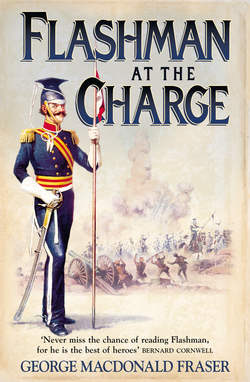

Читать книгу Flashman at the Charge - George Fraser MacDonald - Страница 11

ОглавлениеI’ve been about courts a good deal in my misspent career, and by and large I bar royalty pretty strong. They may be harmless enough folk in themselves, but they attract a desperate gang of placemen and hangers-on, and in my experience, the closer you get to the throne, the nearer you may finish up to the firing-line. Why, I’ve been a Prince Consort myself, and had half the cutthroats of Europe trying to assassinate me,fn1 and in my humbler capacities – as chief of staff to a White Rajah, military adviser and chief stud to that black she-devil Ranavalona, and irregular emissary to the court of King Gezo of Dahomey, long may he rot – I’ve usually been lucky to come away with a well-scarred skin. And my occasional attachments to the Court of St James’s have been no exception; nursemaiding little Willy was really the most harrowing job of the lot.

Mind you, the lad was amiable enough in himself, and he took to me from the first.

‘You are a brick,’ he told me as soon as we were alone. ‘Is that not the word? When I saw you today, I was sure you would tell them of the billiard place, and I would be disgraced. But you said nothing – that was to be a true friend.’

‘Least said, soonest mended,’ says I. ‘But whatever did you run away for that night? – why, I’d have seen you home right enough. We couldn’t think what had become of you.’

‘I do not know myself,’ says he. ‘I know that some ruffians set upon me in a dark place, and … stole some of my clothes.’ He blushed crimson, and burst out: ‘I resisted them fiercely, but they were too many for me! And then the police came, and Dr Winter had to be sent for, and – oh! there was such a fuss! But you were right – he was too fearful of his own situation to inform on me to their highnesses. However, I think it is by his insistence that a special guardian has been appointed for me.’ He gave me his shy, happy smile. ‘What luck that it should be you!’

Lucky, is it, thinks I, we’ll see about that. We’d be off to the war, if ever the damned thing got started – but when I thought about it, it stood to reason they wouldn’t risk Little Willy’s precious royal skin very far, and his bear-leader should be safe enough, too. All I said was:

‘Well, I think Dr Winter’s right; you need somebody and a half to look after you, for you ain’t safe on your own hook. So look’ee here – I’m an easy chap, as anyone’ll tell you, but I’ll stand no shines, d’ye see? Do as I tell you, and we’ll do famously, and have good fun, too. But no sliding off on your own again – or you’ll find I’m no Dr Winter. Well?’

‘Very well, sir – Harry,’ says he, prompt enough, but for all his nursery look, I’ll swear he had a glitter in his eye.

We started off on the right foot, with a very pleasant round of tailors and gunsmiths and bootmakers and the rest, for the child hadn’t a stick or stitch for a soldier, and I aimed to see him – and myself – bang up to the nines. The luxury of being toadied through all the best shops, and referring the bills to Her Majesty, was one I wasn’t accustomed to, and you may believe I made the most of it. At my tactful suggestion to Raglan, we were both gazetted in the 17th, who were lancers – no great style as a regiment, perhaps, but I knew it would make Cardigan gnash his elderly teeth when he heard of it, and I’d been a lancer myself in my Indian days. Also, to my eye it was the flashiest rigout in the whole light cavalry, all blue and gold – the darker the better, when you’ve got the figure for it, which of course I had.

Anyway, young Willy clapped his hands when he saw himself in full fig, and ordered another four like it – no one spends like visiting royalty, you know. Then he had to be horsed, and armed, and given lashings of civilian rig, and found servants, and camp gear – and I spent a whole day on that alone. If we were going campaigning, I meant to make certain we did it with every conceivable luxury – wine at a sovereign the dozen, cigars at ten guineas the pound, preserved foods of the best, tip-top linen, quality spirits by the gallon, and all the rest of the stuff that you need if you’re going to fight a war properly. Last of all I insisted on a lead box of biscuits – and Willy cried out with laughter.

‘They are ship’s biscuits – what should we need those for?’

