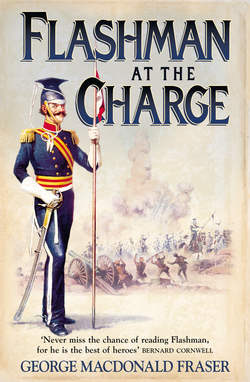

Читать книгу Flashman at the Charge - George Fraser MacDonald - Страница 10

ОглавлениеThe moment after Lew Nolan wheeled his horse away and disappeared over the edge of the escarpment with Raglan’s message tucked in his gauntlet, I knew I was for it. Raglan was still dithering away to himself, as usual, and I heard him cry: ‘No, Airey, stay a moment – send after him!’ and Airey beckoned me from where I was trying to hide myself nonchalantly behind the other gallopers of the staff. I had had my bellyful that day, my luck had been stretched as long as a Jew’s memory, and I knew for certain that another trip across the Balaclava plain would be disaster for old Flashy. I was right, too.

And I remember thinking, as I waited trembling for the order that would launch me after Lew towards the Light Brigade, where they sat at rest on the turf eight hundred feet below – this, I reflected bitterly, is what comes of hanging about pool halls and toad-eating Prince Albert. Both of which, you’ll agree, are perfectly natural things for a fellow to do, if he likes playing billiards and has a knack of grovelling gracefully to royalty. But when you see what came of these apparently harmless diversions, you’ll allow that there’s just no security anywhere, however hard one tries. I should know, with my twenty-odd campaigns and wounds to match – not one of ’em did I go looking for, and the Crimea least of all. Yet there I was again, the reluctant Flashy, sabre on hip, bowels rumbling and whiskers bristling with pure terror, on the brink of the greatest cavalry carnage in the history of war. It’s enough to make you weep.

You will wonder, if you’ve read my earlier memoirs (which I suppose are as fine a record of knavery, cowardice and fleeing for cover as you’ll find outside the covers of Hansard), what fearful run of ill fortune got me to Balaclava at all. So I had better get things in their proper order, like a good memorialist, and before describing the events of that lunatic engagement, tell you of the confoundedly unlucky chain of trivial events that took me there. It should convince you of the necessity of staying out of pool-rooms and shunning the society of royalty.

It was early in ’54, and I had been at home some time, sniffing about, taking things very easy, and considering how I might lie low and enjoy a quiet life in England while my military colleagues braved shot and shell in Russia on behalf of the innocent defenceless Turk – not that there’s any such thing, in my experience, which is limited to my encounter with a big fat Constantinople houri who tried to stab me in bed for my money-belt, and then had the effrontery to call the police when I thrashed her. I’ve never had a high opinion of Turks, and when I saw the war-clouds gathering on my return to England that year, the last thing I was prepared to do was offer my services against the Russian tyrant.

One of the difficulties of being a popular hero, though, is that it’s difficult to wriggle out of sight when the bugle blows. I hadn’t taken the field on England’s behalf for about eight years, but neither had anyone else, much, and when the press starts to beat the drum and the public are clamouring for the foreigners’ blood to be spilled – by someone other than themselves – they have a habit of looking round for their old champions. The laurels I had won so undeservedly in the Afghan business were still bright enough to catch attention, I decided, and it would be damned embarrassing if people in Town started saying: ‘Hollo, here’s old Flash, just the chap to set upon Tsar Nicholas. Going back to the Cherrypickers, Flashy, are you? By Jove, pity the poor Rooskis when the Hero of Gandamack sets about ’em, eh, what?’ As one of the former bright particular stars of the cavalry, who had covered himself with glory from Kabul to the Khyber, and been about the only man to charge in the right direction at Chillianwallah (a mistake, mind you), I wouldn’t be able to say, ‘No, thank’ee, I think I’ll sit out this time.’ Not and keep any credit, anyway. And credit’s the thing, if you’re as big a coward as I am, and want to enjoy life with an easy mind.

So I looked about for a way out, and found a deuced clever one – I rejoined the Army. That is to say, I went round to the Horse Guards, where my Uncle Bindley was still holding on in pursuit of his pension, and took up my colours again, which isn’t difficult when you know the right people. But the smart thing was, I didn’t ask for a cavalry posting, or a staff mount, or anything risky of that nature; instead I applied for the Board of Ordnance, for which I knew I was better qualified than most of its members, inasmuch as I knew which end of a gun the ball came out of. Let me once be installed there, in a comfortable office off Horse Guards, which I might well visit as often as once a fortnight, and Mars could go whistle for me.

And if anyone said, ‘What, Flash, you old blood-drinker, ain’t you off to Turkey to carve up the Cossacks?’, I’d look solemn and talk about the importance of administration and supply, and the need for having at home headquarters some experienced field men – the cleverer ones, of course – who would see what was required for the front. With my record for gallantry (totally false though it was) no one could doubt my sincerity.

Bindley naturally asked me what the deuce I knew about fire-arms, being a cavalryman, and I pointed out that that mattered a good deal less than the fact that I was related, on my mother’s side, to Lord Paget, of the God’s Anointed Pagets, who happened to be a member of the small arms select committee. He’d be ready enough, I thought, to give a billet as personal secretary, confidential civilian aide, and general tale-bearer, to a well-seasoned campaigner who was also a kinsman.

‘Well-seasoned Haymarket Hussar,’ sniffs Bindley, who was from the common or Flashman side of our family, and hated being reminded of my highly placed relatives. ‘I fancy rather more than that will be required.’

