Читать книгу Recently Discovered Letters of George Santayana - George Santayana - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеDaniel Pinkas

Among the countless challenges facing the truly monumental and still ongoing publication of the critical edition of The Works of George Santayana, none could have been greater than that of gathering, annotating, and contextualizing the more than three thousand letters that Santayana wrote throughout his life to his family, friends, colleagues, publishers and admirers. This collection ranges from 1868 (a letter to his sisters when he was only five) to 1952, the year of his death. The outcome of this stupendous task is housed in the eight books of letters, edited by the late William Holzberger, that constitute Volume 5 of the critical edition, published between 2003 and 2008.

At the outset of his introduction to The Letters of George Santayana, Holzberger provides an answer to the question: «Who was George Santayana?» that can hardly be improved upon as a succinct presentation of the author:

George Santayana (1863-1952) was one of the most learned and cultivated men of his time. Born in Spain and educated in America, he taught philosophy at Harvard University for twenty-two years before returning permanently to Europe at age forty-eight to devote himself exclusively to writing. He knew several languages, including Latin and Greek. Besides his mastery of English, he was at home in Spanish and French (though he modestly down-played his knowledge of those languages). As a young man, Santayana studied Italian in order to read Dante, Cavalcanti, Michelangelo, and other Platonizing poets in their own language; and, in later life, as a result of his long residence in Rome, he acquired facility in speaking Italian. While a student in Germany during 1886-88, Santayana lived with Harvard friends in an English-speaking boardinghouse in Berlin, thereby missing an opportunity to learn to speak German properly. However he could read the original versions of German literary and philosophical works. He also knew the world, having lived for protracted periods in Spain, America, England, France, and Italy. A true cosmopolitan, Santayana nevertheless always regarded himself a Spaniard and kept his Spanish passport current. He possessed many talents and had a multifaceted personality, and each of those facets is reflected vividly in his letters. World famous as a philosopher, he was also a poet, essayist, dramatist, literary critic, autobiographer, and author of a best-selling novel.2

It is hard to overstate the importance and usefulness of The Letters of George Santayana to Santayana scholars, wherever their focus of interest may lie. The more philosophical letters shed light, often in unexpected ways, on Santayana’s fundamental philosophical tenets: his materialism, his naturalism, his theories of essence and truth, his doctrine of animal faith, his ideal of the «life of reason» and his conception of the spiritual life; they are filled with mordant comments on the views of other philosophers, classical and modern. Many letters state his views on religion, science, literature, history, politics and current affairs. Obviously, the letters are full of crucial biographical information, sometimes sprinkled with delightful gossip. For a less specialized audience also, Santayana’s letters can be a wonderful source of information, inspiration and fun. They offer an unforgettable, and most enjoyable, opportunity to hear, so to say live, the unique voice of a supremely smart and wise philosopher who is at the same time, fully, a human being with a very distinctive history and intellectual background. Santayana’s flair for finding the most appropriate word is everywhere on display, from the briefest thank-you note to the most extensive metaphysical discussion.

The publication of the critical edition was preceded by the publication, in 1955, of about 250 letters that Santayana’s friend and secretary, Daniel Cory, had managed to assemble. In order to locate these letters, Cory published advertisements in leading journals and reviews, he visited the main libraries housing Santayana’s manuscript materials and he wrote to people he thought had been his correspondents. As he undertook this task, he was, as he recounts in the foreword, «a prey to certain misgivings». First, the sheer size of the correspondence of someone who had been an established writer for over sixty years would probably turn out to be forbidding. Secondly,

Santayana was such an accomplished artist in so many fields […] that I wondered if in the more spontaneous rôle of correspondent he might fall short of the very high standard he had always set himself. I knew that he had never sent anything to his publisher in an untidy condition, but always dressed for a public appearance. Above all, I did not want his friends or critics or general audience to say of him what has unfortunately been said of other distinguished writers: What a pity his letters were ever published!3

But as he started receiving letters, Cory’s anxieties were mostly assuaged. Admittedly, the volume of correspondence would be enormous, and everything would have to be sorted in order to eliminate «polite» or banal letters. On the other issues, however, there was nothing to worry about. As Cory wrote: «this large collection of letters soon proved a fresh and exciting adventure. They are essential as a revelation of his life and mind, and a further confirmation of his literary power.»4

Although the critical edition of The Letters of George Santayana aimed painstakingly at comprehensiveness (the editors sent letters of inquiry to sixty-three institutions reported as holding Santayana manuscripts, they ran advertisements in leading literary publications and contacted more than fifty individuals who were potential recipients of Santayana’s letters, and as a result were able to add over two thousand more letters to Cory’s initial set of about a thousand) the ideal of absolute completeness was clearly out of reach: not only because, as we know, Santayana himself destroyed his letters to his mother, but because the editors were unable to locate many letters whose existence could be inferred from Santayana’s or his correspondents’ allusions. Thus, at the end of the editorial appendix of the critical edition, there is a «List of Unlocated Letters» comprising almost one hundred entries. It should be noted that these unlocated letters do not include those, recently discovered, which we are pleased to present in this volume.

The editors of the critical edition of the Letters, however, did mention that none of Santayana’s letters to von Westenholz had been located, just as they comment on the relative scarcity of letters (only six) to John Francis Stanley («Frank»), the second Earl Russell, given the significance of this relationship to Santayana5. In retrospect, therefore, the absence of any letters addressed to Charles Loeser and Baron Albert von Westenholz in the critical edition points unequivocally to the possibility that such letters could exist somewhere. These are two persons to whom Santayana devoted several pages in his autobiography, leaving no doubt as to how much they had meant to him. Let us begin with Charles Loeser.

At the beginning of chapter XV («College Friends») of Persons and Places, Santayana recounts his first meeting with Loeser, at Harvard, in a passage that deserves to be quoted in full:

First in time, and very important, was my friendship with Charles Loeser. I came upon him by accident in another man’s room, and he immediately took me into his own, which was next door, to show me his books and pictures. Pictures and books! That strikes the keynote to our companionship. At once I found that he spoke French well, and German presumably better, since if hurt he would swear in German. He had been at a good international school in Switzerland. He at once told me that he was a Jew, a rare and blessed frankness that cleared away a thousand pitfalls and insincerities. What a privilege there is in that distinction and in that misfortune! If the Jews were not worldly it would raise them above the world; but most of them squirm and fawn and wish to pass for ordinary Christians or ordinary atheists. Not so Loeser: he had no ambition to manage things for other people, or to worm himself into fashionable society. His father was the proprietor of a vast «dry-goods store» in Brooklyn, and rich—how rich I never knew, but rich enough and generous enough for his son always to have plenty of money and not to think of a profitable profession. Another blessed simplification, rarely avowed in America. There was a commercial presumption that man is useless unless he makes money, and no vocation, only bad health, could excuse the son of a millionaire for not at least pretending to have an office or a studio. Loeser seemed unaware of this social duty. He showed me the nice books and pictures that he had already collected—the beginnings of that passion for possessing and even stroking objets-d’art that made the most unclouded joy of his life. Here was fresh subject-matter and fresh information for my starved aestheticism—starved sensuously and not supported by much reading: for this was in my Freshman year, before my first return to Europe.6

The question of whether, or to what extent, this paragraph is redolent of antisemitism has been discussed at length by John McCormick in his biography of Santayana7, and I propose to leave it aside8, in order to concentrate on «the keynote» of the Santayana and Loeser connexion: «pictures and books». Indeed, Loeser immediately became for Santayana a mentor in the field of art appreciation, and later showed him Italy, in particular Rome and Venice, and «initiated [him] into Italian ways, present and past», making Santayana’s life in the country where he chose to reside from the 1920s onwards «richer than it would have been otherwise»9. Even in his early college years, Loeser was, in a small way, what he later became on an international scale: a refined and shrewd art collector. Santayana readily admits that «Loeser had a tremendous advance on [him] in these matters, which he maintained through life: he seemed to have seen everything, to have read everything, and to speak every language»10 A comparison with the eminent art critic Bernard Berenson (who was also Jewish but converted twice), whom Santayana later frequented, immediately springs to Santayana’s mind: Berenson enjoyed the same cultural advantages, and soon gained a public reputation through his writings, which Loeser never did. But the comparison is not at all favorable to Berenson: Loeser, says Santayana, had a sincere love for his favorite subject (the Italian Renaissance) while Berenson was content to merely display it.

