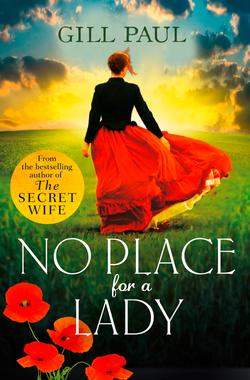

Читать книгу No Place For A Lady: A sweeping wartime romance full of courage and passion - Gill Paul, Gill Paul - Страница 14

Chapter Four

Оглавление24th April 1854

Plymouth Dockyard was teeming with people bustling between precarious stacks of luggage. Tall-masted ships stretched as far as the eye could see. The noise of ships’ horns sounding, street traders crying their wares, and the anxious chatter of bystanders was overwhelming. Lucy worried that they would never find their way but when Charlie hailed a porter and asked him to take them to the Shooting Star, the man seemed confident about finding it. He loaded a trolley with their steamer trunk, all their bags stuffed to bursting, and their large tin bath, and set off. Charlie clutched Lucy’s arm tightly and hurried them through the throng in pursuit of their luggage.

Before long, he spotted some comrades in royal blue and gold Hussars uniform and hailed them, pulling Lucy forwards to introduce her. She shook hands with several gentlemen and was pleased to note their appreciative glances. She had dressed with care in a wide-skirted soft wool gown with cascading ruffles in the skirt, and a warm fitted jacket, both of a deep blue very similar to that of the Hussars’ colours. A prettily trimmed bonnet framed her face.

‘I think you have new admirers,’ Charlie winked, squeezing her hand.

As they approached the ship, she noticed several women sobbing, with young children clinging to their skirts, and asked Charlie what ailed them.

‘These are the soldiers’ wives who can’t come along,’ he told her. ‘There was a ballot and only a few won a place. You’re lucky to be the wife of an officer, as we can all bring our wives, if our commanders agree.’

‘What will become of them while their husbands are away?’ She felt alarmed for their plight. She had no idea what would have happened to her if she hadn’t been allowed to accompany Charlie because his wages were not sufficient, after stoppages for uniform and so forth, for him to have supported her in lodgings like the boarding house where they had been living in Warwick for the last three months. She suspected from the haste with which he insisted they leave that he owed money to the landlady there. If a captain couldn’t manage, how could the soldiers, who earned so much less?

‘I expect their families will look after them,’ Charlie said, as if the question hadn’t occurred to him.

Some called out – ‘Miss, can you help us?’ ‘Need a lady’s maid, Miss?’ – and Lucy cast her eyes down, feeling guilty that she had a place while they did not.

They walked up the gangway onto the ship and followed their porter down to the officers’ deck, where Charlie located their cabin. Lucy swallowed her surprise at how small it was, barely six paces wide and ten long, with a bunk so narrow they would be crushed tight together. There was hardly any hanging space for her gowns, and only one tiny mirror above the washbowl.

‘This is one of the better cabins I’ve seen on a military ship,’ Charlie remarked cheerfully. ‘It’s very well appointed.’

Lucy kept her thoughts to herself. ‘I’ll just unpack a few things, dearest, to make it a little more homely.’

‘In that case, I’ll go and check on the horses on the deck below.’ He kissed her full on the lips and grasped one of her breasts with a wink before he left.

Lucy felt her cheeks flush and she hummed as she arranged their possessions. She liked having someone to look after, loved the intimacy of sharing a bed and eating meals with Charlie. ‘You see, Dorothea?’ she thought. ‘You were wrong!’

Before long, she heard women’s voices in the corridor and popped her head out. The first woman she saw introduced herself as Mrs Fanny Duberly, wife of the 8th Hussars’ Quartermaster. She seemed rather superior in attitude, and moved off after only the briefest ‘hallo’ but not before Lucy had noted that her gown was plain grey worsted and not remotely fashionable. The other woman, Adelaide Cresswell, had a kind face and shook Lucy’s hand warmly.