‘India and Afghanistan ain’t in the Haymarket, uncle,’ says I, looking humble-offended, ‘and if it comes to fire-arms, well, I’ve handled enough of ’em, Brown Bess, Dreyse needles, Colts, Lancasters, Brunswicks, and so forth’ – I’d handled them with considerable reluctance, but he didn’t know that.

‘H’m,’ says he, pretty sour. ‘This is a curiously humble ambition for one who was once the pride of the plungers. However, since you can hardly be less useful to the ordnance board than you would be if you returned to the wastrel existence you led in the 11th – before they removed you – I shall speak to his lordship.’

I could see he was puzzled, and he sniffed some more about the mighty being fallen, but he didn’t begin to guess at my real motive. For one thing, the war was still some time off, and the official talk was that it would probably be avoided, but I was taking no risks of being caught unprepared. When there’s been a bad harvest, and workers are striking, and young chaps have developed a craze for growing moustaches and whiskers, just watch out.1 The country was full of discontent and mischief, largely because England hadn’t had a real war for forty years, and only a few of us knew what fighting was like. The rest were full of rage and stupidity, and all because some Papists and Turkish niggers had quarrelled about the nailing of a star to a door in Palestine. Mind you, nothing surprises me.

When I got home and announced my intention of joining the Board of Ordnance, my darling wife Elspeth was mortified beyond belief.

‘Why, oh why, Harry, could you not have sought an appointment in the Hussars, or some other fashionable regiment? You looked so beautiful and dashing in those wonderful pink pantaloons! Sometimes I think they were what won my heart in the first place, the day you came to father’s house. I suppose that in the Ordnance they wear some horrid drab overalls, and how can you take me riding in the Row dressed like … like a common commissary person, or something?’

‘Shan’t wear uniform,’ says I. ‘Just civilian toggings, my dear. And you’ll own my tailor’s a good one, since you chose him yourself.’

‘That will be quite as bad,’ says she, ‘with all the other husbands in their fine uniforms – and you looked so well and dashing. Could you not be a Hussar again, my love – just for me?’

When Elspeth pouted those red lips, and heaved her remarkable bosom in a sigh, my thoughts always galloped bedwards, and she knew it. But I couldn’t be weakened that way, as I explained.

‘Can’t be done. Cardigan won’t have me back in the 11th, you may be sure; why, he kicked me out in ’40.’

‘Because I was a … a tradesman’s daughter, he said. I know.’ For a moment I thought she would weep. ‘Well, I am not so now. Father …’

‘… bought a peerage just in time before he died, so you are a baron’s daughter. Yes, my love, but that won’t serve for Jim the Bear. I doubt if he fancies bought nobility much above no rank at all.’

‘Oh, how horridly you put it. Anyway, I am sure that is not so, because he danced twice with me last season, while you were away, at Lady Brown’s assembly – yes, and at the cavalry ball. I distinctly remember, because I wore my gold ruffled dress and my hair à l’impératrice, and he said I looked like an Empress indeed. Was that not gallant? And he bows to me in the Park, and we have spoken several times. He seems a very kind old gentleman, and not at all gruff, as they say.’

‘Is he now?’ says I. I didn’t care for the sound of this; I knew Cardigan for as lecherous an old goat as ever tore off breeches. ‘Well, kind or not as he may seem, he’s one to beware of, for your reputation’s sake, and mine. Anyway, he won’t have me back – and I don’t fancy him much either, so that settles it.’

She made a mouth at this. ‘Then I think you are both very stubborn and foolish. Oh, Harry, I am quite miserable about it; and poor little Havvy too, would be so proud to have his father in one of the fine regiments, with a grand uniform. He will be so downcast.’

Poor little Havvy, by the way, was our son and heir, a boisterous malcontent five-year-old who made the house hideous with his noise and was forever hitting his shuttlecocks about the place. I wasn’t by any means sure that I was his father, for as I have explained before, my Elspeth hid a monstrously passionate nature under her beautifully innocent roses-and-cream exterior, and I suspected that she had been bounced about by half London during the fourteen years of our marriage. I’d been away a good deal, of course. But I’d never caught her out – mind you, that meant nothing, for she’d never caught me, and I had had more than would make a hand-rail round Hyde Park. But whatever we both suspected we kept to ourselves, and dealt very well. I loved her, you see, in a way which was not entirely carnal, and I think, I believe, I hope, that she worshipped me, although I’ve never made up my mind about that.

But I had my doubts about the paternity of little Havvy – so called because his names were Harry Albert Victor, and he couldn’t say ‘Harry’ properly, generally because his mouth was full. My chum Speedicut, I remember, who is a coarse brute, claimed to see a conclusive resemblance to me: when Havvy was a few weeks old, and Speed came to the nursery to see him getting his rations, he said the way the infant went after the nurse’s tits proved beyond doubt whose son he was.

‘Little Havvy,’ I told Elspeth, ‘is much too young to care a feather what uniform his father wears. But my present work is important, my love, and you would not have me shirk my duty. Perhaps, later, I may transfer’ – I would, too, as soon as it looked safe – ‘and you will be able to lead your cavalryman to drums and balls and in the Row to your heart’s content.’

It cheered her up, like a sweet to a child; she was an astonishingly shallow creature in that way. More like a lovely flaxen-haired doll come to life than a woman with a human brain, I often thought. Still, that has its conveniences, too.