Wealth was another big advantage that Loeser had over Santayana. During their early university years, when the two friends went to the theater or the opera in Boston, it was Loeser who inevitably paid; and when, later, they traveled together in Italy, Santayana would contribute a fixed (and modest) daily sum to their expenses, leaving Loeser, who spoke the language, to make the arrangements and pay the bills. Loeser untied the purse with as few qualms as Santayana had in accepting this generosity, because «it was simply a question of making possible little plans that pleased us but that were beyond my unaided means.»11

Aside from a common interest in «books and pictures», one of the factors that obviously brought the two young students together was their status as outsiders, due to their religious origins, respectively Catholic and Jewish, in an overwhelmingly Protestant institution. For Santayana, this marginal status was somewhat compensated by his association, through his mother’s first marriage, with one of Boston’s prominent Brahmin families. But not only was Loeser unashamedly Jewish, his father owned a «dry-goods store», two facts that «cut him off, in democratic America, from the ruling society.»12 This seemed strange to Santayana, considering how much more cultivated his friend was than «the leaders of undergraduate fashion or athletics.» 13 A somewhat ambivalent portrait follows this remark about Loeser’s isolation at Harvard:

He was not good-looking, although he had a neat figure, of middle height, and nice hands: but his eyes were dead, his complexion muddy, and his features pinched, although not especially Jewish. On the other hand, he was extremely well-spoken, and there was nothing about him in bad taste.

The ambivalence is reflected in Santayana’s overall judgment on his relationship with Loeser: «To me he was always an agreeable companion, and if our friendship never became intimate, this was due rather to a certain defensive reserve in him than to any withdrawal on my part.»14 Loeser’s «defensive reserve» and the asymmetry it introduced in their relation, is a constant theme in the pages devoted to him in Persons and Places. When he lived in Florence as a rich bachelor, notes Santayana, Loeser seemed also to be oddly friendless, in spite of knowing the whole Anglo-American colony; and Santayana complains that, in the 1920s, when he regularly stayed at Charles Strong’s Villa Le Balze in Fiesole, next to Florence, Loeser, who had a car, never visited him or invited him to his house: «this made me doubt whether Loeser had any affection for me, such as I had for him, and whether it was faute de mieux, as a last resort in too much solitude, that in earlier years he had been so friendly».15 But this melancholic doubt is quickly dismissed by the ever-realist Santayana: «circumstances change, one changes as much as other people, and it would be unreasonable to act or feel in the same way when the circumstances are different.»16 All in all, Santayana’s gratitude to Loeser for having shown him Italy and for his guidance in the visual arts, is unqualified.

After their college years, in the 1890s, Santayana and Loeser met several times in London. Santayana reports that his friend had become «very English, much to [his] taste»17 and that he was both vastly instructed and amused by Loeser’s «expert knowledge of how an English gentleman should dress, eat, talk, and travel.» Yet those meetings didn’t relieve Santayana of «the latent uneasiness [he] felt about [his] friend»: he actually suspected «a touch of madness in [Loeser’s] nature,»18 to such an extent that he wondered whether, when Loeser boasted of having two original works by Michelangelo in his collection, he was not indulging in wishful thinking. But no, the Michelangelos were authentic, and Loeser had got them cheap. He was a truly terrific collector.

It was in 1895, and with Loeser, that Santayana first visited Rome and Venice. Loeser turned out to be quite the ideal cicerone: «His taste was selective. He dwelt on a few things, with much knowledge, and did not confuse or fatigue the mind.»19 The first impressions upon arriving in Rome may have played a role in Santayana’s ultimate choice of residence:

We reached Rome rather late at night. It had been raining, and the wet streets and puddles reflected the lights fantastically. Loeser had a hobby that architecture is best seen and admired at night. He proposed that we should walk to our hotel. […]. We walked by the Quattro Fontane and the Piazza di Spagna – a long walk.20

In the autobiography, Santayana does not tell us in what year he and Loeser undertook a walking tour of the Apennines, from Urbino to San Sepolcro; but one of the newly found letters (June 8th, 1897) allows us to date the trip. As promised, I will not dwell on Santayana’s stereotyping reflections that accompany his account of this excursion (they concern «the modern Jew» and his purported inability to «apprehend pure spirit»21), and I will limit myself to quoting the memorable exchange the two friends had when they reached the top of the pass:

… after deliciously drinking, like beats on all fours, at a brook that ran down by the road, we looked about at the surrounding hill-tops. They were little above our own level, but numerous, and suggested the top of the world. «What are you thinking of?» Loeser asked. I said: «Geography». «I», he retorted, «was thinking of God.

Loeser died in New York, during a visit in 1928, and was buried in the Cimitero degli Allori in Florence, which welcomed the graves of non-Catholics. By then, his collection comprised over 1’000 pieces, mostly works of Italian Medieval and Renaissance art, but also contemporary works, most notably an impressive collection of fifteen Cézanne paintings. Loeser bequeathed his collection of Old Master prints and drawings to Harvard University’s Fogg Museum of art, eight of his Cézannes to the President of the United States, and a selection of thirty works of art and furnishings to the Florence city council, which are housed in the Quartiere del Mezzanino of Palazzo Vecchio (where one can admire Bronzino’s superb portrait of the poetess Laura Battiferri). The Cézannes were initially shown at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, until the Kennedys took notice of the gift and decided to hang a few of them in the White house. In a letter dated May 2 1961, the First Lady wrote the following to Loeser’s granddaughter, Mrs. Philippa Calnan:

Dear Mrs. Calnan:

I hope you will be as pleased as the President and I are that we have arranged to have the superb Cezanne paintings which you and your father so generously presented to the United States Government hung in the Green Room of the White House. We have selected «The Forest» and «House on the Marne» to be brought here first. We plan to exchange the paintings so that eventually all of them will hang for some time at the White House. The ones not at the White House at any particular time will be in the safekeeping of the National Gallery of Art and on exhibition to the public there. All eight paintings will, of course, while at the National Gallery and while here continue to bear the label «Presented to the United States in memory of Charles A. Loeser».

This arrangement is particularly gratifying to me because I have often admired your father’s paintings at the National Gallery of Art. Please let me know if you come to Washington. I would be delighted to show the paintings to you in their places here at the White House.

With best wishes.

Sincerely yours,

Jacqueline Kennedy

Indeed, Philippa Calnan responded to the First Lady’s invitation and visited the White House at the end of June 1961. Photographs taken during that visit can be seen at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum website.22 Today, three of the Cézannes hang in the National Gallery and five in the White House family quarters, but the eight paintings have never been installed together as an ensemble, as the Loeser bequest directed.

Despite these various donations, a substantial part of Loeser’s collection remained in the estate of the family. At some point between the promulgation of Mussolini’s anti-Jewish racial laws (1938) and the German occupation of Italy (1943) Loeser’s widow, the German pianist Olga Lebert Kauffman, their daughter, son-in-law and granddaughter left Florence, leaving behind valuable works of art, and ultimately settling in the United States. Several works from the Loeser collection were on the authoritative list of Nazi-plundered art compiled by the art historian Rodolfo Silviero (aka «the 007 of plundered art»), and at least two have been returned to the family. The Middle and High Schools of the International School of Florence are housed since 2003 in Loeser’s Villa Torri La Gattaia, situated on a hill overlooking Florence.

***

The long early letters (1886-1888) of Santayana to Loeser contain extensive and captivating philosophical passages, while the later (and shorter) ones concern mainly the logistics of the meetings of the two friends in Europe. The last dated letter of the collection (October 26th, 1912) is a beautiful letter of congratulations on the occasion of Loeser’s late marriage to Olga Lebert Kaufmann.

