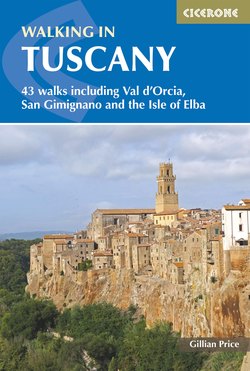

Читать книгу Walking in Tuscany - Gillian Price - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

One of Italy’s largest regions, glorious Tuscany is awesomely beautiful. Everywhere you look are landscapes like paintings, pristine hill villages and hamlets crafted from stone that seem unchanged since ancient times. Gently rolling hills are clothed with fields of golden wheat dashed scarlet by poppies. Winding lanes lined with pencil-straight cypress trees lead to inviting villas with views to picture-perfect hill towns of medieval and Renaissance splendour, recognised as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Walking in Tuscany means all this – and stacks more! The dense forests of the Casentino, rugged mountains of the Apennines and Apuane, Mediterranean maquis backing long sandy beaches in the Maremma on the Tyrrhenian coast, and there’s even the stunning island of Elba, a world of its own.

The tiny lookout on Monte Penna (Walk 16)

Visiting Tuscany on foot is akin to making a voyage through time, as the region is riddled with historical pathways used by traders, pilgrims, armies and travellers since time immemorial. A breath of fresh air for visitors between the crowded art cities, the walks follow in the illustrious footsteps of the ancient Etruscans, the Romans, Hannibal, Saint Francis, Barbarossa, Dante, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Pinocchio, Giuseppe Verdi, Byron, Milton and DH Lawrence – to mention just a few. Oh, food and wine play a big part too.

Thanks to the excellent capillary network of trains and buses, travel around Tuscany is both enjoyable and reliable, enabling visitors to enjoy the scenery without contributing unnecessarily to pollution.

Exploring Tuscany

To help visitors orient themselves, the 43 walks in this guidebook have been grouped into nine areas, each the focus of a separate chapter. Each chapter illustrates the area’s distinctive character and gives a potted history along with essential practical information.

Chapter 1, The environs of Florence, introduces the hilly surroundings of the regional capital, including Medici towns and villas at Fiesole and Artimino, as well as Vinci, home to the great Leonardo.

Chapter 2, The foothills and high Apennines, is a guide to fascinating hills where Pinocchio is star, then the Apennine mountains and rugged ridge walks.

Chapter 3, Alpi Apuane, presents challenging routes in the rugged ‘Alps of Tuscany’.

Chapter 4, Pratomagno and the Foreste Casentinesi, tells of monks and spiritual retreats in age-old forests, with the renowned town of Cortona as an added bonus.

Chapter 5, Chianti, evokes an area that needs little presentation as its picture-perfect vineyards and rolling countryside are famous the world over thanks to the celebrated red wine.

Chapter 6, West of Siena, introduces little-known gems such as Volterra and Sovicille, alongside top tourist choices the walled town of Monteriggioni and San Gimignano ‘of the fine towers’.

San Gimignano and its fine towers (Walk 24)

Chapter 7, The Crete and Val d’Orcia, reveals gorgeous postcard scenery and walks lined with cypresses.

Chapter 8, Elba and the Tyrrhenian coast, describes routes on the divine island of Elba and the adjacent coast, with their heritage of industrial archaeology.

Chapter 9, The Maremma coast and hinterland, embraces an exciting pristine coastal park then quiet inland villages joined by ancient Etruscan ways. Magical places.

See Appendix E for further reading material on Tuscany, including guides to trekking and climbing as well as more general literature.

Plants and flowers

The marvellous array of unusual trees and flowering plants is reason alone for a visit to Tuscany. Of the broad range of vegetation zones, the highest (at around 2000m) verges on alpine, with gentians, thrift and gorgeous lilies. Below are hills covered with woods of conifer and deciduous beech, which is synonymous with the Apennines; delicate cyclamens are a constant presence here too.

