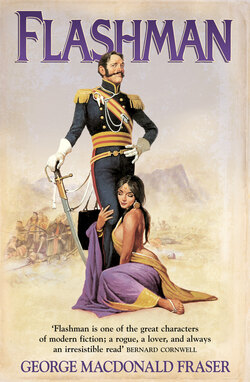

Читать книгу Flashman - George MacDonald Fraser - Страница 14

ОглавлениеI have soldiered in too many countries and known too many peoples to fall into the folly of laying down the law about any of them. I tell you what I have seen, and you may draw your own conclusions. I disliked Scotland and the Scots; the place I found wet and the people rude. They had the fine qualities which bore me – thrift and industry and long-faced holiness, and the young women are mostly great genteel boisterous things who are no doubt bedworthy enough if your taste runs that way. (One acquaintance of mine who had a Scotch clergyman’s daughter described it as like wrestling with a sergeant of dragoons.) The men I found solemn, hostile, and greedy, and they found me insolent, arrogant, and smart.

This for the most part; there were exceptions, as you shall see. The best things I found, however, were the port and the claret, in which the Scotch have a nice taste, although I never took to whisky.

The place I was posted to was Paisley, which is near Glasgow, and when I heard of the posting I as near as a toucher sold out. But I told myself I should be back with the 11th in a few months, and must take my medicine, even if it meant being away from all decent living for a while. My forebodings were realised, and more, but at least life did not turn out to be boring, which was what I had feared most. Very far from it.

At this time there was a great unrest throughout Britain, in the industrial areas, which meant very little to me, and indeed I’ve never troubled to read up the particulars of it. The working people were in a state of agitation, and one heard of riots in the mill towns, and of weavers smashing looms, and Chartists7 being arrested, but we younger fellows paid it no heed. If you were country-bred or lived in London these things were nothing to you, and all I gathered was that the poor folk were mutinous and wanted to do less work for more money, and the factory owners were damned if they’d let them. There may have been more to it than this, but I doubt it, and no one has ever convinced me that it was anything but a war between the two. It always has been, and always will be, as long as one man has what the other has not, and devil take the hindmost.

The devil seemed to be taking the workers, by and large, with government helping him, and we soldiers were the government’s sword. Troops were called out to subdue the agitators, and the Riot Act was read, and here and there would be clashes between the two, and a few killed. I am fairly neutral now, with my money in the bank, but at that time everyone I knew was damning the workers up and down, and saying they should be hung and flogged and transported, and I was all for it, as the Duke would say. You have no notion, today, how high feeling ran; the mill-folk were the enemy then, as though they had been Frenchmen or Afghans. They were to be put down whenever they rose up, and we were to do it.

I was hazy enough, as you see, on the causes of it all, but I saw further than most in some ways, and what I saw was this: it’s one thing leading British soldiers against foreigners, but would they fight their own folk? For most of the troopers of the 11th, for example, were of the class and kind of the working people, and I couldn’t see them fighting their fellows. I said so, but all I was told was that discipline would do the trick. Well, thought I, maybe it will and maybe it won’t, but whoever is going to be caught between a mob on one side and a file of red coats on the other, it isn’t going to be old Flashy.

Paisley had been quiet enough when I was sent there, but the authorities had a suspicious eye on the whole area, which was regarded as being a hotbed of sedition. They were training up the militia, just in case, and this was the task I was given – an officer from a crack cavalry regiment instructing irregular infantry, which is what you might expect. They turned out to be good material, luckily; many of the older ones were Peninsular men, and the sergeant had been in the 42nd Regiment at Waterloo. So there was little enough for me to do at first.

I was billeted on one of the principal mill-owners of the area, a brass-bound old moneybags with a long nose and a hard eye who lived in some style in a house at Renfrew, and who made me welcome after his fashion when I arrived.

‘We’ve no high opeenion o’ the military, sir,’ said he, ‘and could well be doing without ye. But since, thanks to slack government and that damnable Reform nonsense, we’re in this sorry plight, we must bear with having soldiers aboot us. A scandal! D’ye see these wretches at my mill, sir? I would have the half of them in Australia this meenit, if it was left to me! And let the rest feel their bellies pinched for a week or two – we’d hear less of their caterwaulin’ then.’

