Читать книгу Chrysler's Motown Missile: Mopar's Secret Engineering Program at the Dawn of Pro Stock - Geoff Stunkard - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

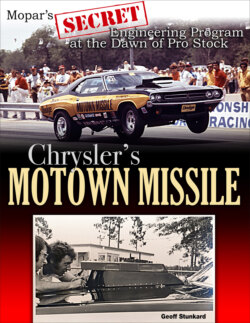

ОглавлениеNoted artist David Snyder created this symbolic view of the legendary Woodward Sunoco garage during the era of the Silver Bullet Plymouth, seen parked outside. The passion for performance is what spearheaded the work that led to the Motown Missile on a more national scale. Jimmy Addison owned the service center at this time. (Photo Courtesy www.davidsnydercarart.com)

Chapter OnePreflight Check in Autumn 1969:Origins of the Motown Missile

Dusk began to fall as Jimmy Addison worked to get the nondescript Dodge ready for the night, his work-worn hands up underneath it inside the lit garage bay. Outside the Sunoco station, automobiles in bright shades of paint cruised by, some drivers looking over briefly at the car hoisted up on the lift, others more intent on getting to Ted’s drive-in restaurant, to the next stoplight, or beside the next wise guy. There was a rumble outside and the ring of the service station bell as a rich green Corvette roadster with factory side-pipes rolled up to the pumps. Any 435-hp L71 Tri-Power out on Woodward wanted what was needed, and what was needed was gallons of Sunoco 260. After a quick glance from Jimmy, one of the young guys in the garage bay wiped off his hands and walked out to see a young executive (maybe right from GM) and his lady friend sitting inside the brand-new car. He saw the $20 bill hanging out the window, heard him say “Fill ’er up!,” and started the pump. Jimmy went back to work underneath the rough-looking 1962, getting the Max Wedge Mopar ready to win some Saturday chump change.

* * *

Addison became one of the legends of Woodward Avenue in its heyday. Muscle cars and marketing were the going thing in the bedroom-community suburbs of Detroit, and this long stretch of four-lane pavement running northwest from the center of the city to the town of Pontiac was considered by many to be ground zero for the cause. Indeed, so much so that Pontiac, the car brand, originator of the GTO, had run a national advertisement showing a new version of its tiger with a Woodward Avenue street sign prominently displayed that was clearly intended to show everyone which way was up.

For the cruisers and the crazies, up was someplace close to 19 Mile Road (near where the popular local eatery Ted’s drive-in was located), and then it began a circuit southeast toward Ferndale or to 9 Mile Road. Each of these east-west numbered “Mile” streets was named for the number of miles from the center of the city of Detroit. On a busy night, most participants would turn around and make the circuit a few times, perhaps stopping at Addison’s Woodward Sunoco fuel depot for a tank of hi-test fuel if the ride required it. The respectable ones all did.

Addison was a short, stocky guy noted for a somewhat gruff demeanor and a fearless driving style. A former line mechanic for an Oldsmobile dealership, he had been at the Sunoco station at 14 Mile since 1968 and would soon own it himself.

Thanks to Ted Spehar’s meticulous engine building skills and the car’s unkempt outward appearance, the stroked Max Wedge 1962 Dodge was something of an unknown terror on the street—which was good for business if your business was street racing and dudes such as that guy in the ’Vette were looking to impress a member of the other sex. They had money. You wanted to take it. Let the best man win.

At any rate, while the Woodward Dream Cruise has now become a part of yearly American automotive culture, in 1969 it was simply a thrill for the participants, a pain for the police, and a legend across the nation. This was a place where you might see something new from the factory before everyone else, show off the latest mods to your street machine, meet friends and friendly foes, and maybe find out who the king of the hill was for the night. If a stoplight-to-stoplight joust wasn’t enough, you could chase more serious competitors to top-end honors into the triple digits (MPH) on the under-construction I-696 (basically the former location of 10 Mile Road) or on a temporarily measured quarter-mile on a more deserted side street after midnight. When that happened, there was a deal, there was money, and there was the danger of arrest or worse. It was a unique moment, perhaps a semi-requiem from the madness of Vietnam, politics, labor unrest, and the like. “Papa’s got a brand-new bag, and it was street racing,” as one magazine scribe explained it. The machine spoke, and it had a reputation to uphold. Perhaps this passion is where the Motown Missile truly had its roots.