At lower altitudes, conifers and beech give way to woodland populated by typical Mediterranean trees such as the evergreen holm oak, or ilex, with its bushy foliage of glossy dark green oval leaves, a great favourite with charcoal burners. It is often in the company of the mastic tree, or lentisc, which has spear-shaped leaves and red-black berries; its resin was the world’s first chewing gum. Cork oaks are also widespread. Their thick fissured bark, impervious to fire, was used by the ancient Romans for sandals and for floaters on fishing nets; nowadays it is stripped for bottle corks every seven years, leaving the bare trunk bright red.

Clockwise from left: the curious fruit and blossom of the strawberry tree; cyclamen thrive in the woods; lavender and trefoil on Elba; fissured bark of the cork oak; olives ripening in autumn; delicate paper-like rock roses flower in spring

Also notable is the so-called strawberry tree, hung with delicate white bell-shaped flowers and, at the same time, clusters of lumpy orange-red fruit balls. The ripe fruit tastes like strawberry, although the second part of its Latin name Arbutus unedo means ‘eat one’, implying that one is enough! Sturdy bushes of tree heather bear tiny sweet-scented bell blooms in springtime: its branches are bound into bunches as brooms for city sweepers.

Majestic stands of pines thrive along the Tyrrhenian coast. The umbrella or stone pine, often bent into sculptured shapes by the wind, provides nutritious nuts, a key ingredient in pesto sauce. Similar maritime pines were planted to reclaim mosquito-ridden swamps and defeat malaria, as well as being an important source of turpentine and timber for boatbuilding.

As flowers go, there’s ubiquitous yellow broom, which scents the air with its distinctive perfume. Another early bloomer is the caper plant, a straggly spiny shrub that covers walls with its pink-white flowers – to be appreciated in haste before they are gathered for pickling. Spring and summer delights include rainbow masses of paper-like Cistus (rock roses) and pink-purple wild gladiolus, not to mention emerald-green wheat fields streaked with the brilliant blue of cornflowers and the red of poppies. Wild orchids come in myriad amazing varieties, from the minuscule Ophrys, so-called insect orchids, to the showy lady orchid and the common purple.

Towards the coast, prolific wild herbs reveal their presence with a pungent aroma or fragrance released when inadvertently trampled or even lightly brushed. The long list features oregano, mint, thyme, rosemary and sage. Sandy beaches and dunes are home to pale lilac sea lavender and to the woolly yellow plants of everlasting, an unassuming plant whose elongated silvery leaves conjure up oriental spices when rubbed, hence its nickname ‘curry plant’.

Late winter also brings delights. As early as February, acacia or wattle trees (of Australian origin) are decorated with dazzling yellow feathers. Fields and woods have black-centred pink-mauve anemones, periwinkles, crocuses, grape hyacinths, intense indigo bugloss, common mallow and the fresh green hellebore.

Last but not least, flanking the extant ‘wild’ vegetation bands, are the cultivated zones where ridges between fields are punctuated with archetypal cypresses. The other omnipresent Tuscan essentials are the olive trees of ancient standing and orderly ranks of precious grapevines.

See Appendix E for suggested further reading for wildflower enthusiasts.

Olive groves

Wildlife

Despite widespread agriculture, sprawling urbanisation and the popularity of hunting, an encouraging number of wild animals and birds inhabit the hills and coast of Tuscany. Both red and fallow deer graze in woodland clearings, easier to spot than the shy Sardinian mouflon with their showy curly horns, which inhabit impossible ridges on the Apennines and the island of Elba.

Thanks to protective 1970s laws, the wolf is making a silent comeback and the population in Tuscany alone is estimated around 500. Canis lupus italicus sports a light brown coat with grey overtones, although unfortunate crosses with dogs are producing variations. Its favourite prey are deer and boar, but it does not disdain sheep. Footprints in damp ground and droppings are pointers for attentive walkers to the passage of this beautiful elusive creature.