‘You need have no fear, sir,’ I told him. ‘We shall protect you.’

‘Fear?’ he snorted. ‘I’m not feart, sir. John Morrison doesnae tremble at the whine o’ his ain workers, let me tell you. As for protecting, we’ll see.’ And he gave me a look and a sniff.

I was to live with the family – he could hardly do less, in view of what brought me there – and presently he took me from his study through the gloomy hall of his mansion to the family’s sitting-room. The whole house was hellish gloomy and cold and smelled of must and righteousness, but when he threw open the sitting-room door and ushered me in, I forgot my surroundings.

‘Mr Flashman,’ says he, ‘this is Mistress Morrison and my four daughters.’ He rapped out their names like a roll-call. ‘Agnes, Mary, Elspeth, and Grizel.’

I snapped my heels and bowed with a great flourish – I was in uniform, and the gold-trimmed blue cape and pink pants of the 11th Hussars were already famous, and looked extremely well on me. Four heads inclined in reply, and one nodded – this was Mistress Morrison, a tall, beaknosed female in whom one could detect all the fading beauty of a vulture. I made a hasty inventory of the daughters: Agnes, buxom and darkly handsome – she would do. Mary, buxom and plain – she would not. Grizel, thin and mousy and still a schoolgirl – no. Elspeth was like none of the others. She was beautiful, fair-haired, blue-eyed, and pink-cheeked, and she alone smiled at me with the open, simple smile of the truly stupid. I marked her down at once, and gave all my attention to Mistress Morrison.

It was grim work, I may tell you, for she was a sour tyrant of a woman and looked on me as she looked on all soldiers, Englishmen, and men under fifty years of age – as frivolous, Godless, feckless, and unworthy. In this, it seemed, her husband supported her, and the daughters said not a word to me all evening. I could have damned the lot of them (except Elspeth), but instead I set myself to be pleasant, modest, and even meek where the old woman was concerned, and when we went into dinner – which was served in great state – she had thawed to the extent of a sour smile or two.

Well, I thought, that is something, and I went up in her estimation by saying ‘Amen’ loudly when Morrison said grace, and struck while the iron was hot by asking presently – it was Saturday – what time divine service was next morning. Morrison went so far as to be civil once or twice, after this, but I was still glad to escape at last to my room – dark brown tomb though it was.

You may wonder why I took pains to ingratiate myself with these puritan boors, and the answer is that I have always made a point of being civil to anyone who might ever be of use to me. Also, I had half an eye to Miss Elspeth, and there was no hope there without the mother’s good opinion.

So I attended family prayers with them, and escorted them to church, and listened to Miss Agnes sing in the evening, and helped Miss Grizel with her lessons, and pretended an interest in Mistress Morrison’s conversation – which was spiteful and censorious and limited to the doings of her acquaintances in Paisley – and was entertained by Miss Mary on the subject of her garden flowers, and bore with old Morrison’s droning about the state of trade and the incompetence of government. And among these riotous pleasures of a soldier’s life I talked occasionally with Miss Elspeth, and found her brainless beyond description. But she was undeniably desirable, and for all the piety and fear of hell-fire that had been drummed into her, I thought there was sometimes a wanton look about her eye and lower lip, and after a week I had her as infatuated with me as any young woman could be. It was not so difficult; dashing young cavalrymen with broad shoulders were rare in Paisley, and I was setting myself to charm.

However, there’s many a slip ’twixt the crouch and the leap, as the cavalry used to say, and my difficulty was to get Miss Elspeth in the right place at the right time. I was kept pretty hard at it with the militia during the day, and in the evenings her parents chaperoned her like shadows. It was more for form’s sake than anything else, I think, for they seemed to trust me well enough by this time, but it made things damnably awkward, and I was beginning to itch for her considerably. But eventually it was her father himself who brought matters to a successful conclusion – and changed my whole life, and hers. And it was because he, John Morrison, who had boasted of his fearlessness, turned out to be as timid as a mouse.

It was on a Monday, nine days after I had arrived, that a fracas broke out in one of the mills; a young worker had his arm crushed in one of the machines, and his mates made a great outcry, and a meeting of workmen was held in the streets beyond the mill gates. That was all, but some fool of a magistrate lost his head and demanded that the troops be called ‘to quell the seditious rioters’. I sent his messenger about his business, in the first place because there seemed no danger from the meeting – although there was plenty of fist-shaking and threat-shouting, by all accounts – and in the second because I do not make a practice of seeking sorrow.

