Читать книгу Trekking in the Apennines - Gillian Price - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Your peaks are beautiful, ye Apennines!

In the soft light of these serenest skies;

From the broad highland region, black with pines,

Fair as the hills of Paradise they rise.

To the Apennines, William Cullen Bryant, 1835

The mountainous Apennines, without a doubt, are Italy’s best-kept secret. Forming the rugged spine of the slender Italian peninsula, they seem to provide support as it ventures out into the Mediterranean. For walkers this glorious elongated range provides thousands of kilometres of marked walking trails over stunning panoramic ridges and stupendous forested valleys, touching on quiet rural communities little affected by mass tourism. Dotted throughout are historic sanctuaries, hospitable mountain inns, national parks and nature reserves home to wildlife and marvellous wildflowers, incredible roads and passes that testify to feats of engineering, and stark memorials to the terrible events of World War II.

The Apennines

The Apennine chain runs along the entire length of Italy and clocks up some 1400km from the link with the Alps close to the French border, all the way south to the Straits of Messina, even extending over to Sicily. The highest peak is the 2912m Corno Grande in Italy’s southern Abruzzo region. As a formidable barrier that splits the country in two lengthways, the range has witnessed centuries of wars and skirmishes, alternating with the passage of traders, pilgrims and daring bandits.

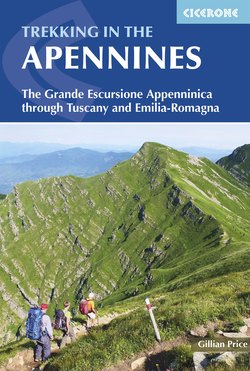

Heading towards Libro Aperto (Stage 15)

The rock is, by and large, sedimentary in nature – sandstone, shale and some limestone – deposited in an ancient sea during the Mesozoic era (245–66 million years ago). The mountains were formed immediately after their neighbours, the Alps, when – some 66 million years ago, and climaxing around two million years BCE – remnants of the African plate were forced together and squeezed upwards, little by little.

Both volcanic and seismic activity shaped the Apennines, though ancient ice masses also played a part. Tell-tale clues are sheltered cirques like giant armchairs, once filled by ice from a glacier tongue and nowadays more often than not home to a lake or tarn. The present aspect of the Apennines – steep, rough western flanks overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea, in contrast to the relatively gentler slopes on the eastern Adriatic side – is due mainly to recent erosion by water.

Evidence has been unearthed of man’s presence since prehistoric times, some 7000 years ago. The northern Apennines were then the stronghold of the ancient Liguri or Ligurian people (as the colonising Romans found out to their detriment over the 150 years it took to get the fierce tribes to accept domination). We are probably indebted to them for the very name Apennines: the root ‘penn’ (for an isolated peak) is found throughout Italy. In another version Pennine was a divinity believed to reside on the inhospitable summits, while a further interpretation attributes the name to King Api, last of the Italic gods.

Over time well-trodden paths conveyed waves of passers-by, such as devotees on the Via Francigena which led from Canterbury to Rome. For the great medieval poet Dante Alighieri, the Apennines were a source of inspiration for ‘The Divine Comedy’; the same holds true for Petrarch and Boccaccio. German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, revelling in sun-blessed Italy, was heading south towards Rome in October 1786, and wrote: ‘I find the Apennines a remarkable part of the world. Upon the great plain of the Po basin there follows a mountain range that rises from the depths, between two seas, to end the continent on the south…it is a curious web of mountain ridges facing each other.’

From their base near the Tyrrhenian coast, both Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley were inspired by the Apennines, which made appearances in their respective works Valperga and ‘The Witch of Atlas’.

The ‘romantic’ wild woods and mountainous ridges were long the realm of smugglers, woodcutters and charcoal burners. The latter were renowned as a wild mob who moved from camp to camp erecting huge compact mounds of cut branches that underwent slow round-the-clock combustion. Their circular cleared work platforms are still visible. Plaques recording the passage of indefatigable Giuseppe Garibaldi are not unusual. Instigator of the unification of northern Italy with Sicily and the south in 1861 under the Kingdom of the House of Savoy, he crossed the Apennines on one of his campaigns, his ranks swelled by Robin Hood-style bandits in revolt in the Romagna region against harsh taxes and the Austrian occupation.