In any event, Bindley spoke for me to Lord Paget, who took me in tow, and so I joined the Board of Ordnance. And it was the greatest bore, for his lordship proved to be one of those meddling fools who insist on taking an interest in the work of committees to which they are appointed – as if a lord is ever expected to do anything but lend the light of his countenance and his title. He actually put me to work, and not being an engineer, or knowing more of stresses and moments than sufficed to get me in and out of bed, I was assigned to musketry testing at the Woolwich laboratory, which meant standing on firing-points while the marksmen of the Royal Small Arms Factory blazed away at the ‘eunuchs’.2 The fellows there were a very common lot, engineers and the like, full of nonsense about the virtues of the Minié as compared with the Long Enfield .577, and the Pritchard bullet, and the Aston backsight – there was tremendous work going on just then, of course, to find a new rifle for the army, and Molesworth’s committee was being set up to make the choice. It was all one to me if they decided on arquebuses; after a month spent listening to them prosing about jamming ramrods, and getting oil on my trousers, I found myself sharing the view of old General Scarlett, who once told me:

‘Splendid chaps the ordnance, but dammem, a powder monkey’s a powder monkey, ain’t he? Let ’em fill the cartridges and bore the guns, but don’t expect me to know a .577 from a mortar! What concern is that of a gentleman – or a soldier, either? Hey? Hey?’

Indeed, I began to wonder how long I could stand it, and settled for spending as little time as I could on my duties, and devoting myself to the social life. Elspeth at thirty seemed to be developing an even greater appetite, if that were possible, for parties and dances and the opera and assemblies, and when I wasn’t squiring her I was busy about the clubs and the Haymarket, getting back into my favourite swing of devilled bones, mulled port and low company, riding round Albert Gate by day and St John’s Wood by night, racing, playing pool, carousing with Speed and the lads, and keeping the Cyprians busy. London is always lively, but there was a wild mood about in those days, and growing wilder as the weeks passed. It was all: when will the war break out? For soon it was seen that it must come, the press and the street-corner orators were baying for Russian blood, the government talked interminably and did nothing, the Russian ambassador was sent packing, the Guards marched away to embark for the Mediterranean at an unconscionably early hour of the morning – Elspeth, full of bogus loyalty and snob curiosity, infuriated me by creeping out of bed at four to go and watch this charade, and came back at eight twittering about how splendid the Queen had looked in a dress of dark green merino as she cried farewell to her gallant fellows – and a few days later Palmerston and Graham got roaring tight at the Reform Club and made furious speeches in which they announced that they were going to set about the villain Nicholas and drum him through Siberia.3

I listened to a mob in Piccadilly singing about how British arms would ‘tame the frantic autocrat and smite the Russian slave’, and consoled myself with the thought that I would be snug and safe down at Woolwich, doing less than my share to see that they got the right guns to do it with. And so I might, if I hadn’t loafed out one evening to play pool with Speed in the Haymarket.

As I recall, I only went because Elspeth’s entertainment for the evening was to consist of going to the theatre with a gaggle of her female friends to see some play by a Frenchman – it was patriotic to go to anything French just then, and besides the play was said to be risqué, so my charmer was bound to see it in order to be virtuously shocked.4 I doubted whether it would ruffle my tender sensibilities, though – not enough to be interesting, anyway – so I went along with Speed.

We played a few games of sausage in the Piccadilly Rooms, and it was a dead bore, and then a chap named Cutts, a Dragoon whom I knew slightly, came by and offered us a match at billiards for a quid a hundred. I’d played with him before, and beat him, so we agreed, and set to.

I’m no pool-shark, but not a bad player, either, and unless there’s a goodish sum riding, I don’t much care whether I win or lose as a rule. But there are some smart alecs at the table that I can’t abide to be beat by, and Cutts was one of them. You know the sort – they roll their cues on the tables, and tell the bystanders that they play their best game off list cushions instead of rubber, and say ‘Mmph?’ if you miss a shot they couldn’t have got themselves in a hundred years. What made it worse, my eye was out, and Cutts’ luck was dead in – he brought off middle-pocket jennies that Joe Bennet wouldn’t have looked at, missed easy hazards and had his ball roll all round the table for a cannon, and when he tried long pots as often as not he got a pair of breeches. By the time he had taken a fiver apiece from us, I was sick of it.

‘What, had enough?’ cries he, cock-a-hoop. ‘Come on, Flash, where’s your spirit? I’ll play you any cramp game you like – shell-out, skittle pool, pyramids, caroline, doublet or go-back.5 What d’ye say? Come on, Speed, you’re game, I see.’

So Speed, the ass, played him again, while I mooched about in no good humour, waiting for them to finish. And it chanced that my eye fell on a game that was going on at a corner table, and I stopped to watch.

It was a flat-catching affair, one of the regular sharks fleecing a novice, and I settled down to see what fun there would be when the sheep realised he was being sheared. I had noticed him while we were playing with Cutts – a proper-looking mamma’s boy with a pale, delicate face and white hands, who looked as though he’d be more at home handing cucumber sandwiches to Aunt Jane than pushing a cue. He couldn’t have been more than eighteen, but I’d noticed his clothes were beautifully cut, although hardly what you’d call pool-room fashion; more like Sunday in the country. But there was money about him, and all told he was the living answer to a billiard-rook’s prayer.

They were playing pyramids, and the shark, a grinning specimen with ginger whiskers, was fattening his lamb for the kill. You may not know the game, but there are fifteen colours, and you try to pocket them one after the other, like pool, usually for a stake of a bob a time. The lamb had put down eight of them, and the shark three, exclaiming loudly at his ill luck, and you could see the little chap was pretty pleased with himself.

‘Only four balls left!’ cries the shark. ‘Well, I’m done for; my luck’s dead out, I can see. Tell you what, though; it’s bound to change; I’ll wager a sovereign on each of the last four.’

You or I would know that this was the time to put up your cue and say good evening, before he started making the balls advance in column of route dressed from the front, and even the little greenhorn thought hard about it; but hang it, you could see him thinking, I’ve potted eight out of eleven – surely I’ll get at least two of those remaining.