Sure enough, the meeting dispersed, but not before the magistrate had spread panic and alarm, ordering the shops to close and windows in the town to be shuttered and God knows what other folly. I told him to his face he was a fool, ordered my sergeant to let the militia go home (but to have them ready on recall), and trotted over to Renfrew.

There Morrison was in a state of despair. He peeped at me round the front door, his face ashen, and demanded:

‘Are they comin’, in Goad’s name?’ and then ‘Why are ye not at the head of your troops, sir? Are we tae be murdered for your neglect?’

I told him, pretty sharp, that there was no danger, but that if there had been, his place was surely at his mill, to keep his rascals in order. He whinnied at me – I’ve seldom seen a man in such fright, and being a true-bred poltroon myself, I speak with authority.

‘My place is here,’ he yelped, ‘defendin’ my hame and bairns!’

‘I thought they were in Glasgow today,’ I said, as I came into the hall.

‘My wee Elspeth’s here,’ said he, groaning. ‘If the mob was tae break in …’

‘Oh, for God’s sake,’ says I, for I was well out of sorts, what with the idiot magistrate and now Morrison, ‘there isn’t a mob. They’ve gone home.’

‘Will they stay hame?’ he bawled. ‘Oh, they hate me, Mr Flashman, damn them a’! What if they were to come here? O, wae’s me – and my poor wee Elspeth!’

Poor wee Elspeth was sitting on the window-seat, admiring her reflection in the panes and perfectly unconcerned. Catching sight of her, I had an excellent thought.

‘If you’re nervous for her, why not send her to Glasgow, too?’ I asked him, very unconcerned.

‘Are ye mad, sir? Alone on the road, a lassie?’

I reassured him: I would escort her safely to her Mama.

‘And leave me here?’ he cried, so I suggested he come as well. But he wouldn’t have that; I realised later he probably had his strongbox in the house.

He hummed and hawed a great deal, but eventually fear for his daughter – which was entirely groundless, as far as mobs were concerned – overcame him, and we were packed off together in the gig, I driving, she humming gaily at the thought of a jaunt, and her devoted parent crying instruction and consternation after us as we rattled off.

‘Tak’ care o’ my poor wee lamb, Mr Flashman,’ he wailed.

‘To be sure I will, sir,’ I replied. And I did.

The banks of the Clyde in those days were very pretty; not like the grimy slums that cover them now. There was a gentle evening haze, I remember, and a warm sun setting on a glorious day, and after a mile or two I suggested we stop and ramble among the thickets by the waterside. Miss Elspeth was eager, so we left the pony grazing and went into a little copse. I suggested we sit down, and Miss Elspeth was eager again – that glorious vacant smile informed me. I believe I murmured a few pleasantries, played with her hair, and then kissed her. Miss Elspeth was more eager still. Then I got to work in earnest, and Miss Elspeth’s eagerness knew no bounds. I had great red claw-marks on my back for a fortnight after.

When we had finished, she lay in the grass, drowsy, like a contented kitten, and after a few pleased sighs she said:

‘Was that what the minister means when he talks of fornication?’

Astonished, I said, yes, it was.

‘Um-hm,’ said she. ‘Why has he such a down on it?’

It seemed to me time to be pressing on towards Glasgow. Ignorant women I have met, and I knew that Miss Elspeth must rank high among them, but I had not supposed until now that she had no earthly idea of elementary human relations. (Yet there were even married women in my time who did not connect their husbands’ antics in bed with the conception of children.) She simply did not understand what had taken place between us. She liked it, certainly, but she had no thought of anything beyond the act – no notion of consequences, or guilt, or the need for secrecy. In her, ignorance and stupidity formed a perfect shield against the world: this, I suppose, is innocence.

It startled me, I can tell you. I had a vision of her remarking happily: ‘Mama, you’ll never guess what Mr Flashman and I have been doing this evening …’ Not that I minded too much, for when all was said I didn’t care a button for the Morrisons’ opinion, and if they could not look after their daughter it was their own fault. But the less trouble the better: for her own sake I hoped she might keep her mouth shut.