‘Insurance, my lad,’ says I. ‘Take ’em along, and it’s odds you’ll never need them. Leave ’em behind, and as sure as shooting you’ll finish up living off blood-stained snow and dead mules.’ It’s God’s truth, too.

‘It will be exciting!’ cries he, gleefully. ‘I long to be off!’

‘Just let’s hope you don’t find yourself longing to be back,’ says I, and nodded at the mountain of delicacies we had ordered. ‘That’s all the excitement we want.’

His face fell at that, so I cheered him up with a few tales of my own desperate deeds in Afghanistan and elsewhere, just to remind him that a cautious campaigner isn’t necessarily a milksop. Then I took him the rounds, of clubs, and the Horse Guards, and the Park, presented him to anyone of consequence whom I felt it might be useful to toady – and, by George, I had no shortage of friends and fawners when the word got about who he was. I hadn’t seen so many tuft-hunters since I came home from Afghanistan.

You may imagine how Elspeth took the news, when I notified her that Prince Albert had looked me up and given me a Highness to take in tow. She squealed with delight – and then went into a tremendous flurry about how we must give receptions and soirées in his honour, and Hollands would have to provide new curtains and carpet, and extra servants must be hired, and who should she invite, and what new clothes she must have – ‘for we shall be in everyone’s eye now, and I shall be an object of general remark whenever I go out, and everyone will wish to call – oh, it will be famous! – and we shall be receiving all the time, and—’

‘Calm yourself, my love,’ says I. ‘We shan’t be receiving – we shall be being received. Get yourself a few new duds, by all means, if you’ve room for ’em, and then – wait for the pasteboards to land on the mat.’

And they did, of course. There wasn’t a hostess in Town but was suddenly crawling to Mrs Flashman’s pretty feet, and she gloried in it. I’ll say that for her, there wasn’t an ounce of spite in her nature, and while she began to condescend most damnably, she didn’t cut anyone – perhaps she realised, like me, that it never pays in the long run. I was pretty affable myself, just then, and pretended not to hear one or two of the more jealous remarks that were dropped – about how odd it was that Her Majesty hadn’t chosen one of the purple brigade to squire her young cousin, not so much as Guardee even, but a plain Mr – and who the deuce were the Flashmans anyway?

But the press played up all right; The Times was all approval that ‘a soldier, not a courtier, has been entrusted with the grave responsibility entailed in the martial instruction of the young prince. If war should come, as it surely must if Russian imperial despotism and insolence try our patience further, what better guardian and mentor of His Highness could be found than the Hector of Afghanistan? We may assert with confidence – none.’ (I could have asserted with confidence, any number, and good luck to ’em.)

Even Punch, which didn’t have much to say for the Palace, as a rule, and loathed the Queen’s great brood of foreign relations like poison, had a cartoon showing me frowning at little Willy under a signpost of which one arm said ‘Hyde Park’ and the other ‘Honour and Duty’, and saying: ‘What, my boy, do you want to be a stroller or a soldier? You can’t be both if you march in step with me.’ Which delighted me, naturally, although Elspeth thought it didn’t make me look handsome enough.

Little Willy, in the meantime, was taking to all this excitement like a Scotchman to drink. Under a natural shyness, he was a breezy little chap, quick, eager to please, and good-natured; he could be pretty cool with anyone over-familiar, but he could charm marvellously when he wanted – as he did with Elspeth when I took him home to tea. Mind you, the man who doesn’t want to charm Elspeth is either a fool or a eunuch, and little Willy was neither, as I discovered on our second day together, as we were strolling up Haymarket – we’d been shopping for a pair of thunder-and-lightningsfn2 which he admired. It was latish afternoon, and the tarts were beginning to parade; little Willy goggled at a couple of painted princesses swaying by in all their finery, ogling, and then he says to me in a reverent whisper:

‘Harry – I say, Harry – those women – are they—’

‘Whores,’ says I. ‘Never mind ’em. Now, tomorrow, Willy, we must visit the Artillery Mess, I think, and see the guns limbering up in—’

‘Harry,’ says he. ‘I want a whore.’

‘Eh?’ says I. ‘You don’t want anything of the sort, my lad.’ I couldn’t believe my ears.

‘I do, though,’ says he, and damme, he was gaping after them like a satyr, this well-brought-up, Christian little princeling. ‘I have never had a whore.’