* * *

Mr. Hoover looked over his glasses at the needle on the dyno as the roar increased and the RPM level climbed again. Built into the basement of the company research building in Highland Park, the dynamometer cells were normally tasked with more pedestrian projects these days, but Tom could get special dyno use for his projects when needed, especially since he had friends who were the actual operators. Today, it was another potential idea—this time just a simple change to a new race camshaft that might show some improvement to airflow and a little more horsepower. It wasn’t much, but it had already proven to be worthwhile in real-world conditions over at Detroit Dragway the previous week in a test car.

With the right carb adjusting complete, the needle showed there had been about a 7-hp improvement over the previous-best version of that cam. The numbers were denoted by a slightly higher bump on the top of the hand-drawn arch when plotted on a subsequent graph. Now proven to be truly beneficial, a notice was forwarded to the chosen Chrysler racers across the nation, announcing the exact part number to order from the manufacturer. Tom Hoover smiled to himself.

* * *

In the teardown barn at Pomona in 1963, engineer Tom Hoover casts a warning glance over his shoulder. The Ramchargers played a vital role in how Chrysler Race Engineering was accomplished in the early days of development. (Photo Courtesy Tom Hoover Archive)

Even as the Race Engineering guys became involved in engine development, the Ramchargers team was winning races. Shown after a victory at the 1963 NHRA Nationals are Herman Mozer and Jim Thornton (standing, left to right); Gary Congdon, Tom Hoover, and Dale Reeker (front row); Dan Mancini and Tom Coddington (middle row); and Mike Buckel and Dick Maxwell (back row). All were smart guys, hard workers, and passionate racers. (Photo Courtesy Spehar Family Archive)

Engine science. For Thomas Meridith Hoover, this subject was his life’s focus for more than a decade, working diligently in the depths of Chrysler Engineering’s buildings in the Motor City. He had been a hot-rodder since high school, and after training as a graduate physicist at Penn State, he landed at the company in 1955, just as performance began to get more serious. Following training at the Chrysler Institute, he worked on various projects as an engine developer until new company President Lynn Townsend called on him in late 1961 to head a new Race Engineering project with the explicit goal to put a Chrysler vehicle into the winner’s circle at “Big Bill” France’s huge superspeedway in Daytona Beach. The Daytona 500 was now important enough to sink real money into. After all, the motto was “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday,” right?

With that as the plan, Tom lost no time surrounding himself with similar-minded gentlemen who he knew within the firm. In fact, he was even somewhat recognized outside of the corporate world, as he and other young members of the Chrysler Engineering team had formed a drag race club in the late 1950s, calling themselves the Ramchargers. This was named after a closely guarded secret about fuel-related intake tuning that the company’s engineers had discovered, scientifically verified, and put into practice while testing the original 1950s-era Chrysler Hemi engine for an Indy Car program.

During the NHRA Nationals drag races held at Detroit Dragway in 1959 and 1960, the ’Chargers had frustrated the tech inspectors with a prewar Plymouth featuring many hair-raising ideas. Mission accomplished. Tom and his band of slide-rule renegades had next jumped into what was known as Stock Eliminator for 1961, where they could measure their technology and prowess against other factory-designed equipment. While NASCAR success may have been a more visible focus on the corporate front, Tom’s own passion was fueled by the quarter-mile bursts (events in which anyone could participate), and the company was soon developing special cars just for this. The first of them used a 413-ci engine using the ram-tuning intake technology, the same 1962 engine package that Jimmy Addison was later street racing. Formally called the Maximum Performance package, it was better known simply as the Max Wedge.

Meanwhile, with the Ramchargers team busy winning races on the weekends, Tom Hoover was hard at work during 1963 getting a reconfigured Hemi cylinder head prepared for future Daytona and drag racing use alike. Working with specialists, including legendary airflow engineer Sir Harry Weslake of England, Hoover determined a way to mount a revised version of the head onto the latest wedge-head 426-ci RB-series engine block. Everyone involved then went to work on a very tight schedule to get the new powerplant to live for a full 500 hard miles—with the dyno cells in Highland Park screaming for hours on end during the winter months of early 1964. The effort was highlighted by near-unreal background drama and a movie-type happy ending—with young star Richard Petty thundering his Hemi Plymouth Belvedere to victory in the final act at the 1964 Daytona 500, leading several other new 426 Hemi Chryslers across the finish line. The world was never the same after that February afternoon. At least not in the automotive world, and certainly not in places such as Woodward Avenue.

