Читать книгу Comedy Writing Self-Taught Workbook - Gene Perret - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеExercise 1

Collect Fifty Great One-Liners

You just read how we want you to write and the purpose of this book is to get you to write. Now we are on to our first exercise and guess what? We don’t want you to write.

Your first assignment is to collect fifty great one-liners. These should be jokes that in your opinion are above all others. Not just lines that make you laugh, but ones that make you say, “I wish I had written that.”

Even though you won’t be writing right now, this exercise is important. If you were building a house, you wouldn’t just start nailing walls together. First you would need to lay the foundation. But even before the foundation you would need to do some groundwork. You need to decide what style of house you are going to build. Will it be one story or two? What will it look like? You need to draw up plans. Consider this exercise the blueprints for your future writing.

You may be saying to yourself, “Can’t you just give me a list of great jokes to use?” The easy answer is yes, but then you would miss out on the benefits of this assignment. Also you would have a list that was geared toward us and not one that is your own.

There are a number of benefits to tackling this assignment and devoting care to it. Don’t just pick the first fifty lines that make you laugh. There is a difference between enjoying a comedy performance and analyzing it. We want you to do the latter. Look at the material with a critical eye—at least while doing this assignment. Afterward you can go back to just enjoying the humor. Watch all kinds of comedy—young comedians, old comedians, newcomers, and seasoned professionals. Record some comics on TV as well as go to a few live performances. Read various joke books. Immerse yourself in comedy and capture the lines that really stand out.

You may not realize it while you are doing this, but you are actually learning quite a bit about comedy. You are focusing on it and absorbing it. You are learning what makes you laugh. You’ll start to pick up on the different styles of comedy and develop an awareness of what kind of comedy you prefer. You may find you like the rapid-fire one-liners of the old-time comics or you may prefer a storytelling type of delivery.

Your list will provide you with a database of great material to refer to when you need inspiration. If you were a painter, would you like to paint like Van Gogh or your eighth-grade art teacher? You want to strive to be the best. And your list will do that for you—consider it your very own Comedy Louvre. Anytime you like, you can relish in or surround yourself with the great lines that you want to produce. Surrounding yourself with great comedy can inspire you to write the same.

This is a valuable tool when you are hit with writer’s block. At one time or another we all struggle with that blank sheet of paper. When that happens, take a gander at your list. See what has been done and know that you can do it, too. Use these lines to springboard new ideas.

Most likely your list will contain jokes that use different formulas and styles that you can draw from when generating your own material. Your list may have a “series-of-three joke,” a “definition joke,” and so on. Whatever you are working on, try generating the same style of joke, that is, a series of three, a definition, and so on. It gives you a starting point to generate material on a given topic.

Your list can also be used as a comparison for your own writing. Sometimes we write a line and know it has all the makings of a great joke, but it just isn’t great yet. Compare it to the lines that are on your list. What do they have that your line is missing? Or what have they cut out that you are including? Use the great lines to influence your own material.

So start collecting. Look for great gags. Keep the list going. Whenever you hear a great line, jot it down.

Oh yeah, this may be a good place to mention that if you wrote a joke that you think is superb, put it on the list. We don’t want any false modesty. If the joke is great, it deserves to be on your list. Seeing your own line among other great lines can be the best encouragement of all.

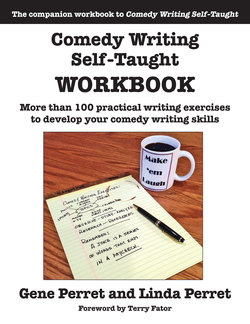

This exercise is also in the companion book, Comedy Writing Self-Taught. We felt it was important enough to include here. However, if you completed this exercise while reading the other volume, there’s no need to repeat it here . . . unless, of course, you want to.

Get ready, though, because now we are going to get you writing.