So he said very well, and I waited to see the shark slam the four balls away in as many shots. But he had weighed up his man’s purse, and decided on a really good plucking, and after pocketing the first ball with a long double that made the greenhorn’s jaw drop, the shark made a miscue on his next stroke. Now when you foul at pyramids, one of the potted balls is put back on the table, so there were four still to go at. So it went on, the shark potting a ball and collecting a quid, and then fouling – damning his own clumsiness, of course – so that the ball was re-spotted again. It could go on all night, and the look of horror on the little greenhorn’s face was a sight to see. He tried desperately to pot the balls himself, but somehow he always found himself making his shots from a stiff position against the cushion, or with the four colours all lying badly; he could make nothing of it. The shark took fifteen pounds off him before dropping the last ball – off three cushions, just for swank – and then dusted his fancy weskit, thanked the flat with a leer, and sauntered off whistling and calling the waiter for champagne.

The little gudgeon was standing woebegone, holding his limp purse. I thought of speeding him on his way with a taunt or two, and then I had a sudden bright idea.

‘Cleaned out, Snooks?’ says I. He started, eyed me suspiciously, and then stuck his purse in his pocket and turned to the door.

‘Hold on,’ says I. ‘I’m not a Captain Sharp; you needn’t run away. He rooked you properly, didn’t he?’

He stopped, flushing. ‘I suppose he did. What is it to you?’

‘Oh, nothing at all. I just thought you might care for a drink to drown your sorrows.’

He gave me a wary look; you could see him thinking, here’s another of them.

‘I thank you, no,’ says he, and added: ‘I have no money left whatever.’

‘I’d be surprised if you had,’ says I, ‘but fortunately I have. Hey, waiter.’

The boy was looking nonplussed, as though he wanted to go out into the street and weep over his lost fifteen quid, but at the same time not averse to some manly comfort from this cheery chap. Even Tom Hughes allowed I could charm when I wanted to, and in two minutes I had him looking into a brandy glass, and soon after that we were chatting away like old companions.

He was a foreigner, doing the tour, I gathered, in the care of some tutor from whom he had managed to slip away to have a peep at the flesh-pots of London. The depths of depravity for him, it seemed, was a billiard-room, so he had made for this one and been quickly inveigled and fleeced.

‘At least it has been a lesson to me,’ says he, with that queer formal gravity which a man so often uses in speaking a language not his own. ‘But how am I to explain my empty purse to Dr Winter? What will he think?’

‘Depends how coarse an imagination he’s got,’ says I. ‘You needn’t fret about him; he’ll be so glad to get you back safe and sound, I doubt if he’ll ask too many questions.’

‘That is true,’ says my lad, thoughtfully. ‘He will fear for his own position. Why, he has been a negligent guardian, has he not?’

‘Dam’ slack,’ says I. ‘The devil with him. Drink up, boy, and confusion to Dr Winter.’

You may wonder why I was buying drink and being pleasant to this flat; it was just a whim I had dreamed up to be even with Cutts. I poured a little more into my new acquaintance, and got him quite merry, and then, with an eye on the table where Cutts was trimming up Speed, and gloating over it, I says to the youth:

‘I tell you what, though, my son, it won’t do for the sporting name of Old England if you creep back home without some credit. I can’t put the fifteen sovs back in your pocket, but I’ll tell you what – just do as I tell you, and I’ll see that you win a game before you walk out of this hall.’

‘Ah, no – that, no,’ says he. ‘I have played enough; once is sufficient – besides, I tell you, I have no more money.’

‘Gammon,’ says I. ‘Who’s talking about money? You’d like to win a match, wouldn’t you?’

‘Yes, but …’ says he, and the wary look was back in his eye. I slapped him on the knee, jolly old Flash.

‘Leave it to me,’ says I. ‘What, man, it’s just in fun. I’ll get you a game with a pal of mine, and you’ll trim him up, see if you don’t.’

‘But I am the sorriest player,’ cries he. ‘How can I beat your friend?’

‘You ain’t as bad as you think you are,’ says I. ‘Depend on it. Now just sit there a moment.’

I slipped over to one of the markers whom I knew well. ‘Joe,’ says I, ‘give me a shaved ball, will you?’

‘What’s that, cap’n?’ says he. ‘There’s no such thing in this ’ouse.’

‘Don’t fudge me, Joe. I know better. Come on, man, it’s just for a lark, I tell you. No money, no rooking.’

He looked doubtful, but after a moment he went behind his counter and came back with a set of billiard pills. ‘Spot’s the boy,’ says he. ‘But mind, Cap’n Flashman, no nonsense, on your honour.’

‘Trust me,’ says I, and went back to our table. ‘Now, Sam Snooks, just you pop those about for a moment.’ He was looking quite perky, I noticed, what with the booze and, I suspect, a fairly bouncy little spirit under his mamma’s boy exterior. He seemed to have forgotten his fleecing at any rate, and was staring about him at the fellows playing at nearby tables, some in flowery weskits and tall hats and enormous whiskers, others in the new fantastic coloured shirts that were coming in just then, with death’s heads and frogs and serpents all over them; our little novice was drinking it all in, listening to the chatter and laughter, and watching the waiters weave in and out with their trays, and the markers calling off the breaks. I suppose it’s something to see, if you’re a bumpkin.

I went over to where Cutts was just demolishing Speed, and as the pink ball went away, I says:

‘There’s no holding you tonight, Cutts, old fellow. Just my luck, when my eye’s out, to meet first you and then that little terror in the corner yonder.’

‘What, have you been browned again?’ says he, looking round. ‘Oh, my stars, never by that, though, surely? Why, he’s not out of leading-strings, by the looks of him.’

