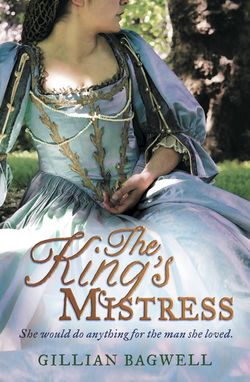

Читать книгу The King’s Mistress - Gillian Bagwell - Страница 10

CHAPTER FOUR

ОглавлениеIT WAS STILL DARK WHEN JOHN KNOCKED ON JANE’S DOOR THE next morning. Her stomach felt shaky with nerves as she washed and dressed, and she tried to shut out Withy’s chatter as she breakfasted. Henry seemed in good spirits, which helped to calm her. He would know what to do if trouble came, and of course the king was a capable soldier. All she really had to do was sit behind the king on a horse, she thought. And keep her head about her.

As the first streaks of pink dawn shot through the grey clouds, John came into the dining room, pulling his coat on.

“It’s time you were off,” he said. “Jane, your horse stands ready.”

When Jane emerged from the house a few minutes later, Withy and her husband and Henry were already mounted, and John and her parents stood waiting to bid them farewell. Jane stared. The young man who held the bridle of her grey mare was unrecognisable from the ragged fugitive of the night before. A bath, a change of clothes, and further cutting of his hair had transformed the king. He was strikingly handsome, his face shaved clean and the mottled brown scrubbed away. His dark hair was now evenly trimmed so that it just brushed his jaw and was combed neatly back. If she had not known the truth, she would have regarded him warily as a Roundhead.

The new suit of clothes in grey wool Jane had provided fit his tall frame admirably. His snapping dark eyes met hers as he pulled off his hat and bowed to her, the very picture of a deferential retainer.

“Good morrow, Mistress. William Jackson, your humble servant.”

“Thank you,” Jane replied, probably too curtly, in an effort to conceal her discomfiture.

The king swung himself into the saddle and offered her his arm—his right arm, the wrong one to enable her to mount easily, and there was a moment of awkwardness as she tried to hoist herself into position. John saw the difficulty and managed a laugh as he came forward to help her.

“The other arm, fellow. You must not be awake yet.”

The king ducked his head in apology and offered his left arm.

“I’m sorry, Mistress,” he said easily. “You’re right, sir, I must still be half dreaming.”

Jane heard her mother give a snort behind her and mutter, “Blockhead.”

John helped Jane settle herself on the pillion behind the king, her feet perched on the little planchette that dangled against the horse’s belly. The king sat astride, facing forward and away from her, but she could not help that her side brushed against his back, and she was intensely aware of his presence. He smelled like soap and wool, and she wondered how long it had been before the previous night that he had bathed or put on clean clothes.

At Jane’s side, John spoke quietly.

“Lord Wilmot and I will follow shortly. We’ll catch up to you and keep within sight of you as long as we may before we branch off towards Packington.”

He gave an almost imperceptible nod to the king, and went to stand beside his wife.

“Travel safely, sister. And Henry.”

Henry touched his hand to his hat in salute, and spurred his strawberry roan gelding into a walk, the dappled mare bearing Withy and her husband following.

“Have a care!” Jane’s mother called as Jane’s grey mare fell in behind the other horses. “Go with God!”

And the journey had begun.

THE SKY WAS PEARLY GREY, AND A LIGHT BLANKET OF MIST LAY OVER the fields that stretched away on either side of the road. The calls of sparrows and wrens echoed in the crisp morning air and a breeze stirred the drifts of brown and golden leaves. The horses’ hooves sounded dully on the muddy road, but Jane was grateful that no rain clouds threatened overhead, and it appeared they would have a fine day for their travels.

Henry spurred his horse to a faster walk, and Withy’s husband, John Petre, followed his lead. As the horses quickened their pace, Jane realised that she had never ridden pillion behind anyone but her father or one of her brothers. She was grasping the little padded handhold of the pillion, but to be really securely seated, she needed to hold on to the king in front of her. What to do? Surely she could not simply slip her arms around the royal person, uninvited? The king seemed to sense her quandary, and turned his head over his shoulder to speak low into Jane’s ear.

“Hold tight to me, Mistress Lane.”

The sudden pressure of his back against her shoulder, the warmth of his breath, and the low rumble of his voice sent a tremor through Jane.

“Yes, Your—yes, I will, thank you.”

She reached around shim with both arms and held fast. Her lower body was facing sideways, but of necessity her right breast was pressed against the king. Dear God, she had never been so close to a man before, she thought, and this sudden physical intimacy jolted her into a new awareness of her own body. Her heart was fluttering in her throat and she swallowed hard, wondering if the king was similarly taking note of the sensation of having her close against him.

The road was mercifully free of many travellers at this early hour, and they passed through Darlaston, Pleck, and Quinton without running into neighbours.

As the sun cleared the horizon, the misty light of dawn gave way to a glorious day. The sky arching overhead was a cloudless blue, and it seemed to Jane that the leaves of the trees, radiant in their autumn golds and reds, stood out more clearly than she had ever noticed before. On either side of the road, the stubble fields and red earth rolled away in gentle waves, broken by the lines of dark stone walls.

“The day could not have been finer had we ordered it,” Jane said to herself.

“Mistress?” The king tilted his head towards her inquiringly.

“Oh! I only remarked how splendid the day.”

“It is indeed. My heart soars with hope, I find.”