Exercise 2

Captioning

Cartoons are an excellent starting point for learning to write solid one-liners. Cartoons consist of a drawing and a funny caption. Of course, some are captionless, but we’ll concentrate on those that have a word joke attached. The drawing provides the situation and the caption provides the humor. That’s a similar structure for many one-liners.

Studying cartoon humor is a good basis for teaching yourself to write effective humor. Cartoons are visual. They’re drawings so they must be a drawing of something. The image is an integral part of the comedy. Sometimes it’s easy for us to overlook the value of the visual in verbal comedy. But it’s often the image that the word joke presents to the minds of the listeners that gives the gag added impact. A vivid picture painted in the audience’s mind gives a boost to the joke’s effectiveness.

Also, cartoons prepare the reader for laughter. Cartoons should be funny. Otherwise, why would they be published in the paper or magazine? When a reader sees a cartoon drawing, he or she is predisposed to being entertained. A good, solid oneliner should prepare the listener for the laugh to come. It should time the punchline for the maximum effect. It’s a lesson well learned from cartoons.

You’ll begin teaching yourself to write good stand-up material by learning the mechanics of writing captions for cartoons.

For this exercise, begin collecting good cartoons from magazines or papers. Gather at least ten or twelve funny cartoons. Either cut them out and paste them on paper or scan them and print them out. Save them one way or another.

Each cartoon will have a caption affixed to it. It should be a good caption, too. You don’t want to collect weak ones. You want solid ones. So the first benefit of this exercise is that you will have a few laughs.

But you’ll have even more laughs as you work your way through this exercise. You’re now going to create several alternate lines for each cartoon that you’ve gathered. These new lines can be variations on the original cartoon caption, or you can take the drawing in an entirely new direction and generate a funny caption that has no relation whatsoever to the one that was published.

As a humorist, you’re certainly going to try to “outfunny” the cartoonist. However, since the original was bought and printed, it’s probably pretty effective. Sure, you should try to “top” it, but even if you don’t, you’ll gain some valuable lessons from this exercise in writing comedy.

Exercise 3

A Little Tougher Captioning

This exercise is similar to the previous one. However, it’s probably going to be a little tougher. You may find that to be true throughout this exercise book, but that’s how you develop skills. If you take violin lessons, your first practice piece will probably be an easy one. But as you progress, the music will become more complex and the lessons a bit more challenging to master. So as the writing exercises become more demanding, you will realize that your knowledge and skills are growing.

In the previous exercise, the caption was included with the cartoon. That provided a direction for the humor. You could use that “slant” to create your new captions. Or you could have, as we suggested, taken the humor into a whole different area. But in either case you had something to start with.

In this exercise, you won’t have that luxury.

Here, you should have a friend do your research for you. Ask this associate to cut out ten to fifteen cartoons from the newspaper or magazine and remove the caption from each one. If you’re terribly disciplined and promise yourself that you won’t cheat, you can select the cartoons yourself. But be sure to cover the caption before you snip the cartoon from the paper. You should not have any idea what the original caption said.

Now, of course, you will provide the funny caption for each drawing. It may be wise to write several so that you can select the best.

If it’s possible and your associate will cooperate, you may try to save the original captions so that when you’re done, you can compare your work to the original. But that’s a bonus of this lesson.

Just writing a brilliantly funny caption should be reward enough.

Exercise 4

Captioning Words

Now that you’ve had some fun with cartoons, you’re going to teach yourself how to use the captioning technique in writing verbal humor. A cartoon, as we noted, is a drawing with a joke attached to it. A one-liner often is a factual statement with a joke attached to it. It’s a straight line and a punchline. It’s similar to the cartoon structure.

Consider these lines about presidents that Bob Hope used:

Harry Truman ruled the country with an iron fist. The same way he played the piano.

Eisenhower switched hobbies from golf to painting. It was fewer strokes.

Ronald Reagan is one politician who never lied, cheated, or stole. He always had an agent who did that for him.

Notice they all start with a factual statement. It’s not funny; it’s simply there. The joke happens when you attach the punchline to it. In effect, you’re putting a caption on a statement.

