Читать книгу Chrysler's Motown Missile: Mopar's Secret Engineering Program at the Dawn of Pro Stock - Geoff Stunkard - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Science Class

ОглавлениеThough professional cars often made racing news headlines, it was the everyman’s stock-class drag racing divisions that remained more important to the factory for promoting new car sales, and the Race Engineering group stayed busy with projects and research related to that during the 1960s. Indeed, many in the team’s cadre of engineers formally dropped out of actual competition in late 1967, retiring their ever-evolving Funny Car and turning the Top Fuel car over to a mostly outside crew. After all, the exploding muscle car business had grown into a big part of vehicle marketing, which was further spurred on in 1967 when the NHRA divided its raced stock cars between a Junior Stock–style lower division simply named “Stock” and a new standalone Super Stock division to showcase the best factory cars and drivers.

Ever scientific in approach, Hoover knew testing was paramount to this division’s success. As a result, select factory-associated cars and drivers began showing up one day a week at Motor City Dragway near Mt. Clemons, Detroit Dragway at Sibley, Dix south of downtown, Milan Dragway west of the city, or even a faraway location such as a track in California when the racing season started. Rented by the company for private use to experiment with new ideas such as hood scoop shapes, special tires, or promising cam designs, these test sessions became part of the legend of Chrysler Engineering “doing so much with so little.” By 1969, Al Adam, yet another Ramcharger alumni, was managing that aspect of real-world testing with Spehar doing the engine prep; both men were meticulous at record-keeping. Edited notes on successful experiments were forwarded to Chrysler racers across the nation.

Some tests were done with cars recently prototyped in an offsite-from-Engineering location simply known as the Woodward Garage. Located in a former Pontiac dealership at the corner of Woodward and Buena Vista in Highland Park, this small private shop served as the skunkworks for ideas that Hoover or his compatriots dreamed up for racing under factory authorization or for special projects done on existing cars. UAW shop steward and top mechanic Larry Knowlton was the unofficial manager at the garage.

During late 1967 and early 1968, at Mr. Hoover’s request, Knowlton and a brilliant, somewhat flamboyant young engineer named Robert “Turk” Tarozzi reworked a Race Hemi into the small Plymouth Barracuda. Once they put it all together, the result was one of the most notorious drag racing combinations ever authorized by Detroit. That spring under contract for Chrysler, shifter-company-turned-vehicle-constructor Hurst Industries converted approximately 160 of these A-Body models (both Barracudas and Dodge Darts) into Hemi-powered drag-race-only machines in a Detroit-area facility. They came to conquer under the tutelage of factory-favored drivers, such as Ronnie Sox, Arlen Vanke, Don Grotheer, and Dick Landy. By then, Dave Koffel, a trained metallurgist who had been racing himself for many years, handled the deals with the racers.

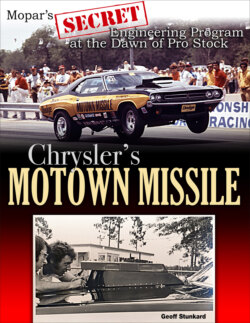

Development in the 1967–1968 era resulted in what many still consider the ultimate Chrysler race package: the Hurst Hemi package cars. This is the first Sox & Martin 1968 Barracuda, seen here at its initial drag test session at Cecil County Dragway in Maryland in April 1968. (Photo Courtesy Tom Hoover Archive)

Again, the rule makers were stymied. Reams of correspondence from Hoover, Koffel, Product Planning’s Dick Maxwell (yet another former Ramcharger), and others were sent out to NHRA officials in California, asking pointed questions about the factored horsepower the NHRA had placed on Chrysler engines, why Ford was allowed to run a combination no one in Detroit had seen except in the hands of that company’s best-known drivers, or why the new Six Pack Road Runners and Super Bees had no owner lists because they were actually sold as “street cars.”

This signed letter to the NHRA was among many that went back and forth between the factories and the NHRA in those days. Tom Hoover was always looking for an advantage, although he later admitted that the NHRA never forgave Chrysler for some of the things it did, such as the 1969 Mini-Nationals. (Photo Courtesy QMP Research Files)

Though perhaps frustrating, Mr. Hoover was always all-in on this game, figuring out the rule book, finding scarce racing combinations that had an advantage, and pushing the envelope. At times, those creative solutions likely had NHRA president Wally Parks cursing quietly at the sheer genius of it. At the same time, one of his angry division directors called NHRA tech boss Bill “Farmer” Dismuke at the organization’s North Hollywood offices to complain about what “them Chryslers” had done to the record book the past weekend. Hoover would laugh for a moment, then go right back to work to “crush them like ants,” as he was prone to state in private company.