‘I should hope not!’ says I, quite scandalised. ‘Now, look here, young Willy, this won’t answer at all. You’re not to think of such things for a moment. I won’t have this … this lewdness. Why, I’m surprised at you! What would – why, what would Her Majesty have to say to such talk? Or Dr Winter, eh?’

‘I want a whore,’ says he, quite fierce. ‘I … I know it is wrong – but I don’t care! Oh, you have no notion what it is like! Since I was quite small, they have never even let me talk to girls – at home I was not even allowed to play with my little cousins at kiss-in-the-ring, or anything! They would not let me go to dancing-classes, in case it should excite me! Dr Winter is always lecturing me about thoughts that pollute, and the fearful punishments awaiting fornicators when they are dead, and accusing me of having carnal thoughts! Of course I have, the old fool! Oh, Harry, I know it is sinful – but I don’t care! I want one,’ says this remarkable youth dreamily, with a blissful look coming over his pure, chaste, boyish visage, ‘with long golden hair, and big, big round—’

‘Stop that this minute!’ says I. ‘I never heard the like!’

‘And she will wear black satin boots buttoning up to her thighs,’ he added, licking his lips.

I’m not often stumped, but this was too much. I know youth has hidden fires, but this fellow was positively ablaze. I tried to cry him down, and then reason with him, for the thought of his cutting a dash through the London bordellos and trotting back to Buckingham Palace with the clap, or some harpy pursuing him for blackmail, made my blood run cold. But it was no good.

‘If you say me nay,’ says he, quite determined, ‘I shall find one myself.’

I couldn’t budge him. So in the end I decided to let him have his way, and make sure there were no snags, and that it was done safe and quiet. I took him off to a very high-priced place I knew in St John’s Wood, swore the old bawd to secrecy, and stated the randy little pig’s requirements. She did him proud, too, with a strapping blonde wench – satin boots and all – and at the sight of her Willy moaned feverishly and pointed, quivering, like a setter. He was trying to clamber all over her almost before the door closed, and of course he made a fearful mess of it, thrashing away like a stoat in a sack, and getting nowhere. It made me quite sentimental to watch him – reminded me of my own ardent youth, when every coupling began with an eager stagger across the floor trying to disentangle one’s breeches from one’s ankles.

I had a brisk, swarthy little gypsy creature on the other couch, and we were finished and toasting each other in iced claret before Willy and his trollop had got properly buckled to. She was a knowing wench, however, and eventually had him galloping away like an archdeacon on holiday, and afterwards we settled down to a jolly supper of salmon and cold curry. But before we had reached the ices Willy was itching to be at grips with his girl again – where these young fellows get the fire from beats me. It was too soon for me, so while he walloped along I and the gypsy passed an improving few moments spying through a peephole into the next chamber, where a pair of elderly naval men were cavorting with three Chinese sluts. They were worse than Willy – it’s those long voyages, I suppose.

When we finally took our leave, Willy was fit to be blown away by the first puff of wind, but pleased as punch with himself.

‘You are a beautiful whore,’ says he to the blonde. ‘I am quite delighted with you, and shall visit you frequently.’ He did, too, and must have spent a fortune on her in tin, of which he had loads, of course. Being of a young and developing nature, as Raglan would have said, he tried as many other strumpets in the establishment as he could manage, but it was the blonde lass as often as not. He got quite spoony over her. Poor Willy.

So his military education progressed, and Raglan chided me for working him too hard. ‘His Highness appears quite pale,’ says he. ‘I fear you have him too much at the grindstone, Flashman. He must have some recreation as well, you know.’ I could have told him that what young Willy needed was a pair of locked iron drawers with the key at the bottom of the Serpentine, but I nodded wisely and said it was sometimes difficult to restrain a young spirit eager for instruction and experience. In fact, when it came to things like learning the rudiments of staff work and army procedure, Willy couldn’t have been sharper; my only fear was that he might become really useful and find himself being actively employed when we went east.

For we were going, there was now no doubt. War was finally declared at the end of March, in spite of Aberdeen’s dithering, and the mob bayed with delight from Shetland to Land’s End. To hear them, all we had to do was march into Moscow when we felt like it, with the Frogs carrying our packs for us and the cowardly Russians skulking away before Britannia’s flashing eyes. And mind you, I don’t say that the British Army and the French together couldn’t have done it – given a Wellington. They were sound at bottom, and the Russians weren’t. I’ll tell you something else, which military historians never realise: they call the Crimea a disaster, which it was, and a hideous botch-up by our staff and supply, which is also true, but what they don’t know is that even with all these things in the balance against you, the difference between hellish catastrophe and brilliant success is sometimes no greater than the width of a sabre blade, but when all is over no one thinks of that. Win gloriously – and the clever dicks forget all about the rickety ambulances that never came, and the rations that were rotten, and the boots that didn’t fit, and the generals who’d have been better employed hawking bedpans round the doors. Lose – and these are the only things they talk about.