For this exercise, that’s exactly what you’re going to do. Find a news item in a paper or a magazine. It can be in any area—politics, sports, entertainment, human interest, a goofy news item, anything. Read through the item and underline or make notes on several factual items. They needn’t be funny; in fact, it’s probably better if they’re not. Remember, many of the drawings in cartoons are not inherently funny.

Jot down a series of these factual items—somewhere between six and ten of them. They are now your straight lines. Attach a caption, or a punchline, to each of them. It’s not a bad idea to write several alternate punchlines for each.

By doing this, you’ve converted straight lines to jokes by attaching a punchline.

It’s a procedure you will use frequently as a professional joke writer.

Also, once you finish this exercise, you can repeat it often. All you need are different news items or topics.

Exercise 5

Gathering References

“References” are an important part of comedy writing. They refer to either your main topic, your punchline, or both. Often they can help create gags by combining ideas that are otherwise seemingly unrelated.

I’m sure you’ve heard the question “What’s black and white and red all over?” The classic answer is “a newspaper.” This line refers to something that is black and white (a newspaper) and to something that is red. The punchline uses a play on words—“read” for “red.”

But “a newspaper” is not the only punchline. You can uncover other references. Something “black and white and red all over” could be a wounded nun . . . an embarrassed convict . . . a zebra with diaper rash. Even these are just the tip of the iceberg.

And that’s what we want you to work on—uncovering more of that iceberg. Come up with fifteen to twenty additional answers to the question “What is black and white and red all over.”

To begin, make a list of references—anything you can think of that is black and white. Your list may include penguins, Oreo cookies, referees, and so on. Now go back and do the exact same thing for items that are red—sunburn, velvet cake, Lucille Ball’s hair. Keep going with your lists. Get creative. Don’t edit or limit yourself at this point. Get it down on paper. You can always remove or modify later as needed.

Pull one item from the black and white list—maybe a penguin. Now look over your list of red things. What is on that list that might work in this situation? Hmm . . . a sunburn? Now you have your line. What’s black and white and red all over? A sunburned penguin.

You may be able to play with the line even more and find a way to imply the red without coming out directly and saying it. Look at the example we gave earlier of the nun. We never mentioned blood. But you came to that conclusion with the word “wounded.”

Don’t be afraid to push the envelope a bit and get a little zany. Have fun with it. But be warned, it can be addictive. You’ll be thinking of things that are black and white and red all over for a long time, and that’s good. In doing this you’ll be learning and developing one of the fundamentals of comedy writing—finding references.

Exercise 6

In the News

Comedy writers need to keep up on what’s happening in the news and what people are talking about. Using current events and references helps to keep our material fresh and on the spot. Newsworthy items can also be a source of topics, and that’s what we are going to work on now.

Pick up a newspaper or go to a news website and read through it. Find an article that intrigues you. It can be from the front page or sports or entertainment section – in fact, it can be from any area of the newspaper or website. It doesn’t have to be long—just something that catches your attention and would be of interest to others.

Now read the article thoroughly. It is a good idea to keep the article handy because as we progress with this exercise, you may want to refer back to it. If you are reading the article online, we recommend printing it out. Sometimes when you go back to look it up, the article has been removed. Most likely you can find it again, but it takes time and can be detrimental to the creative process. So plan ahead and keep the article at the ready.

OK, we strayed a bit so now back to work. When you have a good idea of what the article is about, start asking yourself some questions about it. Questions that prompt a funny response or at least help you to create gags may look like these:

•Who is affected by this?

•Who is happy about this?

•Who is upset about this?

•What would happen if this happened in a different point in history?

•Will it affect everyday life?

•Will it affect my wallet?

•What changes will take place because of this?

•How will it affect the future?

•Will there be long-term effects?

•What would famous people think about this?

•What would the Average Joe say about it?