I took her back to the gig and helped her in, and I thought what a beautiful fool she was. Oddly enough, I felt a sudden affection for her in that moment, such as I hadn’t felt for any of my other women – even though some of them had been better tumbles than she. It had nothing to do with rolling her in the grass; looking at the gold hair that had fallen loose on her cheek, and seeing the happy smile in her eyes, I felt a great desire to keep her, not only for bed, but to have her near me. I wanted to watch her face, and the way she pushed her hair into place, and the steady, serene look that she turned on me. Hullo, Flashy, I remember thinking; careful, old son. But it stayed with me, that queer empty feeling in my inside, and of all the recollections of my life there isn’t one that is clearer than of that warm evening by the Clyde, with Elspeth smiling at me beneath the trees.

Almost equally distinct, however, but less pleasant, is my memory of Morrison, a few days later, shaking his fist in my face and scarlet with rage as he shouted:

‘Ye damned blackguard! Ye thieving, licentious, raping devil! I’ll have ye hanged for this, as Goad’s my witness! My ain daughter, in my ain hoose! Jesus Lord! Ye come sneaking here, like the damned viper that ye are …’

And much more of the same, until I thought he would have apoplexy. Miss Elspeth had almost lived up to my expectation – only it had not been Mama she had told, but Agnes. The result was the same, of course, and the house was in uproar. The only calm person was Elspeth herself, which was no help. For of course I denied old Morrison’s accusation, but when he dragged her in to confront me with my infamy, as he called it, she said quite matter-of-fact, yes, it had happened by the river on the way to Glasgow. I wondered, was she simple? It is a point on which I have never made up my mind.

At that, I couldn’t deny it any longer. So I took the other course and damned Morrison’s eyes, asking him what did he expect if he left a handsome daughter within a man’s reach? I told him we were not monks in the army, and he fairly screamed with rage and threw an inkstand at me, which fortunately missed. By this time others were on the scene, and his daughters had the vapours – except Elspeth – and Mrs Morrison came at me with such murder in her face that I turned tail and ran for dear life.

I decamped without even having time to collect my effects – which were not sent on to me, by the way – and decided that I had best set up my base in Glasgow. Paisley was likely to be fairly hot, and I resolved to have a word with the local commandant and explain, as between gentlemen, that it might be best if other duties were found for me that would not take me back there. It would be somewhat embarrassing, of course, for he was another of these damned Presbyterians, so I put off seeing him for a day or two. As a result I never called on him at all. Instead I had a caller myself.

He was a stiff-shouldered, brisk-mannered fellow of about fifty; rather dapper in an almost military way, with a brown face and hard grey eyes. He looked as though he might be a sporting sort, but when he came to see me he was all business.

‘Mr Flashman, I believe?’ says he. ‘My name is Abercrombie.’

‘Good luck to you, then,’ says I. ‘I’m not buying anything today, so close the door as you leave.’

He looked at me sharp, head on one side. ‘Good,’ says he. ‘This makes it easier. I had thought you might be a smooth one but I see that you’re what they call a plunger.’

I asked him what the devil he meant.

‘Quite simple,’ says he, taking a seat as cool as you please. ‘We have a mutual acquaintance. Mrs Morrison of Renfrew is my sister. Elspeth Morrison is my niece.’

This was an uneasy piece of news, for I didn’t like the look of him. He was too sure of himself by half. But I gave him a stare and told him he had a damned handsome niece.

‘I’m relieved that you think so,’ said he. ‘I’d be distressed to think that the Hussars were not discriminating.’

He sat looking at me, so I took a turn round the room.

‘The point is,’ he said, ‘that we have to make arrangements for the wedding. You’ll not want to lose time.’

I had picked up a bottle and glass, but I set them down sharp at this. He had taken my breath away.

‘What the hell d’ye mean?’ says I. Then I laughed. ‘You don’t think I’ll marry her, do you? Good God, you must be a lunatic.’

‘And why?’ says he.

‘Because I’m not such a fool,’ I told him. Suddenly I was angry, at this damned little snip, and his tone with me. ‘If every girl who’s ready to play in the hay was to get married, we’d have damned few spinsters left, wouldn’t we? And d’you suppose I’d be pushed into a wedding over a trifle like this?’

‘My niece’s honour.’

