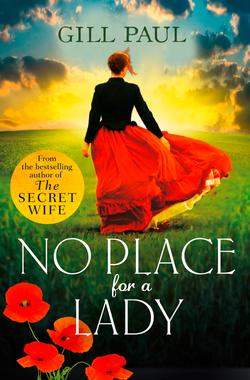

Читать книгу No Place For A Lady: A sweeping wartime romance full of courage and passion - Gill Paul, Gill Paul - Страница 21

Chapter Ten

ОглавлениеA reporter for The Times newspaper, a plain-speaking Irishman called W.H. Russell, was living close to the troops in Varna and he sent back dispatches that described conditions as he saw them. Dorothea followed the news stories with mounting anxiety. Russell informed the British public that over a thousand men had died from cholera, diarrhoea and dysentery before a single shot was fired and that medical facilities were scandalously inadequate. Instantly there was an outcry, with government ministers scurrying around looking for someone to blame and worthy gentlemen writing to the papers asking what could be done.

On the 9th October, six months since Lucy had embarked, Mr Russell’s story in The Times told of the army’s ‘glorious victory’ at the Battle of Alma but said there were few surgeons and no hospitals so those requiring anything more than a simple battlefield dressing must sail south to Constantinople aboard what he described as ‘fetid ships’. He wrote there was insufficient linen for bandages and that conditions were those of ‘humane barbarity’, with some injured men waiting forty-eight hours or more for treatment. Soldiers’ wives who had accompanied the troops were helping to look after the less seriously wounded, but officers’ wives had been encouraged to stay at Varna or Constantinople. Dorothea had no idea where Lucy might be; only that she was far from home and in mortal danger.

Her fear increased as the autumn air turned chilly and she thought of Lucy out there with only her summer wardrobe and some evening gowns. Should she send some warmer clothes, perhaps a coat? Or would they get lost along the way? It was dark when she left the hospital each evening, underlining the changing of the season. Most of her time was spent at work or at home with her father, but she sometimes went with her friend Emily Goodland, the sister of William, to hear concerts given by the Royal Philharmonic Society at Exeter Hall or to view the paintings in the Royal Academy of Art in Trafalgar Square. She often discussed her worries about Lucy with her friend. One chilly October evening Emily mentioned she had heard that a Miss Florence Nightingale, who was superintendent at the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in Harley Street, had been asked by the government to take a small party of nurses out to the Turkish lands to see what could be done to relieve the suffering of the wounded.

‘Perhaps you could ask one of Miss Nightingale’s party to look out for Lucy?’ she suggested. ‘They could pass on a message if they see her.’

Dorothea’s heart leapt. ‘I am a great admirer of Miss Nightingale’s. Do you know which nurses she will take?’

‘I’m not sure,’ Emily replied, ‘but I did hear that she wants mature women with nursing experience.’ She looked at Dorothea with a peculiar expression. ‘Why? You wouldn’t consider volunteering, would you?’

Instantly, Dorothea felt she should, and not just so that she could look for Lucy. Something else tugged at her heart. This was her chance to see a little more of the world and make a difference to it. She had no illusions about the awful injuries she might have to treat in a battlefield hospital; she had dressed some terrible wounds sustained by the men building the new railways, who got crushed by hefty metal rails, had limbs mangled in unfamiliar machinery and were severely burned when boilers unexpectedly exploded. She knew she could cope with virtually anything after that. She could be useful in Crimea; she knew she could.

‘Yes, I would. Do you know how one should apply to be amongst the party?’

‘I don’t know any more than I told you. I assumed you would feel your ties at home would prevent you from making such a trip.’

‘On the contrary, I should be most interested in finding out about it.’

She sensed Emily disapproved but could not work out why. Maybe it was because her friend didn’t entirely approve of her working in a hospital. They could be dangerous places, and many of the nurses she worked alongside were rough women who drank on duty and treated patients with disdain. Most lady volunteers didn’t so much as soil their begloved hands, but Dorothea loved to learn about medicine and often shocked Emily with her tales of procedures she had carried out.

Next morning, she rose early and skipped breakfast in order to make enquiries about the party of nurses going to the Crimea. Her matron, Miss Alcock, found out on her behalf that the final interviews were taking place that very morning at 49 Belgrave Square, the house of the Minister for War, Sidney Herbert, so Dorothea rushed straight there.