Another ‘invisible’ animal is the protected crested porcupine, whose visiting card is the black-and-white quills it scatters along woodland paths. The ancient Romans, ever the epicures, brought it from Africa as a banquet delicacy.

Porcupine quills

In contrast, foxes are a relatively common sight in dew-soaked fields in the early morning. As too is the pheasant, easily identified by its white neck ring and red face, not to mention its raucous ‘sore throat’ call. It was introduced from south-west Asia by hunting enthusiasts.

A multitude of wild boar leave telltale hoofprints in mud as well as upturned stones and diggings. However, despite their fierce reputation, the beasts are notoriously diffident so close encounters are rare. These days, a heftier and more prolific Eastern European boar has replaced the native species. The young ones, shaped like a rugby ball and coloured like a cappuccino with creamy stripes, may venture out alone, but in general the closest a walker will get to one is a stuffed creature in a shopfront advertising its ham! The ancient sport of boar hunting continues in Tuscany, with widespread group hunts in late autumn and winter.

Another immigrant is the comical nutria, or swamp beaver, brought from South America for fur breeding. Escapees have spread through Tuscany; these bulky creatures burrow into riverbanks and are considered a pest.

On the bird front, the eye-catching hoopoe is unforgettable as it runs and bobs its way along the ground. Vaguely like a woodpecker, it has a showy crest of black-tipped chestnut-brown feathers and black-and-white striped wings. European jays are a familiar sight, their bright metallic-blue plumage glinting in the trees. Cuckoos and cooing wood pigeons are also residents of woodland. Birds of prey such as kites, kestrels and hawks are not unusual circling overhead, keeping high above the ubiquitous grey-black hooded crows which inevitably attempt to chase them off.

The Italian branch of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF Italia) has been gradually purchasing land as part of its enlightened policy to extend environmental protection. The coastal oasi (reserves) around Orbetello are an example. Here, the varied bird life includes the black-winged stilt on skinny crimson legs, ospreys, peregrine falcons, crested grebes, bright kingfishers and even showy flamingoes (www.wwf.it/oasi/toscana).

One dog needs a quick mention: the pastore maremmano is a magnificent white-haired creature with a persistent bark. Widely used as sheepdogs or watchdogs on country properties, they are not usually on a leash and it’s a good idea to give them a wide berth. Under no circumstances should walkers approach the flock they are guarding.

The only other warning regards snakes. The poisonous viper with its silvery-grey diamond markings inhabits Tuscany, along with a multitude of harmless relations such as the similar smooth snake. A viper only attacks when threatened so give it time to slither away from the path where it is taking the sun.

To conclude on a positive note, a magical pastime for balmy summer evenings is to go spotting fireflies or glow-worms, a type of beetle. Once the sun has gone down, gardens and waysides come alight with magical flickering pinpoints of greenish-white light, which double as their mating calls.

Getting there

The handiest international airport in Tuscany is Pisa, although Bologna, Perugia and Rome are also useful. All have good bus or train links. Moreover, Tuscany is easily reached from other parts of Italy thanks to high-speed trains on strategic long-distance lines such as Rome–Florence and Milan–Florence, run by Trenitalia and Italo.

A cross marks the turn-off for Villa a Tolli (Walk 27)

Local transport

Public transport in Tuscany is excellent and reliable, fares are reasonable and timetables can be consulted online. All but a handful of the walks in this guidebook can be accessed by public transport and visitors are encouraged to take advantage of this in the name of less polluted air and quieter roads. As regards the routes that do need private transport, hotels and tourist offices will always help arrange for a lift or will contact the local taxi service on behalf of guests who do not have a car.

The railway network is capillary and there are good regional trains, which do not need booking. Should the biglietteria (ticket office) be closed, use the automatic machine. Remember that train tickets need to be stamped before boarding.

Local buses cover just about every corner of Tuscany – although outlying villages may not have a service on Sundays. Where possible, tickets should be purchased before a journey, either at the bus station or at news stands and tobacconists displaying the appropriate logo; they then need to be stamped on board. However, drivers do sell tickets for a small surcharge.