‘Your niece’s honour! A mill-owner’s daughter’s honour! Oh, I see the game! You see an excellent chance of a match, eh? A chance to marry your niece to a gentleman? You smell a fortune, do you? Well, let me tell you—’

‘As to the excellence of the match,’ said he, ‘I’d sooner see her marry a Barbary ape. I take it, however, that you decline the honour of my niece’s hand?’

‘Damn your impudence! You take it right. Now, get out!’

‘Excellent,’ says he, very bright-eyed. ‘It’s what I hoped for.’ And he stood up, straightening his coat.

‘What’s that meant to mean, curse you?’

He smiled at me. ‘I’ll send a friend to talk to you. He will arrange matters. I don’t approve of meetings, myself, but I’ll be delighted, in this case, to put either a bullet or a blade into you.’ He clapped his hat on his head. ‘You know, I don’t suppose there has been a duel in Glasgow these fifty years or more. It will cause quite a stir.’

I gaped at the man, but gathered my wits soon enough. ‘Lord,’ says I, with a sneer, ‘you don’t suppose I would fight you?’

‘No?’

‘Gentlemen fight gentlemen,’ I told him, and ran a scornful eye over him. ‘They don’t fight shop-keepers.’

‘Wrong again,’ says he, cheerily. ‘I’m a lawyer.’

‘Then stick to your law. We don’t fight lawyers, either.’

‘Not if you can help it, I imagine. But you’ll be hard put to it to refuse a brother officer, Mr Flashman. You see, although I’ve no more than a militia commission now, I was formerly of the 93rd Foot – you have heard of the Sutherlands, I take it? – and had the honour to hold the rank of captain. I even achieved some little service in the field.’ He was smiling almost benignly now. ‘If you doubt my bona fides may I refer you to my former chief, Colonel Colin Campbell?8 Good day, Mr Flashman.’

He was at the door before I found my voice.

‘To hell with you, and him! I’ll not fight you!’

He turned. ‘Then I’ll enjoy taking a whip to you in the street. I really shall. Your own chief – my Lord Cardigan, isn’t it? – will find that happy reading in The Times, I don’t doubt.’

He had me in a cleft stick, as I saw at once. It would mean professional ruin – and at the hands of a damned provincial infantryman, and a retired one at that. I stood there, overcome with rage and panic, damning the day I ever set eyes on his infernal niece, with my wits working for a way out. I tried another tack.

‘You may not realise who you’re dealing with,’ I told him, and asked if he had not heard of the Bernier affair: it seemed to me that it must be known about, even in the wilds of Glasgow, and I said so.

‘I think I recollect a paragraph,’ says he. ‘Dear me, Mr Flashman, should I be overcome? Should I quail? I’ll just have to hold my pistol steady, won’t I?’

‘Damn you,’ I shouted, ‘wait a moment.’

He stood attentive, watching me.

‘All right, blast you,’ I said. ‘How much do you want?’

‘I thought it might come to that,’ he said. ‘Your kind of rat generally reaches for its purse when cornered. You’re wasting time, Flashman. I’ll take your promise to marry Elspeth – or your life. I’d prefer the latter. But it’s one or the other. Make up your mind.’

And from that I could not budge him. I pleaded and swore and promised any kind of reparation short of marriage; I was almost in tears, but I might as well have tried to move a rock. Marry or die – that was what it amounted to, for I’d no doubt he would be damnably efficient with the barkers. There was nothing for it: in the end I had to give in and say I would marry the girl.

‘You’re sure you wouldn’t rather fight?’ says he, regretfully. ‘A great pity. I fear the conventions are going to burden Elspeth with a rotten man, but there.’ And he passed on to discussion of the wedding arrangements – he had it all pat.

When at last I was rid of him I applied myself to the brandy, and things seemed less bleak. At least I could think of no one I would rather be wedded and bedded with, and if you have money a wife need be no great encumbrance. And presently we should be out of Scotland, so I need not see her damnable family. But it was an infernal nuisance, all the same – what was I to tell my father? I couldn’t for the life of me think how he would take it – he wouldn’t cut me off, but he might be damned uncivil about it.