He glanced ahead to see if they were overheard, but the thud of the horses’ hooves on the clay of the road covered the sound of their voices. A conversation with the king. Jane’s heart soared, too, and she began to sing softly.

“The east is bright with morning light

And darkness it is fled,

And the merry horn wakes up the morn

To leave his idle bed.”

The king laughed with pleasure. “I’ve not heard that since I was a boy.” He joined in for the chorus, his deep baritone a counterpoint to Jane’s treble.

“The hunt is up, the hunt is up

And it is well nigh day,

And Harry the King is gone hunting

To bring his deer to bay.”

The cheerful mood was catching, and the others sang along as Jane and the king continued with the next verses.

“Behold the skies with golden dyes

Are glowing all around;

The grass is green and so are the treen

All laughing at the sound.”

The cool autumn breeze whispered by them, redolent of hay, livestock, and the deep earthy smell of the fields.

When they had been travelling for only an hour, Henry pointed to two figures off in the distance. John and Lord Wilmot, with hawks on their wrists and John’s hounds tumbling and barking around them as they rode through the open fields.

“Excellent,” the king murmured. “Two good men within sight, should we need them.”

THE PARTY HAD BEEN SOME FOUR HOURS TRAVELLING, AND JOHN and Lord Wilmot had only just disappeared from view, when Jane’s horse cast a shoe.

“What a nuisance,” Withy huffed. “Did not this mooncalf Jackson examine the shoes before we left?”

She glared at the king and he dropped his head to avoid her eyes.

“Bromsgrove lies not far ahead,” Henry said swiftly. “A smith can soon put us to rights, and we’ll not lose much time.”

He glanced at the king, and Jane knew they shared her apprehension about stopping and being seen, but there was no hope of riding as far as Long Marston without the horse being reshod.

As they rode into the little village, they came to an inn posted with the sign of a black cross, and the sound of a blacksmith’s hammer rang out from a small smithy behind it.

“We’ll take the ladies inside for some refreshment, Jackson,” Henry said, helping Jane dismount. He handed the king some coins. “Wet your whistle while you wait for the smith, and fetch me when he’s done.”

“Aye, sir,” the king said.

Withy and John Petre were already entering the inn, but Jane hesitated. Would the king know what to do? Had he even been in a smithy before? He gave her a smile and nodded infinitesimally as he led the grey mare towards the stable yard.

Jane turned to follow the others inside, but her eye was caught by a broadsheet nailed to a post before the inn, its heavy black letters proclaiming “A Reward of a Thousand Pounds Is Offered for the Capture of Charles Stuart”. Glancing around to see if she was observed, Jane edged closer and read with a sinking heart.

“For better discovery of him take notice of him to be a tall man above two yards high, his hair a deep brown, near to black, and has been, as we hear, cut off since the destruction of his army at Worcester, so that it is not very long. Expect him in disguise, and do not let any pass without a due and particular search, and look particularly to the by-creeks and places of embarkation in or belonging to your port.”

Jane moved quickly away from the signpost, desperately wondering what to do. Surely the smith, the grooms and ostlers, all the people of the inn and the town had seen the proclamation, and it must be the same in every village through which they would pass. How could they hope to arrive at Abbots Leigh without the king being discovered?

She had to warn the king, she decided. She walked around to the back of the inn, where the sounds of the blacksmith’s hammer had rung out. The privy was likely to be back there as well, she reasoned, and she could use that as her excuse for skulking in the stable yard should anyone wonder.

As she rounded the corner of the inn, she saw that she was already too late. The smith was examining the grey mare’s shoeless hoof, and the king leaned nonchalantly against a post, watching with apparent interest. He glanced up and smiled when he saw her, seeming completely at ease.

Jane could not think what to do, and needed to relieve herself anyway, so she ducked into the little house of office. No ideas had occurred to her when she emerged a couple of minutes later. A bucket of water and a pannikin of soap stood near the outhouse, and she used the excuse of washing her hands to assure herself that nothing disastrous had happened yet.

So far, all appeared to be well. The king was holding the horse’s hoof while the smith fitted a shoe to it. Shoeing the horse should only take another minute or two. If the smith would only keep his eyes on his work, perhaps they would escape without discovery.

Her heart stopped as the king spoke.

“What news, friend?” Jane was astonished at how naturally he had taken on the accent of a Staffordshire country fellow.

“None that I know of,” the blacksmith answered, reaching for a handful of nails. “Save the good news of the beating of those rogues, the Scots.”

Jane gulped in fear, but the king just nodded.

“Are there none of the English taken that joined with the Scots in the battle?”

“Oh, aye, to be sure,” the smith answered, tapping a nail into place. “But not the one they sought most, that rogue Charles Stuart!”

Jane dropped the soap into the bucket, and the king and the smith glanced her way. She dared not meet the king’s eyes, and busied herself with retrieving the soap.

“You have the right of it, brother,” the king said. “And if that rogue is taken, he deserves to be hanged more than all the rest for bringing in the Scots.”

“You speak like an honest man,” the smith grinned. He squinted at his handiwork, and nodded to the king to let go the horse’s foot. “Well, friend, yon shoe should hold you to wherever you’re bound.”

WHEN THEY WERE SAFELY ON THEIR WAY, JANE WHISPERED URGENTLY to the king about the posted proclamation.

“I would have liked to take to that villainous smith with his own hammer,” she fumed.

“I take his words as no indictment of me,” he shrugged. “The people are weary of war, and want only to go about their lives.”