Relevant details are given in the information box at the start of each walk, and transport company websites are listed in Appendix D. Appendix B includes a list of bus/train terminology to help understand timetables.

In the Valle di Pomonte on the island of Elba (Walk 35)

Information

The Italian State Tourist Board (www.enit.it) has offices all over the world and can provide visitors with general information. Masses of useful details about accommodation, transport and much else is available at tourist offices and websites – see Appendix D.

When to go

The beauty of Tuscany is that walking is feasible the whole year round. Each season and altitude offers its delights. Spring (March–May), with perfect outdoor temperatures, is undeniably the most beautiful time for lovers of infinite shades of green along with the first extraordinary expanses of colourful wildflowers. Apart from the Easter break and the long weekends that coincide with public holidays, the areas covered by the walks in this book are unlikely to receive more than a sprinkling of visitors.

Summer (June–August) brings lovely conditions on the coast although not necessarily the best for walking inland, where heat and mugginess can take the pleasure out of it and haze can spoil visibility. Mid August is peak holiday season so the main towns and the island of Elba are inadvisable unless you have advance booking for accommodation and don’t mind extortionate prices, blazing heat and traffic-choked roads. However, this is also the time of year when higher altitudes such as the Casentino forests and the mountainous Alpi Apuane and Apennines come into their own, with pleasant temperatures even in July and August.

Climbing beneath the sheer face of Monte Nona in the Alpi Apuane (Walk 12)

Autumn (September–November) is a very promising season as visitors are few and far between. Italy stays on daylight saving time until the end of October, meaning long walking days (it gets dark around 6–7pm). Foliage can be spectacular, with brilliant reds and hues of yellow and orange during the grape harvests. Leaves scrunch underfoot and in the woods you risk bombardment by falling spiky chestnuts. The sole negative note comes from the Sunday gunshots and yapping dogs who belong to the hunters. November is probably best avoided as it is notoriously foggy.

At lower altitudes, winter (December–February) can be simply superb if chilly, although snow will cover upland routes. Brisk crisp weather is usually the norm. Conditions are excellent for birdwatching along the coast as huge numbers of migrational species stop over. Remember though that days are shorter – expect it to get dark as early as 4.30pm in midwinter.

Accommodation

Tuscany has a huge range of excellent accommodation options, including charming towns and villages, castles and villas.

At the end of each chapter introduction is a short section suggesting suitable bases with accommodation for exploring that particular area, with brief details of transport links too. Suggestions for middle-range hotels and B&Bs, affittacamere (rooms to rent) and walkers’ refuges handy for the walks are given in Appendix C. Most accept internet bookings and credit cards. For a vaster choice, including self-catering houses, agriturismo (farm stays) and campsites, either use an online agency such as www.booking.com or contact the tourist offices listed in Appendix D.

It is not usually necessary to book a long way ahead, with the exception of the Italian public holidays: 1 January (New Year), 6 January (Epiphany), Easter Sunday and Monday, 25 April (Liberation Day), 1 May (Labour Day), 2 June (Republic Day), 15 August (Ferragosto), 1 November (All Saints), 8 December (Immaculate Conception), 25–26 December (Christmas and Boxing Day). Weekends are naturally busier too, especially in the art cities such as Florence and Siena.

When calling an Italian landline, always include the first 0 of the area code. On the other hand, numbers beginning with 3 (mobile numbers) and emergency numbers need to be dialled as they stand, ie without a zero. If ringing from overseas, preface all Italian telephone numbers with +39.

Rifugio Battisti

Food and wine

A guide to Tuscany could hardly be considered complete without at least a passing mention of the vast culinary delights in store for visitors. And walking demands substantial nourishment.