It all came to head at the 1969 NHRA Nationals held in Indianapolis over Labor Day weekend. The NHRA knew that the best drivers in Super Stock (a very popular class by that time with factory attention) were hitting the brakes well before the finish line to keep from showing their top performances. At that time, if your car went too fast, you lost. Basically, any performance made during eliminations that exceeded the current NHRA elapsed time index broke out, going beyond its established performance. When that happened, the car was disqualified from advancing to the next round.

Super Stock: Racing on the Brakes

Each Super Stock car had a set elapsed time index. This was derived from the possible performance of that combination based on an NHRA-factored horsepower-to-weight ratio. Each engine was rated for horsepower as estimated by the NHRA’s Technical Committee, which in turn was coupled to the manufacturer’s stated overall weight for each car as released off the assembly line. Weighed without driver, the engine/car package would then fall into a select letter category. For example, “A class” was the highest horsepower/lightest car combination, followed by B, C, D, etc. Automatic and manual transmissions were further broken into their own subgroups in each class to provide additional equality; automatic-equipped models had an A after the class letter.

At big events, each group of identically classed cars raced each other for a class victory among peers, and winners then advanced to final eliminations. At smaller races, the driver would simply be timed against the index. Once racing among all those classes was underway, the slower-classed car was given a head start by whatever the calculated index difference was.

During the 1969 season, entries in the Super Stock classes ranged from SS/B (solely the Hurst Hemi cars because no one had built a car in a weight legal in SS/A at that time) through SS/J. A like number of cars were classified in the automatic transmission classes that were identified with an additional A at the end of the classification. So that year, the 10 class letters and 2 transmission choices meant 20 possible classes.

Originally stated as an NHRA-set minimum elapsed time, the index for each class in 1969 was based on the current class record for that class. No one wanted to beat that record if possible because it left no room for error. In other words, resetting a soft index record might make winning less possible by requiring the maximum effort on every single run. Furthermore, changing the record would affect every driver racing that combination, not just the cars capable of running to that level. As a result, and sometimes at factory direction, the fastest cars were often braking at over 100 mph to prevent this from happening.

Hemi race car drivers, such as Dick Oldfield in New York and Don Carlton in North Carolina, were familiar with this technique. It was dangerous, and the racers frankly hated it. Pro Stock would eventually solve this problem for many of them.

So, going into their biggest event of the year, the NHRA decided to catch the racers at their own game. This was when the NHRA stated that at Indy every run down the track could become the index for Monday’s finals. Since only the class winner and runner-up from Saturday afternoon’s class runoffs were allowed to advance to race in Monday’s final eliminations, these new racing indexes would obviously be derived from the fastest runs made during that weekend. This was because the NHRA assumed every driver would have to run flat out to win a class crown. Still, to make it fair, they also agreed that the index would not change again on Monday. For the first time, drivers could run flat out all day and the record rule would not apply until the final. In the final round, the drivers could run as fast as necessary, but that fast time was the new index heading into the following event.

On Friday morning, the Chrysler racers slowly left town, heading for a little track just over the Ohio state line a couple of hours east. Dave Koffel rented the track with his American Express card, and now each of the three-dozen-plus drivers arriving there would make three passes to see who was truly fastest. The two best in each class would then return to Indy to run for the class win and runner-up slots. Once Chrysler had determined who the fastest guys were fair and square (away from the oversight of NHRA officials), the three chosen duos in SS/B, SS/BA, and SS/CA (all Hemi cars exclusively) returned to Indianapolis and basically cruised downtrack on Saturday for the class battle and “new” records. The predetermined faster car from the so-called “Mini-Nationals” also deliberately ran slower to be the class runner-up, all of which kept the old indexes used before the Nationals completely intact. Meanwhile, the other guys fought each other hard, and most had killed or reset their indexes when clocking their best possible number round after round in taking class victories. For their part, Hoover, Maxwell, and factory race boss Bob Cahill wandered around the Indy pits on Friday morning, shrugging off questions about where all the absent racers had gone.