These are just our questions. They are fairly generic. Your list may include some of these questions, may be completely different, or pertain only to your selected article.

It’s a good idea to write your questions down or keep them in your computer. That way you have a ready-made list for the next time. You can change, alter, add, or delete as needed for your new assignment. Asking and answering questions can often provide the impetus that jars joke ideas out of your imagination.

As an example, let’s say your local paper published an article about the public library closing due to budget cuts (these small-town presses are a gold mine for comedy ideas). You interview yourself with the questions you generated. One question is “What would happen if the library closed at a different point in history?” This may cause you to think of Ben Franklin, who formed the first library. Based on that idea, you may come up with the line:

Ben Franklin said, “If I knew today’s politicians were going to be so irresponsible, I never would have invented the darn thing in the first place.”

This gives you an idea. Now you do it, using the article you picked out earlier and the list of questions you created. Write twenty jokes that are based on your article and answer the questions in a funny way.

Exercise 7

Turn Ideas into Jokes

Every joke has a concept or, in other words, the thought the joke conveys. This aspect of a joke is important, but it’s not the only component. The wording of a gag is also essential.

In fact, it is the phrasing that transforms a comedy idea into a joke. Let’s take a look at this funny idea:

My wife talks a lot.

The idea has humor, but it isn’t a joke—yet. It’s the thought behind the joke. Now let’s look at the way Henny Youngman conveyed this idea:

I didn’t talk to my wife for three weeks. I didn’t want to interrupt.

Henny made it a joke. It went from a funny thought into a full-fledged, fleshed-out gag.

The phrasing of a joke can be tricky. You need to give enough information to your listeners so that they understand what you are saying, but not so much that the audience loses interest.

Using the classic Henny Youngman line above, notice how there is no mention that his wife talks a lot. The wording of the line implies that. What if Mr. Youngman had said, “My wife talks so much. For three weeks I never got to say anything.”

The concepts are the same, but one is a great joke and the other . . . well . . . isn’t.

The following is a list of twelve comedy concepts. There’s humor behind them, but at this stage they aren’t jokes. Your job is to take each sentence and transform it into a joke.

•Whatever line I get in always moves the slowest.

•My wife spends so much, I hope her credit card gets stolen.

•Gas is so expensive, I have to find different ways to afford it.

•Women hate it when men watch football.

•Men hate it when women watch figure skating.

•How much we depend on electricity.

•Every device manufactured now has a clock built into it.

•What used to be “courtship” is now considered “criminal activity.”

•Smoking has become unattractive.

•Ways to prove that dog is man’s best friend . . . or not.

•How much Las Vegas casinos love people with “a system.”

•Money can’t buy friendship.

You can repeat this exercise many times by coming up with some concepts on your own. Or for more of a challenge, have a friend generate them for you. Now take these ideas and turn them into funny lines.

Exercise 8

The Almost Right Word

Obviously, words are important to any writer. Good writers search not only for the correct word but for the precisely accurate word. Mark Twain once said, “The difference between the almost right word and the right word is the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning.” Someone later wrote a variation: “The difference between the right word and the almost right word is like the difference between ‘chicken’ and ‘chicken pox.’”

So serious writers are intent on finding the “no-other-word-will-do” word. In joke writing, it’s imperative to use accurate, descriptive words. However, sometimes comedy writers call on their creativity to find the precise wrong word to use in place of the exact right word.

In 1775 Richard Brinsley Sheridan wrote a play called The Rivals. One of the characters was Mrs. Malaprop, who was noted for misusing the English language. Throughout the play she would inadvertently use the wrong word. For instance, she said of another character, “She’s as headstrong as an allegory on the Nile.” She meant, of course, “alligator on the Nile.”

These have since become known as “malapropisms” or “malaprops” and can be used to great effect for comedy. Leo Gorcey, who played the unofficial leader of the gang in the Dead End Kids movies, mangled the language masterfully. When he had a brilliant thought, he’d boast, “I’ve just come up with a brilliant seduction.” If he interrupted a conversation, he would say, “Forgive my protrusion.”