He began whistling “Jog on the Footpath Way”. Jane wanted to say more, to tell him she was quite sure that most of his subjects passionately shared her desire to have him back on the throne, but mindful of Withy and John Petre, she said nothing. They would be branching off towards their home in Buckinghamshire at Stratford-upon-Avon, which they should reach by midday, and then the journey would be less strained.

The ride continued uneventful for another hour or more, when an old woman working in the field by the side of the road called out, “Don’t you see that troop of cavalry ahead, Master?” She seemed to be addressing the king, rather than Henry or John Petre, and Jane looked at her in alarm. Could she have recognised him? The old woman only nodded slowly, an inscrutable smile on her toothless mouth, and, eyes still on the king, tilted her head at the road before them.

Jane’s eyes followed where the old woman indicated, and to her dismay she saw that about half a mile ahead, a troop of fifty or more men and horses were gathered on both sides of the road. Henry and Withy’s husband slowed their horses and came side by side.

“We must go another way,” John Petre said to Henry.

“They’ve seen us already,” Henry objected. “To turn off now will bring suspicion upon us. I think it safer to continue as though we’ve nothing to fear. And we must cross the river here.”

He started forward, but John Petre grabbed his arm and shook his head obstinately.

“You weren’t beaten by Oliver’s men like I was a while back, for no reason but that they suspected me to be a Royalist. I don’t relish more of the same, and I’ll not take Withy into danger.”

Jane could sense the king’s tension. He leaned back and spoke into her ear.

“Lascelles is right. If we turn back now, it will bring them down upon us. We must go forward.” He clucked to the horse and they pulled abreast of Henry.

“Surely we must ride on,” Jane said to Henry urgently.

Withy turned over her shoulder, shaking her head. “You ride where you’ve a mind to, Jane, but we’ll take a different way.”

“But they see us,” Jane pleaded. “Look.”

They were within a quarter of a mile of the troops now. Men sat or sprawled in the shade of trees, their horses munching at feed bags, and faces were turned towards the approaching riders.

John Petre reined to a halt. “The road we crossed not half a mile back will bring us into Stratford by another way. We’ll take that.”

He doubled back the way they had come.

Henry shook his head in frustration but turned his horse, and there was nothing for it but for the king and Jane to follow. Jane fretted inwardly, but she and Henry had no convincing argument for their urgency, and the king could say nothing.

The road was narrow and led into a wood, but John Petre seemed to know where he was going, and when no sound of pursuing hooves followed them, Jane began to relax again. In half an hour the track curved to the right, passed through a tiny hamlet, and the village of Stratford-upon-Avon lay before them. Soon they would be across the river and free of Withy and John Petre.

“Hell and death,” the king muttered as they rounded a bend.

Jane glanced ahead and felt her stomach drop. The narrow road through the village was thick with horses—the same troop of cavalry they had turned off the road to avoid. Jane’s instinct was to flee, but the soldiers had spotted them, and now there was truly no way but forward without giving the appearance of flight. Henry and the king exchanged the minutest glance and nod, and Henry held back the roan gelding and fell into place behind the grey mare.

The troops were just ahead now, and Jane noted with horror that the broadsheet with the woodcut of the king and announcing the reward for his capture fluttered from a post at the side of the road. Her arms tightened around the king’s waist.

The troopers were turning to look at the approaching party. One officer leaned towards another and they exchanged words, their eyes on the king. Henry took his reins in one hand and the other dropped towards his pistol.

Don’t be a fool, Jane thought. If you draw now, we will all die.

There was some shuffling movement among the mounted men. This is it, Jane thought. We’ve not come even a day’s journey, and already we are lost. An officer raised an arm, glancing around him, and she felt the king stiffen, bracing for an attack.

“Give way there!” the officer cried.

John Petre checked his horse, but the officer’s eyes were on his troops.

“Make way there! Way for the ladies!” he called.

The troopers parted, clearing a narrow lane between them, just wide enough for a single horse to pass through. John Petre and Withy were between them now, and Jane could see that Withy was clutching her husband tightly.

“Good day to you, sir,” John Petre greeted the officer as they passed, his voice strained.

“And you, sir,” the officer replied. Suddenly he frowned, and put up a hand. “Hold, sir, if you please.”

His eyes took in Withy and her husband, Jane and the king, and Henry behind them.

“Where do you travel, sir?”

“Home, sir,” John Petre said. “From a visit to my wife’s family.”

He dug in the pocket of his coat and pulled out the pass for his and Withy’s travel. Jane could see that the back of his coat was dark with sweat. Don’t panic, she willed him, and all will be well.

The officer glanced at the paper and handed it back.

“Very good, sir, travel on.”

His eyes moved to Jane and the king and she held her breath. Perhaps the officer would not trouble himself to check to see that all of them held passes. Her stomach tightened as she recalled that Henry had no pass. She and the king were nearly past the officer now, and he was making no move to stop them. But it could be a trap, she thought. The cavalry could easily close in around her and the king, and it would be futile to fight. She felt the eyes of the men on either side of the road following her.

She forced herself to look into the officer’s face, and gave him a bright smile, trying to still the beating of her heart. He swept his hat from his head and bowed.

“Your servant, Mistress.”

She nodded in reply. The smile froze on her face as the officer’s hand went to the pommel of the saddle.

“Hold, fellow.”