This was it, the starting line at Indianapolis Raceway Park, where victory and defeat were a literal split second away. It was this event that had the most attention from the racers, the press, and the factories. (Photo Courtesy Dick Landy Family)

The staging lanes at Indy in 1969 did not host a lot of Hemi SS entries after the runoffs were done at Tri-City Dragway in Hamilton, Ohio, early in the weekend. Ted Spehar still calls the so-called “Mopar Mini-Nationals” the greatest race in which he was ever involved, as there had never been a true no-holds-barred NHRA Super Stock runoff to the last man standing before that. (Photo Courtesy Dick Landy Family)

This photo in the Spehar family archive from November 1970 shows the Silver Bullet when it was first completed. This car would be as legendary on the street as the Motown Missile was on the track, which was something Mr. Hoover took pride in. (Photo Courtesy Spehar Family Archive)

When Monday’s big event arrived, the only thing the Mopar racers from those classes needed to do was make sure they did not redlight at the start. When the smoke cleared from five rounds, Ronnie Sox won, beating a 1964 Hemi Plymouth driven by Dave Wren to basically close out the professional Super Stock era. On that Tuesday morning, NHRA officials, the movers and shakers in Super Stock, and their factory bosses all got together and agreed to formulate new rules that would create a heads-up class for 1970, which they would call Pro Stock. Finalized after the NHRA World Finals in Dallas that October, this was a new challenge, one Mr. Hoover would relish even as factory street performance was increasingly choked by emissions, insurance costs, and other factors.

Imitating a popular sanctioning body design, this is a North Woodward Timing Association decal.

By 1969, Hoover’s terrible Coronet was now sitting at home more often than not, as Jimmy Addison and Ted Spehar kept the 1962 Dodge with its Max Wedge powerplant busy making money. They would soon begin converting a former factory-tested 1967 440-ci GTX into perhaps Woodward’s most notorious competitor, the Silver Bullet. That project would come together for the street as the Motown Missile would soon do for the dragstrip. “Crush them like ants,” Mr. Hoover said and smiled.

* * *

Ted Spehar was quietly contemplating what would come next in his future as he looked over the empty 1,500-square-foot building on Fernlee Avenue near where it intersected West 14 Mile Road in Royal Oak. Perhaps it was a big jump to go into this business of special car fabrication and maintenance, but he had the confidence, the connections, and the work ethic to be successful. He needed room for cars such as The Iron Butterfly and the factory test cars, for this new Pro Stock thing for spare parts, a clean room for engine construction, space for machine tools, and whatever else the new contract from Chrysler required. Most important for everyone involved, it was a secure, quiet place almost invisible to the outside world. After all, ideas that matter could be kept quiet until they were needed, which they certainly were. The commercial space realtor talked softly with Jack Watson, better known as the “Hurst Shifty Doctor” and the person who had arranged the meeting. Giving Ted some personal space to figure it all out, the realtor was expectant, hoping this day spent with the unassuming gentleman who was supposed to be some kind of engine genius would indeed become a successful sale.

* * *

Ted Spehar, who would play the most primary role as the Motown Missile’s builder and owner, traveled a special road to get to where he was that afternoon. From service station owner to engine builder, the past dozen years laid the groundwork for what would become Spehar’s most visible position in motorsports, though such efforts characterized his entire career. With Chrysler’s business getting more tied down with government and industry volatility, executive Cahill and Mr. Hoover had concluded that Ted was the right guy to help manage the firm’s drag race development work as an outside contractor. The unionized Woodward Garage would likely be shuttered regardless, so from here on out, the things Mr. Hoover wanted to change from dream to reality were done in a comprehensive manner under Spehar’s tutelage.

Ted Spehar stands next to a dragster he owned in the early 1960s, driven by racing buddy Deowen “De” Nichols. This was the third chassis ever built by the Logghe Brothers and used a flathead Ford for power. (Photo Courtesy Spehar Family Archive)

A snapshot from December 1963 shows the Texaco station where Ted did his early work. The dragster is parked outside on a cold but snowless Michigan day. (Photo Courtesy Spehar Family Archive)

Ted was a Detroit-area native (having grown up in Birmingham) and a hot rodder from the late 1950s, following in the footsteps of his older brother Peter. He and street racing partner Deowen “De” Nichols got serious and bought the third dragster chassis ever built by the legendary Logghe Brothers firm, but Ted’s true penchant was engine building. It was through his prowess in this arena that he made initial introductions to Chrysler’s corporate office and the Ramchargers team during the mid-1960s, which was thanks in part to a working relationship with Dick Branstner, who was a larger-than-life figure in Detroit’s car-building scene at the time. Ted’s wife, Tina, a young beautician, ironically did hair styling with some of the other wives of Detroit’s performance set, which is how the Branstners and Spehars met.

While Tom Hoover handled the Ramchargers racing engine builds personally, Ted was often given the recommendation when others came asking for services. His real interaction started in 1965, when he was still working out of the Texaco station located at 15 Mile Road and Adams Street that he purchased when he was 22 years old. He called the engine business Spehar’s Performance Automotive and began working almost exclusively on Chrysler products.