‘Think so?’ says I. ‘He’ll give you twenty in the hundred, any day.’

Well, of course, that settled it, with a conceited pup like Cutts; nothing would do but he must come over, with his toadies in his wake, making great uproar and guffawing, and offer to make a game with my little greenhorn.

‘Just for love, mind,’ says I, in case Joe the marker was watching, but Cutts wouldn’t have it; insisted on a bob a point, and I had to promise to stand good for my man, who shied away as soon as cash was mentioned. He was pretty tipsy by now, or I doubt if I’d have got him to stay at the table, for he was a timid squirt, even in drink, and the bustling and catcalling of the fellows made him nervous. I rolled him the plain ball, and away they went, Cutts chalking his cue with a flourish and winking to his pals.

You’ve probably never seen a shaved ball used – but then, you wouldn’t know it if you had. The trick is simple; your sharp takes an ordinary ball beforehand, and gets a craftsman to peel away just the most delicate shaving of ivory from one side of it; some clumsy cheats try to do it by rubbing it with fine sand-paper, but that shows up like a whore in church. Then, in the game, he makes certain his opponent gets the shaved ball, and plays away. The flat never suspects a thing, for a carefully shaved ball can’t be detected except with the very slowest of slow shots, when it will waver ever so slightly just before it stops. But of course, even with fast shots it goes off the true just a trifle, and in as fine a game as billiards or pool, where precision is everything, a trifle is enough.

It was for Cutts, anyhow. He missed cannons by a whisker, his winning hazards rattled in the jaws of the pocket and stayed out, his losers just wouldn’t drop, and when he tried a jenny he often missed the red altogether. He swore blind and fumed, and I said, ‘My, my, damme, that was close, what?’ and my little greenhorn plugged away – he was a truly shocking player, too – and slowly piled up the score. Cutts couldn’t fathom it, for he knew he was hitting his shots well, but nothing would go right.

I helped him along by suggesting he was watching the wrong ball – a notion which is sure death, once it has been put in a player’s mind – and he got wild and battered away recklessly, and my youngster finally ran out an easy winner, by thirty points.

I was interested to notice he got precious cocky at this. ‘Billiards is not a difficult game, after all,’ says he, and Cutts ground his teeth and began to count out his change. His fine chums, of course, were bantering him unmercifully – which was all I’d wanted in the first place.

‘Better keep your cash to pay for lessons, Cutts, my boy,’ says I. ‘Here, Speed, take our young champion for a drink.’ And when they had gone off to the bar I grinned at Cutts. ‘I’d never have guessed it – with whiskers like yours.’

‘Guessed what, damn you, you funny flash man?’ says he, and I held up the spot ball between finger and thumb.

‘Never have guessed you’d have such a close shave,’ says I. ‘’Pon my soul, you ain’t fit to play with rooks like our little friend. You’d better take up hoppity, with old ladies.’

With a sudden oath he snatched the ball from me, set it on the cloth, and played it away. He leaned over, eyes goggling, as it came to rest, cursed foully, and then dashed it on to the floor.

‘Shaved, by God! Curse you, Flashman – you’ve sharped me, you and that damned little diddler! Where is the little toad – I’ll have him thrashed and flung out for this!’

‘Hold your wind,’ says I, while his pals fell against each other and laughed till they cried. ‘He didn’t know anything about it. And you ain’t sharped – I’ve told you to keep your money, haven’t I?’ I gave him a mocking leer. ‘“Any cramp game you like,” eh? Skittle pool, go-back – but not billiards with little flats from the nursery.’ And I left him thoroughly taken down, and went off to find Speed.

You’ll think this a very trivial revenge, no doubt, but then I’m a trivial chap – and I know the way under the skin of muffins like Cutts, I hope. What was it Hughes said – Flashman had a knack of knowing what hurt, and by a cutting word or look could bring tears to the eyes of people who would have laughed at a blow? Something like that; anyway, I’d taken the starch out of friend Cutts, and spoiled his evening, which was just nuts to me.

I took up with Speed and the greenhorn, who was now waxing voluble in the grip of booze, and off we went. I thought it would be capital sport to take him along to one of the accommodation houses in Haymarket, and get him paired off with a whore in a galloping wheelbarrow race, for it was certain he’d never been astride a female in his life, and it would have been splendid to see them bumping across the floor together on hands and knees towards the winning post. But we stopped off for punch on the way, and the little snirp got so fuddled he couldn’t even walk. We helped him along, but he was maudlin, so we took off his trousers in an alley off Regent Street, painted his arse with blacking which we bought for a penny on the way, and then shouted, ‘Come on, peelers! Here’s the scourge of A Division waiting to set about you! Come on and be damned to you!’ And as soon as the bobbies hove in sight we cut, and left them to find our little friend, nose down in the gutter with his black bum sticking up in the air.

I went home well pleased that night, only wishing I could have been present when Dr Winter came face to face again with his erring pupil.

And that night’s work changed my life, and preserved India for the British Crown – what do you think of that? It’s true enough, though, as you’ll see.

However, the fruits didn’t appear for a few days after that, and in the meantime another thing happened which also has a place in my story. I renewed an old acquaintance, who was to play a considerable part in my affairs over the next few months – and that was full of consequence, too, for him, and me, and history.

I had spent the day keeping out of Paget’s way at the Horse Guards, and chatting part of the time, I remember, with Colonel Colt, the American gun expert, who was there to give evidence before the select committee on fire-arms.6 (I ought to remember our conversation, but I don’t, so it was probably damned dull and technical.) Afterwards, however, I went up to Town to meet Elspeth in the Ride, and take her on to tea with one of her Mayfair women.