The king reined in the horse. John Petre halted ahead, and Henry of necessity stopped as well. They were surrounded now, their way blocked by the mounted cavalrymen ahead and behind them.

The officer glanced at the king and then at Jane.

“I’m sorry to trouble you, Mistress, but I’m obliged to ask if you have a pass for your travels. These are dangerous times for a lady to be abroad without good reason.”

“I—yes,” Jane stammered. “My—my cousin bears my pass.”

She looked to where Henry sat on the roan. Why, oh, why, had she not carried her pass herself?

Henry rode forward, his face pleasantly bland.

“This is the lady’s pass,” he said, reaching into his pocket. “And here is my own.”

Jane held back a gasp of surprise.

The officer glanced at Jane’s pass and then at her.

“You travel to Abbots Leigh, Mistress?”

“Yes, sir.”

“That’s quite a ways from Staffordshire. What might take you so far?”

Jane strove to keep her voice calm. “I go to see a friend, who is shortly to be brought to bed of her first child.”

She knew her face was flushed, and hoped that the officer might interpret it as embarrassment at having to speak of something so indelicate.

“I see.” His eyes flickered down the paper. “Well. I know the hand to be Colonel Stone’s.”

He glanced at Henry’s pass, and then at Henry.

Please, God, Jane prayed. Please let us go on.

The officer shook his head and spoke to Henry. “Well, I suppose Colonel Stone thought he had good reason, though was she my cousin, I’d not risk her safety on the road just now, even with a manservant along.”

“Your concern is much appreciated,” Henry said smoothly. “But I assure you, I’ll let no harm come to the lady.”

The officer brushed away a fly that threatened to land on his face, and shrugged, apparently satisfied.

“Then I’ll detain you no further. And I bid you good day. Mistress.”

He bowed again as the king clicked to the mare, and now other officers were nodding and bowing to her. She forced a smile as they rode forward. And then they were past the soldiers, and ahead of them lay the sparkling water of the River Avon, and the bridge over it.

NOT FAR ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE RIVER, WITHY AND JOHN PETRE’S way southeast parted from the road towards Long Marston, and they took their leave. Jane, Henry, and the king rode on some way in silence, as though fearing they were not truly alone. It was not until they had continued half a mile or more, the open country stretching away on either side of them, that the king finally laughed out loud in relief, and Henry and Jane joined in.

“I’ve never been so frightened in my life,” Jane cried. “I’m glad we were a-horseback, for sure I would never have been able to stay steady on my feet.”

“Amen to that,” said the king.

“Henry, what on earth did you show him?” Jane asked.

“Why, a pass, cousin,” Henry smiled. “Yours was easy enough to copy, I found.”

The king whistled. “Then were you cool, indeed, sir, while the rogue examined a forged pass. But all’s well that ends well. Now that the danger has passed, I have a great hunger, I find. Would it be agreeable to halt for a rest?”

Their saddlebags were packed with a roasted chicken, bread, cheese, and fruit, and they spread a blanket beneath a tree and ate while the horses grazed. Jane felt the tension leave her. She squinted up at the sun slanting through the golden leaves above and breathed in the sharp autumn air, and the king smiled to see her pleasure.

“Well, despite everything, this feels almost like a holiday. An adventure toward, and a fair companion.”

Jane felt herself blushing, but smiled back, and noted the look of surprise, not altogether happy, on Henry’s face.

IT WAS NEARLY DARK WHEN THEY REACHED LONG MARSTON, A VILLAGE of small thatched cottages, and Jane was relieved that they had no trouble finding the home of her mother’s cousin John Tomes and his family, a substantial half-timbered house near the river. As the king took the horses to the stable, the Tomes family appeared to greet the visitors.

“Cousin Jane! Cousin Henry!” Amy Tomes’s round face shone as she welcomed them into the warm parlour. “It’s a weight off my mind to have you safely here. I wondered if you might choose not to travel, what with the grim news from Worcester.”

“Any trouble on the road?” John Tomes’s expression was grave.

“No,” Henry replied. “Plenty of soldiers, but they let us be. And of course we had Jane’s man Jackson with us.”

“A likely-looking lad!” Amy’s blue eyes twinkled at Jane. “He’s just come into the kitchen, and the cook and the maid are already elbowing each other out of the way to stand next to him. I think we’ll bed him down in the stable, away from the field of battle!”

She laughed merrily and Jane felt a twinge of unease. She had reckoned on staving off Roundhead soldiers, not round-heeled kitchen wenches. But at least her cousins accepted the king as her servant without a second thought.

Upon hearing that Richard Lane had been arrested after the battle, John Tomes produced a printed list of prisoners of war.

“It only names officers,” he said. “But perhaps you’d like to see it.”

Jane read over the names—seven pages, closely printed—from Robert, Earl of Carnworth, down through colonels, majors, captains, lieutenants, cornets, and ensigns, and finally “a list of the king’s domestic servants”, including his apothecary, surgeons, and secretaries. Next to many of the names was the notation “wounded”, or “wounded very much”. She shivered, thinking of Richard.

“Richard’s probably well,” John Tomes comforted her. “If they’ve got organised to print a list of the officers, no doubt more news will come soon.”

“Look at this, if you want something of a lighter cast,” Amy urged.

Jane struggled to maintain a neutral expression as she read the heading on the broadsheet, “A Mad Design or Description of the King of Scots Marching in His Disguise.”

“Silly, isn’t it?” Amy asked. “I pray it may be otherwise, but I fear His Majesty must surely have been slain at Worcester, or we’d have heard of his being taken.”