But how did this fine and long-forgotten set of letters come to light again? Like the discovery of penicillin, X-rays or rubber, though admittedly not quite as consequential, locating Santayana ’s letter to Charles Loeser was a matter of serendipity. Following Irving Singer ’s suggestion, who had written that the «Santayana-Cory-Strong triangle»23 (was «almost worthy of Proust or Henry James in its subtlety,» I began searching for Charles A. Strong’s letters to Santayana, so as to gain a fairer appreciation of the (at times acrimonious) philosophical discussions that took place, for decades, between the two old friends. Strong kept Santayana’s letters, which are included in The Letters of George Santayana, but Santayana hardly ever kept any letters addressed to him. Strong, however, took with utmost seriousness his debates with Santayana, so he made copies of some of his letters to his friend.

In the midst of my research, I came across the Archives Directory for the History of Collecting in America, hosted on the Frick Collection website. One of the entries indicated that Houghton Library at Harvard had received in 2012 a box of documents labelled «Letters from William James and George Santayana to Charles Alexander Loeser, 1886-1912 and undated.» The entry also mentioned that it was a donation in memory of Charles A. Loeser made by his granddaughter, Philippa Calnan. Given the importance Santayana granted to his friendship with Loeser in his autobiography and the absence of any letters to this recipient in the critical edition of the Santayana’s letters, I knew right away that I had chanced upon something interesting. The librarian I contacted at Houghton Library informed me that the documents had not yet been scanned, but that they could do so quickly. In September 2018, by an amusing coincidence, I was at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence where I had just visited the rooms dedicated to the Loeser bequest, when I received the compressed files of Santayana’s letters to Loeser.

***

To date, we have not been able to ascertain the precise origin of the second batch of letters published in this book. We only know that in 2016 the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University reported that a collection of 60 letters written between 1903 and 1937 by Santayana to Baron Albert Wilhelm Freiherrn von Westenholz, had been added to their George Santayana Papers archive.

Santayana talks about Westenholz (from here onwards I will drop the «von», following Santayana’s practice) in the first chapter of the second part of Persons and Places, titled «Germany». Between 1886 and 1888, Santayana spent two semesters studying in Berlin. After that he made several holiday visits to Germany, the last of which

[he] called a Goethe pilgrimage, because [he] went expressly to Frankfort and to Weimar to visit the home of Goethe’s childhood and that of his old age.[He] was then preparing [his] lectures on Three Philosophical Poets, of whom Goethe was to be one. Even that, however, would probably not have induced me to revisit Germany had I not meantime formed a real friendship with a young German, Baron Albert von Westenholz.24

The Baron, born in 1879 in Hamburg, was the son of a banker («originally perhaps Jewish») and of the daughter of a Bürgermeister (mayor) of that city («with the most pronounced Hanseatic Lutheran traditions»).25 Westenholz spent his apprenticeship at the London branch of the bank where his father was a partner, and learned to speak English, «perfectly» according to Santayana. However, he was never appointed by the firm, for, as the reader of Santayana’s letters is soon made aware, Westenholz’s mental health «was far from good; he suffered from various forms of mental or half-mental derangement, sleeplessness, and obsessions.»26

Around 1900, Westenholz turned up at Harvard. Santayana recounts the beginnings of their friendship as follows:

I was then, in 1900-1905, living at No. 60 Brattle Street, and had my walls covered with Arundel prints.27 These were the starting-point of our first warm conversations. I saw at once that he was immensely educated and enthusiastic, and at the same time innocence personified; and he found me sufficiently responsive to his ardent views of history, poetry, religion, and politics. He was very respectful, on account of my age and my professorship; and always continued to call me lieber Professor or Professorchen; but he would have made a much better professor than I, being far more assiduous in reading up all sorts of subjects and consulting expert authorities.28

We do not know how long Westenholz stayed at Harvard, nor whether he ever graduated. But after he left Cambridge, Santayana visited him three times in Hamburg, where he met his invalid mother and his older sister Mathilde; the two friends also met in London, Amsterdam and Brussels, but never in Italy, despite Santayana’s numerous attempts to lure Westenholz to a country «where we should have found so many themes for enthusiastic discussion.»29

Santayana considered Westenholz one of the three best educated persons he had known,30 none of whom, as he remarks, had ever gone to school. He can best be described as a Privatgelehrter (private scholar) who wrote and translated poetry (notably Santayana’s sonnets) and, who, like Loeser, was an avid collector.31 The admiration and affection Santayana expresses towards his German friend in Persons and Places are fully corroborated by the newly found letters, amply confirming the statement with which Santayana begins the section dedicated to this relationship: «Westenholz was one of my truest friends. Personal affection and intellectual sympathies were better balanced and fused between him and me than between me and any other person.»32 In passing, they provide a stinging rebuttal to Bertrand Russell’s impression that Santayana was «a cold fish».33 The tone of Santayana’s letters is uniformly affectionate, sometimes confessional, with frequent and delightful humorous touches. Santayana’s concern for the Baron’s mental condition is a recurring theme, which he addresses with profound empathy and admirable tact. The topics range freely from personal, occasionally intimate, matters to extensive and always lively discussions of philosophy, religion, culture, politics and literature. This is one of those cases where one can only regret not having at one’s disposal the letters that make up the other half of the correspondence.

There is no better way, I believe, to get a sense of Westenholz’s torments and personal qualities than to read the last two paragraphs devoted to him in Persons and Places, respectively titled «His obsessions» and «His unclouded intelligence»:

As for him, his impediments were growing upon him. Fear of noise kept him awake, lest some sound should awake him; and he carried great thick curtains in his luggage to hang up on the windows and doors of his hotel bedrooms. At Volksdorf, his country hermitage, the floors were all covered with rubber matting, to deaden the footfalls of possible guests; and he would run down repeatedly, after having gone to bed, to make sure that he had locked the piano: because otherwise a burglar might come in and wake him up by sitting down to play on it! When I suggested that he might get over this absurd idea by simply defying it, and repeating to himself how utterly absurd it was, he admitted that he might succeed in overcoming it; but then he would develop some other obsession instead. It was hopeless: and all his intelligence and all his doctors and psychiatrists were not able to cure him. In his last days, as his friend Reichhardt told me, the great obsession regarded bedding: he would spend half the night arranging and rearranging mattresses, pillows, blankets and sheets, for fear that he might not be able to sleep comfortably. And if ever he forgot this terrible problem, his mind would run over the more real and no less haunting difficulties involved in money-matters. The curse was not that he lacked money, but that he had it, and must give an account of it to the government as well as to God. And there were endless complications; for he was legally a Swiss citizen, and had funds in Switzerland, partly declared and partly secret, on which to pay taxes both in Switzerland and in Germany; and for years he had the burden of the house and park in Hamburg, gradually requisitioned by the city government, until finally he got rid of them, and went to live far north, in Holstein, with thoughts of perhaps migrating to Denmark. A nest of difficulties, a swarm of insoluble problems making life hideous, without counting the gnawing worm of religious uncertainty and scientific confusion.

The marvel was that with all these morbid preoccupations filling his days and nights Westenholz retained to the last his speculative freedom. Everything interested him, he could be just and even enthusiastic about impersonal things. I profited by this survival of clearness in his thought: he rejoiced in my philosophy, even if he could not assimilate it or live by it; but the mere idea of such a synthesis delighted him, and my Realm of Truth in particular aroused his intellectual enthusiasm. In his confusion he saw the possibility of clearness, and as his friend Reichhardt said, he became sympathetically hell begeistert, filled with inspired light.34

At the end of a letter sent from Cortina d’Ampezzo on July 20, 1931, Santayana takes leave of Westenholz thus: «I wish I could communicate to you the calm, physical and moral, which I enjoy; but I can only send you my impotent good wishes.» And eight years later he announces and comments on the death of his friend as follows:

Hans Reichhardt has given me the belated news that my friend Westenholz killed himself on August 5th […]. We live in old-fashioned tragic times. Westenholz was an extraordinarily well-educated and intelligent person, omnivorous and tireless in following every intellectual interest, but hopelessly neurasthenic and psychopathic all his life, which had become of late a protracted nightmare. At my age the death of friends makes little impression; we are socially all dead long since, for every important purpose; but closing a life is (as Heidegger teaches) rounding it out, given (sic) it wholeness, and in one sense brings the entire figure of a friend more squarely before one than his life ever did when it was still subject to variations.35

Introducción

Daniel Pinkas 36

Entre los incontables retos que afronta la edición crítica de la Obras de George Santayana, verdaderamente monumental y aún en marcha, ninguno podía ser mayor que el de reunir, anotar y contextualizar las más de tres mil cartas que Santayana escribió a lo largo de su vida a su familia, amigos, colegas, editores y admiradores. La colección abarca desde 1868 (una carta que Santayana escribió con cinco años a su hermana) hasta 1952, el año de su muerte. El resultado de una labor tan enjundiosa son los ocho libros de cartas editados por William Holzberger (1932-2017), que componen el volumen V de la edición crítica, publicados entre 2003 y 2008.

