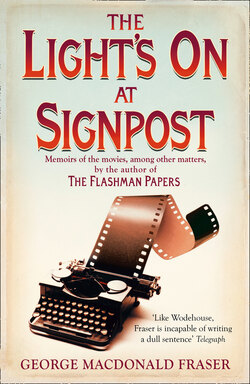

Читать книгу The Light’s On At Signpost - George MacDonald Fraser - Страница 5

FOREWORD

ОглавлениеOn the Isle of Man, where I am lucky enough to live, we have a saying: “The Light’s on at Signpost”. I’ll explain it presently; sufficient for the moment to say that it’s a catchphrase about the island’s famous TT (Tourist Trophy) race, the blue riband of world motor-cycling, and the nearest thing to the Roman circus since the hermit Telemachus got the shutters put up at the Colosseum. Riders come from the ends of the earth every June to compete on the thirty-seven-mile course, hurtling their machines over mountain, through town and village, round hairpin bends, along narrow, twisting stone-walled roads where the slightest misjudgment means death at 150 m.p.h., and on straights where they dice for position with each other and the Grim Reaper.

Inevitably there are deaths. Never a year passes but the TT or its companion races claim their victims, but still they keep coming, for it is the ultimate test of the road racer’s skill and daring, and the man who wins it, be he an Italian six-times victor with a mighty organisation behind him, or a humble garage mechanic, has nothing more to prove. He is the best in the world, and needs his head examined. But there it is: the TT will last as long as there are crazy men on machines – Germans, Italians, Irish, Swedes, Japanese, and every variety of Briton, including of course the Manx themselves.

That the race was world famous I had always known, but I was astonished when the late Steve McQueen, of Hollywood fame, who had never been to the island, talked of the TT course with the familiarity of old acquaintance. He was motor-cycle daft, to be sure, and even kept a bike, an old Indian, in the living-room of his penthouse in the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, and at some time, somehow, he had plainly informed himself about the course and its more celebrated features and hazards – the Verandah, Ramsey hairpin, Creg-ny-Baa, the Highlander where the bikes touch 190 m.p.h., and the rest – and I was properly impressed. He must come to the island, I said, and ride the course for himself: thirty-seven miles in less than twenty minutes.

He considered this in that calculating blue-eyed silence which captivated audiences round the world, smiled his famous tightlipped smile, and shook his head. “I’m forty-eight, remember. You can drive me round.”

I never had the chance. The light was already on for him at Signpost – and it is time to explain the saying. The TT is six circuits of the course, and each time a rider passes Signpost Corner, about a mile from the end of the circuit, a light flashes on at his slot on the grandstand scoreboard, to let spectators know he has almost finished a lap; when it lights up on his last lap, they know he is nearly home, the end is in sight, as it was for McQueen that afternoon when I said good-bye to him in Beverly Hills. Not long after, he was dead, and the movie in which he was to star, and which I had written, was never made. But whenever I hear that saying, which the Manx, with their Viking sense of humour, apply to life as well as to the TT, I think of him, chewing tobacco and spitting neatly into a china mug, making notes in his small, precise writing as we went through the script.

But that’s by the way for the moment, and I have dropped McQueen’s name at this point because I know that nothing grips the public, reading or viewing, like a film star – and we shall meet him again, and many others, later on. And another reason for introducing that fine Manx saying is that it applies to me, too; at seventy-seven, my light is on at Signpost – mind you, I hope to take my time over the last mile, metaphorically pushing my bike like those riders who run out of fuel within sight of the finish.

So I’m turning aside from the stories with which I’ve been earning a living for more than thirty years, to tell something of my own. In itself it may not interest more than a few people (those kind readers of my books and viewers of my screenplays who have written to me, perhaps), but apart from telling a bit of my own tale there is something else I want to do, not just for myself, but for all those others whose lights are on at Signpost, that huge majority of a generation who think as I do, but whose voices, on the rare occasions when they are raised, are lost in the clamour of the new millennium.

We are the old people (not the senior citizens or the timeously challenged, but the old people), and if I am accused of lunatic delusions of grandeur for presuming to speak for a generation, I can only retort that someone’s got to, because nobody has yet, not in full, and if we’re not careful we’ll all have gone down the pipe without today’s generation (or any other) getting a chance not just to hear our point of view, but perhaps to understand how and why we came to hold it. (Very well, my point of view, but I know that countless older people, and not a few younger ones, share it, for whenever I’ve had the chance to express it, in has come the tide of letters*, their purport being: Thank God somebody’s said it at last!)