I didn’t write to him until after the business was over. It took place in the Abbey at Paisley, which was appropriately gloomy, and the sight of the pious long faces of my bride’s relations would have turned your stomach. The Morrisons had begun speaking to me again, and were very civil in public – it was represented as being a sudden love-match, of course, between the dashing hussar and the beautiful provincial, so they had to pretend I was their beau ideal of a son-in-law. But the brute Abercrombie was never far away, to see I came up to scratch, and all in all it was an unpleasant business.

When it was done, and the guests had begun to drink themselves blind, as is the Scottish custom, Elspeth and I were seen off in a carriage by her parents. Old Morrison was crying drunk, and made a disgusting spectacle.

‘My wee lamb!’ he kept snuffling. ‘My bonny wee lamb!’

His wee lamb, I may say, looked entrancing, and no more moved than if she had just been out choosing a pair of gloves, rather than getting a husband – she had taken the whole thing without a murmur, neither happy nor sorry, apparently, which piqued me a little.

Anyway, her father slobbered over her, but when he turned to me he just let out a great hollow groan, and gave place to his wife. At that I whipped up the horses, and away we went.

For the life of me I cannot remember where the honeymoon was spent – at some rented cottage on the coast, I remember, but the name has gone – and it was lively enough. Elspeth knew nothing, but it seemed that the only thing that brought her out of her usual serene lethargy was a man in bed with her. She was a more than willing playmate, and I taught her a few of Josette’s tricks, which she picked up so readily that by the time we came back to Paisley I was worn out.

And there the shock was waiting: it hit me harder, I think, than anything had in my life. When I opened the letter and read it, I couldn’t speak at first; I had to read it again and again before it made sense.

‘Lord Cardigan [it read] has learned of the marriage contracted lately by Mr Flashman of this regiment, and Miss Morrison, of Glasgow. In view of this marriage, his lordship feels that Mr Flashman will not wish to continue to serve with the 11th Hussars (Prince Albert’s), but that he will wish either to resign or to transfer to another regiment.’

That was all. It was signed ‘Jones’ – Cardigan’s toady.

What I said I don’t recall, but it brought Elspeth to my side. She slid her arms round my waist and asked what was the matter.

‘All hell’s the matter,’ I said. ‘I must go to London at once.’

At this she raised a cry of delight, and babbled with excitement about seeing the great sights, and society, and having a place in town, and meeting my father – God help us – and a great deal more drivel. I was too sick to heed her, and she never seemed to notice me as I sat down among the boxes and trunks that had been brought in from the coach to our bedroom. I remember I damned her at one point for a fool and told her to hold her tongue, which silenced her for a minute; but then she started off again, and was debating whether she should have a French maid or an English one.

I was in a furious rage all the way south, and impatient to get to Cardigan. I knew what it was all about – the bloody fool had read of the marriage and decided that Elspeth was not ‘suitable’ for one of his officers. It will sound ridiculous to you, perhaps, but it was so in those days in a regiment like the 11th. Society daughters were all very well, but anything that smacked of trade or the middle classes was anathema to his lofty lordship. Well, I was not going to have his nose turned up at me, as he would find. So I thought, in my youthful folly.

I took Elspeth home first. I had written to my father while we were on honeymoon, and had had a letter back saying: ‘Who is the unfortunate chit, for God’s sake? Does she know what she has got?’ So all was well enough in its way on that front. And when we arrived there who should be the first person we met in the hall but Judy, dressed for riding. She gave me a tongue-in-the-cheek smile as soon as she saw Elspeth – the clever bitch probably guessed what lay behind the marriage – but I got some of my own back by my introduction.

‘Elspeth,’ I said, ‘this is Judy, my father’s tart.’

That brought the colour into her face, and I left them to get acquainted while I looked for the guv’nor. He was out, as usual, so I went straight off in search of Cardigan, and found him at his town house. At first he wouldn’t see me, when I sent up my card, but I pushed his footman out of the way and went up anyway.

It should have been a stormy interview, with high words flying, but it wasn’t. Just the sight of him, in his morning coat, looking as though he had just been inspecting God on parade, took the wind out of me. When he had demanded to know, in his coldest way, why I intruded on him, I stuttered out my question: why was he sending me out of the regiment?

‘Because of your marriage, Fwashman,’ says he. ‘You must have known very well what the consequences would be. It is quite unacceptable, you know. The lady, I have no doubt, is an excellent young woman, but she is – nobody. In these circumstances your resignation is imperative.’