Holzberger, al comienzo de su Introducción a las Cartas de George Santayana, responde a la pregunta «¿Quién fue George Santayana?» de un modo difícil de mejorar, en tanto que sucinta semblanza del autor:

George Santayana (1863-1952) fue uno de los hombres de su época más sabio y formado. Nacido en España y educado en América, enseñó filosofía en la Universidad de Harvard durante veintidós años antes de retirarse a Europa a la edad de cuarenta y ocho años para dedicarse exclusivamente a escribir. Dominaba varios idiomas, latín y griego entre ellos. Además de su maestría con el inglés, se sentía cómodo con el español y el francés (aunque, por modestia, minimizaba su conocimiento de estos idiomas). En su juventud, Santayana estudió italiano para poder leer en su idioma a Dante, Cavalcanti, Miguel Ángel y a otros poetas platónicos; y, más tarde, por su larga estancia en Roma, adquirió un italiano hablado fluido. Siendo estudiante en Alemania durante 1886-1888, Santayana vivió junto a sus amigos de Harvard en una pensión donde se hablaba inglés en Berlín, con lo que perdió la oportunidad de hablar alemán correctamente. Podía, no obstante, leer en versión original los libros filosóficos y literarios alemanes. Fue además un buen conocedor del mundo, dado que vivió largos periodos en España, América, Inglaterra, Francia e Italia. Siendo un verdadero cosmopolita, Santayana se consideró siempre no obstante español y renovó su pasaporte español. Muchos eran sus talentos y multifacética su personalidad, aspectos ambos que se reflejan vívidamente en sus cartas. Famoso mundialmente como filósofo, fue también poeta, ensayista, dramaturgo, crítico literario, autor de una autobiografía y de una novela de gran tirada.37

Resulta difícil sobreestimar la importancia y la utilidad de las Cartas de George Santayana para los expertos en Santayana, sea cual sea su objeto de estudio. Las cartas más filosóficas arrojan luz, a menudo de modo imprevisto, sobre las tesis filosóficas fundamentales de Santayana: su materialismo, su naturalismo, sus teorías sobre la esencia y la verdad, su doctrina de la fe animal, su ideal de la «vida de la razón» y su concepción de la vida espiritual; las cartas rebosan comentarios mordaces sobre las opiniones de los demás filósofos, tanto clásicos como modernos. Muchas de ellas establecen sus opiniones sobre religión, ciencia, literatura, historia, política o temas de actualidad Obviamente, las cartas abundan en información biográfica crucial, a veces rociada con deliciosos cotilleos. También para lectores menos especializados, las cartas de Santayana son una asombrosa fuente de información, inspiración y humor. Ofrecen la inolvidable, y muy agradable, oportunidad de oír, digamos en vivo, la voz única de un filósofo sabio e inteligente sobremanera que, a la vez, es un ser humano con una trayectoria y una formación intelectual características. A cada paso se aprecia su habilidad para encontrar la palabra justa, desde la más breve nota de agradecimiento hasta la discusión metafísica más profunda.

La publicación de la edición crítica estuvo precedida por la publicación, en 1955, de casi 250 cartas que Daniel Cory, secretario y amigo de Santayana, consiguió reunir. Para localizar esas cartas, Cory publicó anuncios en periódicos y revistas importantes, acudió a las bibliotecas donde están los manuscritos de Santayana y escribió a quienes él pensaba que se habían carteado con él. Al comienzo de su tarea, como recuerda en el Prólogo, él se encontraba «sujeto a ciertos recelos». El primero, que el tremendo número de remitentes de alguien que había sido un escritor activo durante sesenta años llegara a ser inabordable. El segundo, que

Santayana fue un artista consumado en tantos campos […] que me preguntaba si, escribiendo cartas, algo más espontáneo, podía no alcanzar el elevado nivel que le era siempre característico. Sabía que él nunca había enviado nada a su editor que estuviera sin corregir, sino que siempre estaba listo para publicar. Sobre todo, yo no quería que sus amigos, críticos o público dijera de él lo que se ha dicho, desafortunadamente, de otros escritores: ¡Qué pena que se han publicado sus cartas!38

Pero, conforme fue recibiendo cartas, se apaciguó la preocupación de Cory. Lo cierto es que la cantidad de correspondencia fue enorme y hubo que recortar, eliminando cartas banales o escritas meramente «por educación». De lo demás, no obstante, no había por qué preocuparse. Como escribió Cory: «enseguida, coleccionar tantas cartas se convirtió en una aventura prometedora e interesante. Son importantes no tanto por lo que revelan de su vida y de sus ideas como por confirmar también su capacidad literaria»39.

La edición crítica de las Cartas de George Santayana aspiró a ser completa y minuciosa (los editores enviaron peticiones a sesenta y tres instituciones que guardaban manuscritos de Santayana, publicaron anuncios en la revistas literarias de referencia y escribieron a más de cincuenta personas que eran, en principio, receptores de cartas de Santayana; fueron así capaces de añadir unas dos mil cartas más al conjunto inicial de las mil que reunió Cory), con todo, el ideal de que la edición fuese realmente completa era claramente inalcanzable; no solo porque, como es sabido, Santayana destruyó sus cartas a su madre sino porque los editores no pudieron localizar muchas cartas cuya existencia se infería de las alusiones de Santayana o de sus corresponsales. De ahí que el apéndice editorial incluya al final una «Lista de cartas sin localizar» con casi cien nombres. Es reseñable que, entre esas cartas sin localizar, no se incluyan las descubiertas recientemente, que son las que damos gustosamente a conocer en este libro.

Los editores de la edición crítica de las Cartas, sin embargo, sí que mencionan que no se había encontrado ninguna de las cartas de Santayana a von Westenholz, precisamente cuando comentan la relativa escasez de cartas (solamente seis) a John Francis Stanley («Frank»), el segundo conde Russell, dada la relevancia de esa relación para Santayana40. Visto retrospectivamente, que no hubiera en la edición crítica cartas dirigidas a Charles Loeser ni al barón Albert von Westenholz señalaba inequívocamente la posibilidad de que esas cartas estuvieran en algún sitio. Santayana dedicó varias páginas de su autobiografía a ambos, donde quedaba claro que eran muy importantes para él. Comencemos por Charles Loeser.

Al comienzo del capítulo XV («Amigos de la universidad») de Personas y lugares, Santayana recuerda su primer encuentro con Loeser, en Harvard, en un pasaje que merece ser citado completo:

La primera en el tiempo, y muy importante, fue mi amistad con Charles Loeser. Lo conocí por casualidad en la habitación de otro e inmediatamente me llevó a la suya que estaba al lado a enseñarme sus libros y sus cuadros. ¡Cuadros y libros! Eso marca la clave de nuestro compañerismo. Enseguida descubrí que hablaba francés bien y alemán probablemente mejor, puesto que cuando se hacía daño soltaba palabrotas en alemán. Había estado en un buen colegio internacional en Suiza. Enseguida me dijo que era judío, rara y bendita franqueza que despejó mil escollos y fingimientos. ¡Qué privilegio el de esa distinción y esa desventura! Si los judíos no fueran mundanos los elevaría por encima del mundo; pero la mayoría se revuelve y lisonjea y prefiere pasar por cristianos corrientes o por ateos corrientes. No así Loeser. Él no tenía ambición por administrar las cosas de otros, ni de introducirse en la sociedad elegante. Su padre era propietario de una gran «mercería» en Brooklyn y rico —nunca supe lo rico que era, pero lo bastante rico y generoso para que su hijo siempre tuviera dinero en abundancia y no tuviera que pensar en una profesión lucrativa—. Otra bendita simplificación raramente conocida en América. Existía una presunción comercial de que un hombre no vale a menos que haga dinero y ninguna vocación, solamente la mala salud, podía servir de excusa al hijo de un millonario para no pretender, al menos, tener un despacho o un estudio. Loeser parecía ajeno a este deber social. Me enseñó los estupendos libros y cuadros que ya había coleccionado — los comienzos de esa pasión de poseer e incluso acariciar objects d’art— que constituyó el gozo más claro de su vida. Ahí tenía yo materia e información frescas para mi hambriento esteticismo — hambriento sensorialmente y no respaldado por muchas lecturas, puesto que era mi primer año universitario, antes de mi primer regreso a Europa.41