In 1967, he sold the Texaco franchise and bought a Gulf station located at 14 Mile Road (one block from Woodward) and continued to grow his corporate portfolio by working with Dale Reeker and Dick Maxwell from Chrysler’s Product Planning arm on media test car prep and building engines for specific Chrysler racers. The following year, Ted purchased the legendary Sunoco franchise right on 1775 Woodward that he subsequently turned over to his top mechanic, Jimmy Addison, for doing regular car work. Note that the sale of petroleum was not always a big money generator at these outlets because Ted was often so focused on whatever horsepower task was at hand that actual fuel customers would drive off in disgust, waiting for a pump jockey who never arrived. Ted noted wryly that this was a likely factor in the Gulf franchise eventually changing hands.

Meanwhile, that Gulf station served his more immediate purpose of being the place Product Planning sent new cars to be super tuned for the automotive media. Ted would blueprint the distributor and cam, dial in the carburation as needed, and (when called on) would perhaps add a little more to the as-released vehicle. This was very rare, and the most visible occurrence happened when he was told to put a just-released 1969 M-code 440 Six Pack Road Runner together for Ronnie Sox to drive for Super Stock & Drag Illustrated magazine. Sox made several quarter-mile runs in the 12-second range, which was faster than the large car could have been expected to accomplish, even with Hemi power!

When Dick Housey drove a 1965 Plymouth for which Ted had built an engine, they went to the runner-up spot at 1965 NHRA Winternationals and reset several records, running in Modified Production on occasion. (Photo Courtesy Spehar Family Archive)

The Iron Butterfly, built in two weeks from a 6-cylinder car that Ted Spehar’s wife Tina had been driving, was created to fit into SS/CA by using an aluminum front end and a circa-1964 Hemi race engine. Seen here under the tutelage of driver Dick Oldfield, on this day the car posted runner-up honors to Ronnie Sox at the 1969 NHRA World Finals. (Photo Courtesy quartermilestones.com, Ray Mann Archive)

This is an early decal from Ted’s business, which for several years was based out of the service stations he owned. (Photo Courtesy Spehar Family Archive)

The now-recognized Detroit engine builder had a very busy year in 1969. In addition to the factory magazine demonstrators and at the behest of Mr. Hoover and company, that late summer found Ted converting his wife Tina’s street-driven Slant Six 1964 Dodge Polara into an SS/CA-class Hemi car he called The Iron Butterfly. Accomplished in a few weeks leading up to the Indy Nationals by working mainly outside behind the Woodward Sunoco station because garage space in all of the buildings was at a premium, the fresh vehicle was driven first by noted Detroit racer Wally Booth at the Nationals. Then, it was turned over to a new mechanic with a college engineering background from New York named Dick Oldfield.

Oldfield’s deployment as the driver came about from Dave Koffel’s recommendation and the shop contract Spehar recently signed with Chrysler. Oldfield was a dominant figure in NHRA Division 1 racing, and he already had the driver points from racing his Good Guys Dodge Dart that were needed to be able to compete with the Butterfly at the NHRA World Finals. This he did well, going to the event’s final round before falling to Ronnie Sox, who won his first NHRA World Championship in the other lane.

Moreover, that Chrysler contract was the reason for the new location Ted found on Fernlee with friend and Hurst employee Jack “Doc” Watson. The Gulf station was being sold, and Jimmy Addison bought the Sunoco station from Ted at the same time. As winter approached, the 1960s came to an end and Ted and his new group of employees got to work. None of them ever looked back as the revolution of Pro Stock dawned on the horizon for 1970.

* * *

Ahead stretched a measured eighth-mile of pavement as Don Carlton squinted through his black-rimmed glasses at the Christmas tree. He was oblivious to the girls on the fence, their guys leaning forward for a better view. The top bulb turned on, and the staging bulb below it flickered on in the evening haze and remaining tire smoke as he carefully rolled the Hurst-built Hemi Barracuda that he named Lil’ Thumper into the starting beams. His opponent, in a Ford Mustang, did likewise. Now came the countdown of five lights.

Yellow … Yellow … Yellow … Yellow …

Don knew that if he saw the green light come on, he was too late. With the pedal to the metal and the Hemi engine screaming for mercy, he sidestepped the clutch and the Plymouth leapt forward with its front wheels hanging a half-foot off the pavement, aided in part by gold-dust rosin sprinkled on the starting line. The next throw was down into second, and the Mustang could no longer be heard as the Hemi engine’s RPM climbed the second time against the steep 5.13 rear gear. With a quick read of the tachometer and the ball-knob shifter in his hand, he flashed across the shift pattern up into third, and the finish line loomed immediately ahead. Fourth gear in the eighth-mile was almost anticlimactic, but he took it down through the final gate anyway with the Mustang behind by a car length. Round one down; two more to go.