A visit to a fresh produce market is a good introduction to local fare. In addition to the season’s fruit and vegetables, which come in colourful photogenic stacks, suggestions for picnics include tangy ewe’s milk cheese, pecorino, although a request for un formaggio locale (a local cheese) will always turn up something interesting. A must-taste for carnivores is finocchiona, a soft garlicky salami-type sausage flavoured with wild fennel seeds, which melts in the mouth. With a bit of luck there’ll also be an open-sided van selling porchetta, luscious roast suckling pig flavoured with herbs galore and served in thick slices. These can be consumed with the typical saltless bread sold in huge floury loaves at the panificio (bakery). In addition to the markets, delicatessens and supermarkets unfailingly have tempting displays, and most will make up fresh rolls (panini) on the spot with your choice of filling.

Pecorino cheese comes in a range of flavours

Bakeries also have treats suitable for rucksack transport: delicious heavy-duty spicy biscuits such as cavallucci and ricciarelli, or the omnipresent Siena speciality panforte, crammed with dried and candied fruit, honey and nuts.

In restaurants, a good rule is to be adventurous and enquire as to the day’s special: Che cosa avete oggi? Two memorable antipasti (starters) are bruschetta and crostini. The former are thick toasted slices of bread with a hint of garlic, a dribbling of olive oil and some fresh tomato, while the latter are morsels of toast smothered with home-made pâté, sausage, mushroom spread or whatever takes the cook’s fancy that day.

One topping might be fragrant nutty tartufi, namely truffles or earthnuts, edible tuberous fungi that grow underground. They are grated and sprinkled over pasta also such as pici, thick home-made spaghetti. As soups go, you’ll come across acqua cotta, literally ‘cooked water’, a simple tasty brew made with a variety of vegetables, while caciucco consists mostly of fish. Despite its uninviting name, pappa al pomodoro is delicious; this simple thick soup is made with leftover bread, fragrant tomato and basil. Olive oil, preferably the cold pressed extra vergine variety, reigns over the lot.

Game meats such as cinghiale (wild boar) are widespread and found in pasta sauces or hearty stews, an alternative to the legendary oversized Florentine T-bone steak. Tender coniglio (rabbit) features on menus in country trattorias, as does buglione, a deliciously rich lamb and tomato stew. Tegamata di cinta senese translates as a mouth-watering casserole of Siena pork cooked in wine.

Rabbit and fried artichokes are on the menu today

Vegetables are usually served as a side dish (contorno) and will be strictly seasonal. Carciofi fritti are tiny purple artichokes battered and fried, and flavoursome local greens include cicoria (bitter chicory).

Those who make it to dessert may opt for panna cotta, literally ‘cooked cream’, a divine blancmange-type sweet flavoured with caramel or fruit. For a memorable after-dinner treat you can’t go wrong with a handful of cantucci, crisp almond biscuits dunked unabashedly in a glass of sweet, rich, amber-coloured Vin Santo.

And so onto the subject of bottled treats. It’s a tough task, nigh on impossible, trying to sum up the wines of Tuscany in a paragraph…suffice it to say that your taste buds will be extremely happy. A few key place names conjure up wondrous red elixirs: Montalcino, Montepulciano and Chianti (see Chapter 5 for more on this one). Following are brief notes on several of the special names from areas covered in this guide. It’s especially exciting to be taking a walk through the vineyards that produce these memorable wines.

The full-bodied red Brunello di Montalcino (aged in oak barrels for at least four years) must head the list, while those on a budget can enjoy the younger Rosso di Montalcino made with the same grapes. Another one to look out for and hailing from neighbouring hills is the intense Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, first made back in AD790. The Maremma hinterland produces a robust red, Morellino di Scansano, while the island of Elba does a Rosso and a Bianco, which can be a little fizzy but never sweet.

The southern reaches of Tuscany are home to some memorable white wines. A delicate crisp white from tufa country is the Bianco di Pitigliano, while San Gimignano’s superb dry Vernaccia is another: an earlier version of it, presumably fuller-bodied, reputedly prompted Michelangelo to say that it ‘kisses, licks, bites, thrusts and stings’.