La cuestión de si, y hasta qué punto, este párrafo rezuma antisemitismo fue ampliamente discutido por John McCormick en su biografía de Santayana42, así que yo la dejaré a un lado43, para centrarme en la «clave» de la relación de Santayana con Loeser: «cuadros y libros». En realidad, Loeser se convirtió enseguida en referente para Santayana en el ámbito de la apreciación artística y, más tarde, le enseñó Italia, especialmente Roma y Venecia, donde lo «inició en la costumbres italianas, presentes y pasadas», facilitando la vida de Santayana en el país que él acabó eligiendo como residencia a partir de los años veinte, «de un modo más pleno que en ningún otro lugar»44. Ya en sus años de estudiante joven, Loeser era, a pequeña escala, lo que luego llegó a ser a escala internacional: un coleccionista de arte refinado y perspicaz. Santayana confiesa que «Loeser me llevaba en esas cuestiones una tremenda ventaja que mantuvo toda su vida. Parecía haberlo visto todo, haberlo leído todo y hablar todos los idiomas»45. Enseguida, acude a la mente de Santayana compararlo con el famoso crítico de arte Bernard Berenson (también judío, aunque convertido dos veces), a quien Santayana conoció más tarde. Berenson contaba con el mismo bagaje cultural y enseguida sus escritos le hicieron famoso, algo que Loeser nunca logró. Pero Loeser no sale del todo malparado en la comparación: según Santayana, Loeser amaba sinceramente su tema favorito (el Renacimiento italiano), mientras que a Berenson le bastaba simplemente con lucirlo.

Loeser tenía otra gran ventaja sobre Santayana: el dinero. Durante sus primeros años universitarios, cuando los dos amigos iban al teatro o a la ópera en Italia, Santayana contribuía con una suma diaria fija (y modesta) a los gastos, y dejaba que Loeser, que hablaba italiano, se las arreglara y pagara las cuentas. Loeser borraba la deuda con tan pocos escrúpulos como los que Santayana tenía para aceptar tal generosidad, porque «era simplemente cuestión de hacer posibles planes que nos apetecían pero que no estaban a mi alcance sin ayuda»46.

Además de su común interés en «libros y cuadros», uno de los elementos que, obviamente, reunió a los dos jóvenes estudiantes fue que ambos eran outsiders, dados sus orígenes religiosos, católico y judío respectivamente, en una institución claramente protestante. Para Santayana, esa posición marginal quedó algo equilibrada por su relación, basada en el primer matrimonio de su madre, con una de las familias prominentes de Boston. Pero no es solo que Loeser fuera declaradamente judío, sino que su padre tenía una «mercería», dos hechos que «lo aislaban, en la América democrática, de la sociedad dirigente»47. Algo que a Santayana le parecía extraño dado que su amigo estaba mejor formado que «las figuras del estudiantado o del atletismo»48. Este recuerdo sobre el aislamiento de Loeser en Harvard viene seguido de un retrato algo ambivalente:

No era guapo, aunque esbelto, de estatura mediana y manos agradables; pero sus ojos estaban apagados, su tez cetrina y sus facciones acusadas, aunque no precisamente judías. Por otra parte, hablaba extremadamente bien y no había nada en él de mal gusto.

Esa ambivalencia se refleja en el juicio de Santayana sobre su relación con Loeser: «Para mí, siempre fue un compañero agradable, y si nuestra amistad nunca llegó a ser íntima, más se debió a cierta reserva defensiva por su parte.»49 La «reserva defensiva» de Loeser y la asimetría que se introducía así en su relación es un tema constante en las páginas que le dedica en Personas y lugares. Cuando él vivía en Florencia como un rico bachiller, anota Santayana, parecía también extrañamente sin amigos, a pesar de que sabía que había allí un grupo de anglo-americanos, y Santayana se queja de que, en los años veinte, cuando él se quedaba habitualmente en la Villa Le Balze de Charles Strong en Fiesole, cerca de Florencia, Loeser nunca fue a visitarlo, a pesar de tener coche: «esto me hacía dudar si Loeser habría sentido por mí algún afecto, como el que yo sentí por él, o si no fue más que faute de mieux, como último recurso en la excesiva soledad, el que en los primeros años hubiera mostrado tanta amistad».50 Pero esa duda melancólica se disipaba rápidamente en Santayana, siempre realista: «las circunstancias cambian, uno cambia tanto como los demás y no sería razonable actuar o sentirse de la misma manera cuando las circunstancias son distintas»51. En cualquier caso, la gratitud de Santayana para con Loeser por haberle enseñado Italia y su ayuda en las artes plásticas quedó incólume.

Después de sus años universitarios, en la década final del siglo, Santayana y Loeser se encontraron varias veces en Londres. Santayana cuenta que su amigo se había vuelto «muy inglés, muy de mi gusto»52 y que él quedó tanto instruido como entretenido con el conocimiento de Loeser sobre cómo «debe vestir, comer, hablar y viajar un caballero inglés». Con todo, esos encuentros no le quitaban a Santayana «la latente intranquilidad que sentía por mi amigo»; en realidad él sospechaba de «cierto grado de locura en su carácter»53, hasta tal punto que se pregunta si, cuando Loeser se jactaba de tener dos obras originales de Miguel Ángel en su colección, no estaba tomando sus deseos por la realidad. Pero no, los Miguel Ángel era auténticos, y Loeser los había conseguido baratos. Era un coleccionista realmente magnífico.

Fue en 1895, y con Loeser, cuando Santayana visitó Roma y Venecia por vez primera. Loeser se convirtió en todo un cicerone perfecto: «Su gusto era selectivo. Se explayaba en unas pocas cosas, con gran conocimiento, y no confundía ni fatigaba la mente»54. La primera impresión tras llegar a Roma pudo haber influido en la elección final por parte de Santayana para hacerla su residencia:

Llegamos a Roma bastante tarde por la noche. Había estado lloviendo y las calles mojadas y los charcos reflejaban las luces de manera fantástica. Loeser opinaba que la arquitectura se ve y se admira mejor por la noche. Propuso que fuéramos a pie hasta nuestro hotel. […] Pasamos Quattro Fontane y Piazza di Spagna, un largo trayecto.55

En la autobiografía, Santayana no nos cuenta en qué año Loeser y él hicieron un viaje por los Apeninos, desde Urbino hasta San Sepolcro; pero una de las cartas recientemente encontradas (8 de junio de 1897) nos permite fechar la ruta. Como he prometido, no destacaré las reflexiones estereotipadas de Santayana (sobre «el judío moderno» y su supuesta incapacidad para «aprehender el puro espíritu»56) que acompañan la descripción de su excursión; me limitaré a citar la memorable conversación entre los dos amigos cuando llegaron a la cima del puerto:

… después de beber con delicia, a cuatro patas como las bestias, en un arroyo que bajaba junto a la carretera, contemplamos las cumbres de alrededor. Se elevaban poco por encima de nuestro propio nivel, pero eran numerosas y sugerían la cima del mundo. «¿En qué estás pensando?», me preguntó Loeser. «En la geografía», le dije. «Yo», replicó secamente, «estaba pensando en Dios».