Lovely Lago Scaffaiolo (Stage 14)

The central and northern Apennines were subjected to widespread devastation in the latter years of World War II. Once fascist Italy had recapitulated and signed a peace agreement with the Allies in 1943, the Germans turned into occupying forces and dug themselves in to prepare for the inevitable advance which thankfully led to the liberation of the whole country in 1945. Massive defences were constructed in 1944 – the so-called Gothic Line – that stretched coast-to-coast across the peninsula, entailing drastically clearing ridges to enable control of strategic passes along with key communication routes. Although a sea of green has now all but obliterated signs of battle, there are poignant reminders in the shape of war cemeteries and memorials to the Italian partisans, former soldiers who sprang into action after the armistice, working closely in liaison with Allied servicemen parachuted in behind the lines.

The GEA trek

The trek described in this guide is a memorable long-distance journey on foot snaking its way through the central and northern section of the Apennines. The Grande Escursione Appenninica or GEA (pronounced ‘jayah’ in Italian) spends a total of 23 wonderful days covering a little over 400km (402.6km to be precise), approximately a third of the total length of the Apennine chain; it moves across altitudes ranging between 400 and 2054m above sea level. Accommodation en route is in comfortable guesthouses and alpine-style refuges.

Starting in eastern Tuscany on the border with Umbria and the Marche, the trek progresses northwest to make a number of forays into Emilia-Romagna – with marked changes in accents and cuisine – before heading inland parallel to the Tyrrhenian coast on its way north to the edge of Liguria.

Marvellous views over the Garfagnana to the Alpi Apuane (Stage 17)

The route was conceived in the 1980s by Florentine walking enthusiasts Alfonso Bietolini and Gianfranco Bracci, though many improvements have since been implemented. The walking is straightforward, on paths, forestry tracks and lanes with constant waymarking, making the GEA suitable for a broad range of walkers. In the northern part the odd brief tract negotiates exposed crest, mostly avoidable. The terrain ranges from rocky slopes and open windswept crests, thick carpets of flowered meadows through to woods, where layers of leaf litter provide a soft cushion for tired feet and the play of sunlight serves as distraction from fatigue. Almost every day road passes and villages served by local transport are touched on, enabling walkers to slot in or bail out at will, to fit in with personal holiday requirements.

The initial southernmost sections of the GEA traverse the 364 sq km Parco Nazionale delle Foreste Casentinesi, which boasts magnificent spreads of ancient chestnut, fir and beech wood lovingly nurtured over the centuries by monks. Here at times the route coincides with pathways taken by Saint Francis as he tramped the hills setting up isolated retreats and spreading his message of simplicity. Nowadays groups of pilgrims follow in his footsteps on their way to Assisi. The second, more elevated part of the trek where the Apennines overlook the intensively cultivated Po plain, comes under the auspices of the fledgling 240 sq km Parco Nazionale dell’Appennino Tosco-Emiliano, dotted with sparkling lakes, formed in ancient times by long-gone glaciers.

Highlights and shorter walks

The GEA is well suited for biting off sizeable chunks as single or multiple-day walks thanks to the excellent network of public transport that serves the Apennine villages and passes. To facilitate walkers who don’t have 23 days available for the entire trek, a selection of shorter sections encompassing highlights is outlined here. Each begins and ends at a location served directly by public transport (or within reasonable distance). In the absence of a bus, you can always ask at a café or hotel for a local taxi.

1 day Badia Prataglia–Camaldoli (Stage 5). Straightforward paths climb through divine woods to a broad ridge, whence a plunge to a landmark historic sanctuary and monastery.

1 day Passo del Giogo–Passo della Futa (Stage 10). A roller-coaster day that concludes at a poignant World War II German war cemetery.