AFTER SUPPER, JANE WENT UPSTAIRS TO THE SMALL ROOM THAT AMY had made ready for her. It was cosy, a fire dancing in the fireplace, and the soft feather bed and plump pillows called to her. But weary and aching though she was, she longed to see the king before she slept. From the window she could see the stable, and the soft light of a lantern shone from it.

It is my duty to see that he is well bestowed, she thought, that he has all he needs, for he can scarce ask for anything himself. But she knew it was more than that. She wanted to feel the warmth of that smile, the bright light of pleasure and appreciation in his eyes when he looked on her, to hear his laugh.

The house was quiet. Henry was in a room at the other end of the hall, and would not hear her if she crept out. And why should she care if he did know? There was nothing wrong in making sure that her sovereign would spend a comfortable night. But she felt secretive, and was glad that all was dark and still as she opened her bedroom door and slipped down the stairs and out into the yard.

The door of the stable was shut and Jane stood for a moment uncertainly before she gathered her courage to knock. The door swung open in a moment, and the king stood there in breeches and shirt, a blanket wrapped around his shoulders.

“Mistress Lane!” He was surprised to see her, she could see, and she felt foolish.

“The night is cold.” She spoke quietly and then dropped her voice to a whisper. “Your Majesty. Is there anything you lack? Were you well fed?”

“It is cold. Pray come in where it is warmer.”

He held the door open for her and she stepped past him. In the golden glow of the lantern she saw that another blanket lay in a nest of straw, and the warmth from the horses made the place comfortable. The grey mare snorted softly to see her, and the king chuckled.

“I’m not the only one pleased to have a visit, I find.”

He grinned down at Jane. She was suddenly intensely aware of the animal warmth of him, his bare skin glowing in the lantern light where his shirtfront fell open on his chest.

“I have clean clothes, shoes that do not torture my feet, a warm place to sleep, and a belly full of good food. I lack nothing but the pleasure of your company for a few minutes. Come, sit with me.”

He gestured to a bale of straw in as courtly a manner as if he were inviting her to sit upon a silken cushion. Jane sat and he dropped into his nest in the straw and smiled.

“Thanks to you, my spirits tonight are higher than at any time during this last hellish week. Perhaps since I left Jersey more than a year and a half ago.”

“But all that time you were in Scotland. Proclaimed king, and with an army at your back.”

The king snorted in disgust. “Proclaimed king, yes, but kept like a prisoner. The only way the Scots would help me was if I agreed to swear to their Covenant, not only for myself but for all Englishmen, which was much against my conscience to do. And they kept me at my prayers from morning till night, and I swear to you that I exaggerate not one jot. Into my very bedchamber they followed me, hounding me with my wickedness. Truly, I thought I must repent me of ever being born.”

“A foul way to treat one’s king,” Jane said.

He shrugged. “I minded it not so much on my own behalf, but they would have me admit the wickedness of my poor martyred father, and that was beyond enduring. But the worst of it was that I was so alone.”

He looked at her as intently as an artist might his subject, and Jane blushed.

“Alone? Surely not.”

“I assure you, yes. For the Scots deemed my dearest friends more wicked than I, even, and would not countenance their presence. I have been a great while without congenial company. To say nothing of the fact that I have scarce looked on a female face or form in more than a year.”

The air between them seemed to quiver. Jane knew she should go, that somehow she had got into dangerous waters, but she could not make herself move. The king stood and came to her and pulled her gently to her feet, and she went to him as if in a dream. She shivered to feel him so near, his desire palpable, and she felt she could hardly breathe as he put his arm, her hand still in his, behind her, and drew her to him. She looked up at him, his dark eyes shining in the flickering light of the lantern, and it seemed the most natural thing in the world when his lips met hers, feeding delicately upon her. Her free hand reached around his neck and she pulled him closer, feeling the roughness of his close-cropped head in her palm. She smelled his scent and the faint musk of horses, mingled with the wood smoke from the fire and the heavy aroma of the tallow candle.

The kiss seemed to last forever but at last the king straightened and looked down at Jane, his hand stroking her cheek.

“I’m sorry, sweet Jane,” he murmured, kissing her hand. “I shouldn’t have, but I was quite overcome. You’d best go now.”

Jane didn’t want to part from him, but knew that he was right. Reluctantly, she stepped back towards the door.

“Good night. May good rest attend Your Majesty.”

“Charles,” he whispered. “When we are alone so, call me Charles.”

IN HER BED, JANE TOSSED FITFULLY, FEELING CHARLES’S HANDS AND mouth on her, recalling his taste and scent and the feel of his body against hers. She longed for him with every particle of her being, wished that he would creep to her bed in the quiet dark, and was quite appalled at the fierceness of her desire and her complete lack of care for any consequences that might follow should things go further between them. Between her and the king.

JANE’S FIRST SIGHT OF CHARLES IN THE MORNING WAS AT THE BREAKFAST table. He came in from the kitchen with a large pitcher, and he caught her eye and smiled as he went to Henry’s side.

“Cider, sir?” he asked.

“Thank you, Jackson, yes,” Henry said.

“Good morning, Mistress.”

Charles’s sleeve brushed Jane’s arm as he reached for her mug, and she felt herself flushing at the sound of his voice and feel of him so close. She kept her eyes on her plate as he poured for her, but felt that Henry had given her a quick and curious glance.