Loeser murió en Nueva York durante una visita en 1928 y fue enterrado en el Cimitero degli Allori en Florencia, que admitía enterrar a no-católicos. Por entonces, su colección comprendía 1.000 piezas, la mayoría de arte medieval y renacentista italiano, aunque también obras contemporáneas, entre las que destacan quince cuadros de Cézanne. Loeser legó su colección de grabados y pinturas de Maestros antiguos al Fogg Museum de la Universidad de Harvard, ocho de sus Cézanne al presidente de Estados Unidos y una selección de treinta obras de arte y mobiliario al Ayuntamiento de Florencia, que los guarda en el Quartiere del Mezzanino del Palazzo Vecchio (donde puede admirarse el soberbio retrato de la poetisa Laura Battiferri). Los Cézanne estuvieron expuestos en la National Gallery of Art de Washington, hasta que los Kennedy se enteraron de la donación y decidieron colgarlos en la Casa blanca. En carta del 2 de mayo de 1961, la Primera dama le escribió a la nieta de Loeser, Mrs. Philippa Calnan:

Estimada Mrs. Calnan:

Confío en que a usted le agrade tanto como al Presidente y a mí que hayamos decidido colgar las soberbias pinturas de Cézanne que usted y su padre entregaron al gobierno de Estados Unidos en la Habitación verde de la Casa blanca. Hemos seleccionado «El bosque» y «Casa a orillas del Marne» para que vengan las primeras. Hemos pensado ir cambiando los cuadros de modo que, al final, todos hayan sido colgados durante algún tiempo en la Casa blanca. Los que no estén en la Casa blanca por un tiempo determinado estarán al cuidado de la National Gallery of Art y se exhibirán al público ahí. Los ocho cuadros, naturalmente, seguirán llevando el rótulo «Entregado a los Estados Unidos en recuerdo de Charles A. Loeser». Este acuerdo me es grato de modo particular porque yo he admirado siempre los cuadros de su padre en la National Gallery of Art. Hágame el favor de hacerme saber si va a venir a Washington; me encantaría mostrarle los cuadros tal y como están aquí, en la Casa blanca.

Con mis mejores deseos.

Sinceramente suya,

Jacqueline Kennedy

Por supuesto que Philippa Calnan respondió a la invitación de la Primera dama y visitó la Casa blanca a finales de junio de 1961. En la Biblioteca presidencial John F. Kennedy y en la página web del Museo pueden verse las fotos que recogieron esa visita57. Hoy en día, tres de los Cézanne cuelgan de la National Gallery y cinco en la zona privada de la Casa blanca, pero nunca se han instalado juntos los ocho cuadros como grupo, tal como estableció el legado de Loeser.

A pesar de esas donaciones, la mayor parte de la colección de Loeser siguió perteneciendo a la familia. En algún momento entre la promulgación de las leyes raciales contra los judíos de Mussolini (1938) y la ocupación alemana de Italia (1943), la viuda de Loeser, la pianista alemana Olga Lebert Kauffman, su hija, su yerno y nieta, al final, se asentaron en Estados Unidos. Algunas obras de la colección de Loeser aparecen en la autorizada lista de arte saqueado por los nazis elaborada por el historiador del arte Rodolfo Silviero (llamado «el James Bond del mundo del arte») de las cuales al menos dos volvieron a la familia. Los grados medio y alto de la International School de Florencia ocupan, desde el año 2003, la Villa Torri La Gattaia de Loeser situada sobre una colina desde la que se divisa Florencia.

***

Las extensas cartas (1886-1888) de Santayana a Loeser incluyen pasajes filosóficos extensos y cautivadores, mientras que las últimas (y más breves) tratan principalmente sobre la logística de los encuentros de los dos amigos en Europa. La última carta de la colección (26 de octubre de 1912) es una bella carta de felicitación con ocasión del tardío matrimonio de Loeser con Olga Lebert Kaufmann.

Pero, ¿cómo han salido a la luz de nuevo este grupo de interesantes cartas tanto tiempo olvidadas? Como el descubrimiento de la penicilina, los rayos X o el caucho, aunque evidentemente sin tanta importancia, localizar las cartas a Charles Loeser fue un ejemplo de serendipia. Siguiendo la sugerencia de Irving Singer, quien escribió que «el triángulo Santayana-Cory-Strong»58 fue «merecedor de Proust o de Henry James por su sutileza», comencé a buscar las cartas de Charles A. Strong a Santayana para lograr una mejor apreciación de las discusiones filosóficas (mordaces, por momentos) que sostuvieron durante décadas los dos viejos amigos. Strong guardó las cartas de Santayana, incluidas en las Cartas de George Santayana, pero Santayana apenas guardó ninguna de las cartas que recibió. Strong, sin embargo, se tomó con la mayor seriedad sus debates con Santayana, de modo que hizo copias de algunas de sus cartas para su amigo.

Metido en esas investigaciones, llegué al directorio de archivos para la historia del coleccionismo en América, alojado en la página web de la Frick Collection. Una de sus entradas señalaba que la Houghton Library de Harvard había recibido en 2012 una caja con documentos etiquetados «Cartas de William James y de George Santayana a Charles Alexander Loeser, 1886-1912, y sin datar». La ficha mencionaba también que era donación en memoria de Charles A. Loeser hecha por su nieta, Philippa Calnan. Dada la importancia concedida por Santayana a su amistad con Loeser en su autobiografía y la ausencia de cartas a ese destinatario en la edición crítica de las cartas de Santayana, me di cuenta enseguida de que había dado con algo interesante. La persona encargada de la biblioteca con la que me puse en contacto me dijo que los documentos aún no estaban escaneados, pero que lo estarían en breve. Era septiembre de 2018, por una curiosa coincidencia, yo estaba en el Palazzo Vecchio de Florencia, donde acababa de visitar las habitaciones dedicadas al legado de Loeser cuando recibí los ficheros con las cartas de Santayana a Loeser.

***

Hasta la fecha, no se puede asegurar el origen exacto del segundo grupo de cartas publicadas en este libro. Sólo se sabe que, en 2016, la Biblioteca de manuscritos y libros singulares de la Universidad de Columbia informó de que una colección de 60 cartas escritas entre 1903 y 1937 por Santayana al barón Albert Wilhelm Freiherrn von Westenholz se había añadido a su archivo George Santayana Papers.

Santayana habla sobre Westenholz (en adelante, suprimiré el «von», siguiendo la costumbre de Santayana) en el capítulo primero de la segunda parte de Personas y lugares, titulado «Alemania». Entre 1886 y 1888, Santayana pasó dos semestres estudiando en Berlín. Después, visitó varias veces Alemania en vacaciones; la última de ellas la llamó

peregrinación goethiana porque fui expresamente a Francfort y a Weimar a visitar el ambiente natural de la infancia y la vejez de Goethe. Estaba preparando entonces mis conferencias sobre Tres poetas filósofos, de los que uno iba a ser Goethe. Sin embargo, ni siquiera eso me hubiera inducido probablemente a visitar de nuevo Alemania si entre tanto no hubiera entablado una verdadera amistad con un joven alemán, el barón Albert von Westenholz59.

El barón, nacido en 1879 en Hamburgo, era hijo de un banquero («tal vez de origen judío») y de la hija de un Bürgermeister (alcalde) de esa ciudad («de tradiciones luteranas hanseáticas muy pronunciadas»)60. Westenholz se formó en la sección londinense del banco donde su padre era socio, de modo que aprendió a hablar inglés «perfectamente», según Santayana. Sin embargo, él nunca consiguió el nombramiento porque, como el lector de las cartas de Santayana pronto percibe, la salud mental de Westenholz «dejaba bastante que desear; padecía de diversos tipos de trastornos mentales o semimentales, de insomnio y de obsesiones»61.

Alrededor de 1900, Westenholz fue a Harvard. Santayana recuerda el comienzo de su amistad así:

Vivía yo entonces, entre 1900 y 1905, en el número 60 de Brattle Street y tenía las paredes cubiertas con grabados de Arundel62. Estos fueron el punto de partida de nuestras primeras y animadas conversaciones. Enseguida noté que era enormemente culto y entusiasta, y a la vez la inocencia personificada. En mí encontró suficiente sensibilidad ante sus apasionados puntos de vista sobre la historia, la poesía, la religión y la política. Era muy respetuoso, dadas mi edad y mi condición de profesor, y siempre siguió llamándome lieber Professor o Professorchen; pero él habría resultado mucho mejor profesor que yo, siendo mucho más asiduo en el repaso de toda clase de materias y en la consulta de autoridades63.