What to take

Clothing will depend on the season and personal preferences. In spring and summer, T-shirt, shorts and sun hat are perfect, while winter will mean layers of wool or fleeces with the addition of a windproof jacket, hat and gloves. Long trousers are recommended for potentially overgrown routes. The following checklist might be useful:

Lightweight trekking boots with ankle support or a sturdy pair of trainers with good grip and thick soles to protect your feet from loose stones. Boots are essential on the rocky ground in the Apennines, the Casentino forests, the island of Elba and the Maremma Park. They also come in handy in potentially muddy places like the sunken roadways around Pitigliano.

Day pack. (Shoulder bags or hand-held bags are not a good idea as it is safer to have hands and arms free on the trail.)

Rain gear.

Water bottle.

Swimming costume for coastal routes.

A compass for following maps and identifying landmarks.

Whistle, torch or headlamp (with new batteries) for attracting help in an emergency. (Do not rely on your mobile phone as there is often no signal in outlying places.)

Trekking poles for the mountainous routes; they also come in handy for discouraging overenthusiastic watchdogs.

Binoculars.

Sunglasses, hat and cream.

Basic first-aid kit, including plasters and insect repellent (Italian mosquitoes seem to be especially fond of British skin).

Snack food such as muesli bars or biscuits to tide you over if a walk becomes longer than planned.

The shrine at the fork for Via Poggilarca (Walk 2)

Maps

Topographic maps are provided with each route described in this guide. However, commercial maps showing a greater context and landmarks are also important.

Kompass have put out two useful overlapping collections of 1:50,000 maps for Tuscany. The three-map set n.2439 Toscana Nord takes in the Apennines, Alpi Apuane and the Florence area. The four-map set n.2440 Toscana (‘Heart of Tuscany’) covers Chianti, the Val d’Elsa west of Siena, the Crete, Val d’Orcia and the Tyrrhenian coast.

A handful of more detailed 1:25,000 maps are also available: Edizioni Multigraphic (www.edizionimultigraphic.it) does the Alpi Apuane and the Maremma, L’escursionista (www.escursionista.it) does the island of Elba, and SELCA maps are good for the Apennines and the Foreste Casentinesi.

See individual walks for the sheet numbers of relevant maps. All of these maps are on sale locally in Tuscany. Well-stocked overseas maps suppliers include The Map Shop (www.themapshop.co.uk) and Stanfords stores (www.stanfords.co.uk) in the UK, and Omnimap (www.omnimap.com) in the US; otherwise order from the online Florence bookshop Stella Alpina (www.stella-alpina.com).

DOS AND DON’TS

Don’t set out late on walks even if they’re short. Always have extra time up your sleeve to allow for detours and wrong turns.

Tell your accommodation where you’ll be walking, as a safety precaution.

Find time to get in decent shape before setting out on your holiday, as it will maximise enjoyment. You will appreciate the wonderful scenery better if you’re not tired, and healthy walkers react better in an emergency.

Don’t be overly ambitious – choose itineraries suited to your capacity. Read the walk description before setting out.

Stick with your companions and don’t lose sight of them. Remember that the progress of groups matches that of the slowest member.

Route conditions can change; if you have any doubts about the way to go, don’t hesitate to turn back and retrace your steps rather than risk getting lost. Better safe than sorry.

Avoid walking in brand new footwear as it may cause blisters; on the contrary, leave those worn-out shoes in the shed as they will be unsafe on slippery terrain. Sandals are totally unsuitable for walking in Tuscany.

Check local weather forecasts and don’t start out if storms are forecast. Paths can get slippery if wet, and hills and mountainsides are prone to rockfalls.

Carry weatherproof gear at all times, along with food and plenty of drinking water.

In electrical storms, don’t shelter under trees or rock overhangs and keep away from metallic fixtures.

DO NOT rely on your mobile phone as there may not be any signal.

Carry any rubbish away with you. Even organic waste such as apple cores is best not left lying around as it can upset the diet of animals and birds and spoil things for other visitors.

Close all stock gates behind you promptly and securely.