1–2 days Montepiano–Rifugio Pacini–Cantagallo (Stages 12 and 13). Studded with shrines this wander through the vast sea of rolling green hills is a delight in springtime.

2 days Badia Prataglia–Rifugio Città di Forlì–Passo del Muraglione (Stages 5 and 6). A rewarding mini-trek through the Casentino National Park, taking in forests, high peaks and scenic crests, not to mention some good hospitality.

2 days Pracchia–Lago Scaffaiolo–Abetone (Stages 14 and 15). Exhilarating if tiring stretch that negotiates both beautiful woodland where deer abound and breathtaking open ridges, touching on two key peaks.

2 days Boscolungo (Abetone)–Lago Santo Modenese–San Pellegrino in Alpe (Stages 16 and 17). Some marvellous panoramic ridge walking, a justifiably popular lake resort and a historic sanctuary as the final destination.

2 days Prato Spilla–Lago Santo Parmense–Passo della Cisa (Stages 21 and 22). Plenty of open ridge with massive sweeping views, while myriad attractive lakes nestling in cirques provide good excuses for a detour. It takes in one of the best sections of the entire trek.

3 days Passo delle Radici–Passo Pradarena–Passo del Cerreto (Stages 18 and 19). Another unbeatable ‘top’ section that boasts brilliant views, the highest peak in Tuscany and the GEA, and premium bilberry ‘orchards’.

Monte Prado, the highest peak in Tuscany

PROMINENT PEAKS IN THE NORTHERN APENNINES

The following panoramic peaks are all included in the trek or reachable via a brief detour:

1520m Poggio Scali (Stage 5)

1657m Monte Falco (Stage 6)

1945m Corno alle Scale (Stage 14)

1936m Libro Aperto (Stage 15)

1935m Alpe Tre Potenze (Stage 16)

1964m Monte Rondinaio (Stage 16)

1780m Cime del Romecchio (Stage 17)

1708m Cima La Nuda (Stage 18)

2054m Monte Prado (Stage 18)

1895m Monte La Nuda (Stage 19)

1859m Monte Sillara (Stage 21)

1851m Monte Marmagna (Stage 22)

1830m Monte Orsaro (Stage 22)

Wildlife

Roe deer and timid fallow deer are numerous all along the Apennine chain and are easy to spot grazing on the edge of woods in the early morning and late afternoon. Majestic red deer are more rarely seen, mostly in the heavily forested Parco Nazionale delle Foreste Casentinesi. Originally introduced from northern Europe in the 1800s in the interests of the game reserve belonging to the Grand-Duke of Tuscany Leopold II, their numbers were boosted in the 1950s and the population, now estimated at around two thousand, is the largest in the whole of the Apennines.

A more recent arrival is the marmot, which hails from the Alps. Modest colonies can be observed in the northern Apennines at elevations between 1000 and 2000m. A burrowing rodent resembling a beaver or ground hog, its habitat is stony pasture slopes. The trick in spotting these cuddly comical creatures is to listen out for the piercing shriek of alarm from the sentry on the lookout for eagles, their sole enemy. Marmots spend the summer feasting on flowers and grass with the aim of doubling their body weight in preparation for hibernation around October; they re-emerge in springtime.

Inquisitive goats and horses check out walkers on the GEA

Then there is the wild boar, a great nuisance in view of the inordinate damage it wreaks, rooting around in cultivated fields and woodland. Scratchings, hoofprints and ripped-up undergrowth along with curious mudslides are commonly encountered signs of its presence, though the closest most walkers will get to one is stewed on a restaurant plate at dinnertime as, despite their reputation for fierceness, they are notoriously reticent. The thriving modern-day population is the offspring of prolific Eastern European species introduced to supplement the native population for the purposes of hunting, a collective sport practised with unflagging enthusiasm since Roman times. In adherence to a strict calendar – usually in the November–January period – vociferous armed groups tramp hillsides and woods with yapping dogs sniffing out the elusive creatures.

