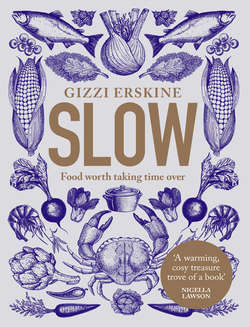

Читать книгу Slow: Food Worth Taking Time Over - Gizzi Erskine - Страница 20

ОглавлениеStews & Pies

Braising meat must be one of the more satisfying processes in the kitchen, often taking the more unloved cuts and investing time and care until they yield beautiful, tender delicious meat. Whichever meat you choose, the qualities you are looking for are plenty of fat, sinew and dense, collagen-rich connective tissue. In short, the very things that make the meat unsuitable for fast cooking, but ideal for a slow braise.

When it comes to beef, shin, cheek, featherblade and oxtail are the perfect cuts for braising. Many people favour chuck steak for stewing, but personally I would recommend the others as they are far more flavourful and cook to a perfect wobble, which melts away the second a fork sinks into them. All these cuts come from the parts of the cow that do the most work, which means the muscles are more exercised, the connective tissues stronger, and therefore the meat tougher. The stronger the muscle, the more collagen it contains. Given the right conditions (cooked in stock, wine or beer with stewing vegetables and herbs, slowly, at a low heat) these tissues break down and soften, resulting in beautifully moist, falling apart meat. The same principles apply to lamb; the shoulder, shank or neck respond well to slow braising, and pork, for which shoulder or cheek are the obvious choices – although in fact you can braise any part of a pig or a sheep and still get decent results.

Having leftover stew in the fridge is never a problem. It’s a well known fact that stews and ragus taste better the day after they are cooked, as the flavours have developed and intensified. Of course they are a treat eaten as they are, but why not add an extra dimension to a stew’s potential with the always-welcome addition of pastry – thus creating a pie? The following recipes create perfect pie fillings: my Steak & Kidney Pudding (see here), Ox Cheeks Stewed with Wine & Beer (see here), Pork & Apple ‘Stroganoff’ (see here), Braised Chicken with Shallots, Orange Wine & Brandy – though you need to take the chicken off the bone (see here), Braised Lamb Mince (see here), the stew from my Lamb Hotpot (see here) – and, of course, my Chicken, Buttermilk & Wild Garlic Pie (see here) recipe is a classic. I probably wouldn’t use my Oxtail Stew as I think this is one occasion you’d lose something by not eating the meat from the bone. Please don’t judge me but one of my guilty pleasures is sucking any remaining marrow from the oxtail bones.

Pretty much any stew can be easily transformed into a pie if you follow a few simple guidelines. First you need to ensure that you have a nice thick stew as too much liquid will make your pastry soggy, so you may need to reduce your stew a little. On the other hand, there’s nothing worse than a dry pie, so if the sauce looks a little thick, you may want to loosen it with a little water or stock.

It’s essential to chill your pie filling before it makes contact with the pastry as the key to achieving crisp pastry is keeping it cold. Depending on your preference, you can opt for either shortcrust or puff pastry. Shortcrust works best if you want the entire filling encased in pastry, and puff is better if you just want a pastry lid on top to make a pot pie. Although it’s perhaps an easier option, an American pot pie is not strictly a pie in my view. Call me a traditionalist, but I want pastry top and bottom!

To achieve a lovely glossy finish, always glaze your pastry with beaten egg. A good rule of thumb for cooking a shortcrust pie is to preheat the oven to 190˚C/170˚C fan/gas mark 5 and to cook the pie for 35–40 minutes until the pastry is golden brown and cooked through. Puff pastry requires a hotter, shorter cooking time, so I suggest 220˚C/200˚C fan/gas mark 7 for about 30 minutes.