They set off soon after breakfast, with their noon meal packed in the saddlebags so that they could keep from inns and public eating houses until they reached Cirencester that night.

It was a spectacular day, the air crisp and fresh. With Henry riding ahead of them, whistling happily, Charles reached down and pulled Jane’s hand to his lips and kissed it. She tightened her arms around his waist and felt her heart soar. The sky rose in a vast blue arc above them, before them lay a landscape tinged with rosy sunlight, and all things seemed possible.

They soon left the village behind, and rode on between stubbled fields. The beautiful half-timbered houses of Mickleton gave way to meadowland, and then to substantial houses of pale stone as they reached Chipping Campden, its vaulted stone market stall packed with sheep, and a crowd of traders around the market cross. Leaving the town, the road sloped downward to an open valley.

“Beautiful country,” Charles said. “I haven’t been just here before.”

Jane longed to ask him a thousand questions, about his life, his family, his hopes and plans for what he would do once safely out of England, but didn’t want to seem too inquisitive.

“You have seen much of the country, have you not?”

“Yes, some. During the war, of course. And before the war, for most of the year my family moved between Whitehall, Hampton Court, Windsor, and the other palaces not far from London. But during the summers the king my father and my mother would go on progress throughout the country, staying in turn at other palaces and the homes of nobles on their way, and when I was old enough to travel, I joined them.”

Jane imagined the royal retinue making its way around the countryside. “A travelling holiday! Where did you like best?”

The king laughed. “Anywhere that I could get out and ride or swim or play!”

Of course, Jane thought, his memories of those travels were all from when he had been a child. He couldn’t have been more than about twelve when his father’s royal standard had been raised at Nottingham for a battle that both sides had hoped in vain might settle the king’s quarrel with Parliament.

“And during the wars?” Jane asked.

“I was with my father to begin with, headquartered in Oxford, and moved where he moved. Then when I was not quite fifteen, I was made general of the Western Association, and went to take up my duties in Bristol.”

“A general at fourteen?” Jane asked in amazement.

“In name only, to speak truly. My cousin Rupert was really in command, but I learned much from him, and it was the start of making me into a man. And a king.” His voice was sad, and no wonder, Jane thought.

“And then?” she asked.

“Then we lost Bristol, and I moved westward into Cornwall, and then to the Scilly Isles and thence to Jersey, and then to France and the Low Countries. The next time I set foot on English soil was when I crossed the border from Scotland a month ago.”

“But you’ll be back,” Jane whispered fiercely to him. “I know you will.”

“I will,” he nodded, straightening in the saddle. “But God knows when or how.”

They rode on in silence for a little way. Jane watched a flock of sparrows swoop overhead, then plunge and divide, settling on the branches of a large sycamore.

“Will you sing to me, Jane?” Charles asked. “Your good spirits cheer me.”

Jane began to sing “Come o’er the Bourne, Bessy”. Henry slowed his horse to come alongside them, and sang the man’s part as they came to the second verse.

“I am the lover fair

Hath chose thee to mine heir,

And my name is Merry England.”

Charles laughed in delight as Jane sang in response.

“Here is my hand,

My dear lover England,

I am thine with both mind and heart.”

THE MORNING WAS BLESSEDLY UNEVENTFUL COMPARED TO THE PREVIOUS day’s ride, and at midday they stopped beneath a huge oak tree to eat. Jane was very conscious of Charles’s hands on her waist as he helped her to dismount, and she could feel her cheeks going pink at the vivid memory of his lips on hers the previous night.

“I had a close call of it last night,” Charles said when they were settled comfortably with their meal spread on a blanket, and Jane’s heart skipped before he broke into a smile.

“The cook told me to wind up the jack,” he said, taking a swallow of ale from the leather bottle. “And I had not an idea what she meant.”

“Oh, no,” Jane laughed. “It’s a spit for roasting meat, that winds up like a clock.”

“So I know now, but she must have thought me a thorough idiot when I looked around the room to see what she could mean. She pointed to it, and I took hold of the handle, but wound it the wrong way. Or so she told me, with a glower and a curse. ‘What simpleton are you,’ she asked, ‘that cannot work a jack?’ I thought quick and told her that I was but a poor tenant farmer’s son, and that we rarely had meat, and when we did, we didn’t use a jack to roast it.”

Henry laughed, but it was to Jane that Charles was looking with a smile on his face.

AS AFTERNOON DREW TOWARDS EVENING, A TALL CHURCH SPIRE rose in the distance ahead.

“That will be Cirencester,” Henry said. “The Crown Inn is said to be friendly and comfortable, though right at the marketplace and heavily travelled.”

“Then the Crown it is,” Charles said. “I’ll keep to the room and keep my head down when I must pass among strangers.”

The Crown lay just off the main road and only feet from the medieval stone church. As they rode into the inn yard, Jane was alarmed to see that it was full of soldiers and that another party of troopers were right behind them.

“Never fear,” Charles murmured, dismounting. “Leave it to me.”

He helped her to the ground, and after an exchange of glances, Henry tossed him the reins of his horse as well. To Jane’s astonishment, Charles swaggered forward into the crowd of red-coated soldiers, bumping into shoulders, stepping on feet, and provoking a hail of oaths as the men scrambled to avoid being trampled by the horses.

“Have a care, you clotpole!”

“Poxed idiot!”

Jane made to step forward, but Henry’s hand on her arm stayed her. Charles glanced around as if in astonishment, his mouth gaping open.