In woodland the eccentric crested porcupine is not uncommon, but incredibly timid (not to mention nocturnal). Its calling cards are striking black-and-cream quills found on many a pathway, often denoting a struggle with an optimistic predator. The ancient Romans, ever the epicures, brought it over from Africa for its tasty flesh, a great delicacy at banquets (along with dormouse).

Anti-social badgers, on the other hand, leave grey tubes of excrement, but in discreet spots, unlike the foxes whose droppings adorn prominent stones. One of the few forest dwellers active in the daytime is the acrobatic squirrel, easily seen in mid-flight scrambling up the trunk of a pine. The clearest sign of their presence are well-chewed pine cones together with a shower of red scales at the foot of the trees.

In the wake of centuries-long persecution due to fear and ignorance, combined with increasing pressure by man destroying forests and enlarging settlements and pasture, wolves disappeared completely from view in the 1960s. However, sightings of these magnificent creatures are now regular occurrences along the Apennine chain as the population has expanded successfully northwards, recent studies confirming their safe arrival in the Alps. Rather smaller than their North American cousins, the Apennine males weigh in around 25–35kg. Their coat is tawny grey in winter with brown-reddish hues in the summer period. They were afforded official protection as of the 1970s. Stable packs have been reported since the 1980s, aided by the increase in wildlife, and therefore food: wild boar is their favourite prey, though they do not disdain roe deer, sheep and other livestock, for which shepherds receive compensation. Look out for their droppings – dark boar hairs account for the pointy extremity.

Darting lizards such as the eye-catching bright-green variety scuttle through dry leaves, warned off by passing walkers. At the opposite end of the speed scale is the ambling but unbelievably dramatic fire salamander, prehistoric in appearance and splashed yellow and black. Long believed capable of passing unharmed through fire, it inhabits beech woods and damp habitats, the females laying their eggs in streams. A rare relative is the so-called ‘spectacled’ salamander, endemic to the Apennines, and recognisable by yellow-orange patches on its head.

Tiny Lago Martini is passed on the way to Passo del Giovarello (Stage 21)

Birds include the omnipresent cuckoo, a constant companion, as well as squawking European jays flying between the treetops, bright blue metallic plumage glinting, sounding the general alarm for other creatures of the woodland. The elusive woodpecker can be heard rat-tat-tatting rather than be seen. Huge grey-black hooded crows are common in fields, as are colourful pheasants which give themselves away with a guttural coughing croak. Nervous ground-nesting partridges take flight from open bracken terrain with an outraged loud, clucking cry.

Birds of prey range from small hawks and kestrels through to magnificent red kites and buzzards, and even the odd stately pair of golden eagles on rocky open ground. But the overwhelming majority are the thousands of ‘invisible’ songbirds chirping and whistling overhead as you make your way through the woods; early spring is the best time to see them before the trees regain their foliage. In contrast open hillsides are the perfect place to appreciate the skylarks, their melodious inspirational song sheer delight, though more often than not they will be upset by the presence of intruders and make frantic attempts to distract attention from their ground nests. On a warm summer’s day huge screeching numbers of house martins, swifts and swallows form clouds around high summits, attracted by the insects conveyed upwards by air currents; they are also commonly seen in villages, as they swoop below eaves and clay-straw nests sheltering their ever-hungry youngsters.

On sunny terrain, especially in the proximity of abandoned shepherds’ huts and farmland, snakes may be seen preying on small rodents or lizards. The grey-brown smooth snake, green snake and a fast-moving coal-black type are harmless, though the common viper or adder, light grey with diamond markings, can be dangerous if not given time to slither away to safety. Remember that it will only usually attack if it feels threatened. While not especially numerous, the viper should be taken seriously as a bite can be life-threatening. In the unlikely event that a walker is bitten by a viper (vipera in Italian), immobilise the limb with broad bandaging and get medical help as fast as possible – call 118.

Old paved way above Boscolungo (Stage 16)

At medium altitudes, a postprandial stroll through light woodland on a balmy summer’s evening may well be rewarded with the magical sight of fireflies in the undergrowth.