It’s not a view that will find much favour with what are called the chattering classes, or the politically correct, or the self-appointed leaders of fashionable opinion, or so-called progressives, or liberals in general. (Actually, I’m a liberal myself, as well as a reactionary. I’m often surprised at just how liberal I can be; I’ll have to watch it.) It is a view that would have seemed perfectly normal and middle-of-the-road in my childhood, which makes it anathema today, when mis-called “Victorian values” are derided, and the permissive society has turned a scornful back on so many things that my generation respected and even venerated.

Such elderly hand-wringing is not new. Old folk in every generation since the Stone Age have seen huge changes, for better or worse, but none in Britain has seen the country so altered, so turned upside down, as we children born in the twenty years between the great world wars. In our adult lives Britain’s entire national spirit, its philosophy, its values and standards, have changed beyond belief, and probably no country on earth has experienced such a revolution in thought and outlook and behaviour in so short a space. Other lands have known what might seem to be greater upheavals, the result of wars and revolutions and invasions, but these do not compare with the experience of a country which passes in less than a lifetime from being the mightiest empire in history, governing a quarter of mankind, to being a feeble little offshore island whose so-called leaders have lost the will and the courage, indeed the ability, to govern at all.

This is not a lament for past imperial glory, although I can regret its inevitable passing, nor is it the raging of a die-hard Conservative. I loathe all political parties, which I regard as inventions of the devil, and if I inclined to vote Tory thirty years ago it was out of no admiration for them but simply to keep the incompetent wreckers out. We have no real political parties in the Isle of Man, thank heaven. Having had a parliament from a time when Westminster was a mere geographical swamp and had not yet become a moral one, we know what democracy is, which unfortunates in mainland Britain and the United States most certainly do not. It follows that we regard Westminster and Washington politics with revulsion and contempt.

But I am deeply concerned for the United Kingdom and its future. I can view the Signpost light with fair equanimity, I’ve looked death in the eye before, and now I have only a past, a little future, and no great care on my own account. But England and Scotland are my countries still, they are the lands where my children and grandchildren live, and I care most damnably about what lies ahead for them.

I look at the old country as it was in my youth, and as it is today, and frankly, to use a fine Scots word, I’m scunnered. I don’t despair altogether, because I have studied enough history to know that nothing is forever, but I and my generation have to shake our heads in disbelief, ask ourselves how it happened, and wonder if it can ever be repaired.

Who would have believed, fifty years ago, that by the end of the century it would have been deemed permissible, by the BBC of all people, to call the Queen “a bitch”, or that the foulest language and vilest pornography would be commonplace on television, or that we would have a government legislating to break up the United Kingdom, barely bothering to conceal their republican bent, guilty of atrocious war crimes, rashly declaring war on Muslim terrorism which did not threaten us, while crawling abjectly to the IRA and even assisting it by releasing murderers from prison, making a criminal out of an honest shopkeeper because he sold in pounds and ounces, and jailing for life a decent householder who dared to defend his home by shooting a burglar, refusing to take any effective action against violent crime, encouraging sexual perversion by lowering the age of consent and drug abuse by relaxing the law on cannabis, legislating for women to serve in the front line (while the gallant warriors of Westminster sit snug and safe), showing themselves dead to any notion of patriotism and even discouraging the use of the word “British”, falling over themselves to destroy our institutions simply because they are frightened of offending hostile aliens, seeking to deny the right of habeas corpus, pandering to the bigotry of black racists and encouraging racial strife by their timid stupidity, letting foreign interests wreck our farming and fishing industries, and allowing the children of those wonderful people who gave us Belsen and Dachau a vital say in making our law and undermining our constitution …

That’s what we fought two world wars for? What millions of precious British lives were lost for? That’s a land fit for heroes and their families?

This, of course, can all be patronisingly dismissed as the raving of a blimpish Right-wing* dinosaur. Not denied, though, because it is all patently true, and therefore poison to the politically correct. The very core of their philosophy is a refusal to accept truth, to look it squarely in the face, unpalatable as it may be. Political correctness is about denial, usually in the weasel circumlocutory jargon which distorts and evades and seldom stands up to honest analysis.