Be considerate when making a toilet stop and don’t leave unsightly paper lying around. Remember that abandoned huts and rock overhangs could serve as life-saving shelter for someone else. It’s a good idea to carry a supply of small plastic doggy bags to deal with paper and tissues.

Make an effort to learn basic greetings in Italian: buongiorno (good morning), buona sera (good evening), arrivederci (goodbye) and grazie (thank you).

Lastly, don’t leave your common sense at home.

Emergencies

For medical matters, EU residents need a European Health Insurance Card (EHIC). Holders are entitled to free or subsidised emergency treatment in Italy, which has an excellent national health service. UK residents can apply online at www.dh.gov.uk. (If these arrangements change during the life of this book, details will be online at www.cicerone.co.uk in the ‘Updates’ section for this book.) Australia has a similar reciprocal agreement – see www.medicareaustralia.gov.au. Other nationalities need to take out suitable cover. In addition, travel insurance to cover a walking holiday is strongly recommended, as costs for rescue and repatriation can be hefty.

The following may be of help, should problems arise. No charge is made for emergency numbers:

tel 112 for general emergency calls

tel 113 for police (polizia)

tel 118 for health-related emergencies, including ambulance (ambulanza) and mountain rescue (soccorso alpino)

tel 1515 to report forest fires.

‘Help!’ in Italian is Aiuto!, pronounced ‘eye-you-tow’. Pericolo is ‘danger’.

Using this guide

This guidebook contains a selection of 43 walking routes across Tuscany. Visitors wishing to do more – and the choice is huge – should enquire at tourist offices; most of their websites have suggestions as well as offering guided walks.

A steep path winds up from the sanctuary (Walk 16)

The walks in this guide are suitable for a wide range of walkers. There is something for everyone, from easy leisurely strolls for beginners to strenuous climbs for experienced walkers up panoramic peaks. Each route has been designed to fit into a single day. See the route summary table in Appendix A for an overview of the essential data for each walk, including distance (km), ascent/descent (m), grade and approximate walking time.

Many of the routes (but by no means all) are waymarked with official CAI (Club Alpino Italiano/Italian Alpine Club) red-and-white paint stripes together with an identifying number. These are found along the way on prominent stones, trees, walls and rock faces.

CAI waymarking

Each walk description is preceded by an information box containing the following essential data:

Start and Finish.

Distance – in kilometres.

Ascent and Descent – This is important information, as height gain and loss are an indication of effort required and need to be taken into account alongside difficulty and distance when planning the day. Generally speaking, a walker of average fitness will cover 300m in ascent in one hour.

Difficulty – Each walk has been classified by the following grades, although adverse weather conditions will make any route more arduous:Grade 1: an easy route on clear tracks and paths, suitable for beginners. (This corresponds approximately to CAI Grade T: turistico.)Grade 2: paths across hill and mountain terrain, with lots of ups and downs. A reasonable level of fitness is preferable. (This corresponds approximately to CAI Grade E: escursionistico.)Grade 3: strenuous, and entailing some exposed stretches and possibly prolonged climbing. Experience and extra care are recommended. (This corresponds approximately to CAI Grade EE: escursionistico esperto.)

Walking time – This does not include pauses for picnics, admiring views, photos or nature stops. The ‘skeleton’ times given are a guide, as every walker goes at a different pace and makes an unpredictable number of stops along the way. As a general rule, double the times when planning your day.

Map – sheet numbers of relevant maps.

Access – details of how to get to the start of the walk, whether by public transport, on foot or by car.

Chiusure occupies a rather precarious position (Walk 26)

Lovely open terrain below Poggio Barbari (Walk 18)

In the walk descriptions, useful landmarks that appear on the map are given in bold. Altitude in metres above sea level is given as ‘m’, not to be confused with minutes, abbreviated as ‘min’. Approximate timings for sections of each walk are shown in brackets, in hours and minutes.

Finally, see Appendix B for an Italian–English glossary, which lists useful expressions and key vocabulary, including some common words that you might come across on maps, signposts or in tourist literature.