‘Charlie is a good friend of my husband Bill, so you and I must also be friends, my dear.’

‘Yes, please,’ Lucy cried. ‘I would love that. We women must stick together. I need your advice on how I can support my husband. We are so recently wed I don’t yet know what is expected of an officer’s wife.’

Adelaide smiled and squeezed her hand. ‘I was overjoyed to hear about your marriage. Charlie is a very lucky man. Look how pretty you are! Such lovely china blue eyes.’ She glanced past Lucy into their cabin. ‘Goodness, you’ve brought rather a lot of luggage.’

Lucy looked at the pile. ‘In truth, it was hard knowing what to bring. I’ve had to leave many of my possessions in store,’ she explained. ‘Charlie told me I would need summer clothes, but I also tried to think of items we might need if we have to sleep in a tent.’ She couldn’t contemplate quite how she would manage to change her gowns and perform her toilette in such a cramped space but she was prepared to give it a try if that’s what being an army wife entailed. As well as the tin bath, she had brought some soft feather pillows and a pale gold silk bedspread that used to be her mother’s, so they would have some home comforts.

‘Of course you did – and I’m sure they’ll come in very useful. It’s just that we may have to carry our own luggage at times and your trunk looks rather heavy …’ Seeing Lucy’s alarmed expression, Adelaide added quickly: ‘I expect Charlie will find someone to help you. Now, I was on my way below deck to introduce myself to the women travelling with Bill’s company, the 11th Hussars. Perhaps you would like to come and meet the wives of Charlie’s men? There’s plenty of time as the ship won’t leave harbour till after dinner.’

Lucy’s eyes widened. ‘I’d love to!’ It hadn’t occurred to her that Charlie had men beneath him, men who obeyed his commands, but she supposed as a captain that he must. She was anxious to give the right impression and decided she would follow Adelaide’s lead.

Two decks below their own, there was a strong smell of rotting vegetation, which Adelaide told her came from the bilge. The soldiers’ wives were in a shared dormitory and Adelaide greeted them, explaining who she and Lucy were, and saying that they would be happy to offer assistance if any was required. The women looked doubtfully at Lucy, who was by far the youngest of the thirteen wives accompanying the 8th Hussars. Most were rough, sturdy women, with ruddy faces and cheap gowns; none looked a day under thirty.

‘What an exquisite shawl,’ Lucy commented to one woman, who was wearing a gaudy, paisley-patterned garment round her shoulders. ‘Are your beds comfortable? Ours is so narrow I think my husband will knock me to the floor if he turns in his sleep.’

‘Make sure you sleep by the wall so he’s the one that falls out,’ one suggested, and Lucy agreed that would be the sensible course. She asked about children left behind, about where the women normally lived, about their husbands’ names and duties, and she felt by the time she and Adelaide left that she had made a good first impression.

‘We will all be good friends after this adventure. I am sure of it,’ she called back.

That evening she and Charlie shared a table in the officers’ dining hall with the Cresswells. Lucy had changed into a blue and purple silk taffeta evening gown with smocked bodice, and dressed her own hair in the absence of any apparent ladies’ maids, but she noticed that Adelaide wore the same plain serge gown as earlier. Looking around, all the officers’ wives were in day dress; it seemed dinner was not a dressy occasion.

‘Why didn’t you warn me not to wear evening dress?’ she whispered to Charlie, feeling embarrassed.

He grinned. ‘I love to see you all dressed up. You are by far the most beautiful woman on the ship and I’m so proud to be with you.’

The food was plain cooking: soup, stew, pudding, with not even a fish course. The conversation was lively, though, with the men talking of war, and the belligerent stance of the Russian Tsar Nicholas I who dreamed of creating a huge empire in the East from the remains of the tottering Ottoman Empire.

‘Do you have children?’ Lucy asked Adelaide, and realised she had touched a raw nerve when tears sprang to Adelaide’s eyes, which she blinked away before replying.