Se desconoce cuánto tiempo estuvo Westenholz en Harvard ni siquiera si logró graduarse. Pero, después de que él se fuera de Cambridge, Santayana lo visitó tres veces en Hamburgo, donde conoció a su madre inválida y a su hermana mayor, Mathilde; ambos amigos se vieron también en Londres, Ámsterdam y Bruselas, pero nunca en Italia, a pesar de los numerosos intentos de Santayana por atraer a Westenholz a un país64.

Santayana consideraba que Westenholz era uno de sus tres amigos mejor formados que había conocido65; y ninguno, como destaca Santayana, había ido nunca a un colegio. El mejor modo de describirlo es como un Privatgelehrter (sabio autodidacta) que escribía y traducía poesía (especialmente los sonetos de Santayana) y que, como Loeser, era un ávido coleccionista66. La admiración y el afecto que Santayana manifiesta quedan completamente corroborados por las cartas recientemente encontradas, que confirman a las claras la sentencia con la que Santayana comienza la sección dedicada a su relación: «Westenholz fue uno de mis amigos más verdaderos. El afecto personal y las simpatías intelectuales estaban más equilibradas y fusionadas entre nosotros que en mi relación con cualquier otra persona»67. Las cartas, por cierto, suponen una clara refutación de la sensación de Bertrand Russell según la cual Santayana era un «frío como un pez »68. El tono de las cartas de Santayana es homogéneamente afectuoso, a veces, de confesión, con frecuentes y deliciosos toques de humor. La preocupación de Santayana con la salud mental del barón es un tema recurrente, que él trata con profunda empatía y tacto admirable. Los temas se mueven libremente entre lo personal, lo íntimo a veces, y profundas discusiones, siempre muy vivas, sobre filosofía, religión, cultura, política y literatura. Este es uno de esos casos en los que es inevitable lamentar no disponer de las cartas que componen la otra mitad de la correspondencia.

No hay mejor modo, creo, de acercarse a los sufrimientos de Westenholz y a su talante personal que leer los dos últimos párrafos dedicados a él en Personas y lugares, titulados respectivamente «Sus obsesiones» y «Su despejada inteligencia»:

En cuanto a él, se le fueron acumulando las dificultades. El temor al ruido no le dejaba dormir por miedo a que alguno le despertara; y en su equipaje llevaba unas gruesas cortinas grandes para colgarlas en las ventanas y en las puertas de sus cuartos de hotel. En Volksdorf, su refugio campestre, los suelos estaban todos cubiertos de alfombra de goma para amortiguar las pisadas de los posibles invitados; y solía bajar corriendo más de una vez, después de estar metido en la cama, para cerciorarse de que había cerrado el piano, ¡porque de lo contrario, podía entrar un ladrón y despertarlo al sentarse a tocarlo! Cuando le sugerí que podría superar esa idea absurda simplemente contraviniéndola y repitiéndose lo absolutamente absurda que era, reconoció que quizá lograra superarla, pero que entonces desarrollaría alguna otra obsesión en su lugar. No tenía remedio, y ni toda su inteligencia ni todos los médicos y psiquiatras fueron capaces de curarlo. En sus últimos días, según me dijo Reichhart, la gran obsesión se refería a la ropa de la cama: se pasaba media noche colocando una y otra vez los colchones, almohadas, mantas y sábanas, por miedo a no poder dormir cómodamente. Y si alguna vez olvidaba ese terrible problema, su mente enseguida giraba hacia las dificultades, más reales y no menos obsesionantes, que tenían que ver con cuestiones de dinero. La maldición no era que le faltara, sino que lo tenía, y debía rendir cuentas de ello ante el gobierno y ante Dios. Y las complicaciones eran infinitas porque él legalmente era ciudadano suizo, y tenía fondos en Suiza, en parte declarados y en parte secretos, sobre los que pagar impuestos tanto en Suiza como en Alemania; y durante años soportó la carga de la casa y el parque de Hamburgo, poco a poco expropiados por el gobierno municipal, hasta que finalmente se deshizo de ellos y se fue a vivir más al norte, a Holstein, pensando quizá en emigrar a Dinamarca. Un cúmulo de dificultades, una multitud de problemas insolubles que hacían horrible la vida, sin contar el roedor gusano de la incertidumbre religiosa y la confusión científica.

El prodigio fue que con todas esas preocupaciones enfermizas ocupando sus días y sus noches retuviera Westenholz hasta el final su libertad especulativa. Todo le interesaba, podía ser justo y hasta entusiasta en las cosas impersonales. Yo me beneficié de esta supervivencia de claridad mental: él se recreaba con mi filosofía, aunque no fuera capaz de asimilarla o vivir de acuerdo a ella; pero la mera idea de semejante síntesis le deleitaba; mi Reino de la verdad en particular suscitó su entusiasmo intelectual. En su confusión, atisbó la posibilidad de claridad y, como dijo su amigo Reichhardt, quedó magnéticamente hell begeistert, lleno de inspirada luz. 69

Al final de una carta enviada desde Cortina d’Ampezzo el 20 de julio de 1931, Santayana se despide de Westenholz así: «Quisiera poder transmitirte la calma, física y moral, de la que disfruto; pero solo puedo enviarte mis impotentes buenos deseos». Y, ocho años más tarde, anuncia su muerte a sus amigos con este comentario:

Hans Reichhardt me ha dado tardía noticia de que mi amigo Westenholz se suicidó el 5 de agosto […]. Vivimos en una época trágica pasada de moda. Westenholz fue una persona inteligente y extraordinariamente bien formada, era omnívoro e incansable tras cualquier interés intelectual, pero toda su vida fue un neurasténico sin remedio y con problemas psicológicos, que se han convertido finalmente en una prolongada pesadilla. A mi edad, la muerte de los amigos no me impresiona mucho, hace tiempo que todos estaban muertos, socialmente, respecto a las cosas importantes; pero cerrar la vida es (como enseña Heidegger) redondearla, completarla; en cierto sentido, coloca la figura entera de un amigo más perfectamente ante uno de lo que su vida estuvo nunca cuando aún estaba sujeta a cambios70.

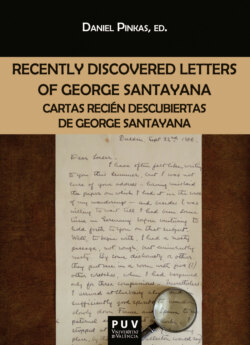

Philippa Calnan junto a Jacqueline Kennedy visitando la Casa Blanca ante Casa a orillas del Marne, de Cezanne / Philippa Calnan with Jacqueline Kennedy visiting the White House posing with Cezanne’s House on the Marne. Autor/Author Robert Knudsen

Bibliografía

Edición crítica de The Works of George Santayana, Cambridge/London: The MIT Press.

1987. W.G. Holzberger and H.J. Saatkamp (eds.). Persons and Places: Fragments of Autobiography.

1988. W.G. Holzberger and H.J. Saatkamp (eds.). The Sense of Beauty. Being the Outlines of Aesthetics Theory.

1990. W.G. Holzberger and H.J. Saatkamp (eds.). Interpretations of Poetry and Religion.

1994. W.G. Holzberger and H.J. Saatkamp (eds.). The Last Puritan. A Memoir in the Form of a Novel.

2001-2008. W.G. Holzberger (ed.). The Letters of George Santayana.

The Letters of George Santayana. Book One (1868-1909), 2001;

The Letters of George Santayana. Book Two (1910-1920), 2001;

The Letters of George Santayana. Book Three (1921-1927), 2002;

The Letters of George Santayana. Book Four (1928-1932), 2003;

The Letters of George Santayana. Book Five (1933-1936), 2003;

The Letters of George Santayana. Book Six (1937-1940), 2004;

The Letters of George Santayana. Book Seven (1941-1947), 2006;

The Letters of George Santayana. Book Eight (1948-1952), 2008.

2011. J. McCormick (ed.). George Santayana’s Marginalia. A Critical Selection, 2 vols.

2011-2016. M.S. Wokeck and M.A. Coleman (eds.). The Life of Reason or The Phases of Human Progress.

I. Introduction and Reason in Common Sense, 2011;

II. Reason in Society, 2013;

III. Reason in Religion, 2014;

IV. Reason in Art, 2015;

V. Reason in Science, 2016.

2019. K. Dawson and D.E. Spiech (eds.) Three Philosophical Poets: Lucretius, Dante and Goethe.

En preparación: Scepticism and Animal Faith y Winds of Doctrine.