But I’ll confess I saw the worst coming before we’d even begun. The very day war was declared Willy and I reported ourselves to Raglan at Horse Guards, and it took me straight back to the Kabul cantonment – all work and fury and chatter, and no proper direction whatever. Old Elphy Bey had sat picking at his nails and saying: ‘We must certainly consider what is best to be done’ while his staff men burst with impatience and spleen. You could see the germ of it here – Raglan’s ante-room was jammed with all sorts of people, Lucan, and Hardinge, and old Scarlett, and Anderson of the Ordnance, and there were staff-scrapers and orderlies running everywhere and saluting and bustling, and mounds of paper growing on the tables, and great consulting of maps (‘Where the devil is Turkey?’ someone was saying. ‘Do they have much rain there, d’ye suppose?’), but in the inner sanctum all was peace and amiability. Raglan was talking about neck-stocks, if I remember rightly, and how they should fasten well up under the chin.

We were kept well up to the collar, though, in the next month before our stout and thick-headed commander finally took his leave for the scene of war – Willy and I were not of his advance party, which pleased me, for there’s no greater fag than breaking in new ground. We were all day staffing at the Horse Guards, and Willy was either killing himself with kindness in St John’s Wood by night, or attending functions about Town, of which there were a feverish number. It’s always the same before the shooting begins – the hostesses go into a frenzy of gaiety, and all the spongers and civilians crawl out of the wainscoting braying with good fellowship because thank God they ain’t going, and the young plungers and green striplings roister it up, and their fiancées let ’em pleasure them red in the face out of pity, because the poor brave boy is off to the cannon’s mouth, and the dance goes on and the eyes grow brighter and the laughter shriller – and the older men in their dress uniforms look tired, and sip their punch by the fireplace and don’t say much at all.

Elspeth, of course, was in her element, dancing all night, laughing with the young blades and flirting with the old ones – Cardigan was still roostering about her, I noticed, with every sign of the little trollop’s encouragement. He’d got himself the Light Cavalry Brigade, which had sent a great groan through every hussar and lancer regiment in the army, and was even fuller of bounce than usual – his ridiculous lisp and growling ‘haw-haw’ seemed to sound everywhere you went, and he was full of brag about how he and his beloved Cherrypickers would be the élite advanced force of the army.

‘I believe they have given Wucan nominal charge of the cavalwy,’ I heard him tell a group of cronies at one party. ‘Well, I suppose they had to find him something, don’t ye know, and he may vewwy well look to wemounts, I daresay. Haw-haw. I hope poor Waglan does not find him too gweat an incubus. Haw-haw.’

This was Lucan, his own brother-in-law; they detested each other, which isn’t to be wondered at, since they were both detestable, Cardigan particularly. But his mighty lordship wasn’t having it all his own way, for the press, who hated him, revived the old jibe about his Cherrypickers’ tight pants, and Punch dedicated a poem to him called ‘Oh Pantaloons of Cherry’, which sent him wild. It was all gammon, really, for the pants were no tighter than anyone else’s – I wore ’em long enough, and should know – but it was good to see Jim the Bear roasting on the spit of popular amusement again. By God, I wish that spit had been a real one, with me to turn it.

It was a night in early May, I think, that Elspeth was bidden to some great drum in Mayfair to celebrate the first absolute fighting of the war, which had been reported a week or so earlier – our ships had bombarded Odessa, and broken half the windows in the place, so of course the fashionable crowd had to rave and riot in honour of the great victory.8 I don’t remember seeing Elspeth lovelier than she was that night, in a gown of some shimmering white satin stuff, and no jewels at all, but only flowers coiled in her golden hair. I would have had at her before she even set out, but she was all a-fuss tucking little Havvy into his cot – as though the nurse couldn’t do it ten times better – and was fearful that I would disarrange her appearance. I fondled her, and promised I would put her through the drill when she came home, but she damped this by telling me that Marjorie had bidden her stay the night, although it was only a few streets away, because the dancing would go on until dawn, and she would be too fatigued to return.

