof of his innocence, he was dragged back upstairs and choked to death on a shortened noose. We can only guess the impact of this failure on the twenty-two year-old Macdonald, whose client was widely believed to be the victim of a frame-up. A decade later, Macdonald became a political ally of W.H. Draper, who had prosecuted Brass. Draper occasionally teased the younger man, reminding Macdonald that he was such a smart lawyer that his client had been hanged. Bricking up Jemmy Williamson’s front door was a huge joke, but losing a court case could send a man to a hideous death.

Within a week, John A. Macdonald was facing death himself. He had travelled to Toronto, probably on legal business, but perhaps carrying a last-ditch plea to save Brass. News of insurrection in Lower Canada encouraged William Lyon Mackenzie to attempt to seize the Upper Canada capital. The first blood was shed on December 4, 1837. Three days later, a thousand-strong government force marched up Yonge Street to attack the rebel headquarters at Montgomery’s Tavern. The militia outnumbered the insurgents, and they had the advantage of two big guns. A few shells fired at the tavern proved enough to rout Mackenzie’s untrained followers.

Marching close to the front of the column, just behind the two cannon, was John A. Macdonald. “I carried my musket in ’37,” he would say in later years, laconically telling Parliament in 1884: “I suppose I fought as bravely as my confreres.” Yet he was reluctant to talk about that day when he had gone into battle. His close friend, J.R. Gowan, only discovered that they had been comrades in arms at Montgomery’s while reminiscing on the fiftieth anniversary of the armed clash. John A. Macdonald took part, not because he had volunteered, but because all adult males had a duty to serve in the militia. They were called out for a few days of basic training each summer, but they were definitely not disciplined soldiers programmed to stand and fight. Because there were few casualties in that brief skirmish, historians rather belittle the episode. Yet it was a frightening experience for men who had never been under fire: Gowan recalled his “strong inclination to run away.”

Because Macdonald hardly mentioned his experience, the 1837 episode has never been factored into his life story. It is noteworthy that he took part, and significant that he never boasted about it: a Conservative politician might have proclaimed that he had risked his life to preserve Canada for Queen Victoria. John A. Macdonald is often caricatured as an amoral and unprincipled operator, who struck deals and cut corners. But we should see him as somebody who knew that Canadian society was fragile, who had learned that the art of government involved avoiding conflict among its contrasting elements — Tories and radicals, Catholics and Protestants, English and French. As he put it in 1854, Canadians should “agree as much as possible” and that meant “respecting each other’s principles ... even each other’s prejudices. Unless they were governed by a spirit of compromise and kindly feelings towards each other, they could never get on harmoniously together.” In a rare allusion to those traumatic events, in 1887 he called the rebellion era “days of humiliation,” adding that “we can all look back and respect the men who fought on one side or the other, for we know there was a feeling of right and justice on both sides.” The clash at Montgomery’s had been part of “a war of fellow-subject against fellow-subject” which he preferred to forget — but, throughout his career, he remembered the lessons of 1837.

Macdonald was angry with the authorities for provoking the conflict. He curtly refused promotion in the militia, and boldly defended victims of the Tory crackdown on dissidents, showing a courageous commitment to fair play in the heated post-rebellion atmosphere. Eight Reformers from the Kingston area were charged with treason on dubious evidence; in 1885, as he pondered the case of Louis Riel, he recalled how he had “tripped up” the prosecution to secure their acquittal. A further fifteen prisoners decamped from military custody. In angry over-reaction, the garrison commander, Colonel Henry Dundas, concluded the storekeeper, Reformer John Ashley, must have connived in their escape. Embarrassed local magistrates quickly released Ashley from jail, but the irate victim hired John A. Macdonald to sue for wrongful arrest. This was courtroom drama, for Dundas, the heir to a peerage, would one day sit in the House of Lords — too elevated a personage to answer to an angry storekeeper and a raw young barrister. Army officers called to give evidence found themselves roughly cross-examined. The judge summed up in the colonel’s favour, but the jury shocked respectable Kingston opinion and awarded Ashley $800 — huge damages for the time. For years afterwards, the outraged officers of the garrison displayed the ultimate disapproval of English gentlemen by refusing to invite Macdonald to dinner, “but John A. cared nothing for that.”

Although internal rebellion had collapsed, Canada remained under external threat. In mid-November, a paramilitary force from the United States landed at Prescott, one hundred kilometres downriver from Kingston. They were counter-attacked by British regulars, disciplined soldiers who stood firm and shot straight. By the time the invaders surrendered, there were several dozen fatalities. The prisoners were taken to Kingston, where one local resident was appalled to discover that his own brother-in-law was among those captured. After two senior lawyers refused to help, he implored John A. Macdonald to provide a defence. There was little the young lawyer could do: the invaders were tried by court martial, and the resentful military refused to recognize the upstart lawyer who had humiliated their commanding officer. A grisly batch of hangings ensued, and Macdonald was called to death row, to draw up the bandit leader’s will as he awaited the gallows.

“Macdonald’s popularity was terribly strained by his defence of these men.” But John A. Macdonald was playing for higher stakes than popularity. He was putting down a marker: the elite must accept him, and on his own terms. For their part, the city’s power brokers decided to recruit him. Increasingly challenged by Toronto, Kingston needed to maximize its local talent. In June 1839, John A. Macdonald became a director of the Commercial Bank — the institution where his father worked as a clerk.

That autumn, the death of Kingston’s mayor, Henry Cassady, provided further opportunities. Cassady’s legal apprentice,

seventeen-year-old Alexander Campbell — like Oliver Mowat, offspring of the local elite — transferred to Macdonald’s tutelage in October 1839. At intervals through the next fifty years, Campbell would act as Macdonald’s business partner, campaign manager, and political lieutenant, usually dazzled but occasionally horrified by the activities of his magnetic mentor. Mowat soon moved to Toronto, but Campbell remained the workhorse who could handle groups who sometimes distrusted John A. — from genteel Tories to intolerant Orangemen. Macdonald also succeeded Cassady as the Commercial Bank’s official legal adviser, a position previously held by George Mackenzie. At the age of twenty-four, John A. Macdonald could now shift his focus away from fee-grubbing courtroom work towards the attractive world of business and corporate law. He was no longer “poor and friendless.” Hothouse schooling, grinding apprenticeship, plus ability, determination, and charm had won him a seat at Kingston’s top table. He was almost one third of his journey through life. Now he could map out how he planned to live the rest.