At a roast you may hear a speaker say:

I have been seated next to our guest of honor at this banquet and I can tell you now that he is a man of great perspiration.

Often the wrong word can also paint a graphic picture that adds to the comedy. For example, this line from Archie Bunker:

Edith is not here right now. She’s had to visit her groinacologist.

Or the tycoon in poor health who said:

I’d like to leave you now with my last will and testicle.

That’s the idea behind this exercise. We’d like you to generate about fifteen to twenty malaprops. Make them as colorful and graphic as you can. This exercise may require even more creativity than finding the appropriate language, but it will pay benefits in teaching you to write comedy. It’s ironic that aggressively searching for the wrong word provides priceless experience in finding the right word. That’s valuable training for anyone, especially a comedy writer

And it’s great fun, so enjoy this exercise.

Exercise 9

It’s All Around Us

One stumbling block beginning comedy writers face is that “there’s nothing to write about.” Professional writers don’t have the luxury of not having anything to write about. If they don’t write, they don’t get paid. And then they go hungry, and there’s nothing worse than a hungry, broke writer.

So do professional comedy writers have a magical fountain to draw comedy topics from? Unfortunately, no. They just have the talent for finding humor in everyday events.

Luckily that skill can be developed and trained. Humor is all around us in the everyday things we do. All you need to do is to tune in to it, mine it, and use it.

For three days we want you to make a list of all the humorous things that go on around you. If something happens that makes you chuckle or laugh, put it on the list. If you hear a witty comment, write it down. If you see something that amuses you, mark it down. Shoot, it can even be something you see or hear on TV. The only requirement is that it somehow strikes you as funny or as something you can make funny.

Those incidents can also be things that annoy, intrigue, or mystify you. There’s humor in those situations, too.

It’s important to note that at this point, you’re not writing jokes, you’re just gathering ideas.

On the fourth day, review your list. You now have a collection of topics that are ready to be used at any time. Pick one item on your list and write ten jokes using it as your topic.

Your list may look something like this:

•A car cuts me off on the highway and then slows down.

•Telemarketers always call when we sit down to dinner.

•At the store, not one salesperson offered to help me.

•I received an e-mail from an old high school friend volunteering me for some committee.

As you can see none of these are jokes. They really aren’t even that funny. But each one can be used to generate jokes. That’s what we want you to do—start picking up on the things that go on around you that you can use in your comedy writing.

In this exercise you’re doing this consciously, but pretty soon you’ll be finding humor without even realizing it.

Exercise 10

Inspired by Legends

We used to play tennis with a group of extraordinarily mediocre players. We approached competence only about once a year—while the Wimbledon matches were being televised. Most of our colleagues watched the tournament and consequently played a little better than they normally did. There were probably two main reasons for this. First, watching the play was instructional. We all saw the strokes of the quality players, and we picked up some of the strategy of world-class tennis competition. Second, it was inspirational. We watched great players playing great matches. We thought if Martina Navratilova could perform that brilliantly, so could we. We were eager to emulate Pete Sampras and Roger Federer. We played just a tad better.

Great jokes also can be instructional. If a certain joke gets the desired results, it must have been brilliantly conceived and perfectly executed. Studying the gag and the efforts that went into producing it is a great teaching tool in learning to write solid comedy.

But good jokes also can inspire us. They can awaken in us a desire to write material as good as or better than the ones we hear or read. Even if we don’t live up to that lofty desire, we still manage to learn to write a tad better. What’s wrong with that?

We’d like to begin this exercise by having you select a few specific topics. Let’s say about six of them. They can be about anything at all. You may even glance through a collection of jokes and select topics at random. Traffic, dating, growing older, marriage—whatever topics you want.

Once you’ve made your choices, begin to research some superb jokes on those topics. You may select some that you have in your list of great jokes from Exercise 1 or you may gather some new ones.