So off she fluttered, blowing me a kiss, and I snarled away to the Horse Guards, where I had to burn the midnight oil over sapper transports; Raglan had set out for Turkey leaving most of the work behind him, and those of us who were left were kept at it until three each morning. By the time we had finished, even Willy was too done up to fancy his usual nightly exercise with his Venus, so we sent out for some grub – it was harry and grass,fn3 I remember, which didn’t improve my temper – and then he went home.

I was tired and cranky, but I couldn’t think of sleep, somehow, so I went out and started to get drunk. I was full of apprehension about the coming campaign, and fed up with endless files and reports, and my head ached, and my shoes pinched, so I poured down the whistle-belly with brandy on top, and the inevitable result was that I finished up three parts tight in some cellar near Charing Cross. I thought of a whore, but didn’t want one – and then it struck me: I wanted Elspeth, and nothing else. By God, there was I, on the brink of another war, slaving my innards into knots, while she was tripping about in a Mayfair ballroom, laughing and darting chase-me glances at party-saunterers and young gallants, having a fine time for hours on end, and she hadn’t been able to spare me five minutes for a tumble! She was my wife, dammit, and it was too bad. I put away some more brandy while I considered the iniquity of this, and took a great drunken resolve – I would go round to Marjorie’s at once, surprise my charmer when she came to bed, and make her see what she had been missing all evening. Aye, that was it – and it was romantic, too, the departing warrior tupping up the girl he was going to leave behind, and she full of love and wistful longing and be-damned. (Drink’s a terrible thing.) Anyway, off I set west, with a full bottle in my pocket to see me through the walk, for it was after four, and there wasn’t even a cab to be had.

By the time I got to Marjorie’s place – a huge mansion fronting the Park, with every light ablaze – I was taking the width of the pavement and singing ‘Villikins and his Dinah’.9 The flunkeys at the door didn’t mind me a jot, for the house must have been full of foxed chaps and bemused females, to judge by the racket they were making. I found what looked like a butler, inquired the direction of Mrs Flashman’s chamber, and tramped up endless staircases, bouncing off the walls as I went. I found a lady’s maid, too, who put me on the right road, banged on a door, fell inside, and found the place was empty.

It was a lady’s bedroom, no error, but no lady, as yet. All the candles were burning, the bed was turned down, a fluffy little Paris night-rail which I recognised as one I’d bought my darling lay by the pillow, and her scent was in the air. I stood there sighing and lusting boozily; still dancing, hey? We’ll have a pretty little hornpipe together by and by, though – aha, I would surprise her. That was it; I’d hide, and bound out lovingly when she came up. There was a big closet in one wall, full of clothes and linen and what-not, so I toddled in, like the drunken, love-sick ass I was – you’d wonder at it, wouldn’t you, with all my experience? – settled down on something soft, took a last pull at my bottle – and fell fast asleep.

How long I snoozed I don’t know; not long, I think, for I was still well fuddled when I came to. It was a slow business, in which I was conscious of a woman’s voice humming ‘Allan Water’, and then I believe I heard a little laugh. Ah, thinks I, Elspeth; time to get up, Flashy. And as I hauled myself ponderously to my feet, and stood swaying dizzily in the dark of the closet, I was hearing vague confused sounds from the room. A voice? Voices? Someone moving? A door closing? I can’t be sure at all, but just as I blundered tipsily to the closet door, I heard a sharp exclamation which might have been anything from a laugh to a cry of astonishment. I stumbled out of the closet, blinking against the sudden glare of light, and my boisterous view halloo died on my lips.

It was a sight I’ll never forget. Elspeth was standing by the bed, naked except for her long frilled pantaloons; her flowers were still twined in her hair. Her eyes were wide with shock, and her knuckles were against her lips, like a nymph surprised by Pan, or centaurs, or a boozed-up husband emerging from the wardrobe. I goggled at her lecherously for about half a second, and then realised that we were not alone.

Half way between the foot of the bed and the door stood the 7th Earl of Cardigan. His elegant Cherrypicker pants were about his knees, and the front tail of his shirt was clutched up before him in both hands. He was in the act of advancing towards my wife, and from the expression on his face – which was that of a starving, apoplectic glutton faced with a crackling roast – and from other visible signs, his intention was not simply to compare birthmarks. He stopped dead at sight of me, his mottled face paling and his eyes popping, Elspeth squealed in earnest, and for several seconds we all stood stock-still, staring.