You conclude that I do not care for political correctness, but before they bury me under a tide of enlightened derision, there is a question which even a Liberal Democrat or Guardian reader might care to consider. It is this: why do I, and millions of my contemporaries, think the way we do? It doesn’t profit us. If all the wrongs that I have listed were righted tomorrow, it would bring us no material advantage, put nothing in our pockets, serve no ulterior purpose. Setting aside our care for our descendants, we are as disinterested as it is possible for people to be: we don’t seek election, or power, or wealth, we have no great personal ambitions left to realise or any compulsion to trample on our fellows’ fingers in a mad scramble up the ladder. For we are yesterday’s people, the over-the-hill gang, the light is really blazing for us at Signpost, and we seek no more than what we believe to be our country’s good.

Perhaps we have it closer to heart than younger folk do. Perhaps we value Britain more because we had to fight for it tooth and nail, and saved it and the world from evil and slavery and a new Dark Age, whereas later generations have had it handed to them on a plate, welfare-insulated and (sorry to have to say it) rather spoiled and not knowing how well off they are. But whatever of that, please believe that our motives are respectable, and our convictions honestly held. We are not without understanding; we know, from hard experience, that every generation thinks itself the repository of all wisdom, and imagines that the progress of mankind is one of continuous improvement, and that whatever may be wrong with today, things are still a hell of a lot better than they were.

They are not. They are worse, and like to get worse still. Some things, indeed, are wonderfully better: the new miracles of surgery (which have kept me alive who would otherwise have handed in my dinner-pail), public attitudes to the disabled, the health and wellbeing of children (how wonderful they look), intelligent concern for the environment (hideous word, but necessary), the massive strides in science and technology (though I hate to think what Thomas Carlyle would have made of the internet and the mobile phone). Yes, there are material blessings and benefits innumerable which were unknown in our youth.

But much has deteriorated. To one of my generation, who remembers pre-war, war-time, and post-war (as most of the present population and their governors do not) and who has travelled widely and now lives, in a real sense, overseas, the United Kingdom begins to look more and more like a Third World country, shabby, littered, ugly, running down, without purpose or direction, misruled by a typical Third World government, corrupt, incompetent and undemocratic. My generation has seen the decay of ordinary morality, standards of decency, sportsmanship, politeness, respect for the law, the law itself, family values, politics and education and religion, the very character of the British – oh, how blimpish this must sound to modern ears, how out of date, how blind to the “need for change” in the new millennium!

Well, perhaps it is. We elderly pessimists may be wrong. God knows, if we had a pound for every mistake we’ve made, you could keep the pension. But, if we are old, we are experienced, we have been about, and seen things, and perhaps learned lessons that our juniors do not know … yet. In comparing past and present we have an advantage denied the young: we were there then, and we are here now.

Certainly we tend to be resistant to change, on the whole, but that is because we have learned the hard way that change for its own sake is not a good idea,* and that if something works more or less satisfactorily, it is best not to alter it without long and careful thought. Above all, we have learned Cromwell’s wisdom:

“In the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken.”

Oh, we were young once, and just as cocksure and clueless as younger people today – but we were luckier then than they are now because the means of self-destruction in our time were much more limited, and we laboured under fewer disadvantages.

It follows that I am sorry for the present generation, with their permissive society, their anything-goes philosophy, and their generally laid-back, in-yer-face attitude (sorry, attichood). They regard themselves as a completely liberated society, when the fact is that they are less free than any generation before them since the Middle Ages. Indeed, there may never have been such an enslaved generation, in thrall to hang-ups, taboos, restrictions, and oppressions unknown to their ancestors. (To say nothing of being neck-deep in debt, thanks to a money-lenders’ economy.)

They won’t believe, of course, that they don’t know what freedom is, and that we were freer by far fifty years ago – yes, with conscription, censorship, direction of labour, rationing, and shortages of practically everything that nowadays is regarded as essential to enjoyment, we still had a liberty beyond modern understanding. How so? Because we had other freedoms, the really important ones, that are denied the youth of today.

We could say what we liked; they can’t. We were not subject to the aggressive pressure of special-interest minority groups; they are. We had no worries about race or sexual orientation; they have (boy, do they ever!) We could, and did, differ from fashionable opinion with impunity, and would have laughed political correctness to scorn (had our society been weak and stupid enough to let it exist); they daren’t. We had available to us an education system, public and private, which was the envy of the world; we had little reason to fear being mugged or raped (killed in war, maybe, but that was an acceptable hazard); our children could play in street and country in safety; we had not been brainwashed into displays of bogus grief in the face of tragedy, or into a compensation culture that insists on scapegoats and huge pay-outs for non-existent wrongs; we had few problems with bullies because society knew how to deal with bullying, and was not afraid to punish it in ways which would send today’s progressives into hysterics; we did not know the stifling tyranny of a liberal establishment determined to impose its views, and more and more beginning to resemble Orwell’s Ministry of Truth.