Obras recientes de Santayana en castellano por orden de aparición

El sentido de la belleza, trad. de Carmen García Trevijano, Tecnos, Madrid, 2002.

Personas y lugares. Fragmentos de autobiografía, trad. de Pedro García Martín, Trotta, Madrid, 2002.

La vida de la razón, selección de José Beltrán Llavador, Tecnos, Madrid, 2005.

Platonismo y vida espiritual, trad. de Daniel Moreno, Trotta, Madrid, 2006.

Los reinos del ser, trad. de Francisco González Aramburu, FCE, México, 2006.

La filosofía en América, Javier Alcoriza y Antonio Lastra, eds., Biblioteca Nueva, Madrid, 2006.

Fragmentos de correspondencia romana. George Santayana a Robert Lowell, edición trilingüe de Graziella Fantini, Instituto Cervantes de Roma, 2006.

Interpretaciones de poesía y religión, trad. de Carmen García Trevijano y Susana Nuccetelli, Krk, Oviedo, 2008.

La razón en el arte y otros escritos de estética, Ricardo Miguel Alfonso, ed., Verbum, Madrid, 2008.

Tres poetas filósofos: Lucrecio, Dante, Goethe, trad. de José Ferrater Mora, Tecnos, Madrid, 2009.

Soliloquios en Inglaterra y soliloquios posteriores, trad. de Daniel Moreno, Trotta, Madrid, 2009.

Materiales para una utopía. Antología de poemas y dos textos de filosofía, José Beltrán, Manuel Garrido y Daniel Moreno eds., MuVIM, Valencia, 2009.

Dominaciones y potestades, trad. de José Antonio Fontanilla, Krk, Oviedo, 2010.

Escepticismo y fe animal, trad. de Ángel M. Faerna, Antonio Machado Libros, Madrid, 2011.

Ejercicios de autobiografía intelectual, Manuel Ruiz Zamora, ed., Renacimiento, Sevilla, 2011.

El egotismo en la filosofía alemana, edición de Daniel Moreno, Biblioteca Nueva, 2014.

Diálogos en el limbo. Con tres nuevos diálogos, trad. de Carmen García Trevijano y Daniel Moreno, Tecnos, Madrid, 2014.

Pequeños ensayos sobre religión, edición de José Beltrán y Daniel Moreno, Trotta, Madrid, 2015.

Sonetos, traducción de Alberto Zazo, Salto de Página, Madrid, 2016.

La tradición gentil en la filosofía americana, trad. de Pedro García, Krk, Oviedo, 2018.

Ensayos de historia de la filosofía, ed. de Daniel Moreno, Tecnos, Madrid, 2020.

El carácter y la opinión en Estados Unidos, trad. de Fernando García Lida, Krk, Oviedo, 2020.

Ensayos filosóficos, selección y traducción de Daniel Moreno, Prólogo de José Beltrán, Krk, Oviedo, 2021.

Obras recientes sobre Santayana

Alonso Gamo, José María, Un español en el mundo. Santayana, Editorial AACHE, Guadalajara, 20072.

Beltrán, José, Celebrar el mundo. Introducción al pensar nómada de George Santayana, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, 20082.

— Un pensador en el laberinto. Escritos sobre George Santayana, Institució Alfons el Magnànim, Valencia, 2009.

Coleman, Martin, ed., The Essential Santayana. Selected Writings. Indiana University Press, Bloomington & Indianapolis, 2009.

Dossier: Especial George Santayana, Quimera. Revista de literatura, nº 435, 2020, pp. 10-35.

Dossier: George Santayana: la lucidez de la razón, Debats, nº 108/3, 2010, pp. 44-87.

El animal humano. Debate con Jorge Santayana. Edición de Jacobo Muñoz y Francisco J. Martín, Biblioteca Nueva, Madrid, 2008.

Estébanez Estébanez, Cayetano, La obra literaria de George Santayana, Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, 2000.

Fantini, Graziella, Shattered Pictures of Places and Cities in George Santayana’s Autobiography, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, 2009.

Jorge Santayana. Un hombre al margen, un pensamiento central, Archipiélago, nº 70, 2006, 122 pp., número monográfico.

George Santayana at 150. International Interpretations. Edición de M. Flamm, G. Patella y J. Rea, Lexington Books, Nueva York, 2014. [Actas del IV Congreso Internacional sobre Santayana].

George Santayana: un español en el mundo. Edición de Manuel Bermúdez Vázquez, Renacimiento, Sevilla, 2013.

Hodges, Michael y Lachs, John, Pensando entre las ruinas. Wittgenstein y Santayana sobre la contingencia, trad. de Víctor Santamaría, Tecnos, Madrid, 2011.

Kremplewska, Katarzyna, Life as Insinuation. George Santayana’s Hermeneutics of Finite Life and Human Self. State University of New York Press, Nueva York, 2019.

Levinson, Henry, Santayana, Pragmatism, and the Spiritual Life, University of North Carolina Press, Chapell Hill, 1992.

Lida, Raimundo, Belleza, arte y poesía en la estética de Santayana y otros ensayos, edición de Clara E. Lida y Fernando Lida-García, México, El Colegio de México, 2014.

Limbo. Boletín internacional de estudios sobre Santayana, https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/revista?codigo=11264.

La estética de Santayana. Edición de Ricardo Miguel, Verbum, Madrid, 2010.

Los reinos de Santayana, Vicente Cervera y Antonio Lastra, eds., Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, 2002.

Lovely, E. W., George Santayana’s Philosophy of Religion. His Roman Catholic influences and phenomenology, Lanham, MD, Lexington Books, 2012.

McCormick, John, George Santayana. A Biography, Transactions Publishers, New Brunswick, 2003.

Moreno Moreno, Daniel, Santayana filósofo, Trotta, Madrid, 2007.

Overheard in Seville. Bulletin of the Santayana Society, http://indiamond6.ulib.iupui.edu/cdm/search/searchterm/overheard%20in%20seville/field/all/mode/all/conn/and/order/title/ad/asc.

Patella, Giuseppe, Belleza, arte y vida, trad. de Amparo Zacarés, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, 2010.

Pinkas, D. Santayana et l’Amerique de Bon Ton, Metropolis, Ginebra, 2003.

Presencia de Santayana en el cincuentenario de su muerte, Teorema, 2002, nº 1-3, 270 pp., número monográfico, https://dialnet.unirioja.es/ejemplar/102454.

Ruiz Zamora, Manuel, El poeta filósofo y otros ensayos sobre George Santayana, Universidad de Murcia, Murcia, 2014.

Santayana: un pensador universal. Edición de José Beltrán, Manuel Garrido y Sergio Sevilla, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, 2011. [Actas del III Congreso Internacional sobre Santayana].

Saatkamp, Herman J. A Life of Scholarship with Santayana. Editado por Charles Padrón y K. Skowroñski, Brill/Rodopi, 2021.

Savater, Fernando, Acerca de Santayana. Edición de José Beltrán y Daniel Moreno, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, 2011.

Skowroñki, Chris, Santayana and America, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle, 2007.

The Life of Reason in an Age of Terrorism. Edición de Charles Padrón y Krzysztof Pior Skowroñski, Leiden, Boston, Brill-Rodopi, 2018. [Actas del V Congreso Internacional sobre Santayana].

Under Any Sky: Contemporary Readings of George Santayana. Edición de Matt Flamm y Chris Skowroñski, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle, 2007. [Actas del II Congreso Internacional sobre Santayana].

Wahman, Jessica, Narrative Naturalism: An Alternative Framework for the Philosophy of Mind, Lanham, Maryland, Lexington Books, 2015.

A raíz del Tercer Congreso Internacional sobre Santayana celebrado en Valencia en 2009, se creó el blog On George Santayana, donde se dan cuenta de las novedades editoriales y de las actividades en torno a Santayana: http://internationalconferenceonsantayana.blogspot.com/.

A raíz de la pandemia de 2020, Limbo ha aumentado su presencia en las redes con la apertura de una cuenta en Twitter @LimboSantayana, así como en Facebook bajo el «nombre» de Limbo Santayana.