Cardigan recovered first, and looking back, I have to admire him. It was not an entirely new situation for me, you understand – I’d been in his shoes, so to speak, many a time, when husbands, traps, or bullies came thundering in unexpectedly. Reviewing Cardigan’s dilemma, I’d have whipped up my britches, feinted towards the window to draw the outraged spouse, doubled back with a spring on to the bed, and then been through the door in a twinkling. But not Lord Haw-Haw; his bearing was magnificent. He dropped his shirt, drew up his pants, threw back his head, looked straight at me, rasped: ‘Good night to you!’, turned about, and marched out, banging the door behind him.

Elspeth had sunk to the bed, making little sobbing sounds; I still stood swaying in disbelief, trying to get the booze out of my brain, wondering if this was some drunken nightmare. But it wasn’t, and as I glared at that big-bosomed harlot on the bed, all those ugly suspicions of fourteen years came flooding back, only now they were certainties. And I had caught her in the act at last, all but in the grip of that lustful, evil old villain! I’d just been in the nick of time to thwart him, too, damn him. And whether it was the booze, or my own rotten nature, the emotion I felt was not rage so much as a vicious satisfaction that I had caught her out. Oh, the rage came later, and a black despair that sometimes wounds me like a knife even now, but God help me, I’m an actor, I suppose, and I’d never had a chance to play the outraged husband before.

‘Well?’ It came out of me in a strangled yelp. ‘Well? What? What? Hey?’

I must have looked terrific, I suppose, for she dropped her squeaking and shuddering like a shot, and hopped over t’other side of the bed like a jack rabbit.

‘Harry!’ she squealed. ‘What are you doing here?’

It must have been the booze. I had been on the point of striding – well, staggering – round the bed to seize her and thrash her black and blue, but at her question I stopped, God knows why.

‘I was waiting for you! Curse you, you adulteress!’

‘In that cupboard?’

‘Yes, blast it, in that cupboard. By God, you’ve gone too far, you vile little slut, you! I’ll—’

‘How could you!’ So help me God, it’s what she said. ‘How could you be so inconsiderate and unfeeling as to pry on me in this way? Oh! I was never so mortified! Never!’

‘Mortified?’ cries I. ‘With that randy old rip sporting his beef in your bedroom, and you simpering naked at him? You – you shameless Jezebel! You lewd woman! Caught in the act, by George! I’ll teach you to cuckold me! Where’s a cane? I’ll beat the shame out of that wanton carcase, I’ll—’

‘It is not true!’ she cried. ‘It is not true! Oh, how can you say such a thing!’

I was glaring round for something to thrash her with, but at this I stopped, amazed.

‘Not true? Why, you infernal little liar, d’you think I can’t see? Another second and you’d have been two-backed-beasting all over the place! And you dare—’

‘It is not so!’ She stamped her foot, her fists clenched. ‘You are quite in the wrong – I did not know he was there until an instant before you came out of that cupboard! He must have come in while I was disrobing – Oh!’ And she shuddered. ‘I was taken quite unawares—’

‘By God, you were! By me! D’you think I’m a fool? You’ve been teasing that dirty old bull this month past, and I find him all but mounting you, and you expect me to believe—’ My head was swimming with drink, and I lost the words. ‘You’ve dishonoured me, damn you! You’ve—’

‘Oh, Harry, it is not true! I vow it is not! He must have stolen in, without my hearing, and—’

‘You’re lying!’ I shouted. ‘You were whoring with him!’

‘Oh, that is untrue! It is unjust! How can you think such a thing? How can you say it?’ There were tears in her eyes, as well there might be, and now her mouth trembled and drooped, and she turned her head away. ‘I can see,’ she sobbed, ‘that you merely wish to make this an excuse for a quarrel.’

God knows what I said in reply to that; sounds of rupture, no doubt. I couldn’t believe my ears, and then she was going on, sobbing away:

‘You are wicked to say such a thing! Oh, you have no thought for my feelings! Oh, Harry, to have that evil old creature steal up on me – the shock of it – oh, I thought to have died of fear and shame! And then you – you!’ And she burst into tears in earnest and flung herself down on the bed.