She was side-saddling it up the Ride, wearing her best mulberry rig and a plumed hat, and looking ten times as fetching as any female in view. But as I trotted up alongside, I near as not fell out of my saddle with surprise, for she had a companion with her, and who should it be but my Lord Haw-Haw himself, the Earl of Cardigan.

I don’t suppose I had exchanged a word with him – indeed, I had hardly seen him, and then only at a distance – since he had packed me off to India fourteen years before. I had loathed the brute then, and time hadn’t softened the sentiment; he was the swine who had kicked me out of the Cherrypickers for (irony of ironies) marrying Elspeth, and committed me to the horrors of the Afghan campaign.fn1 And here he was, getting spoony round my wife, whom he had affected to despise once on a day for her lowly origins. And spooning to some tune, too, by the way he was leaning confidentially across from his saddle, his rangy old boozy face close to her blonde and beautiful one, and the little slut was laughing and looking radiant at his attentions.

She caught my eye and waved, and his lordship looked me over in his high-nosed damn-you way which I remembered so well. He would be in his mid-fifties by now, and it showed; the whiskers were greying, the gooseberry eyes were watery, and the legions of bottles he had consumed had cracked the veins in that fine nose of his. But he still rode straight as a lance, and if his voice was wheezy it had lost nothing of its plunger drawl.

‘Haw, haw,’ says he, ‘it is Fwashman, I see. Where have you been sir? Hiding away these many years, I daresay, with this lovely lady. Haw-haw. How-de-do, Fwashman? Do you know, my dear’ – this to Elspeth, damn his impudence – ‘I decware that this fine fellow, your husband, has put on fwesh alarmingly since last I saw him. Haw-haw. Always was too heavy for a wight dwagoon, but now – pwepostewous! You feed him too well, my dear! Haw-haw!’

It was a damned lie, of course, no doubt designed to draw a comparison with his own fine figure – scrawny, some might have thought it. I could have kicked his lordly backside, and given him a piece of my mind.

‘Good day, milord,’ says I, with my best toady smile. ‘May I say how well your lordship is looking? In good health, I trust.’

‘Thank’ee,’ says he, and turning to Elspeth: ‘As I was saying, we have the vewy finest hunting at Deene. Spwendid sport, don’t ye know, and specially wecommended for young wadies wike yourself. You must come to visit – you too, Fwashman. You wode pwetty well, as I wecollect. Haw-haw.’

‘You honour me with the recollection, milord,’ says I, wondering what would happen if I smashed him between the eyes. ‘But I—’

‘Yaas,’ says he, turning languidly back to Elspeth. ‘No doubt your husband has many duties – in the ordnance, is it not, or some such thing? Haw-haw. But you must come down, my dear, with one of your fwiends, for a good wong stay, what? The faiwest bwossoms bwoom best in countwy air, don’t ye know? Haw-haw.’ And the old scoundrel had the gall to lean over and pat her hand.

She, the little ninny, was all for it, giving him a dazzling smile and protesting he was too, too kind – this aged satyr who was old enough to be her father and had vice leering out of every wrinkle in his face. Of course, where climbing little snobs like Elspeth are concerned, there ain’t such a thing as an ugly peer of the realm, but even she could surely have seen how grotesque his advances were. Of course, women love it.

‘How splendid to see you two old friends together again, after such a long time, is it not, Lord Cardigan? Why, I declare I have never seen you in his lordship’s company, Harry! Such a dreadfully long time it must have been!’ Babbling, you see, like the idiot she was. I’m not sure she didn’t say something about ‘comrades in arms’. ‘You must call upon us, Lord Cardigan, now that you and Harry have met again. It will be so fine, will it not, Harry?’

‘Yaas,’ says he. ‘I may call,’ with a look at me that said he would never dream of setting foot in any hovel of mine. ‘In the meantime, my dear, I shall wook to see you widing hereabouts. Haw-haw. I dewight to see a female who wides so gwacefully. Decidedwy you must come to Deene. Haw-haw.’ He took off his hat to her, bowing from the waist – and a Polish hussar couldn’t have done it better, damn him. ‘Good day to you, Mrs Fwashman.’ He gave me the merest nod, and cantered off up the Ride, cool as you please.

‘Is he not wonderfully condescending, Harry? Such elegant manners – but of course, it is natural in one of such noble breeding. I am sure if you spoke to him, my dear, he would be ready to give the most earnest consideration to finding a place for you – he is so kind, despite his high station. Why, he has promised me almost any favour I care to ask – Harry, whatever is the matter? Why are you swearing – oh, my love, no, people will hear! Oh!’

Of course, swearing and prosing were both lost on Elspeth; when I had vented my bile against Cardigan I tried to point out to her the folly of accepting the attentions of such a notorious roué, but she took this as mere jealousy on my part – not jealousy of a sexual kind, mark you, but supposedly rooted in the fact that here she was climbing in the social world, spooned over by peers, while I was labouring humbly in an office like any Cratchit, and could not abide to see her ascending so far above me. She even reminded me that she was a baron’s daughter, at which I ground my teeth and hurled a boot through our bedroom window, she burst into tears, and ran from the room to take refuge in a broom cupboard, whence she refused to budge while I hammered on the panels. She was terrified of my brutal ways, she said, and feared for her life, so I had to go through the charade of forcing open the door and rogering her in the cupboard before peace was restored. (This was what she had wanted since the quarrel began, you see; very curious and wearing our domestic situation was, but strangely enjoyable, too, as I look back on it. I remember how I carried her to the bedroom afterwards, she nibbling at my ear with her arms round my neck, and at the sight of the broken window we collapsed giggling and kissing on the floor. Aye, married bliss. And like the fool I was I clean forgot to forbid her to talk to Cardigan again.)