And we didn’t know what an Ecstasy tablet was. God, we were lucky. But above all, perhaps, we knew who we were, and we lived in the knowledge that certain values and standards held true, and that our country, with all its faults and need for reforms, was sound at heart.

Not any more, and we wonder where it went wrong. Speaking from a fairish knowledge of British history and governance, I find it difficult to identify a time when the country was as badly governed as it has been in the last fifty years. I know about Addington and the Cabal and Aberdeen and North but they really look a pretty decent and competent lot when compared with the trash that has infested Westminster since 1945. Of course there have been honourable exceptions; I speak of the generality, and I am almost as disenchanted with Conservative as I am with Labour. Between them they have produced the two worst Prime Ministers in our history (and what bad luck it has been that they have both fallen within the last thirty years). They are, of course, Heath and Blair. The harm that these two have done to Britain is incalculable, and almost certainly irreparable.

Whether the public can be blamed for letting them pursue their ruinous policies is debatable; short of assassination there is little that people can do when their political masters have forgotten the true meaning of the democracy of which they are forever prating, are determined to have their way at all costs, and hold public opinion in contempt.

Does it matter whether today’s and future generations know what the overwhelming majority of their parents and grandparents believed and valued? Probably not; it is a fact of life that after a certain age no one is taken seriously, and an era in which the official wisdom is that history is bunk is not going to pay much heed to a reactionary eccentric like me. But I’ve written it anyway, for the reason that I’ve written all my books: simply because I want to. It’s the best of reasons. Dr Johnson, who said many wise things, could talk tripe with the best of them on occasion, as when he said that no man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money.

What follows is not one long die-hard bellyache, however. It contains some autobiography of one who has been a newspaperman, soldier, encyclopedia salesman (briefly), novelist, and historian, and because, as I said earlier, I know the fascination the film world exerts, my reminiscences of almost thirty years, on and off, as a writer in the movie business. These last will not be sensational or denigratory; I liked, almost without exception, the great ones of the cinema whom I met and worked with, actors, actresses, directors, producers, moguls, and that great legion of technicians, experts, and fixers without whom films wouldn’t get made.

But if I have no exposés, no juicy scandals, it may be that film buffs will still find some interest in Rex Harrison’s enthusiasm for lemonade, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s technique with head-waiters, Federico Fellini’s inability to master his office burglar alarm, Burt Lancaster’s knack of losing car keys (and his possible descent from John of Gaunt), Guy Hamilton’s system for assessing the rough-cut of a picture, Alex Salkind’s consideration of Muhammad Ali for the role of Superman (it’s a fact, I was there), and Oliver Reed’s unique method of crossing the Danube – as well as his thoughts on Steve McQueen, and vice versa.

And other phenomena and personalities. Looking back on Hollywood, Pinewood, Cinecittà, and various other studios and locations from Culver City to the mountaintops of Yugoslavia, I find some of it hard to believe, but I wouldn’t have missed it for anything.

That, then, is the purport of this book, some of which was written as long as twenty-odd years ago, and has been waiting until I had time to finish it and arrange it in some sort of order; it’s fairly random and haphazard, but at least it’s true. It won’t please everyone, I know, but those of ultra-liberal views can console themselves with the thought that my kind won’t be around much longer, and then they can get on with wrecking civilisation in peace; in the meantime (assuming they’ve read this far) they should stick this volume back on the bookshop shelves and turn to recipes about aubergines or shrub cultivation or political memoirs.

For the rest of you, I hope I strike a chord, and that you find the movie stuff as much fun as I did.

* I am taking this opportunity to thank any readers who may be kind enough to write to me about this book, whether in approval or deep damnation, because I doubt if I’ll have the energy to reply to their letters. I’m not being churlish, but life’s too short, honestly, and the postage costs a fortune.

*Just for interest, there is a mistaken belief that the terms Left and Right in politics originated in the French National Assembly during the Revolution. In fact, Edward Gibbon, writing before the Revolution, used the words to indicate the radical and conservative sides in Church politics, as the following quotation from his Decline and Fall makes clear: “The bishops … were attached to the faith of Cyril, but in the face of the synod, in the heat of the battle, the leaders … passed from the right to the left wing, and decided the victory by this seasonable desertion.”

* To quote the wise old judge: “Reform? Reform? Are things not bad enough as they are?”