‘We have a little girl called Martha, who is four, and a boy, Archie, who’s just three. I’m sorry …’ She closed her eyes briefly to regain control. ‘It was a wrench leaving them behind, although they are with my mother and will receive the best of care. I decided that Bill needed me more. I want to make sure he has a clean uniform and decent food as well as a woman’s comfort while he is out fighting for us.’

‘Well, of course,’ Lucy agreed. ‘All the same, I can imagine how difficult it must have been to leave your little darlings.’ Adelaide must be in her twenties to have such young children, she guessed; she looked older, her face tanned and lined by the sun.

After dinner, Lucy and Charlie strolled out on deck to watch as the Shooting Star pulled out of harbour then promptly came to a halt while they waited for the wind to change. She felt a thrill run through her: it was the first time she had left English soil. She felt so lucky to be there, with the man she loved. In their cabin, Charlie poured glasses of some rum he had brought along and they toasted the voyage: ‘We’re on our way!’ He raised his glass and she did the same. ‘This is where the adventure begins! And I am the happiest man alive that you are here by my side.’ He gazed at her and despite his words she could see the sadness in his eyes. She knew his loneliness after being cast off by his family still haunted him, although it had happened five years earlier. ‘If you had been unable to come, I swear I would have deserted from the army. I couldn’t bear to be without you now, Lucy.’

His words caught in his throat and Lucy knew how deeply they were felt. It was part of what made her love him so wholeheartedly: the sense that beneath his confident manner there was a vulnerable man who needed her in a way she had never been needed before.

‘I know, darling, and I couldn’t be without you either.’ She stroked his dear face with the tips of her fingers.

‘We are so lucky to have found each other,’ he breathed. ‘Before I met you, I was nothing, a hollow shell of a man. I had no family, just some friends who enjoy me larking around: “Good old Charlie, he’s always up for some fun.” But with you I can be myself and know you love me no matter what.’

‘I will always love you …’ she began to say but Charlie silenced her by covering her mouth with kisses so tender that her heart almost stopped. They fell onto the bed and while they made love she marvelled at his passion; she loved the way he lost himself completely in her, loved the amazing secret of married love into which she had now been initiated.

He fell asleep straight afterwards with his arm wrapped around her neck. She would have to wake him later because both were still half-clothed: her petticoats were twisted beneath her while he still wore his dress shirt, but she would let him rest awhile.

When she opened her eyes the next morning, Lucy could sense from a gentle rolling motion that the ship was on the move and she felt a quiver of excitement. That rolling became less gentle as the day progressed, and she had to press a hand to the corridor wall for support as she and Adelaide made their way to luncheon. Charlie’s day was spent trying to settle the horses, who neighed and whinnied, terrified of their enclosure in this rocking vessel, so Lucy and Adelaide strolled the deck gazing at the grey-green seas that surrounded them and took meals together. They went down to visit the soldiers’ wives again and Lucy was astonished to find some standing around in drawers and stays without a hint of modesty but she chatted as before, asking if their food was adequate and whether they saw more of their husbands than she was seeing of hers. She joked that Captain Harvington seemed to care more about the horses than his new wife, but in fact she loved the caring way he spoke of those magnificent creatures, particularly his own horse, Merlin, and his determination that he would do all he could to see they survived the journey unscathed.

On the second day, as they entered the Bay of Biscay, the sea became choppy. Loose objects fell from shelves and a little flower vase of Lucy’s was smashed on the cabin floor, startling her. After dressing, she made her way to Adelaide’s cabin to find her friend vomiting into a bedpan, her face bleached of colour and eyes sunken in their sockets. Lucy gave her a handkerchief to wipe her mouth, then went to find a steward who would empty the bedpan and bring a fresh pitcher of water.

‘All the other ladies are sick as well, Ma’am,’ the steward told her. ‘You must have a strong constitution.’