A special mention goes to the humble red wood ant, easily observed in the Abetone forest. They construct enormous conical nests in coniferous forests, which they then protect by devouring damaging parasites. The nests are home to hundreds of thousands of workers which can live up to the venerable age of 10 years, and queens that can survive to the ripe old age of 20!

Last but not least, mention must be made of ticks (zecche in Italian). While not exactly in plague proportions, they should not be ignored as the very rare specimen may carry life-threatening Lyme disease. Ticks prefer open areas where grass and shrubs grow and they can attach themselves to warm-blooded animals or walkers. A good rule is to check your body at the end of the day for tiny foreign black spots, an indication they may be gorging themselves on your blood. Remove the creature carefully using tweezers – avoid the temptation to employ a twisting motion, and be sure to get the head out – and disinfect the skin. Recommended precautionary measures include wearing long light-coloured trousers, tucked into socks, and spraying boots, clothing and hat (but not skin!) with an insect repellant containing Permethrin. More information is available at www.lymeneteurope.org. Doctors consulted will usually prescribe a course of antibiotics as a precautionary measure. Another line is to keep an eye on the affected skin for a week or so and seek medical advice if any swelling or unusual irritation/itching appears.

Plants and flowers

The plant life in the Apennines is essentially Mediterranean in nature. Generally speaking the southern domains are characterised by Turkey oak and evergreen lentisks with spreads of scrubby maquis, gradually replaced by woodlands of beech, pine and chestnut the further north you go. Beech is predominant from the 900m mark and can be seen growing as high as 1700m. This is a guarantee of memorable colours both in spring with a delicate fresh lime green, then a continuum of vivid reds, oranges and yellows in autumn. A brilliant contrast is provided by the darker plantations of evergreens, silver fir and spruce. The most memorable forests are to be found in the Casentino (Parco Nazionale delle Foreste Casentinesi), long exploited for shipbuilding: over the 16th to 19th centuries trunks with a minimum girth of 6m and a height of 28m were dragged by teams of oxen to the River Arno and floated via Florence to Pisa to become masts for the navy. In the 1300s timber was also used as scaffolding for Florence’s monumental duomo. Lower down, starting at 400m, are spreading chestnut woods, long cultivated as the mainstay of many an Apennine community for both timber and fruit, once dried and ground into nutritious flour.

Clockwise from top left: orange lily, lady orchid, broom, blue gentians, houseleeks

In the wake of the ice ages the northernmost regions of the Apennines were ‘invaded’ by alpine plant types in search of warmer conditions, the spruce and alpenrose being typical examples. Walkers will be surprised at the elevated number of alpine flowers on high altitude meadows and grassy ridges. Burgundy-coloured martagon or orange lilies vie for attention with an amazing range of gentians, from the tiny star-shaped variety through to the fat bulbous exemplar and even the more unusual purple gentian, a rich ruby hue. Clumps of pale pink thrift adorn stony ridges. A rarer sight are glorious rich red peonies, while longer-lasting light-blue columbines are another treat on stonier terrain.

Flower buffs will appreciate the delicate endemic rose-pink primrose, which grows on sandstone cliffs in the northern Apennines, and hopefully the less showy but equally rare Apennine globularia, a creeping plant with pale-blue flowers. Spring walkers will enjoy the colourful spreads of delicate corydalis blooms, wood anemones, perfect posies of primroses, meadows of violets and the unruly-headed tassel hyacinth. Soon afterwards the predominant bloom is scented broom that covers hillsides with bright splashes of yellow. An unusual prostrate version is Spanish broom, with denser and pricklier growth. May to June is usually the best time for orchid lovers, though it will depend on altitude. There’s the relatively common helleborine and early-purple varieties, then the sizeable lady orchid with outspread spotted pink petals resembling a human form, and if you’re in luck the exquisite ophrys insect orchids.

Bare twigs of mezereon or daphne burst into strongly scented flower in spring, though these morph into bright red poisonous berries at a later stage. Damp marshy zones often feature fluffy cotton grass alongside pretty butterwort, its Latin name pinguicula a derivation of ‘greasy, fatty’ due to the viscosity of its leaves which act as insect traps. Victims are digested over two days, unwittingly supplying the plant with the nitrogen and phosphorous essential for its growth, and which are hard to find in the boggy ambience where it takes root.