I didn’t know what to say, or do. Her behaviour, the way she had faced me, the fury of her denial – it was all unreal. I couldn’t credit it, after what I’d seen. I was full of rage and hate and disbelief and misery, but in drink and bewilderment I couldn’t reason straight. I tried to remember what I’d heard in the closet – had it been a giggle or a muted shriek? Could she be telling the truth? Was it possible that Cardigan had sneaked in on her, torn down his breeches in an instant, and been sounding the charge when she turned and saw him? Or had she wheedled him in, whispering lewdly, and been stripping for action when I rolled out? All this, in a confused brandy-laden haze, passed through my mind – as you may be sure it has passed since, in sober moments.

I was lost, standing there half-drunk. That queer mixture of shock and rage and exultation, and the vicious desire to punish her brutally, had suddenly passed. With any of my other women, I’d not even have listened, but taken out my spite on them with a whip – except on Ranavalona, who was bigger and stronger than I. But I didn’t care for the other women, you see. Brute and all that I am, I wanted to believe Elspeth.

Mind you, it was still touch and go whether I suddenly went for her or not; but for the booze I probably would have done. There was all the suspicion of the past, and the evidence of my eyes tonight. I stood, panting and glaring, and suddenly she swung up in a sitting position, like Andersen’s mermaid, her eyes full of tears, and threw out her arms. ‘Oh, Harry! Comfort me!’

If you had seen her – aye. It’s so easy, as none knows better than I, to sneer at the Pantaloons of this world, and the cheated wives, too, while the rakes and tarts make fools of them – ‘If only they knew, ho-ho!’ Perhaps they do, or suspect, but would just rather not let on. I don’t know why, but suddenly I was seated on the bed, with my arm round those white shoulders, while she sobbed and clung to me, calling me her ‘jo’ – it was that funny Scotch word, which she hadn’t used for years, since she had grown so grand, that made me believe her – almost.

‘Oh, that you should think ill of me!’ she sniffled. ‘Oh, I could die of shame!’

‘Well,’ says I, breathing brandy everywhere, ‘there he was, wasn’t he? By God! Well, I say!’ I suddenly seized her by the shoulders at arms’ length. ‘Do you—? No, by God! I saw him – and you – and – and—’

‘Oh, you are cruel!’ she cried. ‘Cruel, cruel!’ And then her arms went round my neck, and she kissed me, and I was sure she was lying – almost sure.

She sobbed away a good deal, and protested, and I babbled a great amount, no doubt, and she swore her honesty, and I didn’t know what to make of it. She might be true, but if she was a cheat and a liar and a whore, what then? Murder her? Thrash her? Divorce her? The first was lunatic, the second I couldn’t do, not now, and the third was unthinkable. With the trusts that old swine Morrison had left to tie things up, she controlled all the cash, and the thought of being a known cuckold living on my pay – well, I’m fool enough for a deal, but not for that. Her voice was murmuring in my ear, and all that naked softness was in my arms, and her fondling touch was reminding me of what I’d come here for in the first place, so what the devil, thinks I, first things first, and if you don’t pleasure her now till she faints, you’ll look back from your grey-haired evenings and wish you had. So I did.

I still don’t know – and what’s more I don’t care. But one thing only I was certain of that night – whoever was innocent, it wasn’t James Brudenell, Earl of Cardigan. I swore then inwardly, with Elspeth moaning through her kiss, that I would get even with that one. The thought of that filthy old goat trying to board Elspeth – it brought me out in a sweat of fury and loathing. I’d kill him, somehow. I couldn’t call him out – he’d hide behind the law, and refuse. Even worse, he might accept. And apart from the fact that I daren’t face him, man to man, there would have been scandal for sure. But somehow, some day, I would find a way.

We went to sleep at last, with Elspeth murmuring in my ear about what a mighty lover I was, recalling me in doting detail, and how I was at my finest after a quarrel. She was giggling drowsily about how we had made up our previous tiff, with me tumbling her in the broom closet at home, and what fun it had been, and how I’d said it was the most famous place for rogering, and then suddenly she asked, quite sharp:

‘Harry – tonight – your great rage at my misfortune was not all a pretence, was it? You did not – you are sure? – have some … some female in the cupboard?’

And damn my eyes, she absolutely got out to look. I don’t suppose I’ve cried myself to sleep since I was an infant, but it was touch and go then.