But in the next few days I had other things to distract me from Elspeth’s nonsense; my jape in the pool-room with the little greenhorn came home to roost, and in the most unexpected way. I received a summons from my Lord Raglan, of all people.

You will know all about him, no doubt. He was the ass who presided over the mess we made in the Crimea, and won deathless fame as the man who murdered the Light Brigade. He should have been a parson, or an Oxford don, or a waiter, for he was the kindliest, softest-voiced old stick who ever spared a fellow-creature’s feelings – that was what was wrong with him, that he couldn’t for the life of him say an unkind word, or set anyone down. And this was the man who was the heir to Wellington – as I sat in his office, looking across at his kindly old face, with its rumpled white hair and long nose, and found my eyes straying to the empty right sleeve tucked into his breast, he looked so pathetic and frail, I shuddered inwardly. Thank God, thinks I, that I won’t be in this chap’s campaign.

They had just made him Commander-in-Chief, after years spent bumbling about on the Board of Ordnance, and he was supposed to be taking matters in hand for the coming conflict. So you may guess that the matter on which he had sent for me was one of the gravest national import – Prince Albert, our saintly Bertie the Beauty, wanted a new aide-de-camp, or equerry, or toad-eater-extraordinary, and nothing would do but our new Commander must set all else aside to see the thing was done properly.

Mark you, I’d no time to waste marvelling over the fatuousness of this kind of mismanagement; it was nothing new in our army, anyway, and still isn’t, from all I can see. Ask any commander to choose between toiling over the ammunition returns for a division fighting for its life, and taking the King’s dog for a walk, and he’ll be out there in a trice, bawling ‘Heel, Fido!’ No, I was too much knocked aback to learn that I, Captain Harry Flashman, former Cherrypicker and erstwhile hero of the country, of no great social consequence and no enormous means or influence, should even be considered to breathe the lordly air of the court. Oh, I had my fighting reputation, but what’s that, when London is bursting with pink-cheeked viscounts with cleft palates and long pedigrees? My great-great-great-grandpapa wasn’t even a duke’s bastard, so far as I know.

Raglan approached the thing in his usual roundabout way, by going through a personal history which his minions must have put together for him.

‘I see you are thirty-one years old, Flashman,’ says he. ‘Well, well, I had thought you older – why, you must have been only – yes, nineteen, when you won your spurs at Kabul. Dear me! So young. And since then you have served in India, against the Sikhs, but have been on half pay these six years, more or less. In that time, I believe, you have travelled widely?’

Usually at high speed, thinks I, and not in circumstances I’d care to tell your lordship about. Aloud I confessed to acquaintance with France, Germany, the United States, Madagascar, West Africa, and the East Indies.

‘And I see you have languages – excellent French, German. Hindoostanee, Persian – bless my soul! – and Pushtu. Thanks of Parliament in ’42, Queen’s Medal – well, well, these are quite singular accomplishments, you know.’ And he laughed in his easy way. ‘And apart from Company service, you were formerly, as I apprehend, of the 11th Hussars. Under Lord Cardigan. A-ha. Well, now, Flashman, tell me, what took you to the Board of Ordnance?’

I was ready for that one, and spun him a tale about improving my military education, because no field officer could know too much, and so on, and so on …

‘Yes, that is very true, and I commend it in you. But you know, Flashman, while I never dissuade a young man from studying all aspects of his profession – which indeed, my own mentor, the Great Duke, impressed on us, his young men, as most necessary – still, I wonder if the Ordnance Board is really for you.’ And he looked knowing and quizzical, like someone smiling with a mouthful of salts. His voice took on a deprecatory whisper. ‘Oh, it is very well, but come, my boy, it cannot but seem – well, beneath, a little beneath, I think, a man whose career has been as, yes, brilliant as your own. I say nothing against the Ordnance – why, I was Master-General for many years – but for a young blade, well-connected, highly regarded …?’ He wrinkled his nose at me. ‘Is it not like a charger pulling a cart? Of course it is. Manufacturers and clerks may be admirably suited to deal with barrels and locks and rivets and, oh, dimensions, and what-not, but it is all so mechanical, don’t you agree?’

Why couldn’t the old fool mind his own business? I could see where this was leading – back to active service and being blown to bits in Turkey, devil a doubt. But who contradicts a Commander-in-Chief?

‘I think it a most happy chance,’ he went on, ‘that only yesterday His Royal Highness Prince Albert’ – he said it with reverence – ‘confided to me the task of finding a young officer for a post of considerable delicacy and importance. He must, of course, be well-born – your mother was Lady Alicia Paget, was she not? I remember the great pleasure I had in dancing with her, oh, how many years ago? Well, well, it is no matter. A quadrille, I fancy. However, station alone is not sufficient in this case, or I confess I should have looked to the Guards.’ Well, that was candid, damn him. ‘The officer selected must also have shown himself resourceful, valiant, and experienced in camp and battle. That is essential. He must be young, of equable disposition and good education, unblemished, I need not say, in personal reputation’ – God knows how he’d come to pick on me, thinks I, but he went on: ‘– and yet a man who knows his world. But above all – what our good old Duke would call “a man of his hands”.’ He beamed at me. ‘I believe your name must have occurred to me at once, had His Highness not mentioned it first. It seems our gracious Queen had recollected you to him.’ Well, well, thinks I, little Vicky remembers my whiskers after all these years. I recalled how she had mooned tearfully at me when she pinned my medal on, back in ’42 – they’re all alike you know, can’t resist a dashing boy with big shoulders and a trot-along look in his eye.