Oten, the way will be strewn with aromatic herbs – oregano, thyme and wild mint inadvertently crushed by boots scent the air deliciously with pure Mediterranean essences. Grasslands above the tree line are associated with a well-anchored carpet of woody shrubs, notably juniper and bilberry, which spreads to amazing extensions, to the delight of amateur pickers who use them for topping fruit tarts or flavouring grappa.

Chestnuts litter the ground in autumn

Getting there

The handiest international airports for the trek start are at Ancona, Pescara, Pisa and Rome, each with ongoing buses and trains. Genoa and Bologna, on the other hand, are closer to the trek conclusion.

The road pass Bocca Trabaria, where the trek begins, can be reached by bus from either side of the mountainous Apennine ridge thanks to the Baschetti run between Sansepolcro and Pesaro. Otherwise a taxi can come in handy. Pesaro is located on the main Adriatic coast Trenitalia railway line, while Sansepolcro can be reached from Rome via Orte and Perugia thanks to the FCU trains, not to mention Etruria Mobilità bus from Arezzo, which in turn is on the main Florence–Rome railway line.

The trek’s conclusion is Passo Due Santi. The closest bus stop is 5km away at the village of Patigno, pick-up point for the ATN bus to the railway station at Pontremoli from where it is easy to travel on to Bologna, Florence or Rome.

See Appendix B for more information and contact details.

Monte Giovo is reflected in the waters of Lago Santo Modenese (Stage 16)

Local transport

Since time immemorial the Apennines have been criss-crossed by tracks and roads of all sorts linking the Adriatic coast to the Tyrrhenian, and the trek encounters a multitude of road passes and settlements served by public transport. This makes it especially versatile for fitting in with plans for shorter holidays or readjustments on account of unfavourable weather. The capillary bus and train network is reliable and very reasonably priced. Details are given at relevant points during the walk description and timetables are on display at bus stops and railway stations. Bus tickets should usually be purchased beforehand – at a café, newspaper kiosk or tobacconist in the vicinity of the bus stop – and stamped on board. Where this is not possible just get on and ask the driver, though you may have to pay a small surcharge. The transport company websites are listed in Appendix C and can be consulted for timetables. As regards trains, unless you have a booked seat – in which case your ticket will show a date and time – stamp your ticket in one of the machines on the platform before boarding. Failure to do so can result in a fine.

Useful travel and timetable terminology can be found in Appendix B.

When to go

Although the climate in the Apennines is classified as continental, it is subject to the warming influence of the Mediterranean. Summers are generally hot and winters freezing cold. Abundant snowfalls can be expected from December through to March. Thereafter it turns into rain, heavier on the Tyrrhenian side than the Adriatic on account of the moisture-laden winds which blow straight in from the nearby sea.

The GEA was originally designed as a summer itinerary: July–August is the perfect time to go with stable conditions and all accommodation and transport operating. That said, it is important to add that – with an eye on hotel/refuge availability – any time from April through to October is both possible and highly recommended. Early springtime can be divine with fresh, crisp air, well ahead of summer’s mugginess. It’s also a great time to go wildlife watching as the lack of foliage facilitates viewing. Disadvantages at this time of year may include snow cover above the 1500m mark if winter falls have come late, and even the odd flurry, though waterproofs and extra care in navigation can help cope with that.

Dappled sunlight in springtime woodland

May usually brings perfect walking weather, neither too hot nor too cold, though some rain is to be expected. Late September–October is simply glorious, with mile after mile of beech wood at its russet best. On the downside, low-lying cloud and mist are more likely in this season. Encounters with amateur hunters can also be expected in late autumn. Solitary optimists after tiny birds will mostly be camouflaged in hides on ridges and clearings – a polite greeting such as ‘Buon giorno’ (Good day) is in order to alert them to your presence. The chaotic large-scale boar hunts are not held until the midwinter months.