Sure enough, she heard retching sounds from Mrs Duberly’s cabin, although the quartermaster’s wife came to dinner that evening and remarked to Lucy she thought it a poor show that Adelaide didn’t make the effort to join them.

In fact, for the next three days poor Adelaide couldn’t keep down more than a few sips of water and Lucy was concerned for her. There was no doctor on board but the steward found a supply of Tarrant’s Seltzer so Lucy fed Adelaide teaspoonfuls of it, trying to keep her spirits up by telling her that the rough weather must pass soon; everyone said it must. She herself remained miraculously immune to the seasickness, and was able to go down to the soldiers’ wives and dispense fizzing glasses of seltzer to them too. It was good to feel useful, and as Adelaide began to recover Lucy sat and read to her, growing fonder by the day of her sweet nature. She was the kind of woman who would never hear bad of another; a woman whose outlook was sunny even while she was feeling so ill.

On their fourth night at sea there was a horrendous storm. Waves crashed against the side of the ship, lightning crackled and lit up the entire sky, and the frightened whinnying of horses filled the air. Lucy couldn’t sleep a wink but sat petrified by their porthole, watching the violence of the storm outside, while Charlie spent the night down below, sponging the horses’ nostrils with vinegar in an attempt to calm them. At one stage there was a terrible cracking sound, like an explosion, and for a moment Lucy feared they had been attacked by the Russians. She wrapped the silk bedspread around her, rubbing it against her lip for comfort as she used to do as a child when she fled to her mother’s bed after a nightmare. If only Charlie would come soon. There were a few terrifying hours before the worst was over, but as soon as dawn broke with a pale pink shimmer, the storm passed and the ship stopped rolling.

Charlie returned with some awful news: ‘The mizzen top and the main top mast broke at the height of the storm and crushed a man’s leg as they fell to deck.’

She was shocked. ‘Will he be all right?’

He shook his head. ‘He’ll lose the leg, for sure. Two of our horses – Moondance and Greystokes – perished. I couldn’t settle them and the poor creatures raved themselves to death.’

‘Is Merlin all right?’

‘Yes, thank goodness. Biscay is always rough but this is the worst storm I’ve experienced and it followed us right down the coast of Spain and Portugal. At least we’re through it now.’

Spain and Portugal: names Lucy had previously only seen on her father’s globe. She knew that Columbus had sailed from Portugal and imagined it as being very exotic. ‘Will they be able to mend the ship?’

‘Yes, the carpenters are hard at work.’ He noticed Lucy’s anxious expression and pulled her in for a hug. ‘Everything will be fine, my love. And you have been extraordinarily strong in the face of adversity. I knew you would be.’

She was thrilled with the compliment. ‘You must be exhausted. Why not lie down and rest awhile?’

‘I think I will. Come lie with me.’

Lucy held him close until he fell asleep and then she rose, dressed quietly and slipped up on deck to gaze out at the millpond sea glittering in the early morning light. The ship was close enough to shore for land to be visible and she shivered at the thought they were getting ever-nearer to the mysterious Turkish lands.

‘What is that huge black rock?’ she asked a passing sailor, and he told her ‘The Rock of Gibraltar, Ma’am.’

She stood watching as they pulled up beneath it then came to a halt, becalmed in the Straits. The Rock’s sheer slopes towered high above the ship’s main mast, like an ominous shadow against the sky.