‘So I may now confide in you,’ he went on, ‘what this most important duty consists in. You have not heard, I daresay, of Prince William of Celle? He is one of Her Majesty’s European cousins, who has been visiting here some time, incognito, studying our English ways preparatory to pursuing a military career in the British Army. It is his family’s wish that when our forces go overseas – as soon they must, I believe – he shall accompany us, as a member of my staff. But while he will be under my personal eye, as it were, it is most necessary that he should be in the immediate care of the kind of officer I have mentioned – one who will guide his youthful footsteps, guard his person, shield him from temptation, further his military education, and supervise his physical and spiritual welfare in every way.’ Raglan smiled. ‘He is very young, and a most amiable prince in every way; he will require a firm and friendly hand from one who can win the trust and respect of an ardent and developing nature. Well, Flashman, I have no doubt that between us we can make something of him. Do you not agree?’

By God, you’ve come to the right shop, thinks I. Flashy and Co., wholesale moralists, ardent and developing natures supervised, spiritual instruction guaranteed, prayers and laundry two bob extra. How the deuce had they picked on me? The Queen, of course, but did Raglan know what kind of a fellow they had alighted on? Granted I was a hero, but I’d thought my randying about and boozing and general loose living were well known – by George, he must know! Maybe, secretly, he thought that was a qualification – I’m not sure he wasn’t right. But the main point was, all my splendid schemes for avoiding shot and shell were out of court again; it was me for the staff, playing nursemaid to some little German pimp in the wilds of Turkey. Of all the hellish bad luck.

But of course I sat there jerking like a puppet, grinning foolishly – what else was there to do?

‘I think we may congratulate ourselves,’ the old idiot went on, ‘and tomorrow I shall take you to the Palace to meet your new charge. I congratulate you, Captain, and’ – he shook my hand with a noble smile – ‘I know you will be worthy of the trust imposed on you now, as you have been in the past. Good day to you, my dear sir. And now,’ I heard him say to his secretary as I bowed myself out, ‘there is this wretched war business. I suppose there is no word yet whether it has begun? Well, I do wish they would make up their minds.’

You have already guessed, no doubt, the shock that was in store for me at the Palace next day. Raglan took me along, we went through the rigmarole of flunkeys with brushes that I remembered from my previous visit with Wellington, and we were ushered into a study where Prince Albert was waiting for us. There was a reverend creature and a couple of the usual court clowns in morning dress looking austere in the background – and there, at Albert’s right hand, stood my little greenhorn of the billiard hall. The sight hit me like a ball in the leg – for a moment I stood stock-still while I gaped at the lad and he gaped at me, but then he recovered, and so did I, and as I made my deep bow at Raglan’s side I found myself wondering: have they got that blacking off his arse yet?

I was aware that Albert was speaking, in that heavy, German voice; he was still the cold, well-washed exquisite I had first met twelve years ago, with those frightful whiskers that looked as though someone had tried to pluck them and left off half way through. He was addressing me, and indicating a side-table on which a shapeless black object was lying.

‘’hat do you ’hink of the new hett for the Guards, Captain Flash-mann?’ says he.

I knew it, of course; the funny papers had been full of it, and mocking H.R.H., who had invented it. He was always inflicting monstrosities of his own creation on the troops, which Horse Guards had to tell him tactfully were not quite what was needed. I looked at this latest device, a hideous forage cap with long flaps,7 and said I was sure it must prove admirably serviceable, and have a very smart appearance, too. Capital, first-rate, couldn’t be better, God knows how someone hadn’t thought of it before.

He nodded smugly, and then says: ‘I un-erstend you were at Rugby School, Captain? Ah, but wait – a captain? That will hardly do, I think. A colonel, no?’ And he looked at Raglan, who said the same notion had occurred to him. Well, thinks I, if that’s how promotion goes, I’m all for it.

‘At Rugby School,’ repeated Albert. ‘That is a great English school, Willy,’ says he to the greenhorn, ‘of the kind which turns younk boys like yourself into menn like Colonel Flash-mann here.’ Well, true enough, I’d found it a fair mixture of jail and knocking-shop; I stood there trying to look like a chap who says his prayers in a cold bath every day.

‘Colonel Flash-mann is a famous soldier in England, Willy; although he is quite younk, he has vun – won – laurelss for brafery in India. You see? Well, he will be your friend and teacher, Willy; you are to mind all that he says, and obey him punctually and willingly, ass a soldier should. O-bedience is the first rule of an army, Willy, you understand?’

The lad spoke for the first time, darting a nervous look at me. ‘Yes, uncle Albert.’

‘Ver-ry good, then. You may shake hands with Colonel Flash-mann.’

The lad came forward hesitantly, and held out his hand. ‘How do you do?’ says he, and you could tell he had only lately learned the phrase.

‘You address Colonel Flash-mann, as “sir”, Willy,’ says Albert. ‘He is your superior officer.’

The kid blushed, and for the life of me I can’t think how I had the nerve to say it, with a stiff-neck like Albert, but the favour I won with this boy was going to be important, after all – you can’t have too many princely friends – and I thought a Flashy touch was in order. So I said:

‘With your highness’s permission, I think “Harry” will do when we’re off parade. Hullo, youngster.’

The boy looked startled, and then smiled, the court clowns started to look outraged, Albert looked puzzled, but then he smiled, too, and Raglan hum-hummed approvingly. Albert said:

‘There, now, Willy, you have an English comrade. You see? Very goot. You will find there are none better. And now, you will go with – with “Harry”’ – he gave a puffy smile, and the court clowns purred toadily, – ‘and he will instruct you in your duties.’