Walking any later than October will increase the chance of inclement weather and hotel closure. The majority of small towns and villages have one hotel operating year-round, but these sometimes restrict themselves to weekends and public holidays in the off-season. Moreover, with the end of Daylight Saving Time at the end of October the days will be too short for the longer stages.

In terms of transport and accommodation, with the odd exception, it is safe to say that Stages 1–13 are suitable from spring through to autumn, whereas the latter part (Stages 14–23) is limited to midsummer as most higher altitude refuges don’t start opening until June.

In terms of Italian public holidays, in addition to the Christmas–New Year period and Easter, people have time off on 6 January, 25 April, 1 May, 2 June, 15 August, 1 November and 8 December. At those times buses are less frequent and accommodation best booked ahead.

Accommodation

There are plenty of comfortable places to stay along the GEA thanks to an excellent string of family-run hotels (most with en suite bathrooms), alpine-style refuges, walkers’ hostels and rooms at monasteries, unfailingly welcoming places at the end of a long day on the trail. These enable walkers to proceed unencumbered by camping gear. Roughly speaking two-thirds of the GEA stages end at a hotel and the remaining third at a refuge. The accommodation options are shown as a yellow house symbol on the sketch maps. All have a restaurant and many offer the mezza pensione half board option. Costing around €40–60 per person this includes overnight stay, breakfast and a set three-course dinner (drinks excluded), invariably an excellent deal. Naturally other options such as B&B are also possible. Foodies may prefer to eat à la carte as a greater range of local specialties could be on offer.

La Verna sanctuary offers accommodation (Stage 3)

Unless otherwise indicated, establishments listed in the route description are open all year round, although off-season can be hit-or-miss as impromptu closures are not unheard of. Whatever time of year you go, don’t turn up unannounced but always phone ahead – or book by email where possible – to check there is a free bed and give them time to cater for you. Be aware that mid-August is peak holiday time in Italy and advance reservation is strongly recommended for hot spots such as Lago Santo Modenese, not to mention rifugi on Saturday evenings in summer, as many put up local walking groups. Lastly, remember that the majority of the road passes are served by buses, enabling you to detour to a nearby village and hotel if need be, an added bonus which gives visitors a rare glimpse into farming communities with vestiges of traditional life.

Dinnertime at Rifugio Lago Scaffaiolo (Stage 14)

The rifugi (plural of rifugio) are marvellous hostel-like huts mostly run by CAI, the Italian Alpine Club, but open to everyone. Reachable only on foot they are manned by a custodian (gestore) and a merry band of helpers and provide bunk beds in dormitories, along with a café and restaurant service; most also have hot showers. CAI cardholders and members of overseas alpine clubs with reciprocal rights are entitled to discounted rates. UK residents can join either CAI or its Austrian counterpart – see Appendix C. A quick note on hut etiquette: walking boots should be left in the entrance hall where slippers or flip-flops are usually available for guests; from 10pm to 6am it’s ‘lights out’ and silence. Unless specified otherwise, guests need their own sleeping sheet and towel.

Hotel at San Godenzo (Stage 6)

A Posto Tappa is the Italian equivalent of the French gîte d’étape walkers’ hostel; only two are encountered on the GEA – in Stages 7 and 13. They offer dorm accommodation and cooking facilities. Two unmanned and basic bivacco huts are also en route – they are always open but you need to be self-sufficient in food, sleeping bag and possibly water. A foresteria, on the other hand, refers to guest quarters at a monastery, though these days this usually translates as hotel-standard facilities.

Carry a stash of euros in cash as credit cards are rarely accepted for payment in the rifugi – unlike the majority of hotels and restaurants. Banks and ATMs in villages en route are listed in the walk description.

Rifugio Mariotti sits on the edge of Lago Santo Parmense (Stage 21)

When using the phone in Italy always include the ‘0’ of the area code, even for local calls. The sole exceptions are toll-free numbers beginning with ‘800’ and mobile phones that start with ‘3’, and the emergency numbers. All attempts at speaking Italian are appreciated – helpful expressions can be found in Appendix B.