‘But she is respectable, my lord,’ I said. ‘I assure you she is from an excellent family; her father—’

‘Owns a factory,’ he cut in. ‘Haw-haw. It will not do. My dear sir, did you not think of your position? Of the wegiment? Could I answer, sir, if I were asked: “And who is Mr Fwashman’s wife?” “Oh, her father is a Gwasgow weaver, don’t you know?”

‘But it will ruin me!’ I could have wept at the pure, blockheaded snobbery of the man. ‘Where can I go? What regiment will take me if I’m kicked out of the 11th?’

‘You are not being kicked out, Fwashman,’ he said, and was being positively kindly. ‘You are wesigning. A very different thing. Haw-haw. You are twansferring. There is no difficulty. I wike you, Fwashman; indeed, I had hopes of you, but you have destwoyed them with your foolishness. Indeed, I should be extwemely angwy. But I shall help in your awwangements: I have infwuence at the Horse Guards, you know.’

‘Where am I to go?’ I demanded miserably.

‘I have given thought to it, let me tell you. It would be impwoper to twansfer to another wegiment at home; it will be best if you go overseas, I think. To India. Yes—’

‘India?’ I stared at him in horror.

‘Yes, indeed. There are caweers to be made there, don’t you know? A few years’ service there, and the matter of your wesigning fwom my wegiment will be forgotten. You can come home and be gazetted to some other command.’

He was so bland, so sure, that there was nothing to say. I knew what he thought of me now: I had shown myself in his eyes no better than the Indian officers whom he despised. Oh, he was being kind enough, in his way; there were ‘caweers’ in India, all right, for the soldier who could get nothing better – and who survived the fevers and the heat and the plague and the hostile natives. At that moment I was at my lowest; the pale, haughty face and the soft voice seemed to fade away before me; all I was conscious of was a sullen anger, and a deep resolve that wherever I went, it would not be India – not for a thousand Cardigans.

‘So you won’t, hey?’ said my father, when I told him.

‘I’m damned if I do,’ I said.

‘You’re damned if you don’t,’ chuckled he, very amused. ‘What else will you do, d’you suppose?’

‘Sell out,’ says I.

‘Not a bit of it,’ says he. ‘I’ve bought your colours, and by God, you’ll wear ’em.’

‘You can’t make me.’

‘True enough. But the day you hand them back, on that day the devil a penny you’ll get out of me. How will you live, eh? And with a wife to support, bigad? No, no, Harry, you’ve called the tune, and you can pay the piper.’

‘You mean I’m to go?’

‘Of course you’ll go. Look you, my son, and possibly my heir, I’ll tell you how it is. You’re a wastrel and a bad lot – oh, I daresay it’s my fault, among others, but that’s by the way. My father was a bad lot, too, but I grew up some kind of man. You might, too, for all I know. But I’m certain sure you won’t do it here. You might do it by reaping the consequences of your own lunacy – and that means India. D’you follow me?’

‘But Elspeth,’ I said. ‘You know it’s no country for a woman.’

‘Then don’t take her. Not for the first year, in any event, until you’ve settled down a bit. Nice chit, she is. And don’t make piteous eyes at me, sir; you can do without her a while – by all accounts there are women in India, and you can be as beastly as you please.’

‘It’s not fair!’ I shouted.

‘Not fair! Well, well, this is one lesson you’re learning. Nothing’s fair, you young fool. And don’t blubber about not wanting to go and leave her – she’ll be safe enough here.’

‘With you and Judy, I suppose?’

‘With me and Judy,’ says he, very softly. ‘And I’m not sure that the company of a rake and a harlot won’t be better for her than yours.’

That was how I came to leave for India; how the foundation was laid of a splendid military career. I felt myself damnably ill-used, and if I had had the courage I would have told my father to go to the devil. But he had me, and he knew it. Even if it hadn’t been for the money part of it, I couldn’t have stood up to him, as I hadn’t been able to stand up to Cardigan. I hated them both, then. I came to think better of Cardigan, later, for in his arrogant, pigheaded, snobbish way he was trying to be decent to me, but my father I never forgave. He was playing the swine, and he knew it, and found it amusing at my expense. But what really poisoned me against him was that he didn’t believe I cared a button for Elspeth.