* * *

“Run whatcha brung” Southern-style match racing in the Carolinas was a way of life for many amateur racers by this time in 1969. They ran against each other on grass-aproned strips of asphalt barely wide enough for two race cars to fit side by side. Indeed, some of the cow pasture emporiums ended in shut-down areas that required the drivers to quickly lift up from the gas and brake hard because the track actually narrowed to a single lane.

Lenoir, North Carolina, is a quiet town located north of US Route 70 and Interstate 40 in the hill country known as the Piedmont region of the Tar Heel state, and Don Carlton was one of several talented drivers from the area. NASCAR star Bobby Isaac was from nearby Hickory, while the Petty clan was over in Randleman, and Junior Johnson led his crew of circle-track merry men from up North Wilkesboro way. Drag racers included Ronnie Sox in Burlington, young upstart Roy Hill from Randleman, and Stuart McDade, who was also right from Lenoir.

To be honest, Southern-style racing of all forms was its own breed. The NASCAR guys had been the forerunners in competition, earning their stripes at the track in Darlington since 1950 and occasionally in prison garb when caught running or making high-grade moonshine. Drag racing was a simple contest of getting to the end first, and if you didn’t buy enough right from the factory, you innovated to make sure you had more: a little weight removal, sticky retreaded tires, California-type speed parts, or nitromethane blended into gasoline on some occasions for a concoction known locally as cherry mash. Promotors (such as Bobby Starr at Piedmont near Burlington) paid cash to the winners, and the rules were sometimes as simple as “four wheels, 3,000 pounds, and doors.”

Don Carlton posed for these publicity photos when a sponsor package came to the Motown Missile team. (Photo Courtesy Spehar Family Archive)

Don was not the son of some scion of Southern gentility. He funded his racing through long hours of work at one of a myriad of furniture factories that then dotted the countryside of the Piedmont. After a stint in a 4-speed Chevrolet, he bought an RO-code 1967 Plymouth Belvedere that was somewhat similar to the 1966 car Mr. Hoover owned but with some race-lightened parts right from the factory. He then waited in line to buy one of the Hurst-built Barracudas in 1968.

He raced it locally, but the car was badly damaged late that year in a towing accident. He called Buddy Martin over in Burlington, who not only agreed to buy the carcass but offered Don the job of driving one of the team’s many cars: first, a Modified Production Road Runner; then, Lil’ Thumper, a 1968 Barracuda set up as a match racer. This car was created to run Southern-style events and in the AHRA’s new heads-up Super/Stock Experimental class, where Ronnie Sox himself sometimes took over the driving. Still, Buddy could book the car Don drove when he and Mr. Sox were out on tour with the monstrous Chrysler clinic responsibilities that Sox & Martin operation then performed. Carlton had already established himself as a fearsome driver when that 4-speed was in his hand.

In 1969, Don spent considerable time driving for the Sox & Martin team in this match-race Barracuda set up to run in heads-up AHRA races. It is seen here at the 1969 Super Stock Nationals in York, Pennsylvania, running a special SS/X division at that solitary race. However, Ronnie Sox himself drove it on that weekend. (Photo Courtesy quartermilestones.com, Pit Slides Archive)

Into the air and onto history’s pages, the Motown Missile takes flight during a test session. (Photo Courtesy Spehar Family Archive)

At this point, Don was likely unaware that he would soon become one of the most notorious drivers in the formative years of Pro Stock, a class that was similar in theory to what the AHRA was already running as S/SE or Super Stock Experimental. Humble and well-versed in what a hard day’s work entailed, he and the Sox & Martin operation soon parted ways. After a stint with colorful car owner Billy Stepp, Don had a chat with Mr. Hoover and agreed to take over driving the Motown Missile test mule from Dick Oldfield in early 1971.

His black-rimmed glasses actually made him the perfect complement to what Chrysler by then was calling the Special Vehicle Engineering group. They had computers and a weather station, brilliant ideas, and a tireless calling via testing to make it all work. On the 4-speed, Don Carlton was considered the equivalent of a cyborg, half man and half machine, repeating test after test after test. It would yield impressive results until a fateful 1977 day when he proved to be all too human.

* * *

The Motown Missile legend emerged from this soup of people and backgrounds. The world of drag racing was about to see what was possible when you pushed the envelope of technology. The silo was now ready for a weapon.