“Beg pardon, your worships.”

His accent was thickest Staffordshire, as if he had grown up in the country around Bentley Hall. A burly sergeant, tall but not so tall as Charles, shoved him hard and glowered at him.

“You whoreson fool! Do you need teaching manners?”

He pulled back his fist, and Charles flinched as though in fear.

“Kick him like the dog he is, Johnno,” another soldier called, and there was a chorus of laughs.

Charles plucked his hat from his head and hung his shoulders in sheepish apology.

“I’m sorry, your worship. Most sorry, sir.”

Johnno stood sneering at him, as if deciding whether to strike him or not, but then shrugged.

“Well, get on with you, then. And let it be a lesson to you for next time.”

“Oh, yes, sir,” Charles said, tugging at his forelock and grinning like a child reprieved from a whipping. “Thank you, sir.”

Nodding at the muttering soldiers to either side of him, he ambled towards the stable with the horses.

“I still say you should have thrashed him,” a second sergeant called out to Johnno.

“Not worth dirtying my coat.”

The men laughed, and turned their attention back to whatever they had been doing when they were interrupted.

“WITH ALL THESE SOLDIERS I’VE ONLY BUT TWO ROOMS LEFT,” THE landlord said. “And not even room for your servant in the stable. He’ll have to sleep on a pallet in your room, sir.” He had witnessed the scene in the stable yard, and grinned at Henry. “Perhaps it’s just as well you keep the fool out of harm’s way.”

They ordered food to be brought upstairs rather than going down to the taproom to eat, and by the time Jane had washed her face and hands, the men were already waiting in Henry’s room. Charles, in breeches and shirtsleeves, was lounging on a chair near the fire, his long legs stretched before him and his feet propped on a stool. He looked like a great cat, Jane thought, watching the play of his muscles beneath the linen of his shirt. There was something catlike about the glint in his eyes, too, as he gave her a lazy smile.

“Well,” he grinned. “I reckoned that blundering among the troops would anger them so that they’d not think to look beyond their rage, and so it did. But the ostler had keener eyes. As soon as I came into the stable, I took the bridles off the horses, and called him to me to help me give the horses some oats. And as he was helping me to feed the horses, ‘Sure, sir,’ says he, ‘I know your face.’”

Jane gasped and Henry looked at him in alarm, and Charles nodded wryly.

“Which was no very pleasant question to me, but I thought the best way was to ask him where he had lived. He told me that he was but newly come here, that he was born in Exeter and had been ostler in an inn there, hard by one Mr Potter’s, a merchant, in whose house I had lain at the time of war.”

“What ill luck!” Henry exclaimed.

“I thought it best to give the fellow no further occasion of thinking where he had seen me, for fear he should guess right at last. Therefore I told him, ‘Friend, certainly you have seen me there at Mr Potter’s, for I served him a good while, above a year.’ ‘Oh,’ says he, ‘Then I remember you a boy there.’”

Jane laughed at Charles’s impersonation of the ostler, nodding in sage satisfaction.

“And with that,” Charles continued, “he was put off from thinking any more on it but desired that we might drink a pot of beer together. Which I excused by saying that I must go wait upon my master and get his dinner ready for him, but told him that we were going for London and would return about three weeks hence, and then I would not fail to drink a pot with him.”

“Quick thinking, Your Majesty,” Henry grinned.

A knock at the door heralded the arrival of dinner. Once the kitchen boy was gone, Jane made to serve Charles, but he waved off her attentions and begged her and Henry to sit and eat with him.

Riding pillion for so many miles was wearying, and Jane’s body ached in unaccustomed places. The men appeared exhausted as well, and hot food and warmed wine brightened their spirits and revived their energy.

“Do you know”—Charles smiled over a leg of chicken—“I begin to think that I may be safe after all. Only one more day of riding, and we shall be at Bristol.”

“And nothing will hinder us from getting you there, Sire,” Henry said, “though it costs my life.”

Charles looked from Jane to Henry. “I can only hope that I will see the day when I can honour you as I wish for the help you have given me. I have been much humbled by the love and care shown to me by so many of my people these last days. Most of them have been poor folk with little enough for themselves, but they’ve risked their lives to keep me safe, and offered all they have. Indeed, one of them gave me the shirt off his back, quite truly.”

He plucked at his shirt, now grimy from the ride but clearly new.

“The people love you, Your Majesty,” Jane said. “And pray for your return.”

But none of them love you so well as I do, she thought, watching the flickering firelight play on his face.

Charles looked around the room, cosy with the fire crackling, its light chasing the shadows away, and smiled.

“A bed to sleep in tonight! I will ne’er take such comfort for granted again.”

“Of course you shall have the great bed, Your Majesty,” Henry said, “and I will take the pallet.”

“Even a pallet would be welcome,” Charles laughed, “and a great improvement from doubling myself up in priest holes, and a day spent sleeping in a tree.”

“In a tree?” Jane asked in astonishment.

“Yes,” Charles said. “When I was at Boscobel, the Giffards feared I would be discovered if I stayed within, even in the priest hole, so I spent a long day in an oak some little way behind the house, my head resting upon the lap of one Colonel Carlis, who I think you know?”

“Yes, an old friend,” Jane said.

“Cromwell’s men were searching in the woods nearby, and it scarcely seemed possible that we should escape detection. And yet despite all that, I was so tired, having gone three nights without sleep, that I slumbered, my head resting on the good colonel’s lap.”