Camping

By far the best way to enjoy this trek would be to combine guesthouses and camping out along the way; groceries can be purchased at the villages, and water is available en route. For walkers who prefer the freedom and don’t mind the extra weight, the odd discreet pitch won’t be a problem. A single night is tolerated in the designated national park areas of the Casentino (Stages 4–6) and the Appenino Tosco-emiliano (Stages 18–22). Generally speaking avoid private property and always check where possible. The only designated camping grounds on the route are located near Badia Prataglia (Stage 5), Passo della Futa (Stage 10) and Rigoso (off-route, Stage 20). In any case, early in the season it is a good idea to go equipped with bivvy gear just in case accommodation is not available.

Food and drink

Though it stays in Tuscany for the most part, the trek also takes in corners of the Italian regions of Umbria and Emilia-Romagna, and ends up at the doors of Liguria. Each is renowned for distinctive and memorable cuisine, a wonderful bonus for visitors.

A good rule is to be adventurous and ask the staff what their specialities are. Don’t skip the antipasti (starters) unless you have a particular aversion to bruschetta, crunchy bread rubbed with fresh garlic, a drizzle of olive oil and chopped fresh tomatoes. Then there are crostini, an unfailingly scrumptious assortment of toasted bread morsels piled with pâté, melted goat’s cheese, wild mushrooms or olive paste. Don’t miss Emilian crescentine, also known as ficattole by the Tuscans: lightly fried savoury pastry, akin to soft Indian naan bread, served warm with thin slices of ham, salami or local sausage such as finocchiona, flavoured with fennel seeds. The famous cured Parma ham is prosciutto crudo.

All manner of fresh home-rolled pasta is proudly on offer. One traditional speciality is tortelli (similar to ravioli) con ripieno di patate with a potato or zucca pumpkin filling, or stuffed with creamy but light ricotta cheese and spinach. Ravioli toscani on the other hand are filled with meat and vegetables. They come either smothered in rich pomodoro (tomato) or al ragù, the tomatoey-meat sauce that made Bologna famous, if not al burro e salvia (melted butter with a hint of sage). Widespread are pappardelle al cinghiale, flat ribbon pasta served with a rich pungent sauce of stewed boar, not to everyone’s taste, though a worthy alternative comes with funghi, wild mushroom sauce. Thick homemade bringoli are a spaghetti lookalike that hail from Umbria and come with sauces of vegetables and mature cheese. Freshly grated parmigiano cheese accompanies most pasta dishes.

Polenta, a thick corn porridge that goes well with stews, may be available; leftover pieces are sometimes fried. Towards the end of the trek near Tuscany’s border with Liguria, you’ll encounter testaroli al pesto, simple pasta squares prepared from a batter cooked on a griddle, then softened in hot water prior to serving, and accompanied by an aromatic sauce of olive oil, basil, pine nuts, parmigiano and pecorino cheeses.

Country-style minestrone is a thick flavoursome soup with tons of vegetables, otherwise there’s zuppa di ceci, chick pea soup, or the traditional home-style Tuscan staple zuppa di farro with spelt, a nutty-tasting type of wheat. Zuppa di porcini made with mushrooms is a must-taste.

The second course is almost exclusively meat. One standard is the renowned fiorentina, a mammoth T-bone steak; the locals boast it has to weigh at least one kilo to earn the name. Then there’s lamb which is delicious as crumbed fried cutlets, agnello fritto. Game (selvaggina) is common, possibly boar (cinghiale), pigeon (piccione) or rabbit (coniglio). Cheeses are concentrated on the amazing range of tangy pecorino from sheep, but there are other cow’s milk treats such as rich pungent formaggio di fosso, which has been buried in straw and is often served with honey.

The Pontremoli valley is clearly seen from Monte Orsaro (Stage 22)

Vegetables are usually served as a side dish, contorno, and will depend on the season, verdure di stagione. An insalata mista will get you a mixed salad, with olive oil and vinegar brought separately.