Compared to most other engines, the Hemi engine was huge in its overall dimensions, nicknamed by some as as “the elephant motor.” It had big ports and large valves positioned opposite each other at a 53.5-degree axial difference inside a hemispherical (or half dome) combustion chamber. This was a perfection discovered by long-since-retired Chrysler engineers during extensive testing on a wartime airplane engine in the 1940s. It had forged aluminum pistons that were the heaviest design created for a passenger car engine at the time, and a race-specific reciprocating design and hardware that was created for durability. Ultimately, the Hemi created an icon for Chrysler as a company and a lasting legacy for its “godfather,” Tom Hoover.

It also created a lot more headaches for the tech guys and rule makers in all sorts of racing because it could win—which it did, a lot. In fact, NASCAR actually banned the Hemi for 1965 as a non-production engine, allowing Mr. Hoover and company a little spare time to figure out how well it might run on nitromethane fuel in the supercharged Top Fuel dragster environment with a new Ramchargers team dragster. The Ramchargers also raced and won with it that season after installing a fuel-injected variation of the engine into a series of radical creations they had recently dreamed up as an “unlimited stock” idea in late 1964.

These so-called altered-wheelbase machines, featuring the front and rear wheels both pushed far forward beneath the body, quickly became known as Funny Cars. Meanwhile, the factory released a group of 200 1965 all-steel 426 Hemi race cars for the NHRA’s Super Stock class. One of those was a Plymouth Belvedere being successfully campaigned by local racers Dick Housey and Ted Spehar that year. Against this backdrop, work was ongoing throughout 1965 to address the NASCAR problem directly. This was done by creating a more pedestrian version (as if such terms ever applied to a Hemi) of the engine that could be sold in a street “stock production” model.

The ban of the Hemi by NASCAR for 1965 freed up resources to experiment in drag racing, which resulted in cars such as the altered-wheelbase Dodge the Ramchargers campaigned that year, which was both fuel-injected and running nitromethane when this photo was taken. (Photo Courtesy Tom Hoover Archive)

In fact, Mr. Hoover bought one of these cars as soon as they arrived for 1966—a green Dodge Coronet. He once recalled that the car had a brand-new Hemi installed that had been built incorrectly from day one at Chrysler Marine & Engineering, which was where all the code A102 street Hemi engines came together for the street models. Once sorted out, he did some drag tests with it and drove it for fun on the street, sometimes turning it over to Spehar, a man he trusted, for tune-up care and feeding.

Starting in 1965, several factory-associated cars were often under the care of Spehar, who owned a Texaco service center and later a Gulf gas station franchise in the area. On that note, on some occasions, Mr. Hoover made sure he was attending a company or social function in the evening, because Spehar’s mechanic Jimmy Addison was covertly taking the Hoover green meanie out near Woodward to uphold company honor against the other guys. He usually did, too.

Tom Hoover’s factory crew was not huge. His first guys in the Race group were Dante “Dan” Mancini and Jim “B.B.” Thornton, both trusted associates from the Ramchargers team. Indeed, other Race Engineering guys would include fuel systems specialist Tom Coddington, nicknamed “The Ghost,” Ramchargers driver and engine specialist Hartford “Mike” Buckel, and several others, all of whom understood the passion that drove the projects.

Members of the Ramchargers worked throughout other areas of the Chrysler Corporation, where they were called on to do special race-focused projects when their production-associated work was completed. Not commonly recalled is that the Ramchargers (and a sister factory-member team named the Golden Commandos that raced Plymouths) were nearly independent from the corporate offices. Other than what little money could be had from dealership sponsorship and professional access to the factory development tools, it was pretty much an out-of-pocket proposition for both groups, and neither team ever had big factory dollars to live lavishly. The teams relied on member dues and winning real races to stay viable financially. It was ingenuity and dedication that would often spell the difference in that regard.