On the 8th May, the Shooting Star docked at Valletta in Malta and all were allowed to go ashore. Adelaide had fully recovered and she and Lucy, along with Charlie and Bill, descended the gangway to the dock, the ladies sheltering beneath parasols from the heat of the sun. ‘What larks!’ Lucy cried, scarcely able to contain her excitement as she set foot on foreign soil. Locals flocked around trying to sell them hand-coloured cards, china knick-knacks and bonnets made out of scratchy straw. They sat in a café near the dock sipping tea and watching fishermen drag boxes of fresh fish up the slope. One man was pounding a freshly caught octopus against a rock – to tenderise its meat, Charlie said – and Lucy flinched at the blows. They dined well in a local hostelry, with fresh fish in a cream sauce, tender lamb chops, and delicate little custard puddings. A fiddler played in the corner and once they had eaten Charlie persuaded the waiters to clear some tables so there was room for dancing, which he led in high-kicking style, pulling Lucy up to join him in a lively polka. Bottles of jewel-coloured liqueurs were produced, made from fruits Lucy had never heard of: prickly pear, pomegranate and carob. The ladies tried delicate sips but found them over-strong.

They were joined by Major Dodds, who challenged Charlie to drink a shot of each spirit behind the bar and said he would do the same. Their aim was explained to the bartender who lined up glasses in a row, which they supped in carnival style. A game of cribbage was initiated and Lucy could tell from Charlie’s excited whoops that he was winning.

‘They call him Lucky Charlie,’ Adelaide told her. ‘No matter what the game, he seems to have a knack with cards.’

Lucy hadn’t known that her husband liked gambling. Dorothea was very disapproving of gamblers and would have considered it a black mark against him, but Adelaide didn’t seem to see any harm in it. Lucy was learning more about her husband all the time. It wasn’t just his funny dancing style, and the fact that he was said to be lucky; she had never realised how popular he was with his fellows and it was heart-warming to watch. She had no regrets about coming away with him; she just wished it had been possible for her older sister to share her joy.

The next day she wrote to her father. Charlie had asked her not to write before they set sail in case Dorothea made one last attempt to stop them, but she missed her papa and now they were on their way she could see no harm in it.

‘The soldiers’ and officers’ wives are one happy family,’ she wrote, ‘linked by a warm camaraderie and eagerness to explore our new surroundings. We are enjoying the foreign aspects of Malta, with its fragrant flowers trailing up the walls of houses and twining round balconies, the dark-eyed children who follow us in the street, and the uncannily bright blue of sea and sky sparkling in sunlight.’ She sucked the end of her pen then continued: ‘I hope that you are in good health, Papa, and that your back is not troubling you. I will write again when I can, but do not worry if you don’t hear for a while as we may not be able to post our letters when in the field.’ She signed the letter ‘Your loving daughter’. She didn’t ask after Dorothea, still cross whenever she thought of her meddling. Her sister had believed she was behaving as a mother to Lucy, but in fact their real mother, the irrepressibly gay woman who had died when Lucy was thirteen, would have been wildly enthusiastic about this trip. Lucy imagined her crying, ‘My darling, what fun! Be sure to write and describe all the details. And bring me back a Russkie’s helmet!’

Before they set sail from Malta, Lucy was astonished to hear that five out of the thirteen Hussars’ wives had asked to be sent home to England. The rigours of the voyage had been too much for them and they did not want to continue further. She remonstrated with one woman.

‘Won’t you stay to support our brave troops? Think how much comfort it would bring your husband to have you with him. Please say you will reconsider.’

The woman shook her head, a little shamefaced but determined. ‘It’s too hard on the ship. You have a nice cabin but we’ve been stuck in that awful dormitory listening to the sounds of each other vomiting, and breathing smells the like of which I hope never to come across again, while being tossed around in an old wooden bucket.’

‘But the war will not last long. With the British and French joining the Ottomans, it is three armies against one. The Russians can’t possibly hold out.’

‘All the same, I can’t take the risk, Ma’am. I have four children. I have to get myself back to them in one piece.’

Lucy bit her lip, thinking of the sobbing women in Plymouth Dock who would have given anything to be there. It was incomprehensible to her that someone could decide to leave just as the adventure was commencing. Granted, the voyage had been unpleasant but now they were all together, exploring the island by day and throwing impromptu parties every night, she was filled with excitement at the prospect of the coming months. She was doing her duty to her country and to her new husband; who would have thought it would turn out to be such fun?