A line of chairs was set out in the grand entrance hall and she was invited to take a seat. No one else was there when she arrived but as she waited, an Irishwoman who looked to be in her fifties or sixties came in and sat with a groan, one hand clutching her lower back. They greeted each other but did not have a chance to make conversation before Dorothea was called in to an adjacent room. At a long table sat four women, who were introduced as Mrs Herbert (wife of the minister), Mrs Bracebridge and Miss Stanley (both friends of Miss Nightingale) and Miss Parthenope Nightingale (Florence’s sister).

‘What experience could you bring to our party?’ Mrs Bracebridge asked.

Dorothea explained about her work, and told them that she knew all about wound dressing and care of fevers.

‘How did you come to learn of such things?’ She peered at Dorothea as if reassessing her.

Dorothea coloured, then said that her matron, Miss Alcock, had encouraged her to learn.

It seemed Mrs Bracebridge knew Miss Alcock and they conversed for a while about that decent soul. Her manner warmed somewhat and Dorothea gained confidence.

‘Before I started work in the hospital, I spent years nursing my mother through breast cancer and other complaints that arose from her condition.’ Dorothea hurried on so as not to dwell on this. ‘The experience gave me a keen insight into care of the dying.’

‘What age are you?’ Miss Stanley asked in a friendly tone. Dorothea told her and she wrote it on a sheet of paper. ‘Are you married?’ she continued, and when Dorothea said she was not, she asked, ‘Do you hope to marry?’

‘No, I do not,’ Dorothea answered truthfully. Any such hopes she might once have harboured had long been extinguished.

‘Good,’ Miss Stanley nodded. ‘Women who intend to find a husband among the wounded soldiers are no use to us. Worse than useless, in fact. There must be no fraternising of any sort with the patients.’

‘I understand. Of course not.’

‘How many years have you been a nurse?’ Miss Nightingale asked, and Dorothea said she’d spent six years nursing her mother, then another five working at the Pimlico hospital.

‘What is your religion?’

‘Church of England.’

‘Who will care for your father if you are chosen to come on our expedition?’ Mrs Herbert took over. ‘Do you have siblings?’

‘My father has servants to care for his physical needs, and is quite content with the company of his butler. I’m sure he will manage perfectly well without me.’ Dorothea paused. ‘My only sibling, my sister Lucy, is already out East; she accompanied her officer husband. I am concerned because we do not hear from her regularly and she was in Varna during the cholera outbreak. Perhaps I would be able to reunite with her at the same time as helping …’ Her voice tailed off as she saw the looks the women were exchanging.

Mrs Bracebridge pursed her lips. ‘We are not here to help families be reunited. The women we choose must be totally dedicated to nursing injured soldiers and will probably never set foot outside the hospital … I’m afraid you are not suitable.’

Dorothea panicked: ‘I only meant that perhaps while I am working out there I might hear word of my sister. I certainly would not shirk my ward duties to look for her. I have never missed a day since I started volunteering in Pimlico. You can ask Miss Alcock; I’m sure she will tell you I am utterly dedicated.’

‘All the same, your mind would be on family matters. I’m afraid we must say no, Miss Gray. Now, if you don’t mind we have other candidates waiting to be seen.’

‘Please reconsider,’ Dorothea begged, struggling to stop herself bursting into tears. ‘I should never have mentioned my sister. Of course it is unlikely I would see her amongst all the thousands of people out there. I want to nurse, to relieve suffering and to serve my country.’

Mrs Bracebridge was immovable. ‘Send in the next candidate please, Miss Stanley.’

Miss Stanley, the youngest of the four interviewers, stood and moved to the door, opening it and holding it for Dorothea to pass.

As Dorothea rose, she gazed from one face to the next, desperately looking for a sign of sympathy, a weakening of resolve, but their minds were made up. She wasn’t going.

She was distraught during the carriage ride along Birdcage Walk to the hospital. The trees had turned golden brown almost overnight, and falling leaves swirled high in the air carried on fierce gusts of wind. If only she hadn’t mentioned Lucy. What a fool she was.

She confided in Miss Alcock, who sent a personal note to Mrs Bracebridge arguing Dorothea’s case and her hopes were raised once more. But the reply came back promptly that they had received 617 applications, many of them from highly qualified women, and had already chosen the nurses they were taking.

Dorothea wept as she read in The Times of Florence Nightingale’s band of thirty-eight women setting off to Paris on the 23rd October then overland to Marseilles and on by ship to Scutari. Her one chance of leading a life of some value was lost. Instead it was back to reading to patients, dressing their wounds and helping them to eat their meals in the same old London wards, then the stultifying atmosphere of evenings spent with her father in a house that was too big for them, where her footsteps echoed and everything reminded her of the absence of Lucy and the emptiness in her heart.