“Will you tell us of the fight at Worcester, Your Majesty?” Henry asked, pouring more wine for all of them. “We’ve only heard pieces of the story, and none from any who know what happened so well as you.”

Charles’s eyes darkened, and Jane thought of the stories of confusion, despair, and horror she had heard from the soldiers fleeing from the battle.

“It was a desperate venture, in which people were laughing at the ridiculousness of our condition well before the battle. We had been three weeks marching from Scotland, with the rebels pursuing us, when we limped into Worcester. We knew Oliver was on his way with thirty thousand men, and I had but half that number, hungry, sick at heart, already worn out, many lacking even shoes to their feet.”

Jane thought of the ragged survivors on the road past Bentley the day after the battle. It was a wonder any had survived at all, she thought, if they had begun in such desperate condition.

“We needed every advantage we could get. We blew up the bridges leading to the town, dug earthworks, built up the fort, and waited. When at length Cromwell came, he fired upon the city, but made no further move for three days.”

Charles was on his feet now, pacing. Jane could imagine only too well the tension of the young king and his soldiers, knowing the battle would come but not when, having to stay vigilant and ready despite their exhaustion and apprehension.

“He was waiting, you see, for the third of September.” Charles turned to them, a bitter smile creasing his face. “A year to the day since he beat us at Dunbar. And when that day dawned, he moved.”

“John Lane and I were on our way to Worcester on that day, even as the fight was under way,” Henry said. “I would we had reached you in time to be of use.”

“I would you had, too. Had we had but a few thousand more so stouthearted, perhaps the fight would have ended differently.”

He leaned a hand on the mantelpiece and stood staring down into the fire. Jane tried to imagine how a battle started.

“How did it begin? How did you know what to do, how to place your men?” she asked.

“I began the day atop the cathedral with my officers,” Charles said. “Where we could see for miles in every direction. My heart was in my throat, I can tell you, to see the enemy off to the south, so numerous.”

Jane’s throat tightened to think what he must have felt, seeing the possibility of death and destruction marching inexorably towards him.

“I cannot say whether our hopes or fears were greatest that morning, but we had one stout argument—despair. For we knew that everything rested on the outcome of that day, and for me it would be a crown or a coffin. I took a last look at that great sweeping view, the wind on the river, my men massed and waiting, and went down to fight.”

Jane pictured him, mounted and armed, raising his sword aloft, rallying his men to battle.

Follow your spirit; and upon this charge

Cry “God for Harry, England, and Saint George!”

“If bravery and determination alone were enough, you would have won,” she said.

“You held the fort and the city walls for most of the day, did you not, Your Majesty?” Henry asked.

“So we did. The tide turned, alas, when they overran the fort, and turned our guns against us. The Duke of Hamilton, who led the Scots so valiantly, was grievous wounded by a cannonball.”

Jane winced. A cannonball could easily take off a man’s head or cut him in two.

“His men held off the charge at Sidbury Gate as long as they could, but once the enemy was within the city walls, the day was lost.”

“My lord Wilmot says he never saw a fiercer fight,” Henry said.

“My men made a last stand near the town hall, and I hope I may never see such a sight again as the red of the setting sun on the blood in the streets. But it just gave me time to get to my headquarters, cast off my armour, and bid Wilmot to meet me outside the gate with fresh horses if it could be done. As it was, I heard them breaking down the front door even as I slipped out the back, and though it was only steps to St Martin’s Gate, it was a near thing that I got out.”

His look of bleak despair chilled Jane’s heart, and she wished she could take him into her arms and comfort him.

“There was no other way, surely,” she said, “but for you to fly?”

“No,” Charles agreed. “My life and any hope for the future of the kingdom would have been lost had I tarried but five minutes longer. Outside the walls, Wilmot and I encountered some of our troops. I tried to rally them to go back and try once more, but it was no use, and it would probably have done little but let me die fighting instead of fleeing.”

The fire was burning low, and Jane was exhausted with the day’s riding. She longed for a minute alone with Charles, but there seemed no graceful way to manage it, so she rose to leave. Charles’s eyes met hers, and she felt their heat.

“Let me light you to your room, Mistress Jane,” he said, picking up the candle from the table.

“I’ll do it, Your Majesty,” Henry said, rising.

“Sit, Lascelles,” Charles said, and it was not a request. “I said I’ll light the lady’s way.”

Henry bowed his head in assent, though Jane could practically hear the questions and protests in his mind.

“Good night, Henry,” she said demurely, not meeting his eyes. “I’ll see you on the morrow.”

Candle in hand, Charles led the way down the passage. He loomed before her in the darkness, the candlelight silhouetting him in its golden glow. In a moment they would be alone. Her heart beat faster at the thought of his arms around her, his mouth on hers. But to Jane’s disappointment, when they got to her room he opened the door for her but did not follow her inside. She looked up at him, not quite daring to reach out a hand to touch him, to tilt her head back and draw him into a kiss. He took her hand, turned it over, and the feel of his lips on her palm made her belly contract with desire.

“I’ll go back to your cousin now, sweet Jane.”

No, Jane thought, don’t go.

Charles smiled and stroked her cheek, as if reading her thoughts. “Henry has hazarded his life for my safety, and I would not cause him unease or make him think I regard you with less than honourable respect, which indeed I do not.”

“Then good night, sir,” Jane said, turning.

“But, Jane,” Charles said, stopping the door with his foot, “I’ll see you in my dreams, make no mistake.”